Disability Studies Quarterly Winter 2003, Volume 23, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Mice and Men John Steinbeck

Of Mice and Men John Steinbeck Discussion & Activities Guide Parental warning: This story contains profanity and mature themes. Parents and teachers should preview before determining if this is an appropriate book for their students. Discuss the following elements with your student, as a whole class, or pair students up for discussion and then present ideas back to whole group/class. John Steinbeck Research Steinbeck’s life and background. In many literary works the setting (where the story takes place) is different from the context (when & where the writer lived), but in Steinbeck’s stories the setting is when and where he lived. Steinbeck was born in 1902, in Salinas, California, which is also the setting for Of Mice and Men. As a teenager, Steinbeck spent summers working as a hired hand on ranches, and many of his characters are based on people he met. Discuss how a writer is reflected in his or her writing. Why is it important to understand who a writer is when reading his/her work? Why do you need to be aware of bias and agenda? Discuss how the story Of Mice and Men specifically reflects Steinbeck. Encourage students to be as specific as possible, with passages from the text. Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962 Watch his full speech at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7SKEODtaQUU Steinbeck declared, “…. the writer is delegated to declare and to celebrate man’s proven capacity for greatness of heart and spirit—for gallantry in defeat, for courage, compassion and love. In the endless war against weakness and despair, these are the bright rally flags of hope and of emulation. -

Of Mice and Men

P RESTWICK HOUSE ActivityActivity PackPack OF MICE AND MEN BY JO HN STEINBECK Copyright © 2001 by Prestwick House, Inc., P.O. Box 658, Clayton, DE 19938. 1-800-932-4593. www.prestwickhouse.com Permission to use this unit for classroom use is extended to purchaser for his or her personal use. This material, in whole or part, may not be copied for resale. Revised August 2009. Item No. 200219 Edited by Paul Moliken Student’s Page Of Mice and Men Name: ________________________________ Date:_________________ Section 1 Description Objectives: Visualizing a scene Recognizing the use of concrete detail in descriptive writing Activity Steinbeck opens the novel with a description of a deep, green pool. 1. List all the concrete details that are included in the description. For instance, willow and sycamores are described in detail. Steinbeck mentions the wildlife around the pool “A stilted heron labored up into the air and pounded down river”; and “A water snake slipped along the pool, its head held up like a little periscope.” 2. List some ideas that come to mind as you read Steinbeck’s description. S - 9 Reproducible Student Worksheet Student’s Page Of Mice and Men Name: ________________________________ Date:_________________ Section 1 Characterization Objectives: Recognizing how character traits are revealed Inferring meaning about a character by contrasting him or her with other characters Activity George and Lennie are frequently presented as opposites. Use the chart on the next page to contrast their physical and mental characteristics, personalities, and attitudes. S - 19 Reproducible Student Worksheet Student’s Page Of Mice and Men Name: ________________________________ Date:_________________ Section 2 Narrative Technique Objective: Interpreting the impact of the narrative device of a choral character Activity In Greek drama, a group of characters, or chorus, would comment on the action of the play and provide any background information the audience needed. -

Floyd's Susannah

Baltimore Concert Opera presents: Floyd’s Susannah Who is Carlisle Floyd? The Gist of the Story: Setting: New Hope Valley, Tennessee in the mid 20th century; loosely inspired by the Apocryphal tale of Susannah and the Elders WHO? Set in the 1950s in the backwoods of Tennessee Composer and Librettist: hill country, the opera centers on 18-year-old Susannah, who faces hostility from women in Carlisle Floyd her church community for her beauty and the (born June 11, 1926) attention it attracts from their husbands. As she innocently bathes in a nearby creek one day, the WHAT? church elders spy on Susannah, and their own lustful impulses drive them to accuse her of sin Floyd called this operatic and seduction. Among these hypocrites is the creation a ‘musical drama,’ newly-arrived Reverend Olin Blitch, whose focusing on both music and own inner darkness leads to heart-wrenching Born in South Carolina to a piano teacher and a text to tell the story. tragedy for Susannah. Dealing with the Methodist minister, Carlisle Floyd developed an dramatic themes of jealousy, gossip, and interest in music early on. Studying creative ‘group-think’ -- and filled with soaring folk- writing, piano and then coming to composition, WHEN? inspired melodies -- this opera has been a he found himself teaching at Florida State Premiered on favorite of opera-goers for many years. University in the mid 1950s. Always one to February 24, 1955 The Characters write both the music and texts for his operas, he (62 years prior to our believes that this process gives him greater REV. -

Nationalsteinbeckcenter News Issue 70 | December 2017

NATIONALSTEINBECKCENTER NEWS ISSUE 70 | DECEMBER 2017 Drawing of Carol Henning Steinbeck, John’s frst wife Notes From the Director Susan Shillinglaw The National Steinbeck Center has enjoyed a busy, productive It may be well to consider Steinbeck’s role in each of these NSC fall: a successful National Endowment for the Arts Big Read of programs—all of which can be linked to his fertile imagination Claudia Rankine’s Citizen; a delightful staged reading of Over the and expansive, restless curiosity. John Steinbeck was a reader River and Through the Woods in the museum gallery as part of of comics, noting that “Comic books might be the real literature our Performing Arts Series, produced by The Listening Place; a of our time.” He was passionate about theater—Of Mice and robust dinner at the Corral de Tierra Country Men, written in 1937, was a play/novelette, an experiment in Club, the 12th annual Valley of the World writing a novel that could also be performed exactly as written fundraiser celebrating agricultural on stage (he would go on to write two more play/novelettes). leaders in the Salinas Valley; and the He wrote often and thoughtfully about American’s racial legacy, upcoming 4th annual Salinas Valley and Rankine’s hybrid text--part poetry, part nonfiction, part Comic Con, co-sponsored by the Salinas image, part video links—would no doubt intrigue a writer who Public Library and held at Hartnell insisted that every work of prose he wrote was an experiment: College in December—“We “I like experiments. They keep the thing alive,” he wrote in are Not Alone.” All are covered 1936. -

MICE and MEN by John Steinbeck Directed by Edward Stern

2006—2007 SEASON OF MICE AND MEN By John Steinbeck Directed by Edward Stern CONTENTS 2 The 411 3 A/S/L 4 FYI/HTH 6 B4U 8 F2F/RBTL 10 IRL 12 SWDYT? STUDY GUIDES ARE SUPPORTED BY A GENEROUS GRANT FROM CITIGROUP MISSOURI ARTS COUNCIL MIHYAP: TOP TEN WAYS TO STAY CONNECTED AT THE REP At The Rep, we know that life moves fast— 10. TBA Ushers will seat your school or class as a group, okay, really fast. so even if you are dying to mingle with the group from the But we also know all girls school that just walked in the door, stick with your that some things friends until you have been shown your section in the are worth slowing down for. We believe that live theatre is theatre. one of those pit stops worth making and are excited that 9. SITD The house lights will dim immediately before the you are going to stop by for a show. To help you get the performance begins and then go dark. Fight off that oh-so- most bang for your buck, we have put together immature urge to whisper, giggle like a grade schooler, or WU? @ THE REP—an IM guide that will give you yell at this time and during any other blackouts in the show. everything you need to know to get at the top of your 8. SED Before the performance begins, turn off all cell theatergoing game—fast. You’ll find character descriptions phones, pagers, beepers and watch alarms. If you need to (A/S/L), a plot summary (FYI), biographical information text, talk, or dial back during intermission, please make sure on the playwright (F2F), historical context (B4U), and to click off before the show resumes. -

SOME AMERICAN OPERAS/COMPOSERS October 2014

SOME AMERICAN OPERAS/COMPOSERS October 2014 Mark Adamo-- Little Women, Lysistrata John Adams—Nixon in China, Death of Klinghoffer, Doctor Atomic Dominick Argento—Postcard From Morocco, The Aspern Papers William Balcom—A View From the Bridge, McTeague Samuel Barber—Antony and Cleopatra, Vanessa Leonard Bernstein— A Quiet Place, Trouble in Tahiti Mark Blitzstein—Regina, Sacco and Venzetti, The Cradle Will Rock David Carlson—Anna Karenina Aaron Copland—The Tender Land John Corigliano—The Ghosts of Versailles Walter Damrosch—Cyrano, The Scarlet Letter Carlisle Floyd—Susannah, Of Mice and Men, Willie Stark, Cold Sassy Tree Lukas Foss—Introductions and Goodbyes George Gershwin—Porgy and Bess Philip Glass—Satyagraha, The Voyage, Einstein on the Beach, Akhnaten Ricky Ian Gordon—Grapes of Wrath Louis Gruenberg—The Emperor Jones Howard Hanson—Merry Mount John Harbison—The Great Gatsby, Winter’s Tale Jake Heggie—Moby Dick, Dead Man Walking Bernard Hermann—Wuthering Heights Jennifer Higdon—Cold Mountain (World Premiere, Santa Fe Opera, 2015) Scott Joplin—Treemonisha Gian Carlo Menotti—The Consul, The Telephone, Amahl and the Night Visitors Douglas Moore—Ballad of Baby Doe, The Devil and Daniel Webster, Carrie Nation Stephen Paulus—The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Woodlanders Tobias Picker—An American Tragedy, Emmeline, Therese Racquin Andre Previn—A Streetcar Named Desire Ned Rorem—Our Town Deems Taylor—Peter Ibbetson Terry Teachout—The Letter Virgil Thompson—Four Saints in Three Acts, The Mother of Us All Stewart Wallace—Harvey Milk Kurt Weill—Street Scene, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny . -

Home Runs in the Opera House — Gordon Hawkins by Susan Dormady

10 Home Runs in the Opera House — Gordon Hawkins by Susan Dormady After winning the Pavarotti Competition in 1992, Gordon Hawkins faced a difficult decision: break his contract at the Met to work with Pavarotti in two operas, or stay at the Met, where he was on his way to becoming a contract singer. Looking back, Mr. Hawkins has no regrets about the decision he made, which led to a successful international career. Find out how singing in Europe helped shape him as an artist. Discover his process for delving into the character of an opera, and read how having a big voice was both a blessing and a curse. Gordon Hawkins as George in Houston Grand Opera’s production of Of Mice and Men. photo by George Hixson 10 Classical Singer / March 2006 11 Gordon Hawkins “Music and baseball were my two passions. But when I went to Maryland at 17, I tore my rotator cuff, and though I recovered enough to play—I could even still pitch—the day after a game I could hardly lift my arm. Eventually, I stopped playing.” It was part of and said, “Have a wonderful life!” Then I the fabric of my walked up to the top of the hill to the Music childhood. I didn’t Department. [Laughs.] Even though I quit my see it as unusual that formal study of math, what makes me good there were seven as a singer has to do with my mathematical photo by Michael Melcer people in the house, aptitude, combined with my athletic aptitude. -

The Function of Female Characters in . Steinbeck's Fiction: the Portrait of Curley's Wife in of Mice and Men

UDK 821.111(73).09 Steinbeck J. THE FUNCTION OF FEMALE CHARACTERS IN . STEINBECK'S FICTION: THE PORTRAIT OF CURLEY'S WIFE IN OF MICE AND MEN Danica Cerce "Preferably a writer should die at about 28. Then he has a chance of being discovered. If he lives much longer he can only be revalued. I prefer discovery." So quipped the Nobel prize-winning American novelist John Steinbeck (1902-1968) to the British journalist Herbert Kretzmer in 1965. 1 Steinbeck died at the age of 66, however, as many critics have noted, there is still a lot about him to be discovered. It must be borne in mind that Steinbeck's reputation as the impersonal, objective reporter of striking farm workers and dispossessed migrants, or as the escapist popularizer of primitive folk, has needlessly obscured his intellectual background, imaginative power and artistic methods. Of course, to think of Steinbeck simply as a naive realist in inspiration and a straightforward journalist while his achievement as a writer extends well beyond the modes and methods of traditional realism or documentary presentation is to disregard the complexities of his art? For this reason, new readings and modern critical approaches constantly shed light on new sources of value in Steinbeck's work. Many book reviewers and academic critics became antagonistic toward the writer when he grew tired of being the chronicler of the Depression and went further afield to find new roots, different sources and different forms for his fiction. As their expectations were based entirely on his greatest novel, The Grapes of Wrath (1939), winner of the 1940 Pulitzer Prize, cornerstone of his 1962 Nobel prize award, and one of the most enduring works of fiction by any American author, Steinbeck's subsequent work during and after World War II understandably came as a startling shock. -

John Steinbeck

John Steinbeck Authors and Artists for Young Adults, 1994 Updated: July 19, 2004 Born: February 27, 1902 in Salinas, California, United States Died: December 20, 1968 in New York, New York, United States Other Names: Steinbeck, John Ernst, Jr.; Glasscock, Amnesia Nationality: American Occupation: Writer Writer. Had been variously employed as a hod carrier, fruit picker, ranch hand, apprentice painter, laboratory assistant, caretaker, surveyor, and reporter. Special writer for the United States Army during World War II. Foreign correspondent in North Africa and Italy for New York Herald Tribune, 1943; correspondent in Vietnam for Newsday, 1966-67. General Literature Gold Medal, Commonwealth Club of California, 1936, for Tortilla Flat, 1937, for novel Of Mice and Men, and 1940, for The Grapes of Wrath; New York Drama Critics Circle Award, 1938, for play Of Mice and Men; Academy Award nomination for best original story, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, 1944, for "Lifeboat," and 1945, for "A Medal for Benny"; Nobel Prize for literature, 1962; Paperback of the Year Award, Marketing Bestsellers, 1964, for Travels with Charley: In Search of America. Addresses: Contact: McIntosh & Otis, Inc., 310 Madison Ave., New York, NY 10017. "I hold that a writer who does not passionately believe in the perfectibility of man has no dedication nor any membership in literature." With this declaration, John Steinbeck accepted the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962, becoming only the fifth American to receive one of the most prestigious awards in writing. In announcing the award, Nobel committee chair Anders Osterling, quoted in the Dictionary of Literary Biography Documentary Series, described Steinbeck as "an independent expounder of the truth with an unbiased instinct for what is genuinely American, be it good or ill." This was a reputation the author had earned in a long and distinguished career that produced some of the twentieth century's most acclaimed and popular novels. -

Rediscovering Me and Juliet and Pipe Dream , the Forgotten Musicals of Rodgers and Hammerstein

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: “WHO EXPECTS A MIRACLE TO HAPPEN EVERY DAY?”: REDISCOVERING ME AND JULIET AND PIPE DREAM , THE FORGOTTEN MUSICALS OF RODGERS AND HAMMERSTEIN Bradley Clayton Mariska, Master of Arts, 2004 Thesis directed by: Assistant Professor Jennifer DeLapp Department of Musicology Me and Juliet (1953) and Pipe Dream (1955) diverged considerably from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s influential and commercially successful 1940s musical plays. Me and Juliet was the team’s first musical comedy and had an original book by Hammerstein. Pipe Dream was based on a John Steinbeck novel and featured bums and prostitutes. This paper documents the history of Me and Juliet and Pipe Dream , using correspondence, early drafts of scripts, interviews with cast members, and secondary sources. I analyze the effectiveness of plot, music, and lyrics, while considering factors in each show’s production that may have led to their respective failures. To better understand reception, emphasis is placed upon each show’s relationship to the political and cultural landscape of 1950s America. Re-examining these musicals helps document the complete history of the Rodgers and Hammerstein collaboration and provides valuable insights regarding the duo’s social values and personal philosophies of musical theatre. “WHO EXPECTS A MIRACLE TO HAPPEN EVERY DAY?”: REDISCOVERING ME AND JULIET AND PIPE DREAM , THE FORGOTTEN MUSICALS OF RODGERS AND HAMMERSTEIN by Bradley Clayton Mariska Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts 2004 Advisory Committee: Professor Jennifer DeLapp, Chair Professor Barbara Haggh-Huglo Professor Richard King © Copyright by Bradley Clayton Mariska 2004 To Grandma Bonnie, for The Sound of Music To my parents, for Joseph ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many individuals who have helped in the completion of this document. -

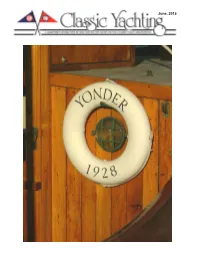

PNW Fleet and CAN Fleet Report – Let Boating Begin! by Ken Meyer, PNW Fleet Director and CYA Vice Commodore

June, 2015 PNW Fleet and CAN Fleet Report – Let Boating Begin! by Ken Meyer, PNW Fleet Director and CYA Vice Commodore Spring brings tasks and celebrations. When all of the painting, varnishing, changing of the zincs, and mechanical systems maintenance is complete, it is time for festivities. This is the case for most boating organizations and ours included. I would like to focus on two instances of participation by our CYA members. Opening Day in Seattle dates back to the late 1800s and has been hosted in recent years by the Seattle Yacht Club. In 1978 Sally Laura of the SYC invited some classics to join the parade. Those 10 or so boats became the founders of the PNW Fleet of the CYA. Today, the event is more than a week long and a year in planning that involves more than 300 people serving on many individual Seattle Yacht Club committees. The CYA boats participating are given priority dock space for their stay at the SYC docks and a short term membership card allowing them to use the bar, restaurant, and other club facilities. We join more than 300 other visiting yacht club boats in festivities at the dock and in the parade and review of boats. The Commodore of the PNW fleet is invited to and attends the flag raising ceremonies on Saturday morning (always the first Saturday in May). This year our PNW Fleet Commodore, Bob Wheeler, was one of the 40 Commodores and representatives of local yacht clubs standing in dress blues and whites during the raising of the flags of each boating organization and the flags of the USA and Canada. -

John Steinbeck

Year 9 English w/c 1st June ‘Of Mice & Men’ Week 1: Context Research This term we will be studying the novella Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck. The book is divided into six chapters, and for each chapter you will be completing a variety of activities to develop your understanding of the text. Before we start looking at the novel itself, it will be useful to explore some of the background of John Steinbeck, his work and its historical and social context. Task 1: read the information below and highlight the key information. Biographical Context: John Steinbeck (1902–1968) Who Was John Steinbeck? John Steinbeck was a Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-winning American novelist and the author of Of Mice and Men, The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden. Steinbeck dropped out of college and worked as a manual labourer before achieving success as a writer. His works often dealt with social and economic issues. His 1939 novel, The Grapes of Wrath, about the migration of a family from the Oklahoma Dust Bowl to California, won a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Steinbeck served as a war correspondent during World War II, and he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962. Early Life and Education John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. was born on February 27, 1902, in Salinas, California and many of his novels are set in this part of the USA. Steinbeck was raised with modest means. His father, John Ernst Steinbeck, tried his hand at several different jobs to keep his family fed: He owned a feed-and-grain store, managed a flour plant and served as treasurer of Monterey County.