Copyright and the Musical Arrangement: an Analysis of the Law and Problems Pertaining to This Specialized Form of Derivative Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Approach to the Pedagogy of Beginning Music Composition: Teaching Understanding and Realization of the First Steps in Composing Music

AN APPROACH TO THE PEDAGOGY OF BEGINNING MUSIC COMPOSITION: TEACHING UNDERSTANDING AND REALIZATION OF THE FIRST STEPS IN COMPOSING MUSIC DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Vera D. Stanojevic, Graduate Diploma, Tchaikovsky Conservatory ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved By Professor Donald Harris, Adviser __________________________ Professor Patricia Flowers Adviser Professor Edward Adelson School of Music Copyright by Vera D. Stanojevic 2004 ABSTRACT Conducting a first course in music composition in a classroom setting is one of the most difficult tasks a composer/teacher faces. Such a course is much more effective when the basic elements of compositional technique are shown, as much as possible, to be universally applicable, regardless of style. When students begin to see these topics in a broader perspective and understand the roots, dynamic behaviors, and the general nature of the different elements and functions in music, they begin to treat them as open models for individual interpretation, and become much more free in dealing with them expressively. This document is not designed as a textbook, but rather as a resource for the teacher of a beginning college undergraduate course in composition. The Introduction offers some perspectives on teaching composition in the contemporary musical setting influenced by fast access to information, popular culture, and globalization. In terms of breadth, the text reflects the author’s general methodology in leading students from basic exercises in which they learn to think compositionally, to the writing of a first composition for solo instrument. -

A Practical Guide to Musical Composition Alan Belkin

1 A Practical Guide to Musical Composition by Alan Belkin [email protected] © Alan Belkin, 2008 2 Presentation The aim of this book is to discuss fundamental principles of musical composition in concise, practical terms, and to provide guidance for student composers. Many of these practical aspects of the craft of composition, especially concerning form, are not often discussed in ways useful to an apprentice composer - ways that help him to solve common problems. Thus, this will not be a "theory" text, nor an analysis treatise, but rather a guide to some of the basic tools of the trade. It is mainly based on my own experience as a composer and teacher. This book is the first in a series. The others are: Counterpoint, Orchestration, and Harmony. A complement to this book is my Workbook for Elementary Tonal Composition. For more artistic matters related to composition, please see my essay on the Musical Idea. This series is dedicated to the memory of my teacher and friend Marvin Duchow, one of the rare true scholars, a musician of immense depth and sensitivity, and a man of unsurpassed kindness and generosity. Note concerning the musical examples: Unless otherwise indicated, the musical examples are my own, and are covered by copyright. To hear the audio examples, you must use the online version of this book. To hear other examples of my music, please visit the worklist page. Scores have been reduced, and occasional detailed performance indications removed, to save space. I have also furnished examples from the standard repertoire (each marked "repertoire example"). -

Sampling and Remixes

DE FR EN SEARCH Sampling and Remixes The articles about arrangements in the “Good to know” series have so far focused on “conventional” arrangements of musical works. Sampling and remixes are two additional and specic forms of arrangement. What rights need to be secured when existing recordings are used to produce a new work? What agreements have to be contracted? Text by Claudia Kempf and Michael Wohlgemuth From the copyright point of view, remixes and sampling are specic forms of arrangement. (Photo: Tabea Hüberli) Sound samplings come in many dierent forms and techniques. But they all have one thing in common: they incorporate parts of a musical recording into a new work. This regularly raises the question whether such parts of works or samples are protected by copyright or – especially in the case of very short sound sequences – whether they may be used freely. In the case of a remix, an existing production is taken and re-arranged and re-mixed. This may involve taking apart a whole work and putting it together again with the addition of new elements. Theoretically, the degree of re-arrangement in a remix may range from a simple cover version to a completely new arrangement. As a rule, a remix is simply an arrangement. Remixes generally keep a work’s existing title and add a tag which refers either to the form of use (radio edit / extended club version, or similar) or the name of the remixer (generally a well-known DJ). By contrast with conventional arrangements, in addition to using an existing work to create a derived work or arrangement, samples and remixes also use an existing sound recording. -

MUSIC RIGHTS PRIMER Introduction

THE COMMITTEE ON ENTERTAINMENT LAW OF THE ASSOCIATION OF THE BAR OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK January, 2003 The Committee gratefully acknowledges the contributions of prior chairpersons, Noel L. Silverman and Victoria G. Traube, and of H. Joseph Mello, the initial editor. MUSIC RIGHTS PRIMER Introduction This Primer is intended to assist lawyers who are not actively engaged in the music sub- specialty of entertainment law, but who, from time to time, may be involved with matters pertaining to that area. It is also intended for law students and non-lawyers who have an interest or involvement in the entertainment industry. We envision this Primer to be used primarily to explain the different rights that fall under the generic term “music rights”, and to delineate generally which rights are necessary for projects or product in this medium. It is not intended as a replacement for an exhaustive treatise and should not be considered a substitute for specialized legal representation required to resolve the complex issues that often arise in transactions involving music rights. Rather, it is designed to highlight issues and to provide the basic understanding of the foundations of a music project. Specialists in the field should be consulted when additional legal assistance is needed. They can easily be found in New York, Los Angeles and Nashville, and to a lesser extent, in other parts of the country. This Primer deals with music rights in the United States only. While many of the principles discussed below apply in other countries as well, there may be significant differences, and resolution of foreign issues is outside the scope of this Primer. -

Glossary for Music the Glossary for Music Includes Terms Commonly Found in Music Education and for Performance Techniques

Glossary for Music The glossary for Music includes terms commonly found in music education and for performance techniques. The intent of the glossary is to promote consistent terminology when creating curriculum and assessment documents as well as communicating with stakeholders. Ability: natural aptitude in specific skills and processes; what the student is apt to do, without formal instruction. Analog tools: category of musical instruments and tools that are non-digital (i.e., do not transfer sound in or convert sound into binary code), such as acoustic instruments, microphones, monitors, and speakers. Analyze: examine in detail the structure and context of the music. Arrangement: setting or adaptation of an existing musical composition Arranger: person who creates alternative settings or adaptations of existing music. Articulation: characteristic way in which musical tones are connected, separated, or accented; types of articulation include legato (smooth, connected tones) and staccato (short, detached tones). Artistic literacy: knowledge and understanding required to participate authentically in the arts Atonality: music in which no tonic or key center is apparent. Artistic Processes: Organizational principles of the 2014 National Core Standards for the Arts: Creating, Performing, Responding, and Connecting. Audiate: hear and comprehend sounds in one’s head (inner hearing), even when no sound is present. Audience etiquette: social behavior observed by those attending musical performances and which can vary depending upon the type of music performed. Benchmark: pre-established definition of an achievement level, designed to help measure student progress toward a goal or standard, expressed either in writing or as an example of scored student work (aka, anchor set). -

Album Hunter Mp3 Download Album Hunter Mp3 Download

album hunter mp3 download Album hunter mp3 download. A fan-arrangement album celebrating the music and franchises from Super Smash Bros , featuring musicians from around the world. Harmony of Heroes is a Super Smash Bros fan-arrangement album celebrating and paying tribute to the music of Super Smash Bros, Super Smash Bros. Melee and Super Smash Bros. Brawl. It is a collaborative effort made up of musicians on a global scale, ranging from digitally synthesised music to live performances covering a variety of different genres. The diversity of the album allows us to reach out to many different types of fans no matter their musical preference. The album builds upon the success of Harmony of a Hunter and Harmony of a Hunter: 101% Run, two Metroid focused albums marking the 25 th Anniversary of the Metroid franchise. Both of these albums covered the majority of music present in Metroid games at that time, and Smash Bros felt like the next natural step in an effort to reach out to even more people. The name Heroes was chosen to describe the characters we choose in Super Smash Bros, the ones who help us reign triumphant in those epic brawls. They are our heroes. Our album is vast in content, covering the majority of franchises featured in these titles. While you can expect to hear iconic themes representing some of the game’s most notable additions, you may be surprised to find we have covered some of the more obscure ones too. In some cases, we haven’t been afraid to experiment a little, offering a fresh perspective to those who listen. -

How Understanding Arrangement Techniques Can Improve Your Songs Mike Levine on Jul 04, 2017 in Music Theory & Education 1 Comments

Arranging for Success - How Understanding Arrangement Techniques Can I : Ask.Au... Page 1 of 6 Arranging for Success - How Understanding Arrangement Techniques Can Improve Your Songs Mike Levine on Jul 04, 2017 in Music Theory & Education 1 comments Understanding some key universal concepts around arrangement, dynamics and composition can help you take your tracks to the next level. Here's how. Whether you’re in the studio or on stage, just having a strong song and performing it well is not enough. You also need a smart arrangement in order for your song to have its maximum impact. Giving your arrangement a dramatic arc helps make it more interesting and accessible to listeners. It's beyond the scope of this article to focus on specific instruments and how to arrange them for particular musical genres—that would require a series of books—but the aim here is to cover some global arranging concepts, which will apply no matter what the specific style or instrumentation. Contrast is King Just like a painting, a song arrangement needs contrast. If everything is too similar, it will be boring and the listeners will tune out. You want to keep their attention, so you should structure the song so that it’s not static. Think of it almost like a book or play, which has a beginning a middle and an end. You have a number of tools at your disposal for creating drama and interest with your arrangement, which include varying the dynamics, adding to the instrumentation as you go, and building the complexity of the instrument and vocal parts as the song progresses. -

Musical and Literary Composition: the Revision Relation

Musical and Literary Composition: The Revision Relation CODY RIEBEL Produced in Dan Martin’s Fall 2012 ENC1102 Introduction Compositional research has determined why and how writers think, plan, write, and revise, to name just a few processes. Janet Emig has stressed that writing is a unique process between forms of language and composition (“Writing…” 122). Therefore, several modes and variations of writing have distinct characteristics yet to be examined. Composition in music is an incredibly diverse process that requires more examination. Writing for musicians isn’t exactly a routine process. Inspiration, improvisation, and emotion are just a few of the factors characteristic of their processes that set it apart from other types of writing. Revision in musical composition is also a unique part of musicians’ writing. However, musical revision still involves some of the same types and methods of revision used by writers. Revision in writing has certainly been explored in multiple aspects. Strategies for revising have been examined, but revision methods in various disciplinary writing processes have not been connected. To understand musicians’ writing processes, the most important piece of their processes must first be understood: revision. This examination should prove relevant towards what we have already analyzed about writing and revising and serve to answer the question, “What is the relationship between the revising processes of musicians and writers?” A valid comparison would prove valuable to understanding musical composition and determining methods to improve musicians’ writing habits. Revision seems to dominate the composing process of most musicians. The initial explanation involves the multiple reasons composers need to revise their work: molding the text with the melody, trying to fit words in a specific meter, and accommodating other variables unique to musical revision. -

Arrangements and Editions of Public Domain Music: Originally in a Finite System

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 34 Issue 1 Article 6 1983 Arrangements and Editions of Public Domain Music: Originally in a Finite System Ronald P. Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ronald P. Smith, Arrangements and Editions of Public Domain Music: Originally in a Finite System, 34 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 104 (1983) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol34/iss1/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. ARRANGEMENTS AND EDITIONS OF PUBLIC DOMAIN MUSIC: ORIGINALITY IN A FINITE SYSTEM* Copyright law seeks toprotect originality,in the context of derivativemusic, how- ever, courts have struggled to dfne originality. Hampered by unfamiliarity with musical terminology and basic compositional techniques, courts have gropedfor standardsof easy application. But originality is not amenable to bright line stan- dards. Indeed,stark distinctions between originalityand nonoriginalityare neither feasible nor responsible. This Note critiques existingjudicial standardsfor assessing the originalityof derivative works and offers suggestionsfor a moreflexible alloca- tion of copyright protection. It identoes the conflicting goals of copyright law-protecting a composer's originality while preserving the availability ofpublic domain music andideas--anddemonstrateshow those goals may be reconciled Fi- nally, the Note explores the benefts and limitations of expert testimony in musical copyright litigation, and shows how experts, without usurping the judicialfunction, can assist courts in reaching more sophisticateddecisions. -

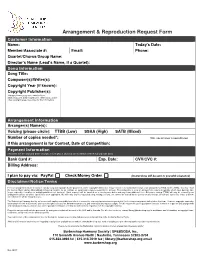

Arrangement & Reproduction Request Form

Arrangement & Reproduction Request Form Customer Information Name: Today’s Date: Member/Associate #: Email: Phone: Quartet/Chorus/Group Name: Director’s Name (Lead’s Name, if a Quartet): Song Information Song Title: Composer(s)/Writer(s): Copyright Year (if known): Copyright Publisher(s): (Research www.ascap.com, www.bmi.com, www.sesac.com, www.songfile.com, sheet music, and/or other copyright-related resources for this information) Arrangement Information Arranger(s) Name(s): Voicing (please circle): TTBB (Low) SSAA (High) SATB (Mixed) Number of copies needed*: *(One copy per singer is required by law) If this arrangement is for Contest, Date of Competition: Payment Information (You will not be charged until clearance is in place and you are notified of the total amount due.) Bank Card #: Exp. Date: CVV/CVC #: Billing Address: I plan to pay via: PayPal ccc Check/Money Order ccc (Instructions will be sent to you with clearance) Disclaimer/Notice/Terms Fees for arrangement music clearances vary by song and copyright holder (publisher). Some copyright holders also charge extra fees for additional voicings of an arrangement (TTBB, SSAA, SATB). You may email the Society Music Library ([email protected]) anytime for an estimate on a particular song you would like to arrange. Processing time to clear an arrangement request is typically 30-60 days, but may take longer especially if medleys or multiple publishers are involved. Rush requests will be handled on a case-by-case basis and may incur additional fees. Only male voicing (TTBB) will only be cleared for an arrangement unless otherwise specified on your application. -

MM Discography -- Others Updated 2016

MONDAY MICHIRU DISCOGRAPHY -- OTHERS 1976 Toshiko Akiyoshi & Lew Tabackin Big Band "Insights" album (RCA) -- vocals 1980 Toshiko Akiyoshi Trio & Flute Quartet "Tuttie Flutie" album (Discomate Records) -- flute 1991 System 7 "Freedom Fights" single (Ten Records) -- vocals 1992 "Jazz Hip Jap" compilation CD (NEC Avenue) -- co-writer, arranger & vocals 1993 United Future Organization "United Future Organization" album and single "My Foolish Dream" (Brownswood Records) -- co-writer and vocals BBF & Zum Zum Allstars "Zum Zum Paradise" album (Ki/oon Sony Records) -- co-writer and vocals "Jazz Hip Jap 2" compilation CD (NEC Avenue) -- co-writer, arranger and vocals 1994 Remix Trax Vol. 6 "Japanese New Vibes" compilation album (Meldac) -- co-writer and vocals DJ Krush "Krush" album (Chance Records) -- co-writer and vocals "Yeah!" compilation CD (Kitty) -- song licensed from "Maiden Japan" album Audio Sports "Strange Fruits" album (All Access) -- co-writer and vocals Kyoto Jazz Massive "Kyoto Jazz Massive" album (For Life) -- vocals "Cool Struttin' Volume 3" compilation album (Amber/Polydor) -- song licensed from "Maiden Japan" album Picasso "Breakfast Newspaper" album (Kitty) -- lyrics and vocals 1995 Eiki Nonaka "a-key" album (Mercury Records) -- writer and vocals "Cutie Collection" compilation album (Media Remoras) -- co-writer and vocal production "Jazz Moments by Heineken Volume 1" album (Polydor) -- compiled by myself "Denz da Denz Vol. 2" compilation CD (Basic Beats) -- song licensed from "Adoption Agency" album Mondo Grosso "Born Free" -

One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and Their Fans

One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and their Fans Annie Lyons TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin December 2020 __________________________________________ Renita Coleman Department of Journalism Supervising Professor __________________________________________ Hannah Lewis Department of Musicology Second Reader 2 ABSTRACT Author: Annie Lyons Title: One Direction Infection: Media Representations of Boy Bands and their Fans Supervising Professors: Renita Coleman, Ph.D. Hannah Lewis, Ph.D. Boy bands have long been disparaged in music journalism settings, largely in part to their close association with hordes of screaming teenage and prepubescent girls. As rock journalism evolved in the 1960s and 1970s, so did two dismissive and misogynistic stereotypes about female fans: groupies and teenyboppers (Coates, 2003). While groupies were scorned in rock circles for their perceived hypersexuality, teenyboppers, who we can consider an umbrella term including boy band fanbases, were defined by a lack of sexuality and viewed as shallow, immature and prone to hysteria, and ridiculed as hall markers of bad taste, despite being driving forces in commercial markets (Ewens, 2020; Sherman, 2020). Similarly, boy bands have been disdained for their perceived femininity and viewed as inauthentic compared to “real” artists— namely, hypermasculine male rock artists. While the boy band genre has evolved and experienced different eras, depictions of both the bands and their fans have stagnated in media, relying on these old stereotypes (Duffett, 2012). This paper aimed to investigate to what extent modern boy bands are portrayed differently from non-boy bands in music journalism through a quantitative content analysis coding articles for certain tropes and themes.