Water Resource Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cobb County, Georgia and Incorporated Areas

VOLUME 1 OF 4 Cobb County COBB COUNTY, GEORGIA AND INCORPORATED AREAS COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER ACWORTH, CITY OF 130053 AUSTELL, CITY OF 130054 COBB COUNTY 130052 (UNINCORPORATED AREAS) KENNESAW, CITY OF 130055 MARIETTA, CITY OF 130226 POWDER SPRINGS, CITY OF 130056 SMYRNA, CITY OF 130057 REVISED: MARCH 4, 2013 FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 13067CV001D NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) report may not contain all data available within the Community Map Repository. Please contact the Community Map Repository for any additional data. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) may revise and republish part or all of this FIS report at any time. In addition, FEMA may revise part of this FIS report by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS report. Therefore, users should consult with community officials and check the Community Map Repository to obtain the most current FIS report components. Initial Countywide FIS Effective Date: August 18, 1992 Revised Countywide FIS Effective Date: December 16, 2008 Revised Countywide FIS Effective Date: March 4, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Purpose of Study 1 1.2 Authority and Acknowledgments 1 1.3 Coordination 3 2.0 AREA STUDIED 5 2.1 Scope of Study 5 2.2 Community Description 10 2.3 Principal Flood Problems -

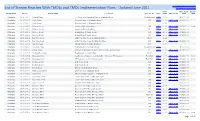

List of TMDL Implementation Plans with Tmdls Organized by Basin

Latest 305(b)/303(d) List of Streams List of Stream Reaches With TMDLs and TMDL Implementation Plans - Updated June 2011 Total Maximum Daily Loadings TMDL TMDL PLAN DELIST BASIN NAME HUC10 REACH NAME LOCATION VIOLATIONS TMDL YEAR TMDL PLAN YEAR YEAR Altamaha 0307010601 Bullard Creek ~0.25 mi u/s Altamaha Road to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River FC 2012 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 2006 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Beards Creek Spring Branch to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010603 Five Mile Creek Headwaters to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010603 Goose Creek U/S Rd. S1922(Walton Griffis Rd.) to Little Goose Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Mushmelon Creek Headwaters to Delbos Bay Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010604 Altamaha River Confluence of Oconee and Ocmulgee Rivers to ITT Rayonier -

Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards ( 1) Purpose. The establishment of water quality standards. (2) W ate r Quality Enhancement: (a) The purposes and intent of the State in establishing Water Quality Standards are to provide enhancement of water quality and prevention of pollution; to protect the public health or welfare in accordance with the public interest for drinking water supplies, conservation of fish, wildlife and other beneficial aquatic life, and agricultural, industrial, recreational, and other reasonable and necessary uses and to maintain and improve the biological integrity of the waters of the State. ( b) The following paragraphs describe the three tiers of the State's waters. (i) Tier 1 - Existing instream water uses and the level of water quality necessary to protect the existing uses shall be maintained and protected. (ii) Tier 2 - Where the quality of the waters exceed levels necessary to support propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and recreation in and on the water, that quality shall be maintained and protected unless the division finds, after full satisfaction of the intergovernmental coordination and public participation provisions of the division's continuing planning process, that allowing lower water quality is necessary to accommodate important economic or social development in the area in which the waters are located. -

Georgia Cobb Marietta

Form 10-306 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Oct. 1972) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Georgia NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Cobb INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) COMMON: _JVr ~~ " ~ • : - Kennesaw Mountain National:Battlefield Park AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET AND NUMBER: P. O. : BOK 1167 On western edge of Marietta, GA^just .of£ US CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: Marietta 7th STATE: COUNTY: , CODE Georgia : 137: . Cobb 067 ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS TO THE PUBLIC District | | Building L7Q Public Public Acquisition: Occupied Yes: Site' Q Structure L~3 Private Q In Process Unoccupied Qtl Restricted Q Object C] Both Q Being Considered Preservation work | | Unrestricted- in progress PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) Q Agricultural [_J Government | | Transportation Comments t - [~~1 Commercial | | Industrial Q Private Residence Other fSpec/fy; [ ] Educational [^Military Q Religious | 1 Entertainment [~~| Museum I | Scientific Ui IU National Park ^Service, Kenne'saw Mountain National. Battlefield Park REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (I! applicable) STREET AMD NUMBER: Southeast Region Cl TY OR TOWN: Atlanta COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC: Cobb County Courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: 177 Washington Avenue, N. ; E CITY_OR TOWN: Marietta TITLE OF SURVEY: None DATE OF SURVEY: DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: (Check One) f~l Excellent Stl Good Q Fair I | Deteriorated [ | Ruin* Q Unexpoted CONDITION (Check One) (Check One) (2Q Altered Q Unaltered Q Moved (X) Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (it known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Kennesaw Mountain is an erosional granitic hornblende remnant located in the upper Georgia Piedmont. -

Fecal Coliform TMDL Report

Total Maximum Daily Load Evaluation for Nineteen Stream Segments in the Tennessee River Basin for Fecal Coliform Submitted to: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 4 Atlanta, Georgia Submitted by: The Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division Atlanta, Georgia January 2004 Total Maximum Daily Load Evaluation January 2004 Tennessee River Basin (Fecal coliform) Table of Contents Section Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................. iv 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Watershed Description......................................................................................................1 1.3 Water Quality Standard.....................................................................................................5 2.0 WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT ........................................................................................ 8 3.0 SOURCE ASSESSMENT ...................................................................................................... 9 3.1 Point Source Assessment ................................................................................................. 9 3.2 Nonpoint Source Assessment........................................................................................ -

Effects of Internal Loading on Algal Biomass in Lake Allatoona, a Southeastern Piedmont Impoundment

EFFECTS OF INTERNAL LOADING ON ALGAL BIOMASS IN LAKE ALLATOONA, A SOUTHEASTERN PIEDMONT IMPOUNDMENT by Elena Louise Ceballos (Under the direction of Todd C. Rasmussen) Abstract Cultural eutrophication of lakes is the accelerated nutrient enrichment resulting in detri- mental ecological effects such as algal blooms, lake anoxia and toxic metal release from sediments. Cultural eutrophication is a common occurrence in Piedmont impoundments in Georgia, as well as lakes and impoundments throughout the world. It often results in water unsafe for agricultural use, recreation and drinking. To reduce the cultural eutrophication of local Piedmont impoundments, recent regulatory controls for nutrients were established as part of the Clean Lakes program and court-ordered total maximum daily loads (TMDLs). These regulatory efforts focus on the reduction and minimization of point-source watershed nutrient inputs, primarily phosphorus, into lake sys- tems, as P is the limiting nutrient in Piedmont impoundments. Thus, reductions in phos- phorus loading are expected to improve lake water quality. However, in the Piedmont, as well as worldwide, many lakes continue to experience algal blooms and lake anoxia after sources of external loading are discontinued. The process of nutrient desorption from sediments, known as internal loading, has been identified to be a source of algal-available P, as well as other nutrients. The conditions under which internal loading takes place are region-specific as they vary based on local physical, chemical and biological conditions. The purpose of our research was to quantify changes in algal biomass in response to internal loading in Southeast Piedmont impoundments. The results from a mesocosm exper- iment, physical and chemical sediment analysis, and algal assays were used to characterize algal-availabile phosphorus in Southeastern Piedmont impoundments. -

2018 Integrated 305(B)

2018 Integrated 305(b)/303(d) List - Streams Reach Name/ID Reach Location/County River Basin/ Assessment/ Cause/ Size/Unit Category/ Notes Use Data Provider Source Priority Alex Creek Mason Cowpen Branch to Altamaha Not Supporting DO 3 4a TMDL completed DO 2002. Altamaha River GAR030701060503 Wayne Fishing 1,55,10 NP Miles Altamaha River Confluence of Oconee and Altamaha Supporting 72 1 TMDL completed TWR 2002. Ocmulgee Rivers to ITT Rayonier GAR030701060401 Appling, Wayne, Jeff Davis Fishing 1,55 Miles Altamaha River ITT Rayonier to Penholoway Altamaha Assessment 20 3 TMDL completed TWR 2002. More data need to Creek Pending be collected and evaluated before it can be determined whether the designated use of Fishing is being met. GAR030701060402 Wayne Fishing 10,55 Miles Altamaha River Penholoway Creek to Butler Altamaha Supporting 27 1 River GAR030701060501 Wayne, Glynn, McIntosh Fishing 1,55 Miles Beards Creek Chapel Creek to Spring Branch Altamaha Not Supporting Bio F 7 4a TMDL completed Bio F 2017. GAR030701060308 Tattnall, Long Fishing 4 NP Miles Beards Creek Spring Branch to Altamaha Altamaha Not Supporting Bio F 11 4a TMDL completed Bio F in 2012. River GAR030701060301 Tattnall Fishing 1,55,10,4 NP, UR Miles Big Cedar Creek Griffith Branch to Little Cedar Altamaha Assessment 5 3 This site has a narrative rank of fair for Creek Pending macroinvertebrates. Waters with a narrative rank of fair will remain in Category 3 until EPD completes the reevaluation of the metrics used to assess macroinvertebrate data. GAR030701070108 Washington Fishing 59 Miles Big Cedar Creek Little Cedar Creek to Ohoopee Altamaha Not Supporting DO, FC 3 4a TMDLs completed DO 2002 & FC (2002 & 2007). -

Flood Sept 21, 2009, Part 1

HopkinsHopkins RoadRoad FlyoverFlyover SweetwaterSweetwater ParkPark www.digitalglobe.com/index.php/48/Products?product _id=2 Pavia Circle Caraustar Facility Chastain Meadows Parkway Austell Powder Springs Road Lessons Learned • After a flooding disaster the public could care less about: – …how much it rained; or – …what frequency the rain event was; or – …how saturated the ground was; or – …how many culverts became clogged; or – …whether or not they should have had flood insurance Lessons Learned • All the general public wants to know is… …what government will do and how fast Lessons Learned • Many – …living in the floodplain still do not have flood insurance – …do not understand what the FEMA floodplain maps represent – …private Dam Owners do not understand or accept what their individual responsibilities are… Statistics • The rains returned water levels in the region’s two largest reservoirs, Lake Lanier and Allatoona Lake to pre-drought levels: – Lake Lanier rose by more than 3-ft to Elevation 1068 by September 25th and returned to full pool in October – Allatoona Lake rose to Elevation 853.25 on September 23, more than 13 feet above flood Pool at Elevation 840. Statistics • In Cobb County, the following creeks reached or exceeded the 500-year frequency event: – Sweetwater Creek – Noses Creek – Noonday Creek – Butler Creek, and – Powder Springs Creek Statistics • On Sweetwater Creek near Austell… – High Water Marks showed peak stage of record at 30.8 ft – Previous peak stage recorded 7/11/2005) from Hurricane Dennis at 21.87 ft. – -

2014 Chapters 3 to 5

CHAPTER 3 establish water use classifications and water quality standards for the waters of the State. Water Quality For each water use classification, water quality Monitoring standards or criteria have been developed, which establish the framework used by the And Assessment Environmental Protection Division to make water use regulatory decisions. All of Georgia’s Background waters are currently classified as fishing, recreation, drinking water, wild river, scenic Water Resources Atlas The river miles and river, or coastal fishing. Table 3-2 provides a lake acreage estimates are based on the U.S. summary of water use classifications and Geological Survey (USGS) 1:100,000 Digital criteria for each use. Georgia’s rules and Line Graph (DLG), which provides a national regulations protect all waters for the use of database of hydrologic traces. The DLG in primary contact recreation by having a fecal coordination with the USEPA River Reach File coliform bacteria standard of a geometric provides a consistent computerized mean of 200 per 100 ml for all waters with the methodology for summing river miles and lake use designations of fishing or drinking water to acreage. The 1:100,000 scale map series is apply during the months of May - October (the the most detailed scale available nationally in recreational season). digital form and includes 75 to 90 percent of the hydrologic features on the USGS 1:24,000 TABLE 3-1. WATER RESOURCES ATLAS scale topographic map series. Included in river State Population (2006 Estimate) 9,383,941 mile estimates are perennial streams State Surface Area 57,906 sq.mi. -

Summary of Results

Review Draft Synopsis Report Current Assimilative Capacity Assessment SUMMARY OF RESULTS In support of the Georgia Comprehensive State-wide Water Management Plan (GA State Water Plan), the Surface Water Quality (or Assimilative Capacity) Resource Assessment was used to determine the capacity of Georgia’s surface waters to absorb pollutants without unacceptable degradation of water quality. Assimilative Capacity is defined as the amount of contaminant load that can be discharged to a specific waterbody without exceeding water quality standards or criteria. In other words, the assimilative capacity is used to define the ability of a waterbody to naturally absorb and use a discharged substance without water quality becoming impaired or aquatic life being harmed. The assimilative capacity resource assessment included developing water quality models of selected streams, rivers, lakes and estuaries throughout the State of Georgia. Results from these models were compared with applicable water quality standards. The current assimilative capacity results focus on dissolved oxygen, nutrients, specifically nitrogen and phosphorus, and chlorophyll-a. The water quality models were used to evaluate the impacts of current wastewater and industrial discharges and withdrawals, land use, and meteorological conditions on the waterbody. MODELS USED FOR ASSIMILATIVE CAPACITY RESOURCE ASSESSMENT For the Assimilative Capacity Resource Assessment, four different models were developed. GA Dosag Georgia Dosag (GA Dosag) was used to predict dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations in a stream or river during critical time periods which include low flow and high temperatures. GaEst Georgia Estuary (GaEst) was used to predict the dissolved oxygen sag curve in the vicinity of waste discharge points in Georgia estuaries. -

Monthly SPLOST Financial Report 12-02-20.Xlsx

2005 SPLOST Update December 3, 2020 Amount Remaining In Department Name Project # Project Name Current Budget Encumbrances Actual Expenditures Project Department Of Transportation D0000 2005 SPLOST TIP SHARED COST 22,405,173.60 - 18,290,234.26 4,114,939.34 Department Of Transportation D1000 BRIDGE REHABILITATION/REPLACEMENT SHARED COST 2,227,375.71 - 2,227,375.71 - Department Of Transportation D1010 BELLS FERRY ROAD - NOONDAY CREEK TRIBUTARY 775,457.72 - 775,457.72 - Department Of Transportation D1020 BOOTH ROAD - OLLEY CREEK TRIBUTARY 642,125.37 - 642,125.37 - Department Of Transportation D1030 BURNT HICKORY ROAD - MUD CREEK 1,164.56 - 1,164.56 - Department Of Transportation D1040 CANDY LANE - OLLEY CREEK 1,182.08 - 1,182.08 - Department Of Transportation D1050 CANTON ROAD - LITTLE NOONDAY CREEK 1,484,536.59 - 1,484,536.59 - Department Of Transportation D1060 CHEATHAM HILL ROAD - WARD CREEK 577,656.11 - 577,656.11 - Department Of Transportation D1070 COLLINS BOULEVARD -BUTTERMILK CREEK 954,264.36 - 954,264.36 - Department Of Transportation D1080 COLLINS ROAD - LITTLE ALLATOONA CREEK 1,351.88 - 1,351.88 - Department Of Transportation D1090 COLUMNS DRIVE - SOPE CREEK 27,446.09 - 27,446.09 - Department Of Transportation D1100 CONCORD ROAD - SILVER COMET TRAIL 524,500.28 - 524,500.28 - Department Of Transportation D1110 FLINT HILL ROAD - OLLEY CREEK 574,671.38 - 574,671.38 - Department Of Transportation D1120 GARRETT ROAD - POWDER SPRINGS CREEK 1,282,088.96 - 1,282,088.96 - Department Of Transportation D1130 HAMBY ROAD - CLARK CREEK 630,761.53 -

Federal Register/Vol. 73, No. 129/Thursday, July 3, 2008/Rules and Regulations

38132 Federal Register / Vol. 73, No. 129 / Thursday, July 3, 2008 / Rules and Regulations required,’’ 445B.5915, ‘‘Requirements emissions prohibited,’’ 445B.6115, of Environmental Protection describing for registration of vehicle temporarily ‘‘Exemption of vehicle from certain an upgrade to the NV2000 emission being used and maintained in another provisions,’’ 445B.6125, ‘‘Certification analyzer to make emissions testing state,’’ 445B.592, ‘‘Applicability of of vehicle for exemption,’’ 445B.7015, possible on motor vehicles containing a certain standards for emissions and ‘‘Annual and additional inspections,’’ certified on-board diagnostic system other requirements,’’ 445B.593, 445B.7025, ‘‘Alteration of emission which uses controller area network ‘‘Evidence of compliance required for control system of vehicle used to communication. certain vehicles based in Clark County,’’ conduct inspection,’’ 445B.7035, PART 81—[AMENDED] 445B.594, ‘‘Evidence of compliance ‘‘Preliminary written notice of violation; required for certain vehicles based in reinspection of vehicle,’’ 445B.7045, I 3. The authority citation for part 81 Washoe County,’’ 445B.595 (excluding ‘‘Administrative fines and other continues to read as follows: subsection(2)), ‘‘Inspections of vehicles penalties for certain violations,’’ 445B.727, ‘‘Administrative fines and owned by State or political subdivisions Authority: 42 U.S.C. 7401 et seq. other penalties,’’ and 445B.735, or operated on federal installations,’’ ‘‘Program for licensure to install, repair Subpart C—[Amended] 445B.596, ‘‘Standards for emissions,’’ and adjust devices for control of 445B.598, ‘‘Imposition and statement of emissions.’’ I 4. In § 81.329, the table entitled fee for inspection and testing; listing of (ii) Additional material. ‘‘Nevada—Carbon Monoxide’’ is stations and fees,’’ 445B.599, (A) Nevada Division of Environmental amended by revising the entry for the ‘‘Prescription and notice of maximum Protection.