“This Is My Texas A&M:” the Interplay of Institutional and Individual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SENATE—Wednesday, April 6, 2011

5196 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 157, Pt. 4 April 6, 2011 SENATE—Wednesday, April 6, 2011 (Legislative day of Tuesday, April 5, 2011) The Senate met at 9:30 a.m., on the SCHEDULE Every time we have agreed to meet in expiration of the recess, and was called Mr. REID. Madam President, last the middle, they have moved where the to order by the Honorable KIRSTEN E. night we were finally able to arrive at middle is. They said no when we met GILLIBRAND, a Senator from the State an agreement on the small business them halfway, and now they say: It is of New York. jobs bill—or at least a way to get rid of our way or the highway. That is no way to move forward. some very important amendments that PRAYER People ask: Why is this so difficult? we will vote on around 4 o’clock this They ask: Can’t you just get it done? I The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- afternoon. There will be seven rollcall understand how they feel, and I share fered the following prayer: votes. their frustrations, but this is why it is Let us pray. This morning, there will be a period so tough. It is like trying to kick a Merciful Father, who put into our of morning business until 11 a.m., with field goal and the goalposts keep mov- hearts such deep desires that we can- the time until 10:40 a.m. equally di- ing. not be at peace until we rest in You, vided and controlled between the ma- The Democrats’ bottom line has not remove from our lives anything that jority and the Republicans. -

100 Years of Aggie B Asketb

Texas A&M AGGIES (12-12, 3-9) at Texas Tech RED RAIDERS (8-16, 1-11) 2011 Tuesday, Feburary 14, 2012 • 6:02 PM CT • TV: ESPN2 HD 2012 United Spirit Arena (15,000) • Lubbock, Texas GAME 25 Media Relations Contact: Matt Simon • [email protected] • O: (979) 862-5451 • C: (979) 255-0469 Record ................................... 12-12, 3-9 Big 12 Head Coach ....Billy Kennedy (SE Louisiana '86) Media Coverage Ranking .........................................................NR Record ............................223-191 (14th year) TELEVISION .........................................ESPN2 HD Streak ..................................................... Lost 4 at Texas A&M.....................12-12 (first year) Dave Armstrong .............................Play-by-Play Last 5 / Last 10 ................................ 1-4 / 3-7 vs. Texas Tech ..........................................1-0 Paul Biancardi ................................ Commentary on the Road ................................................. 1-8 RADIO....................Texas A&M Sports Network Last Game ........lost to Iowa State (A), 69-46 (Sat.) Dave South .....................................Play-by-Play Al Pulliam ........................................ Commentary Local ...........................................WTAW-AM 1620 Record .....................................8-16, 1-11 Big 12 Head Coach ...Billy Gillispie (Texas State '83) Satellite Radio ................. Sirius 94 (Tech feed) Ranking .........................................................NR Record .........................148-101 -

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 2014 (Business Casual Dress) Transportation Provided to Welcome Reception

CHANCELLOR’S CENTURY COUNCIL ANNUAL MEETING FEBRUARY 20 - 21, 2014 COLLEGE STATION, TEXAS THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 2014 (Business Casual Dress) Transportation Provided to Welcome Reception 11 a.m. Executive Committee Meeting & Luncheon Hilton Ballroom 3 (Chancellor’s Cabinet Members are invited.) 1 p.m. Annual Meeting Registration Hilton Ballroom 2 2 p.m. Welcome & Opening Session Hilton Ballroom 4 Nancy & J. Brad Allen, CCC General Chairs John Sharp, Chancellor, The Texas A&M University System 2:45 p.m. The Texas A&M University System Briefings Part I Flavius C. Killebrew, President and CEO, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi “FAA Unmanned Aircraft System Test Site” Dennis Christiansen, Director, Texas A&M Transportation Institute “Accelerate Texas” “Kyle Field Game Day Traffic” 3:45 p.m. Break & Hotel Check-In (Check-In Time 4 p.m.) 4:15 p.m. The Texas A&M University System Briefings Part II Billy C. Hamilton, Executive Vice Chancellor and Chief Financial Officer, A&M System “Price Waterhouse Cooper Administrative Review” “Guaranteed Four-Year Tuition” James Hallmark, Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs, A&M System “Texas A&M University at Nazareth-Peace Campus” “Texas A&M-Kingsville and Premont ISD Partnership” “College Credit for Heroes” 5 p.m. Adjourn 5:45 p.m. Depart Hilton Hotel for Blue Bell Park Private Vehicles – Blue Bell Park Parking Available in Lot 100j Entrance on Olsen Blvd. 6-8 p.m. Welcome Reception The Kay & Jerry S. Cox Diamond Club at Blue Bell Park FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 21, 2014 (Business Casual Dress) Transportation Provided to all Venues 7:30 a.m. -

List of Potential Club Meeting Speakers – Spring 2019

List of Potential Club Meeting Speakers – Spring 2019 Speaker's Bureau https://www.aggienetwork.com/speakersbureau/ This is a searchable site to find speakers. You must create an account to use the site. Ron Schaefer City of College Station Parks & Recreation Department (979) 764-3738 [email protected] http://fieldofhonor.cstx.gov/ The City of College Station municipal cemetery. A special section of this project has been designated as the “Aggie Field of Honor”. The AFOH, within view of Kyle Field, will have special gates, and monuments. It will be unique place for former students, friends of Aggies and Aggie fans. It truly is location that embodies the sprits and traditions of Aggies. Spaces are available in the AFOH. Student Body President Student Body President, Texas A&M University (979)845-3051 [email protected] Dr. Jennifer Bohac 87 Director of Travel Program, The Association of Former Students (979) 845-7514 [email protected] Hear about all the phenomenal trips available through The Association of Former Students Travel Program. Mr. Harold Byler, Jr. '50Author (325) 597-8933 [email protected] Author of book "Life at Aggieland in the 40’s" and presentation on the same. He will travel up to 75 miles from Brady, TX. Mr. Greg Winfree Director, Texas Transportation Institute (979) 845-1713 ext. 51713 [email protected] Transportation issues, transportation research Dr. Douglas Palmer Dean, College of Education and Human Development (979) 862-6649 [email protected] Over 7,000 Aggie educators working in Texas public schools! Please limit engagements to Houston area, Dallas/Ft. -

2016-17 Women's Basketball Game Notes

2016-17 Women’s Basketball Game Notes 2011 National Champions • 13-time NCAA Tournament Participant • 2013 SEC Tournament Champions Women’s Basketball SID David Waxman | [email protected] | Cell: (832) 326-2863 Wednesday, November 23, 2016 • 6:30 p.m. 2016-17 Schedule & Results 3-0 Overall, 0-0 SEC AT Date A&M Rk. Opp. Rk. Opponent Time/Result Nov. 13 rv/23 Central Arkansas W, 74-49 Nov. 17 rv/24 Texas Tech W, 98-90 OT No. 25 Coaches’ Nov. 20 rv/24 Stephen F. Austin W, 63-48 Texas A&M Aggies Little Rock Trojans Nov. 23 rv/25 at Little Rock 6:30 p.m. (3-0, 0-0 SEC) (1-3, 0-0 Sun Belt) Nov. 26 rv/25 Abliene Christian 6 p.m. Little Rock, Ark. | Jack Stephens Center (5,600) Nov. 30 Southern Cal 11 a.m. None | KZNE 1150 AM (Tom Turbiville, Bret Dark) Dec. 5 at SMU 7 p.m. On The Aggies Dec. 8 at TCU 7:30 p.m. Dec. 10 Texas A&M-Corpus Christi 2 p.m. • The Aggies are 3-0 for the third straight year and tenth time in the past 11 seasons Campbell Center, Houston, Texas • Texas A&M is the only school in the country with at least one player who ranks in the top 10 nationally in Dec. 17 vs. Southern 2:30 p.m. points per game (D. Williams, 7th), rebounds per game (Howard, 7th) and assists per game (Knox, 3rd) Florida Sunshine Classic, Warden Arena, Winter Park, Fla. -

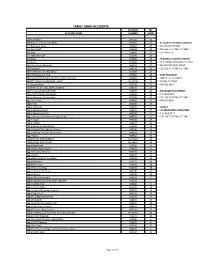

Tamf/ Tamu Accounts Account Mc Account Name Number Code

TAMF/ TAMU ACCOUNTS ACCOUNT MC ACCOUNT NAME NUMBER CODE 12th Law Man 960510 31 180 Degrees Consulting TAMU 955680 25 ST. MARY'S CATHOLIC CHURCH 2nd Regiment Staff 953810 20 603 CHURCH STREET 2nd Wing Staff 954000 20 COLLEGE STATION, TX 77840 30-Loves 958610 27 979- 846-5717 3rd Regiment Staff 953060 20 3rd Wing 943400 20 EPISCOPAL STUDENT CENTER A Battery 953690 20 ST. THOMAS EPISCOPAL CHURCH A&M Christian Fellowship 954710 23 902 GEORGE BUSH DRIVE A&M Esports 949530 26 COLLEGE STATION, TX 77840 A&M International Fellowship 952830 23 A&M Photography Club 947060 26 HOST PROGRAM A&M United Methodist Church's College Ministry 945010 23 2040 W. VILLA MARIA ABBOTT FAMILY LEADERSHIP - MSC* 05-57296 21 BRYAN, TX 77807 A-Company Band 953320 20 979-209-2924 Active Minds at Texas A&M University 948910 17 ADOPT-A-JOURNAL ARCHIVES 510458 26 BREAKAWAY MINISTRIES Adventist Christian Fellowship 955130 23 P. O. BOX 9727 African Students Association 952300 15 COLLEGE STATION, TX 77845 Ag Law Society 960490 31 979-693-9869 Aggie Aces 952030 27 Aggie Actuaries 942830 3 IMPACT Aggie Adaptive Sports 950930 14 c/o BREAKAWAY MINISTRIES Aggie Advertising Club 946270 6 P. O. BOX 9727 Aggie Aerospace Women in Engineering 948350 8 COLLEGE STATION, TX 77845 Aggie Angels 959100 27 Aggie Anglers 959110 26 Aggie Aquarium Association 951030 26 Aggie Artificial Intelligence Society 948230 26 Aggie Athletic Trainers' Association 946910 26 Aggie Babes 948640 26 AGGIE BAND ENDOWMENT 04-57022 20 AGGIE BAND HALL (NEW) 05-73327 20 Aggie Bandsmen 953510 20 Aggie Beef Cattle -

The Texas A&M Foundation Magazine | Spring 2012

THE TEXAS A&M FOUNDATION MAGAZINE | S P R I N G 2 0 1 2 PresiDent’s letter is Your Class in the top 20? everal years ago, i visited with an old friend and former commandant at the u.s. air Force academy, Gen. Pat Gamble ’67. Pat lamented the absence of a class system at the air Force academy, which he said led to a “me first at all costs” environment. he said the heavy competition and elevation through the cadet ranks was based purely on individual achievement relative to others. our chat made me realize what a profound influence the class system has on texas a&M. the experience of being differentiated by class has been powerful throughout most of our history. in addition to achievement and elevation through cadet ranks, the class system provided the opportunity for emergent leaders— your classmates bestowed the mantle of leadership based on your innate qualities and ability to have them follow you with no prescribed authority. our class system has also created rivalry between classes, building a “we” above “me” attitude among aggies. With time the rivalry fades to some degree, but we never lose it. it certainly has not faded within the Class of ’67, and i take pride in doing my part to egg on the rivalry—both with other classes and among my classmates—in regards to giving back to texas a&M. the Class of ’67 is nowhere close to the most philanthropic class. Many of us arrived on campus as the sons of sharecroppers and refinery workers. -

2015-16 Wo E 'S B Sketb Ll G E Notes

2015-16 Woe’s Bsketbll Ge Notes 2011 National Champions • 13-time NCAA Tournament Participant • 2013 SEC Tournament Champions Women’s Basketball SID David Waxman | [email protected] | Cell: (832) 326-2863 Game 32 • NCAA Second Round • Monday, March 21, 2016 • 5:30 p.m. 2015-16 Schedule & Results No. 17 Associated Press / No. 10 Coaches’ Location 22-9 Overall, 11-5 SEC College Station, Texas [5] Florida State Seminoles Date A&M Rk. Opp. Rk. Opponent Time/Result Arena Nov. 13 13/16 Texas State W, 87-50 (24-7, 13-3 ACC) Reed Arena (12,989) Head Coach: Sue Semrau Television Nov. 15 13/16 Southern W, 88-47 Nov. 18 12/12 14/9 at Duke W, 72-66 OT No. 18 Associated Press / No. 18 Coaches’ (Paul Sunderland, Nov. 21 12/12 TCU W, 82-78 [4] Texas A&M Aggies Chiney Ogwumike) South Point Thanksgiving Shootout, South Point Arena, Las Vegas, Nev. (22-9, 11-5 SEC) Radio Nov. 27 10/9 16/15 vs. Cal W, 75-58 Head Coach: Gary Blair Texas A&M Sports Network (Tom Turbiville, Tap Bentz) Nov. 28 10/9 11/14 vs. Ohio State L, 80-95 On The Aggies Tom Weston Classic, Cannon Event Center, Laie, Hawai’i • A&M freshman Anriel Howard set an NCAA Tournament record with 27 rebounds against Missouri State Dec. 4 12/11 vs. Hawai’i W, 82-41 • Two-time All-American Courtney Walker is six points away from A&M’s career scoring record Dec. 5 12/11 vs. -

Aggie Ring the Aggie Ring Is Rich in Symbolism and Tradition and Is Perhaps the Most TIMELINE Recognizable and Enduring Symbol of the Aggie Network

30 Campus Resources 32 Responsibilities to Texas A&M TABLE 33 Offices of the Dean of Student Life 34 The Association of Former Students 35 Aggie Card 35 Campus Ministry Association 36 Campus Safety 37 University Police Department OF 38 Career Center 39 Corps Housing 39 Department of Multicultural Services 39 Financial Aid 40 Health Promotion 40 Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender (GLBT) Resource Center CONTENTS 41 Off-Campus Student Services 41 International Student Services 42 Department of Residence Life 44 Student Assistance Services 2 Welcome 45 Student Business Services 2 Letter from the President 46 Student Conduct Office 3 Letter from the Vice President for Student Affairs 46 Student Counseling Service 3 Letter from Student Body President 47 Student Health Services 4 Academic Calendar 48 University Student Rules 6 Office of New Student & Family Programs 49 Step In, Stand Up 50 Transportation Services 50 Veteran Services & Resources 8 History & Traditions 51 Women’s Resource Center 10 Aggieland’s History 11 Aggieland Traditions 16 Aggie Yells 17 Aggie Songs 52 Aggie Involvement 18 Campus Lingo 54 Corps of Cadets 56 Class Councils 56 Fish Camp 57 ExCEL Program 20 Academic Success 57 Aggie Transition Camps 22 Academic Success Center 57 Venture Camps 23 Tips for Academic Success 58 Intercollegiate Athletics 24 Disability Services 59 Fraternity & Sorority Life 24 Add/Drop & Q-Drop 60 Memorial Student Center 25 Aggie Honor System Office 61 Instrumental Music 25 LAUNCH 61 Choral Music 26 Libraries 62 Recreational Sports 27 Study Abroad 64 Residential Housing Association 28 University Writing Center 64 Department of Student Activities 28 Texas A&M Information Technology 65 Student Government Association 29 Testing Services 65 Student Media 29 Office of Professional School Advising 66 Helpful Information WELCOME OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT Howdy! Welcome to Texas A&M University. -

Houston Aggie Website to Ensure You Don’T Miss a Minute of Houston Aggie News, Please Go to and Click on the “Update” Button Now

www.HoustonAgs.org | Fourth Quarter 2013 ® HOUSTON Keeping the Spirit AGGIEof Aggieland thanks graciasdankesalamat grazie tackmerci obrigado natick mahalo toda kiitosxie xie arigato Happy Holidays COMING SOON The New and Improved Houston Aggie Website To ensure you don’t miss a minute of Houston Aggie News, please go to www.HoustonAgs.org and click on the “update” button now. 45011_.indd 7 12/17/13 9:51 AM The Houston A&M Club is the largest association of former students in the world. HAMC is run by volunteers and funded entirely by donations. Contents Membership is FREE, but registration is required each year to ensure page 3 Howdy from the Houston A&M Club President that our records remain current. page 4 Spirit of An Aggie Entrepreneur www.HoustonAgs.org Fellow Students: A Collection of Aggie Poetry The HAMC is a tax-exempt, non-profit organization recognized under section 501(c)(3). Our Federal Tax ID# is 76-015741. page 5 HAMC Builds Bridge from College Station... 99 Bottles of Beer...Aggie Volunteers at iFest Houston Aggie, P.O. Box 27382 Houston, Texas 77227-7382 page 6 An Aggie Abroad: Ubud, Bali The Houston Aggie Magazine, published four times per year (in page 7 Muster March, June, September, and December), is the official publication of the HAMC and is free to all members. Opinions expressed are not page 8 Put a Bit of Aggieland in Your Next Event necessarily those of the HAMC or the editor. Content may not be reprinted without the permission of the author, artist, or editor. -

Federation of Texas A&M University Mothers' Clubs 2017-2018 Annual

Federation of Texas A&M University Mothers’ Clubs 2017-2018 Annual Report of Clubs Cindy DeWitt ’86, 4th VP Reports 2018-2019 [email protected] ~ 979-777-3832 AMARILLO Number of Members: 64 Donations to Texas A&M Organizations & Harvey Relief Fund: $1607.31 Total - $200 was given to the Mothers’ Club Library Endowment, $200 to Breakaway, $200 to Young Life & $200 to The Big Event. This fall, we sold umbrellas that had BTHO Harvey on them. The profit of $807.31 went to the TAMU Harvey Disaster Relief Fund. Scholarship Giving: We had drawings for six $100 book awards to the Barnes & Noble at the MSC when we had our summer social. We had drawings to give away a total of twelve $100 scholarships at our meetings and family dinner. Successful Fund Raiser: We sold Toot ‘N Totum Car Wash Tickets and Umbrellas that had BTHO Harvey on them. Special Events: In May, we held a social to welcome incoming freshman and transfer students and their parents to the A&M family. We had a panel of students their to answer questions about the NSC, registration, dorms, parking, etc. (we contacted panhandle high school counselors to get our invitation to the incoming students) In January, we had a dinner at Abuelo’s for our Aggie students home for Christmas break. This year’s guest speaker was Dr. Kyle Sparkman, a former yell leader. Memorable Programs: At our September meeting, we had a BBQ sandwich meal before the meeting to allow time for new and old members to get acquainted. -

New Student Conferences

2014 Freshman CONFERENCE CHECKLIST Conference Handbook ARE YOU READY FOR YOUR NEW STUDENT CONFERENCE? Students are expected to come to the NSC prepared. We encourage you to tear out this page to remind you of what you need to do New Student before your NSC. Before your New Student Conference, Conferences be sure to: newaggie.tamu.edu ❏ Make your NSC overnight accommodations. See page 5 in this book for details. ❏ Register any family members or guests who are attending the NSC with you. See page 4. ❏ Purchase an NSC parking permit and print out the receipt at the end of the purchasing process for use as a permit. Bring it with you to the conference, and place the printout on your dashboard. See page 6. ❏ Submit evidence of vaccination against bacterial meningitis. See page 8. ❏ Take your Math Placement Exam and Foreign Language Placement Exam, if applicable. See pages 9 and 10. ❏ Complete the Lab Safety Acknowledgment via the Howdy Portal. See page 10. ❏ Begin checking your TAMU email account as this is now the university’s primary official means of communicating with you. See below. ❏ Connect on Facebook and Twitter. “Like” the Facebook page “New Aggie” and follow us on Twitter @NSFPtamu for updates and reminders. More on back TEXAS A&M EMAIL As a confirmed new student, you now have a Texas A&M Email account. Your email address is your [email protected]. Your NetID is the same ID you use to log in to Howdy and the Applicant Information System. You should start checking your Texas A&M Email account regularly because important information will be sent there prior to your New Student Conference.