Egypt: 'Officially, You Do Not Exist' – Disappeared and Tortured in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter #9

Newsletter #9 Cairo, 6th January 2019 Ras Ghareb Wind Energy – Project Update RGWE team wishes a happy and successful Year 2019 to all our stakeholders and readers ! The project construction progress is close to 60% mark, still slightly ahead from the original plan. More than 1,500,000 manhours have been worked at site with our Health & Safety target of no Lost Time Incident being fulfilled. The works performed by Orascom Construction under the Civil Works and Electrical Systems Agreement (CWESA) are progressing ahead of schedule. More than 110 out of the 125 Wind Turbine foundations have been poured and the internal roads are almost completed. The construction of the site buildings is progressing and in particular the Control Room building is about to reach completion. The erection of the MV/HV electrical substation is proceeding ahead of schedule. The laying of the MV and fiber optics cables connecting the Wind Turbines to the substation is also progressing well. Pouring of the 100th foundation Oil filing of step-up transformer 1 Ras Ghareb Wind Energy S.A.E., Egyptian Joint Stock Company registered under Internal Investment System Commercial register number: 104490 – Tax Card: 540 – 931 - 810 Registered office: Unit 1418, Floor 14, Nile City, Southern Tower, Ramlet Boulaq, Cairo, Egypt Branch office: Sahara Building, Plot 227, Second Sector, Fifth Settlement, New Cairo, Egypt On the wind turbines erection side, Siemens Gamesa is progressing well with the assembly of Towers, Nacelles, Hubs and Blades with currently 29 out of 125 wind turbines erected. On road 01 several turbines are assembled: RGWE is also mobilizing in view of the early operations phase of the project. -

Egypt: Freedom on the Net 2017

FREEDOM ON THE NET 2017 Egypt 2016 2017 Population: 95.7 million Not Not Internet Freedom Status Internet Penetration 2016 (ITU): 39.2 percent Free Free Social Media/ICT Apps Blocked: Yes Obstacles to Access (0-25) 15 16 Political/Social Content Blocked: Yes Limits on Content (0-35) 15 18 Bloggers/ICT Users Arrested: Yes Violations of User Rights (0-40) 33 34 TOTAL* (0-100) 63 68 Press Freedom 2017 Status: Not Free * 0=most free, 100=least free Key Developments: June 2016 – May 2017 • More than 100 websites—including those of prominent news outlets and human rights organizations—were blocked by June 2017, with the figure rising to 434 by October (se Blocking and Filtering). • Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) services are restricted on most mobile connections, while repeated shutdowns of cell phone service affected residents of northern Sinai (Se Restrictions on Connectivity). • Parliament is reviewing a problematic cybercrime bill that could undermine internet freedom, and lawmakers separately proposed forcing social media users to register with the government and pay a monthly fee (see Legal Environment and Surveillance, Privacy, and Anonymity). • Mohamed Ramadan, a human rights lawyer, was sentenced to 10 years in prison and a 5-year ban on using the internet, in retaliation for his political speech online (see Prosecutions and Detentions for Online Activities). • Activists at seven human rights organizations on trial for receiving foreign funds were targeted in a massive spearphishing campaign by hackers seeking incriminating information about them (see Technical Attacks). 1 www.freedomonthenet.org Introduction FREEDOM EGYPT ON THE NET Obstacles to Access 2017 Introduction Availability and Ease of Access Internet freedom declined dramatically in 2017 after the government blocked dozens of critical news Restrictions on Connectivity sites and cracked down on encryption and circumvention tools. -

Greater Cairo Air Pollution Management and Climate Change Project

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Greater Cairo Air Pollution Management and Public Disclosure Authorized Climate Change Project ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK (ESMF) Prepared by: Integral Consult© Public Disclosure Authorized A Member of Environmental Alliance ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK (ESMF) Greater Cairo Air Pollution Management and Climate Change Project Integral Consult Cairo Office 2075 El Mearaj City, Ring Road, Maadi – Cairo - Egypt Phone +202 25204515 • Fax +202 25204514 Email : [email protected] Greater Cairo Air Pollution Management and Climate Change Project Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) ii Contributors to the Study Dr. Amr Osama, Integral Consult President Dr. Yasmine Kamal, Technical and Operations Manager Dr. Nermin Eltouny, Technical Team Lead Eng. Mai Ibrahim, Technical Team Lead Dr. Anan Mohamed, Social Development Consultant Eng. Fatma Adel, Senior Environmental Specialist Eng. Basma Sobhi, Senior Environmental Specialist Eng. Mustafa Adel, Environmental Specialist Eng. Lana Mahmoud, Environmental Specialist Greater Cairo Air Pollution Management and Climate Change Project Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ................................................................................................................... x List of Figures ................................................................................................................ xiii List of Acronyms -

Initial Considerations for the Creation of an Inter-Regional Industrial Hemp Value Chain Between Malawi and South Africa

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Lowitt, Sandy Working Paper Initial considerations for the creation of an inter- regional industrial hemp value chain between Malawi and South Africa WIDER Working Paper, No. 2020/23 Provided in Cooperation with: United Nations University (UNU), World Institute for Development Economics Research (WIDER) Suggested Citation: Lowitt, Sandy (2020) : Initial considerations for the creation of an inter- regional industrial hemp value chain between Malawi and South Africa, WIDER Working Paper, No. 2020/23, ISBN 978-92-9256-780-4, The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER), Helsinki, http://dx.doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2020/780-4 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/229247 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

How to Navigate Egypt's Enduring Human Rights Crisis

How to Navigate Egypt’s Enduring Human Rights Crisis BLUEPRINT FOR U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY January 2016 Human Rights First American ideals. Universal values. On human rights, the United States must be a beacon. Activists fighting for freedom around the globe continue to look to us for inspiration and count on us for support. Upholding human rights is not only a moral obligation; it’s a vital national interest. America is strongest when our policies and actions match our values. Human Rights First is an independent advocacy and action organization that challenges America to live up to its ideals. We believe American leadership is essential in the struggle for human rights so we press the U.S. government and private companies to respect human rights and the rule of law. When they don’t, we step in to demand reform, accountability and justice. Around the world, we work where we can best harness American influence to secure core freedoms. We know that it is not enough to expose and protest injustice, so we create the political environment and policy solutions necessary to ensure consistent respect for human rights. Whether we are protecting refugees, combating torture, or defending persecuted minorities, we focus not on making a point, but on making a difference. For over 30 years, we’ve built bipartisan coalitions and teamed up with frontline activists and lawyers to tackle issues that demand American leadership. Human Rights First is a nonprofit, nonpartisan international human rights organization based in New York and Washington D.C. To maintain our independence, we accept no government funding. -

Egypt Presidential Election Observation Report

EGYPT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OBSERVATION REPORT JULY 2014 This publication was produced by Democracy International, Inc., for the United States Agency for International Development through Cooperative Agreement No. 3263-A- 13-00002. Photographs in this report were taken by DI while conducting the mission. Democracy International, Inc. 7600 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 1010 Bethesda, MD 20814 Tel: +1.301.961.1660 www.democracyinternational.com EGYPT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OBSERVATION REPORT July 2014 Disclaimer This publication is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Democracy International, Inc. and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................ 4 MAP OF EGYPT .......................................................... I ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................. II DELEGATION MEMBERS ......................................... V ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ....................... X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 6 ABOUT DI .......................................................... 6 ABOUT THE MISSION ....................................... 7 METHODOLOGY .............................................. 8 BACKGROUND ........................................................ 10 TUMULT -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian Urban Exigencies: Space, Governance and Structures of Meaning in a Globalising Cairo A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Global Studies by Roberta Duffield Committee in charge: Professor Paul Amar, Chair Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse Assistant Professor Javiera Barandiarán Associate Professor Juan Campo June 2019 The thesis of Roberta Duffield is approved. ____________________________________________ Paul Amar, Committee Chair ____________________________________________ Jan Nederveen Pieterse ____________________________________________ Javiera Barandiarán ____________________________________________ Juan Campo June 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis committee at the University of California, Santa Barbara whose valuable direction, comments and advice informed this work: Professor Paul Amar, Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse, Professor Javiera Barandiarán and Professor Juan Campo, alongside the rest of the faculty and staff of UCSB’s Global Studies Department. Without their tireless work to promote the field of Global Studies and committed support for their students I would not have been able to complete this degree. I am also eternally grateful for the intellectual camaraderie and unending solidarity of my UCSB colleagues who helped me navigate Californian graduate school and come out the other side: Brett Aho, Amy Fallas, Tina Guirguis, Taylor Horton, Miguel Fuentes Carreño, Lena Köpell, Ashkon Molaei, Asutay Ozmen, Jonas Richter, Eugene Riordan, Luka Šterić, Heather Snay and Leila Zonouzi. I would especially also like to thank my friends in Cairo whose infinite humour, loyalty and love created the best dysfunctional family away from home I could ever ask for and encouraged me to enroll in graduate studies and complete this thesis: Miriam Afifiy, Eman El-Sherbiny, Felix Fallon, Peter Holslin, Emily Hudson, Raïs Jamodien and Thomas Pinney. -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

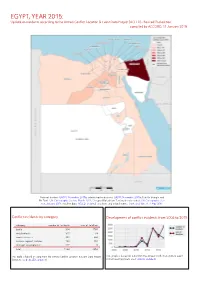

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Daring to Care Reflections on Egypt Before the Revolution and the Way Forward

THE ASSOCIATION OF INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVANTS IN EGYPT Daring To Care Reflections on Egypt Before The Revolution And The Way Forward Experts’ Views On The Problems That Have Been Facing Egypt Throughout The First Decade Of The Millennium And Ways To Solve Them Daring to Care i Daring to Care ii Daring to Care Daring to Care Reflections on Egypt before the revolution and the way forward A Publication of the Association of International Civil Servants (AFICS-Egypt) Registered under No.1723/2003 with Ministry of Solidarity iii Daring to Care First published in Egypt in 2011 A Publication of the Association of International Civil Servants (AFICS-Egypt) ILO Cairo Head Office 29, Taha Hussein st. Zamalek, Cairo Registered under No.1723/2003 with Ministry of Solidarity Copyright © AFICS-Egypt All rights reserved Printed in Egypt All articles and essays appearing in this book as appeared in Beyond - Ma’baed publication in English or Arabic between 2002 and 2010. Beyond is the English edition, appeared quarterly as a supplement in Al Ahram Weekly newspaper. Ma’baed magazine is its Arabic edition and was published independently by AFICS-Egypt. BEYOND-MA’BAED is a property of AFICS EGYPT No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without prior permission of AFICS Egypt. Printed in Egypt by Moody Graphic International Ltd. 7, Delta st. ,Dokki 12311, Giza, Egypt - www.moodygraphic.com iv Daring to Care To those who have continuously worked at stirring the conscience of Egypt, reminding her of her higher calling and better self. -

2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial

THE STRATEGIC URBAN DEVELOPMENT MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR A SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREATER CAIRO REGION IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT Final Report (Volume 2) 2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial area Commercial areas in GCR can be classified into three basic types: (i) the CBD; (ii) the sub-center which includes the mixed use for commercial/business and residential use; and (iii) major shopping malls such the large size commercial facilities in relatively new urban areas. The CBD is located in downtown areas, where there are mixed-use buildings that were established long ago and partly accommodate shops and stores. The major sub-centers in the main agglomeration are Shobra, Abasia, Zamalek, Heliopolis, Nasr city, Maadi in Cairo governorate and Mohandeseen, Dokki, Giza in Giza governorate. The recent trend following the mid-1990’s can been seen in the construction of shopping malls which are commercial complexes comprising a movie theater, restaurants, retail shops, and sufficient parking space or a parking building attached. These suburban shopping malls are mainly located in Nasr city, Heliopolis city, Maadi, Shobra, and Giza. Source: JICA study team Figure 2.5.3 Location of Major Commercial Areas in main agglomeration (2) Industrial area The following map shows location of concentration of industrial areas in Study area. There are seven industrial areas in NUCs, five industrial areas under governorates, and two public free zones in the study area. The number of registered factories is 13,483 with a total area of 76,297 ha. Among those registered factories, 3 % of factories can be categorized as large-scale which have an investment cost of more than LE10 million, or more than 500 employees. -

Production and Marketing Problems Facing Olive Farmers in North Sinai

Mansour et al. Bulletin of the National Research Centre (2019) 43:68 Bulletin of the National https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-019-0112-z Research Centre RESEARCH Open Access Production and marketing problems facing olive farmers in North Sinai Governorate, Egypt Tamer Gamal Ibrahim Mansour1* , Mohamed Abo El Azayem1, Nagwa El Agroudy1 and Salah Said Abd El-Ghani1,2 Abstract Background: Although North Sinai Governorate has a comparative advantage in the production of some crops as olive crop, which generates a distinct economic return, whether marketed locally or exported. This governorate occupies the twentieth place for the productivity of this crop in Egypt. The research aimed to identify the most important production and marketing problems facing olive farmers in North Sinai Governorate. Research data were collected through personal interviewing questionnaire with 100 respondents representing 25% of the total olive farmers at Meriah village from October to December 2015. Results: Results showed that there are many production and marketing problems faced by farmers. The most frequent of the production problems were the problem of increasing fertilizer prices (64% of the surveyed farmers), and the problem of irrigation water high salinity (52% of the respondents). Where the majority of the respondents mentioned that these problems are the most important productive problems they are facing, followed by problems of poor level of extension services (48%), high cost of irrigation wells (47%), difficulty in owning land (46%), and lack of agricultural mechanization (39%), while the most important marketing problems were the problem of the exploitation of traders (62%), the absence of agricultural marketing extension (59%), the high prices of trained labor to collect the crop (59%), and lack of olive presses present in the area (57%). -

Playing with Fire. the Muslim Brotherhood and the Egyptian

Playing with Fire.The Muslim Brotherhood and the Egyptian Leviathan Daniela Pioppi After the fall of Mubarak, the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) decided to act as a stabilising force, to abandon the street and to lend democratic legiti- macy to the political process designed by the army. The outcome of this strategy was that the MB was first ‘burned’ politically and then harshly repressed after having exhausted its stabilising role. The main mistakes the Brothers made were, first, to turn their back on several opportunities to spearhead the revolt by leading popular forces and, second, to keep their strategy for change gradualist and conservative, seeking compromises with parts of the former regime even though the turmoil and expectations in the country required a much bolder strategy. Keywords: Egypt, Muslim Brotherhood, Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, Arab Spring This article aims to analyse and evaluate the post-Mubarak politics of the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) in an attempt to explain its swift political parable from the heights of power to one of the worst waves of repression in the movement’s history. In order to do so, the analysis will start with the period before the ‘25th of January Revolution’. This is because current events cannot be correctly under- stood without moving beyond formal politics to the structural evolution of the Egyptian system of power before and after the 2011 uprising. In the second and third parts of this article, Egypt’s still unfinished ‘post-revolutionary’ political tran- sition is then examined. It is divided into two parts: 1) the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF)-led phase from February 2011 up to the presidential elections in summer 2012; and 2) the MB-led phase that ended with the military takeover in July 2013 and the ensuing violent crackdown on the Brotherhood.