Political Science 9600 Readings in Comparative Politics Course

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rights and Votes

1065.DOC 3/29/2012 5:23:12 PM Daryl J. Levinson Rights and Votes abstractT .T T This Article explores the functional similarities, residual differences, and interrelationships between rights and votes, both conceived as tools for protecting minorities (or other vulnerable groups) from the tyranny of majorities (or other dominant social and political actors). The Article starts from the simple idea that the interests of vulnerable groups in collective decisionmaking processes can be protected either by disallowing certain outcomes that would threaten those interests (using rights) or by enhancing the power of these groups within the decisionmaking process to enable them to protect their own interests (using votes). Recognizing that rights and votes can be functional substitutes for one another in this way, the Article proceeds to ask why, or under what circumstances, political and constitutional actors might prefer one to the other—or some combination of both. While the primary focus is on constitutional law and design, the Article shows that similar choices between rights and votes arise in many different areas of law, politics, and economic organization, including international law and governance, corporations, criminal justice, and labor and employment law. author.T T David Boies Professor of Law, New York University School of Law. Thanks to Gabriella Blum, Ryan Bubb, John Ferejohn, Barry Friedman, Heather Gerken, Ryan Goodman, Bernard Grofman, Don Herzog, Roderick Hills, Daniel Hulsebosch, Michael Klarman, Robert Keohane, Janos Kis, Douglas Laycock, Michael Levine, Dotan Oliar, Benjamin Sachs, Adam Samaha, Peter Schuck, Matthew Stephenson, and Adrian Vermeule, and to participants in workshops at Harvard Law School, New York University School of Law, and University of Virginia School of Law, for useful comments on drafts. -

Analyzing Change in International Politics: the New Institutionalism and the Interpretative Approach

Analyzing Change in International Politics: The New Institutionalism and the Interpretative Approach - Guest Lecture - Peter J. Katzenstein* 90/10 This discussion paper was presented as a guest lecture at the MPI für Gesellschaftsforschung, Köln, on April 5, 1990 Max-Planck-Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung Lothringer Str. 78 D-5000 Köln 1 Federal Republic of Germany MPIFG Discussion Paper 90/10 Telephone 0221/ 336050 ISSN 0933-5668 Fax 0221/ 3360555 November 1990 * Prof. Peter J. Katzenstein, Cornell University, Department of Government, McGraw Hall, Ithaca, N.Y. 14853, USA 2 MPIFG Discussion Paper 90/10 Abstract This paper argues that realism misinterprets change in the international system. Realism conceives of states as actors and international regimes as variables that affect national strategies. Alternatively, we can think of states as structures and regimes as part of the overall context in which interests are defined. States conceived as structures offer rich insights into the causes and consequences of international politics. And regimes conceived as a context in which interests are defined offer a broad perspective of the interaction between norms and interests in international politics. The paper concludes by suggesting that it may be time to forego an exclusive reliance on the Euro-centric, Western state system for the derivation of analytical categories. Instead we may benefit also from studying the historical experi- ence of Asian empires while developing analytical categories which may be useful for the analysis of current international developments. ***** In diesem Aufsatz wird argumentiert, daß der "realistische" Ansatz außenpo- litischer Theorie Wandel im internationalen System fehlinterpretiere. Dieser versteht Staaten als Akteure und internationale Regime als Variablen, die nationale Strategien beeinflussen. -

PSC 760R Proseminar in Comparative Politics Fall 2016

PSC 760R Proseminar in Comparative Politics Fall 2016 Professor: Office: Office Phone: Office Hours: Email: Course Description and Learning Outcomes Comparative politics is perhaps the broadest field of political science. This course will introduce students to the major theoretical approaches employed in comparative politics. The major debates and controversies in the field will be examined. Although some associate comparative politics with “the comparative method,” those conducting research in the area of comparative politics use a multitude of methodologies and pursue diverse topics. In this course, students will analyze and discuss the theoretical approaches and methods used in comparative politics. Course Requirements Class participation and attendance. Students must come to class prepared, having completed all of the required reading, and ready to actively discuss the material at hand. Each student must submit comments/questions on the assigned readings for six classes (not including the class you help facilitate). Please e-mail them to me by noon on the day of class. Students are expected to attend each class. Missing classes will have a deleterious effect on this portion of the grade. Arriving late, leaving early, or interrupting class with a phone or other electronic device will also result in a drop in the student’s grade. Students are not allowed to sleep, read newspapers or anything else, listen to headphones, TEXT, or talk to others during class. You must turn off all electronic devices during class. Any exceptions must be cleared with me in advance. Laptop computers and iPads are allowed for taking notes ONLY. I reserve the right to ban laptops, iPads, and so forth. -

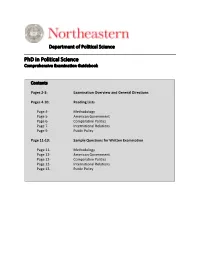

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

The Politics of Group Representation Quotas for Women and Minorities Worldwide Mona Lena Krook and Diana Z

The Politics of Group Representation Quotas for Women and Minorities Worldwide Mona Lena Krook and Diana Z. O’Brien In recent years a growing number of countries have established quotas to increase the representation of women and minorities in electoral politics. Policies for women exist in more than one hundred countries. Individual political parties have adopted many of these provisions, but more than half involve legal or constitutional reforms requiring that all parties select a certain proportion of female candidates.1 Policies for minorities are present in more than thirty countries.2 These measures typically set aside seats that other groups are ineligible to contest. Despite parallels in their forms and goals, empirical studies on quotas for each group have developed largely in iso- lation from one another. The absence of comparative analysis is striking, given that many normative arguments address women and minorities together. Further, scholars often generalize from the experiences of one group to make claims about the other. The intuition behind these analogies is that women and minorities have been similarly excluded based on ascriptive characteristics like sex and ethnicity. Concerned that these dynamics undermine basic democratic values of inclusion, many argue that the participation of these groups should be actively promoted as a means to reverse these historical trends. This article examines these assumptions to explore their leverage in explaining the quota policies implemented in national parliaments around the world. It begins by out- lining three normative arguments to justify such measures, which are transformed into three hypotheses for empirical investigation: (1) both women and minorities will re- ceive representational guarantees, (2) women or minorities will receive guarantees, and (3) women will receive guarantees in some countries, while minorities will receive them in others. -

Arend Lijphart and the 'New Institutionalism'

CSD Center for the Study of Democracy An Organized Research Unit University of California, Irvine www.democ.uci.edu March and Olsen (1984: 734) characterize a new institutionalist approach to politics that "emphasizes relative autonomy of political institutions, possibilities for inefficiency in history, and the importance of symbolic action to an understanding of politics." Among the other points they assert to be characteristic of this "new institutionalism" are the recognition that processes may be as important as outcomes (or even more important), and the recognition that preferences are not fixed and exogenous but may change as a function of political learning in a given institutional and historical context. However, in my view, there are three key problems with the March and Olsen synthesis. First, in looking for a common ground of belief among those who use the label "new institutionalism" for their work, March and Olsen are seeking to impose a unity of perspective on a set of figures who actually have little in common. March and Olsen (1984) lump together apples, oranges, and artichokes: neo-Marxists, symbolic interactionists, and learning theorists, all under their new institutionalist umbrella. They recognize that the ideas they ascribe to the new institutionalists are "not all mutually consistent. Indeed some of them seem mutually inconsistent" (March and Olsen, 1984: 738), but they slough over this paradox for the sake of typological neatness. Second, March and Olsen (1984) completely neglect another set of figures, those -

Toward a More Democratic Congress?

TOWARD A MORE DEMOCRATIC CONGRESS? OUR IMPERFECT DEMOCRATIC CONSTITUTION: THE CRITICS EXAMINED STEPHEN MACEDO* INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 609 I. SENATE MALAPPORTIONMENT AND POLITICAL EQUALITY................. 611 II. IN DEFENSE OF THE SENATE................................................................ 618 III. CONSENT AS A DEMOCRATIC VIRTUE ................................................. 620 IV. REDISTRICTING AND THE ELECTORAL COLLEGE REFORM? ................ 620 V. THE PROBLEM OF GRIDLOCK, MINORITY VETOES, AND STATUS- QUO BIAS: UNCLOGGING THE CHANNELS OF POLITICAL CHANGE?.... 622 CONCLUSION................................................................................................... 627 INTRODUCTION There is much to admire in the work of those recent scholars of constitutional reform – including Sanford Levinson, Larry Sabato, and prior to them, Robert Dahl – who propose to reinvigorate our democracy by “correcting” and “revitalizing” our Constitution. They are right to warn that “Constitution worship” should not supplant critical thinking and sober assessment. There is no doubt that our 220-year-old founding charter – itself the product of compromise and consensus, and not only scholarly musing – could be improved upon. Dahl points out that in 1787, “[h]istory had produced no truly relevant models of representative government on the scale the United States had already attained, not to mention the scale it would reach in years to come.”1 Political science has since progressed; as Dahl also observes, none of us “would hire an electrician equipped only with Franklin’s knowledge to do our wiring.”2 But our political plumbing is just as archaic. I, too, have participated in efforts to assess the state of our democracy, and co-authored a work that offers recommendations, some of which overlap with * Laurance S. Rockefeller Professor of Politics and the University Center for Human Values; Director of the University Center for Human Values, Princeton University. -

PSC13 Introduction to Comparative Politics Course Description

PSC13 Introduction to Comparative Politics Instructor: Richard S. Conley, PhD Office hours: TBA Email: [email protected] Teaching Assistant: Li Shao Course Description This course introduces students to the discipline of comparative politics, a subfield in political science. Students of comparative politics study politics in countries around the world. Our course will focus on several important themes in the subfield including the science and the art of comparative politics, ideology and culture, political development, democracy and democratization, and the political economy of development. The approach in the class will be global in three senses of the term: 1) it provides broad coverage with select cases in Europe, Asia, North and South America, the Middle East, and Africa, 2) it offers conceptual comprehensiveness, and 3) it promotes critical thinking. Learning Objectives: The general objective of this course is to increase the students knowledge of political realities all aver the world. Students will learn the many ways governments operate and the various ways people behave in political life. By the end of the term students should be able to: accurately describe political life in select countries in all of the world’s geographic regions; show a familiarity with a wide range of substantive issues in comparative politics and be able to discuss them critically; demonstrate mastery of the main theoretical and analytical approaches to the study of comparative politics. Required Text Mark Kesselmen, Joel Krieger, William Joseph (eds.). Introduction to Comparative Politics (6th Edition, 2012). Available as an Electronic Book. ISBN-10: 1111831823; ISBN-13: 978- 1111831820. Other texts will be available as electronic files Course Hours The course has 26 class sessions in total. -

Theda Skocpol

NAMING THE PROBLEM What It Will Take to Counter Extremism and Engage Americans in the Fight against Global Warming Theda Skocpol Harvard University January 2013 Prepared for the Symposium on THE POLITICS OF AMERICA’S FIGHT AGAINST GLOBAL WARMING Co-sponsored by the Columbia School of Journalism and the Scholars Strategy Network February 14, 2013, 4-6 pm Tsai Auditorium, Harvard University CONTENTS Making Sense of the Cap and Trade Failure Beyond Easy Answers Did the Economic Downturn Do It? Did Obama Fail to Lead? An Anatomy of Two Reform Campaigns A Regulated Market Approach to Health Reform Harnessing Market Forces to Mitigate Global Warming New Investments in Coalition-Building and Political Capabilities HCAN on the Left Edge of the Possible Climate Reformers Invest in Insider Bargains and Media Ads Outflanked by Extremists The Roots of GOP Opposition Climate Change Denial The Pivotal Battle for Public Opinion in 2006 and 2007 The Tea Party Seals the Deal ii What Can Be Learned? Environmentalists Diagnose the Causes of Death Where Should Philanthropic Money Go? The Politics Next Time Yearning for an Easy Way New Kinds of Insider Deals? Are Market Forces Enough? What Kind of Politics? Using Policy Goals to Build a Broader Coalition The Challenge Named iii “I can’t work on a problem if I cannot name it.” The complaint was registered gently, almost as a musing after-thought at the end of a June 2012 interview I conducted by telephone with one of the nation’s prominent environmental leaders. My interlocutor had played a major role in efforts to get Congress to pass “cap and trade” legislation during 2009 and 2010. -

Why Arab States Lag in Gender Equality

MECCA OR OIL? NORRIS 2/16/2011 1:40 PM Mecca or oil? Why Arab states lag in gender equality Pippa Norris (Harvard University and the University of Sydney) McGuire Lecturer in Comparative Politics Visiting Professor of Government and IR John F. Kennedy School of Government The University of Sydney Harvard University Department of Government & IR Cambridge, MA 02138 NSW, 2006 [email protected] [email protected] www.pippanorris.com www.arts.sydney.edu.au Synopsis: Why do Arab states continue to lag behind the rest of the world in gender equality? Cultural values and structural resources offer two alternative perspectives. Drawing upon Inglehart’s modernization theory, cultural accounts emphasize that disparities are reinforced by the predominance of traditional attitudes towards the roles of women and men in developing societies, combined with the strength of religiosity in the Middle East and North Africa (Inglehart and Norris 2003, Norris and Inglehart 2004). An alternative structural view is presented by the ‘petroleum patriarchy’ thesis, developed by Michael Ross (2008), which claims that oil‐rich economies directly limit the role of women in the paid workforce and thus also (indirectly) restrict women’s representation in parliament. To consider these issues, Part I outlines these theoretical arguments. Part II discusses the most appropriate research design used to analyze the evidence. Part III presents multilevel models using the World Values Survey 1995‐2005 in 75‐83 societies demonstrating that religious traditions have a greater influence on attitudes towards gender equality and sexual liberalization than either labor force participation or oil rents. Part IV then demonstrates the impact of these cultural attitudes on the proportion of women in legislative and ministerial office. -

Semester at Sea Course Syllabus

Democratization and Modernization: Concepts, Issues, and Approaches SEMESTER AT SEA COURSE SYLLABUS Voyage: Spring 2013 Discipline: Political Science PLCP 3500: Democratization and Modernization: Concepts, Issues, and Approaches Division: Upper division Faculty Name: Tao XIE Pre-requisites: This course has no pre-requisites. However, intellectual curiosity in and prior exposure (academic or otherwise) to politics and history of non-U.S. countries, as well as knowledge about U.S. foreign policy, would be quite useful. COURSE DESCRIPTION This is an upper-level political science course that examines the major concepts, issues, and approaches in scholarly research on democratization and modernization. Given the nature of the Semester at Sea program, this course pay special attention to processes of democratization and modernization in countries located along the route, as well as topics that are highly relevant for these countries. As the ship departs the U.S., the oldest democracy in the world, the course starts with discussions about democracy, including how to conceptualize democracy, the relationship between economic development and democracy, and the pros and cons of different forms of democratic governance. When the ship approaches Japan, we will shift attention to Japanese politics and U.S.-Japan relations. We will take a brief look at the cultural underpinnings of the Japanese democracy, as well as the major issues in U.S.-Japan relations. As the ship departs Kobe, we will spend three classes on China, the largest (in terms of population, territory, and economy) country on the route. We first address the rise of China, particularly its implications for regional and international security. -

Measuring the Research Productivity of Political Science Departments Using Google Scholar

The Profession ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Measuring the Research Productivity of Political Science Departments Using Google Scholar Michael Peress, SUNY–Stony Brook ABSTRACT This article develops a number of measures of the research productivity of politi- cal science departments using data collected from Google Scholar. Departments are ranked in terms of citations to articles published by faculty, citations to articles recently published by faculty, impact factors of journals in which faculty published, and number of top pub- lications in which faculty published. Results are presented in aggregate terms and on a per-faculty basis. he most widely used measure of the quality of of search results, from which I identified publications authored political science departments is the US News and by that faculty member, the journal in which the publication World Report ranking. It is based on a survey sent appeared (if applicable), and the number of citations to that to political science department heads and direc- article or book. tors of graduate studies. Respondents are asked to I constructed four measures for each faculty member. First, Trate other political science departments on a 1-to-5 scale; their I calculated the total number of citations. This can be