The Rise and Fall of Violent Crime in America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Educational and Labor Market Outcomes of Ghanaian, Liberian

Educational and labor market outcomes of Ghanaian, Liberian, Nigerian, and Sierra Leonean Americans, 2010–2017 Ernesto F. L. Amaral Texas A&M University, [email protected] Arthur Sakamoto Texas A&M University, [email protected] Courtney Nelson Sweet Briar College, [email protected] Sharron X. Wang Texas A&M University, [email protected] Abstract Research on immigrant African Americans is slowly increasing, but more studies are needed particularly in regard to specific ethnic groups and their second-generation offspring. We investigate socioeconomic outcomes among second-generation African Americans focusing on those from English-speaking countries in West Africa including Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone (GLNS). We use data from the 2010–2017 Current Population Surveys to impute ethnicity on the basis of country of parental birth. Results for generalized ordered logit models for men reveal that GLNS are more likely to have a bachelor’s degree than third-plus-generation whites, third-plus-generation blacks, second-generation whites, other-second-generation blacks, but not second-generation Asians. Among women, GLNS are more likely to have a bachelor’s degree than all of these groups. OLS estimates of regressions of wages show that net of education, age, marital status, and having children, GLNS men are not disadvantaged relative to third-plus-generation whites in contrast to the disadvantage of 7 percent for other-second- generation blacks and 18 percent for third-plus-generation blacks. In regard to women, neither GLNS nor other-second-generation blacks are disadvantaged relative to third-plus-generation whites in contrast to the disadvantage of 8 percent for third-plus-generation blacks. -

Race-Class Interactions in Stereotyping

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1998 Race-Class Interactions in Stereotyping Claudine Hoffman Truong Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Psychology at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Truong, Claudine Hoffman, "Race-Class Interactions in Stereotyping" (1998). Masters Theses. 1766. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1766 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is receiving a number of request from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow these to be copied . PLEASE SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university or the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. I / 2 1 /fa Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University NOT allow my thesis to be reproduced because: Author's Signature Date thesis4.f orm Race-class Interactions in Stereotyping (TITLE) BY Claudine Hoffman Truong J lf 7~ - THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILIJNOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON. -

Narratives of Interiority: Black Lives in the U.S. Capital, 1919 - 1942

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2015 Narratives of Interiority: Black Lives in the U.S. Capital, 1919 - 1942 Paula C. Austin Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/843 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] NARRATIVES OF INTERIORITY: BLACK LIVES IN THE U.S. CAPITAL, 1919 – 1942 by PAULA C. AUSTIN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 ©2015 Paula C. Austin All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________ ____________________________ Date Herman L. Bennett, Chair of Examining Committee ________________ _____________________________ Date Helena Rosenblatt, Executive Office Gunja SenGupta Clarence Taylor Robert Reid Pharr Michele Mitchell Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract NARRATIVES OF INTERIORITY: BLACK LIVES IN THE U.S. CAPITAL, 1919 – 1942 by PAULA C. AUSTIN Advisor: Professor Herman L. Bennett This dissertation constructs a social and intellectual history of poor and working class African Americans in the interwar period in Washington, D.C. Although the advent of social history shifted scholarly emphasis onto the “ninety-nine percent,” many scholars have framed black history as the story of either the educated, uplifted and accomplished elite, or of a culturally depressed monolithic urban mass in need of the alleviation of structural obstacles to advancement. -

N O P Q R S T U V W X

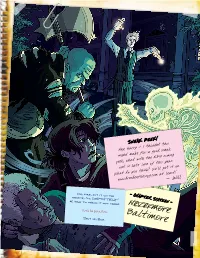

n o p q r s t u SNEAK PEEK! hey, harry — i thought this v might make for a good sneak peek, what with the RPG coming out in late June of this year. What do you think? We’ll put it on w www.dresdenfilesrpg.com at least! — Will Oh, sure, put it on the website, I’ll DEFINITELY x be able to check it out there. - Chapter Sixteen - - Don’t be pissy, Boss. n-evermore y Shut up, Bob. Baltimore z a nevermore/Baltimore sector. Financial services, education, tourism, Who Am I? and health services are dominating. Johns Hi. I’m Davian Campbell, a grad student b Hopkins is currently the biggest employer (not at the University of Chicago and one of the to mention a huge landowner), where it used translation: Alphas. Billy asked me to write up some- i helped to be Bethlehem Steel. Unemployment is high. thing about Baltimore for this game he’s Lots of folks are unhappy. Davian move writing. I guess he figured since I grew up Climate: They don’t get much snow in last august. there, I’d know it. I tried to tell him that c I haven’t lived there for years, and that Baltimore—two, maybe three times a year we 50 boxes of get a couple of inches. When that happens, books = a between patrolling, trying to finish my thesis, and our weekly game session, I don’t the entire town goes freaking loco. Stay off the favor or two. have time for this stuff. -

105318NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. " - ~"'~ t . ~.J-" .. HEROIN AND COCAINE 1'RAFFICKING AND RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN INTRAVENOUS USE AND ~IDS (NEW YORK) = HEARING BEFORE THE SELEOT OOI\fMITTEE ON NAROOTIOS ABUSE AND OONTROL HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES NINETY-NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 26, 1985 Printed for the use of the Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control ~ SCNAC-99-1-6 • < ~ ~ , .' ,.~ .. ~ , ~ , ~ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1986 ........ r sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office • U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 ~--------~------------------- , , SELECT COMMITTEE ON NARCOTICS ABUSE AND CONTROL (99th Congress) CHARLES B. RANGEL, New York, Chairman PETER W. RODINO, JR., New Jersey BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, New York FORTNEY H. (PETE) STARK, California LAWRENCE COUGHLIN, Pennsylvania JAMES H. SCHEUER, New York E. CLAY SHAW, JR., Florida CARDISS COLLINS, Illinois MICHAEL G. OXLEY, Ohio DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii STAN PARRIS, Virginia FRANK J. GUARINI, New Jersey GENE CHAPPlE, California ROBERT T. MATSm, California DUNCAN HUNTER, California DANTE B. FASCELL, Florida JOSEPH J. DIOGUARDI, New York WALTER E. FAUNTROY, District of MICHAEL L. STRANG, Colorado Columbia JOHN G. ROWLAND, C<lnnecticut WILLIAM J. HUGHES, New Jersey MEL LEVINE, California SOLOMON P. ORTIZ, Texas LAWRENCE J. SMITH, Florida EDOLPHUS "ED" TOWNS, New York COMMITl'EE STAFF .JOHN T, CUSAC.K, Chief of Staff Ewo'IT A. BROWN, Minority Staff Director (II) 105318 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stat?d in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the Nalional Institute of Justice. -

Chapter One: Postwar Resentment and the Invention of Middle America 10

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff Doctor of Philosophy ________________________________________ Timothy Melley, Director ________________________________________ C. Barry Chabot, Reader ________________________________________ Whitney Womack Smith, Reader ________________________________________ Marguerite S. Shaffer, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT TALES FROM THE SILENT MAJORITY: CONSERVATIVE POPULISM AND THE INVENTION OF MIDDLE AMERICA by Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff In this dissertation I show how the conservative movement lured the white working class out of the Democratic New Deal Coalition and into the Republican Majority. I argue that this political transformation was accomplished in part by what I call the "invention" of Middle America. Using such cultural representations as mainstream print media, literature, and film, conservatives successfully exploited what came to be known as the Social Issue and constructed "Liberalism" as effeminate, impractical, and elitist. Chapter One charts the rise of conservative populism and Middle America against the backdrop of 1960s social upheaval. I stress the importance of backlash and resentment to Richard Nixon's ascendancy to the Presidency, describe strategies employed by the conservative movement to win majority status for the GOP, and explore the conflict between this goal and the will to ideological purity. In Chapter Two I read Rabbit Redux as John Updike's attempt to model the racial education of a conservative Middle American, Harry "Rabbit" Angstrom, in "teach-in" scenes that reflect the conflict between the social conservative and Eastern Liberal within the author's psyche. I conclude that this conflict undermines the project and, despite laudable intentions, Updike perpetuates caricatures of the Left and hastens Middle America's rejection of Liberalism. -

JENSEN-THESIS-2018.Pdf (2.291Mb)

CONSUMPTION PATTERNS AND GROCERY PURCHASE DECISIONS AMONG MIDDLE AND WORKING CLASS FAMILIES IN SHREVEPORT, LOUISIANA _____________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Sociology Sam Houston State University _____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts _____________ by Kimberly Curry Jensen December, 2018 CONSUMPTION PATTERNS AND GROCERY PURCHASE DECISIONS AMONG MIDDLE AND WORKING CLASS FAMILIES IN SHREVEPORT, LOUISIANA by Kimberly Curry Jensen ______________ APPROVED: Karen Douglas, PhD Thesis Director Emily Cabaniss, PhD Committee Member Maki Hatanaka, PhD Committee Member Abbey Zink, PhD Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Bernadette Palombo, my dear friend and mentor, who is missed beyond words. “A good teacher is like a candle, it consumes itself to light the way to others.” - Mustafa Kemal Ataurk iii ABSTRACT Jensen, Kimberly Curry, Consumption patterns and grocery purchase decisions among middle and working class families in Shreveport, Louisiana. Master of Arts (Sociology), December, 2018, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, Texas. Extensive academic literature supports the finding that one’s socioeconomic status has significant influence on the food consumption patterns of individuals and families. Further, the link between diet and disease has been well established. However, not all states are equal when it comes to health and diet. The southern states, and more specifically individuals who consume a southern diet high in saturated fat, sugar, and salt, have much higher incidences of heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and other dietary influenced health conditions. To better understand the decisions people make at the grocery store, this thesis explores the grocery shopping decisions for low and middle income residents in four different neighborhoods in Shreveport, Louisiana. -

Gang Takedowns in the De Blasio Era

GANG TAKEDOWNS IN The Dangers of THE DE BLASIO ERA: ‘Precision Policing’ By JOSMAR TRUJILLO and ALEX S. VITALE TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. About & Acknowledgement . 1 2. Introduction . 2. 3. Gang Raids . .4 4. Database . 6 5. SIDEBAR: Inventing gangs . .11 6. Consequences of Gang Labeling . 13 i. Harassment, Hyper-Policing ii. Enhanced Bail iii. Indictments, Trials & Plea Deals iii. Employment Issues iv. Housing v. Deportation Risks 7. SIDEBAR: School Policing . 21 8. Focused Deterrence . 22 9. Prosecutor profile: Cyrus Vance Jr. 24 10. Action spotlight: Legal Aid’s FOIL Campaign . 28 11. Conclusion/Recommendations. 29 2019 New York City Gang Policing Report | 3 ABOUT THE POLICING AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS SOCIAL JUSTICE PROJECT This report was compiled and edited by Josmar Trujillo AT BROOKLYN COLLEGE and Professor Alex Vitale from The Policing and Social Justice Project at Brooklyn College. Additional research The Policing and Social Justice Project at Brooklyn support was provided by Amy Martinez. College is an effort of faculty, students and community researchers that offers support in dismantling harmful Insights from interviews of people directly impacted policing practices. Over the past three years, the by gang policing, including public housing residents, Project has helped to support actions, convenings, inspired and spearheaded this report. In many and community events to drive public education ways, this report is a reflection of the brave voices of and advocacy against the New York City Police community members and family members including Department’s gang policing tactics, including its so- Taylonn Murphy Sr., Darlene Murray, Diane Pippen, called gang database. Shaniqua Williams, Afrika Owes, Kraig Lewis, mothers from the Bronx120 case, and many more. -

The Carceral State and the Crucible of Black Politics: an Urban History of the Rockefeller Drug Laws1

Studies in American Political Development, 27 (April 2013), 14–35. ISSN 0898-588X/13 doi:10.1017/S0898588X13000011 # Cambridge University Press 2013 The Carceral State and the Crucible of Black Politics: An Urban History of the Rockefeller Drug Laws1 Michael Javen Fortner, Rutgers University-Camden While scholars have illuminated the effects of mass incarceration, the origins of the criminal justice policies that produced these outcomes remain unclear. Many explanations obscure as much as they reveal—in great measure because they either ignore or minimize the consequences of crime. Emphasizing the exploitation of white fears, the construction of black criminality, or the political strategies of Republican political elites, prevailing theories ignore black crime victims. In order to excavate the historical roots of the modern carceral state, this study traces the development of New York State’s Rockefeller drug laws. Rather than beginning in Albany, this history focuses on Harlem, a community hit hardest by rising crime rates and drug addiction. Drawing upon a variety of primary sources, this study traces how African American activists framed and negotiated the incipient drug problem in their neighborhoods and interrogates the policy prescriptions they attached to indigenously con- structed frames. It describes how middle-class African Americans facing the material threats of crime and crime-related problems drew upon the moral content of indigenous class categories to understand these threats and develop policy prescriptions. It reveals how the black middle class shaped the development of this punitive policy and played a crucial role in the development of mass incarceration. The United States is exceptional in the most peculiar whites, and Hispanics are incarcerated at almost way. -

Enhancing Parole Reentry and Public Safety in Upper Manhattan

Upper Manhattan Reentry Task Force Enhancing Parole Reentry and Public Safety in Upper Manhattan A Strategic Plan Harlem Community Justice Center 170 East 121 st Street New York, NY 10035 www.courtinnovation.org 1 Acknowledgements The Harlem Community Task Force would like to acknowledge the generous contributions of many individuals who helped bring this strategic plan and accompanying needs assessment to life. The Upper Manhattan Reentry Task Force is composed of the following individuals, all of whom have shown their dedication to promoting greater public safety and improved success for those returning to New York communities from prison or jail: Patricia Brown , Assistant Commissioner for Forensic Behavioral Health Services, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Sharon Davis , Addictions Program Specialist II, Bureau of Criminal Justice Services, New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services Charlene Fletcher , Manager of Criminal Justice Programs, The Doe Fund Leroy Frazer, Jr. , Executive Assistant District Attorney, Governmental Affairs and Community Relations, New York County District Attorney's Office Lynn Goodman , Statewide Director of Re-Entry Services, New York State Division of Parole Police Officer Kevin Grogan , New York Police Department Richard Levy , First Deputy Commissioner, New York City Department of Probation Glenn Martin , Vice President of Development and Public Affairs, The Fortune Society Sheila Mashack , Deputy Director, Greenhope Services for Women, Inc. George McDonald -

“Absolutely Sort of Normal”: the Common Origins of the War on Poverty at Home and Abroad, 1961-1965

“ABSOLUTELY SORT OF NORMAL”: THE COMMON ORIGINS OF THE WAR ON POVERTY AT HOME AND ABROAD, 1961-1965 by DANIEL VICTOR AKSAMIT B.A., UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA, 2005 M.A., KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY, 2009 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2014 Abstract Scholars identify the early 1960s as the moment when Americans rediscovered poverty – as the time when Presidents, policymakers, and the public shifted their attention away from celebrating the affluence of the 1950s and toward directly helping poor people within the culture of poverty through major federal programs such as the Peace Corps and Job Corps. This dissertation argues that this moment should not be viewed as a rediscovery of poverty by Americans. Rather, it should be viewed as a paradigm shift that conceptually unified the understanding of both foreign and domestic privation within the concept of a culture of poverty. A culture of poverty equally hindered poor people all around the world, resulting in widespread illiteracy in India and juvenile delinquency in Indianapolis. Policymakers defined poverty less by employment rate or location (rural poverty in Ghana versus inner-city poverty in New York) and more by the cultural values of the poor people (apathy toward change, disdain for education, lack of planning for the future, and desire for immediate gratification). In a sense, the poor person who lived in the Philippines and the one who lived in Philadelphia became one. They suffered from the same cultural limitations and could be helped through the same remedy. -

Organised Crime on the Cape Flats 35

Andre Standing i Organised crime A study from the Cape Flats BY ANDRE STANDING This publication was made possible through the generous funding of the Open Sociey Foundation i ii Contents www.issafrica.org @ 2006, Institute for Security Studies All rights reserved Copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in the Institute for Security Studies, and no part may be reproduced in whole or part without the express permission, in writing, of both the author and the publishers. The opinions expressed in this book do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute, its Trustees, members of the ISS Council, or donors. Authors contribute to ISS publications in their personal capacity. ISBN: 1-920114-09-2 First published by the Institute for Security Studies PO Box 1787, Brooklyn Square 0075 Pretoria, South Africa Cover photo: Benny Gool/Oryx Media Productions/africanpictures.net Cover: Page Arts cc Printers: Tandym Print Andre Standing iii Acknowledgements This book was commissioned by the Institute for Security Studies through a grant provided by the Open Society Foundation. I have been fortunate to work from the Cape Town office of the ISS for the past few years. The director of the ISS in Cape Town, Peter Gastrow, has been exceptionally supportive and, dare I say it, patient in waiting for the final publication. Friends and colleagues at the ISS who have helped provide a warm and stimulating work environment include Nobuntu Mtwa, Pilisa Gaushe, Charles Goredema, Annette Hubschle, Trucia Reddy, Andile Sokomani, Mpho Mashaba, Nozuko Maphazi and Hennie van Vuuren. In writing this book I have been extremely fortunate to have help and guidance from John Lea, who I owe much to over the years.