An Analysis of Q-Sorts Measuring Announcer Skill ~ - Usefulness As Perceived by Managers of Live and Automated Radio Stations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P85959 the E. W. Scripps Company 10K 2017 V1

2016 ANNUAL REPORT FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Operating Revenues Operating Revenues By Segment Continuing Operations Continuing Operations (Dollars in millions) $1000 Syndication and other Digital 1% Radio 7% $750 7% $500 $250 $716 $943 $499 85% Television $0 2014 2015 2016 2016 Operating Results – Continuing Operations 2014 2015 2016 (Dollars in millions) Consolidated Operating revenues............................................. $499 $716 $943 Operating income....................................................... 26 (83) 127 Net income (loss)................................................ 9.5 (67) 67 Television Segment operating revenues............................... 467 610 802 [ Radio Segment operating revenues............................... – 59 71 [ M Digital Segment operating revenues............................... 23 39 62 Segment loss....................................................... (23) (17) (16) Syndication and other Segment operating revenues............................... 9 8 8 Segment loss....................................................... (1.5) (1.1) (0.8) LETTER TO SHAREHOLDERS To our shareholders: From the vantage point of spring 2017, I can see behind us a year when our television division delivered record revenue, driven by more than $100 million of political advertising revenue and a 50 percent increase in fees we receive from cable and satellite operators who include our TV stations in their packages. From this same vantage point, I can see ahead to a year when local broadcasters’ optimism already has been lifted by the promised tailwinds of the advancement of next-gen television transmission standard ATSC 3.0 as well as further increases in the value of our content as represented by rising rates for the retransmission of our stations. At Scripps, 2017 also brings the promise of new leadership. After nearly 18 years as a member of the senior leadership team here at Scripps — including nine as CEO — I will retire from the role of president and CEO later this year, retaining the job of chairman of the board. -

Convention 2005: Largest Participation Ever the OAB Convention 2005 Set an All-Time Record for the Number of People Who Participated in the Event

Volume 18 – No. 1 Spring 2005 www.oabok.org Convention 2005: Largest Participation Ever The OAB Convention 2005 set an all-time record for the number of people who participated in the event. Friday’s attendance alone topped 500 with over 150 students and professors, 200 broadcasters in the sales sessions, an estimated 50 in the engineering conference, general registrants, exhibits, and 140 at the Hall of Fame dinner. Saturday’s sessions were well attended but did not reach those numbers with 125 at the Congressional luncheon and 240 attending the Saturday night awards dinner. The Tulsa Renaissance Hotel proved to be an ideal setting for the event and large attendance. The Friday morning session kicked off to a packed room as Merritt Mattson provided a wealth of infor- mation and insight on “The Other Side of the Yellow Page Story.” Former Governor Frank Keating entertained the crowd at the Student Appreciation luncheon with his great sense of humor and provided an inspirational message to the students. The 170+ attending the afternoon session on “Cable Advertising” gave Katz TV’s Rob Russo high marks June 9 Foundation Golf for his lively presentation. Scramble at Oak Tree Highlighting the day’s activities was the Hall of Fame dinner induct- ing John David, Don Wallace, Dick Schmitz and John Erling. Get ready to tee Introducing the honorees were Ken Greenwood for John David, up for the Educa- Ronnie Kaye for Don Wallace, Clayton Vaughn introducing Dick tion Foundation Schmitz, and former Governor Keating presenting John Erling. Golf Scramble First up on Saturday was the FCC’s Roy Stew- at Oak Tree in art providing an insight into some of the cur- Edmond on June rent issues and the new Chairman. -

S Application for an Order Finding the D

APSC FILED Time: 9/28/2018 3:53:22 PM: Recvd 9/28/2018 3:52:47 PM: Docket 16-060-U-Doc. 110 BEFORE THE ARKANSAS PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION IN THE MATTER OF ENTERGY ) ARKANSAS, INC.’S APPLICATION FOR ) AN ORDER FINDING THE DEPLOYMENT ) DOCKET NO. 16-060-U OF ADVANCED METERING ) INFRASTRUCTURE TO BE IN THE ) PUBLIC INTEREST AND EXEMPTION ) FROM CERTAIN APPLICABLE RULES JOINT MOTION TO APPROVE ADVANCED METERING INFRASTRUCTURE CUSTOMER EDUCATION PLAN FOR ENTERGY ARKANSAS, INC. Come now Entergy Arkansas, Inc. (“EAI” or the “Company”); the General Staff (“Staff”) of the Arkansas Public Service Commission (“APSC” or the “Commission”); and the Consumer Utilities Rate Advocacy Division of the Attorney General’s Office (“AG”) (hereinafter collectively, the “Settling Parties”), and for their Joint Motion (“Joint Motion”) to Approve the Advanced Metering Infrastructure Customer Education Plan for Entergy Arkansas, Inc. (“Customer Education Plan”) state as follows: 1. On August 11, 2017, the Settling Parties filed a Joint Motion to Approve Settlement Agreement (the “Agreement”) to inform the Commission that they had reached agreement on all issues in Docket No. 16-060-U. The Agreement set forth various commitments made by the Company pursuant to which Staff and the AG support that EAI’s deployment of Advanced Metering Infrastructure (“AMI”) is in the public interest. 2. On October 30, 2017, the Commission issued Order No. 8 finding that the Agreement and EAI’s deployment of AMI are in the public interest. The 1 APSC FILED Time: 9/28/2018 3:53:22 PM: Recvd 9/28/2018 3:52:47 PM: Docket 16-060-U-Doc. -

Grow Your Business with Us!

GROW YOUR BUSINESS WITH US! 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ▪ Where We’re Located Pg.3 ▪ Our Stations Pgs. 4-25 ▪ Our Jocks Pg. 26 ▪ Why We’re Awesome Pgs. 27-31 ▪ The Power of Radio Pgs. 32-35 ▪ Our Digital Products Pgs. 36-40 ▪ Our Sales Team Pg. 41 2 JONESBORO RADIO GROUP 314 Union St. Jonesboro, AR 72401 (870) 933-8800 President and General Manager: Trey Stafford General Sales Manager and Station Manager: Christie Matthews Operations Manager: Rob West Business Manager: Karen Hawes 3 COVERAGE MAP 50,000 Watts 100.5 The Eagle 25,000 Watts 104.9 The Fox and Mix 106.3 Metro Stations Hot 107.5, EZ 92.7, and 98.5 The Outlaw 4 Call letters: KDXY-FM/HD Branding: 104.9 The Fox Dial Position: 104.9 FM and 104.9 HD-1 Tagline: This is FOX Country! Format: Country Website: www.thefox1049.com Primary Focus: Adults 25-54 Core Artists: Carrie Underwood, Chris Stapleton, Luke Bryan, Jason Aldean, Thomas Rhett 5 Stafford and Frigo in the Morning with Trey Stafford and Jim Frigo 5 a.m. to 10 a.m. Fox at Work with Christie Matthews 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Afternoon Drive with Rob West 2 p.m. to 7 p.m. Fox Country Nights with Brady Dowler 7 p.m. to Midnight CMT After Midnight with Cody Allen and Crew Midnight to 5 a.m. Country Countdown with Lon Helton Sundays, 7 a.m. to 10 a.m. 6 DEMOS FOR 104.9 THE FOX AGE GENDER 22% 18% 19% 16% 15% 36% Sources: 9% 64% Google Analytics; KDXY-FM – The Fox 104.9; Audience Demographics Overview & Audience Interests; Mar. -

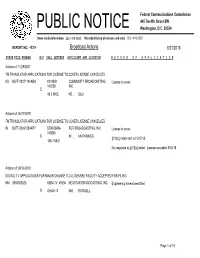

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-1-210201-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/01/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000133623 Renewal of FX K298AG 155267 107.5 NORFOLK, NE FLOOD 01/28/2021 Accepted License COMMUNICATIONS, For Filing L.L.C. From: To: 0000133486 License To FX W223DC 201383 92.5 BERLIN, NH WHITE MOUNTAINS 01/28/2021 Accepted Cover BROADCASTING, LLC For Filing From: To: 0000133665 Renewal of FL KYTF-LP 196817 94.7 BLAIR, NE BLAIR HEALING 01/28/2021 Accepted License ROOMS INC For Filing From: To: 0000133558 Minor FM KRSH 16257 Main 95.9 HEALDSBURG, SINCLAIR 01/28/2021 Accepted Modification CA TELECABLE, INC. D/B For Filing /A SINCLAIR COMMUNICATIONS From: To: 0000133401 Renewal of FM KKNL 122329 Main 89.3 VALENTINE, NE COMMUNITY PUBLIC 01/28/2021 Accepted License MEDIA For Filing From: To: 0000133247 Renewal of FM KXBL 68331 Main 99.5 HENRYETTA, GRIFFIN LICENSING, 01/27/2021 Accepted License OK L.L.C. For Filing From: To: Page 1 of 17 REPORT NO. PN-1-210201-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/01/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 APPLICATIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000132803 Renewal of DTV KEMV 2777 Main 210.0 MOUNTAIN Arkansas Educational 01/27/2021 Accepted License VIEW, AR Television Commission For Filing From: To: 0000133528 Renewal of AM KSCB 59803 Main 1270.0 LIBERAL, KS Seward County 01/28/2021 Accepted License Broadcasting Co., Inc. -

Broadcast Actions 8/21/2018

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 49304 Broadcast Actions 8/21/2018 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 11/29/2007 FM TRANSLATOR APPLICATIONS FOR LICENSE TO COVER LICENSE CANCELLED KS BLFT-20071101ABO K242BM COMMUNITY BROADCASTING, License to cover. 142058 INC. E 96.3 MHZ KS ,IOLA Actions of: 05/17/2018 FM TRANSLATOR APPLICATIONS FOR LICENSE TO COVER LICENSE CANCELLED IN BLFT-20061030APY DDW294BA FCR BROADCASTING, INC. License to cover. 143860 E IN ,VALPARAISO §312(g) letter sent on 5/17/18. 106.7 MHZ No response to §312(g) letter. License cancelled 8/16/18. Actions of: 08/16/2018 DIGITAL TV APPLICATIONS FOR MINOR CHANGE TO A LICENSED FACILITY ACCEPTED FOR FILING NM 0000002625 KBIM-TV 48556 NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. Engineering Amendment filed E CHAN-10 NM ,ROSWELL Page 1 of 16 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 49304 Broadcast Actions 8/21/2018 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 08/16/2018 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED UT BAL-20180625ABN KRRF 58303 RADIO LICENSE HOLDING CBC, Voluntary Assignment of License LLC From: RADIO LICENSE HOLDING CBC, LLC E 1230 KHZ To: KONA COAST RADIO, LLC UT , MURRAY Form 314 IA BAL-20180702AAZ KWPC 47085 WPW BROADCASTING, INC. -

Media Guide for Federal Leaders in Oklahoma

Media Guide for Federal Agencies Discussing the traditional forms of Media Interaction AND addressing the topic of Social Media! Oklahoma Federal Executive Board 215 Dean A. McGee, Suite 320 Oklahoma City, OK 73102 (405) 231-4167 www.oklahoma.feb.gov Distributed July 2011 INTRODUCTION Federal agencies have a responsibility to provide accurate and timely information to the general public and the media. In many cases, however, agencies do not have a person designated and trained as a Public Affairs Officer (PAO). In such instances, the CEO or a front-line employee must act as the agency's representative to the public. Many times, the intended message may be lost during the interview; often lack of planning or an inability to relay the message in succinct, easy to understand terms is the cause. Dealing with the media can be a daunting, nerve-wracking experience, whether it is in a face-to-face interview, phone interview or on camera. It is important to be at your best when communicating your message. This guide has been developed to assist those individuals called upon to speak on behalf of their agency to the press, both managerial and non-managerial employees. Whether you are responding to inquiries, arranging or participating in an interview, or simply providing information for print or broadcast, it is hoped that this media guide will provide you with useful information and some important tips to assist you. The purpose of this Media Guide is informational in nature for public employees. As in the past, the guidance is based on the principle that the business of Government is vital to serving the public everywhere. -

Station List

IN THIS ISSUE -NEW! FM Station I o List C ILA HUGO GERHSBACK, Editor BRUNETTI WRIST-WATCH TRANSMITTER SEE PAGE 28 SALES of previous editions offer the best evidence of its worth. Edition Year Copies sold 1st 1937 51,000 2nd 1938 25,000 3rd 1939 55,000 4th 1941 60,000 5th 1946 75,000 Here's what you get: Data on correct replace- ment parts Circuit information Servicing hints Installation notes IF peaks Tube complements and number of tubes References to Rider, giving Ready April 1st volume and page number RESERVE YOUR The 6th Edition COPY NOW Mallory Radio Service Encyclopedia Here it is -up to date -the only accurate, authorita- number of tubes ... and in addition, cross -index to tive radio service engineers guide, complete in one Rider by volume and page number for easy reference. GIVES YOU ALL THIS IN- volume -the Mallory Radio Service Encyclopedia, NO OTHER BOOK FORMATION- that's why it's a MUST for every 6th Edition. radio service engineer. Made up in the same easy -to -use form that proved 25% more listings than the 5th Edition. Our ability so popular in the 5th Edition, it gives you the to supply these books is taxed to the limit. The only complete facts on servicing all pre -war and post -war way of being sure that you will get your copy quickly sets ... volume and tone controls, capacitors, and is to order a copy today. Your Mallory Distributor vibrators ... circuit information, servicing hints, will reserve one for you. The cost to you is $2.00 net. -

Agencies, Boards, & Commissions

Agencies, Boards, & Commissions 228 229 Profiles of Agencies, Boards, and Commissions For information about boards or board members, contact the administrator. In the case of subordinate entities, unless a separate address and phone number are given, contact the main agency for information. For governor’s task forces, for example, contact the governor’s office; for legislative committees, contact the Legislative Service Bureau (405/521–4144). If the entity is not listed, consult the index, as it may be listed alphabetically beneath a par- ent entity. Personnel figures are provided by the agency. Interagency Mail availability is indicated by (IA). 2–1–1 Oklahoma Coordinating Council (56 O.S. § 3021) Formerly named the 2–1–1 Advisory Collaborative, Oklahoma www.211oklahoma.org Abstractors Board, Oklahoma (1 O.S. § 22) Re-created until July 1, 2019 Agency Code 022 (IA) www.abstract.ok.gov 2401 NW 23 Street, Suite 60B, Oklahoma City 73107 405/522–5019, fax 405/522–5503 Mission Statement The Oklahoma Abstractors Board regulates the abstracting industry and issues abstractor licenses, certificates of authority, and permits to construct abstract plants. Administration Glynda Reppond, Executive Director Personnel 2 unclassified History and Function The board consists of nine members, six of whom are in the abstracting industry, one real estate representative, one banking representative, and one attorney. All members are appointed by the governor and serve staggered four year terms. The board is responsible for promulgating rules, setting forth guidelines for agency operations, and governing the professional practices of the licensees. The entity is self-supporting through fees. Accountancy Board, Oklahoma (59 O.S. -

2020 Outstanding Achievement Awards Non-Metro Radio Division

2020 OUTSTANDING ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS NON-METRO RADIO DIVISION Newscast KECO 5pm Newscast Sportscast KECO The Skinny on Sports Report Play by Play KWON/KPGM OKWU Beats Ottawa 1st: KKZU Branbar Liquor: Effen Vodka Commercial Announcement 2nd: KOFM Top Choice Mechanical: On the Case 3rd: KOFM A1 Plumbing: Stuck KWON/KYFM Bartlesvilleradio.com Website KRIG/KPGM Station Image Promotion KWEY KWEY 50th Birthday Celebration Feature Story KICM KICM Kid’s Korner: Big Brother’s Ice Cream Station Event Promotion KICM KICM Homeland Big Grocery Grab E.W Marland Strikes Oil: A Day That Long Form Programming KPNC/KLOR Changed Ponca City Forever Video Streaming Sports KICM Ringling vs Thomas Football Video Streaming General KICM Lone Grove FBC Service Civil Discourse and Social KWON/KYFM Protest Downtown Bartlesville Change KRIG/KPGM Pandemic Response KOSB Triple Play’s COVID-19 Response Personality of the Year KOFM Alan Clepper BEST OF SHOW KICM, Ardmore Determined by number of awards and individual scores for each award. Awards will be presented at the OAB 2021 Virtual Convention. Date and Time to be announced. 6520 N. Western Avenue, Suite 104 Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73116 (405) 848-0771 Fax (405) 848-0772 Website: www.oabok.org E-mail: [email protected] 2020 OUTSTANDING ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS METRO RADIO DIVISION Newscast KRMG Morning News General News KRMG Officer Zarkeshan Comes Home Cancer Survivor Inspires Hikes in Feature Story KGOU Oklahoma to Experience Healing, Nature, and Community Website KRMG KRMG.com Station Image Promotion KVOO KVOO 98.5 The Bull Launch Station Event Promotion KWEN K95.5 Collects 955 Bikes for Kids Video Streaming General KRMG TPD Fundraiser Civil Discourse and Social Did George Floyd’s Death Affect KGOU Change Oklahoma’s Elections? Oklahoma Performance Venues Hit Hard Pandemic Response KGOU by COVID-19 Pandemic Election Coverage KRMG Election Night 2020 Personality of the Year KRMG Dan Potter BEST OF SHOW KRMG, Tulsa Determined by number of awards and individual scores for each award. -

Ms. Jan Sanders Secretary of the Commission Arkansas Public

, r-1 . 1- ,__ ARKANSAS 1 Sam 1. Bratton, Jr. PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION Chairman 1000 Center 682-1 453 P.O. Box 400 Patricia S. Qualls Little Rock, Arkansas 72203-0400 Commissioner 682- 145 1 Jerrell L. Clark Director Julius D. Kearney 682-1 794 Commissioner 682-1 455 .-I, i -1 -. < _,, , . Ms. Jan Sanders I* . ,, Secretary of the Commission Arkansas Public Service Commission 1000 Center Street P.O. Box 400 Little Rock, AR 72203-0400 RE: Docket: 92-178-U Dear Ms. Sanders: Attached for filing in the above referenced docket are copies of the: Public Service Announcement sent to radio and television stations, Mailing list of all radio and television stations to which the Public Service Announcement was mailed, Letter to State Legislators, Mailing list of all State Senators and State Representatives to which the letter was mailed, who have constituents living in Arkla Energy Resources' and Arkansas Louisiana Gas Company's service area, Letter to selected newspapers, Mailing list of selected newspapers to which the letter was mailed. These newspapers serve customers living in Arkla Energy Resources' and Arkansas Louisiana Gas Company's service area. Sincerely, 4' _A 'Jerrell Clark JC/pes attachment .:- ARKANSAS Sam 1. Bratton, Jr. PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION Chairman 1000 Center 682-1453 Box 400 P.O. Patricia S. Qualls Little Rock, Arkansas 72203-0400 Commissioner 682- 145 1 Jerrell L. Clark Director Julius D. Kearney 682-1 794 Commissioner 682-1455 August 24 , 1992 Senator Mike Bearden Post Office Box 1824 Blytheville, AR 72316 RE: Arkla Energy Kesources' and Arkansas Louisiana Gas Company's Public Hearing Dear Senator Bearden: Attached please find a copy of the legal notice regarding the public hearing for Arkla Energy Resources and Arkansas Louisiana Gas Company as it appeared in the Arkansas Democrat*Gazette on August 1, 1992. -

Judsonia Kensett Lake City Lake Village Lakeview Little Rock

KAOG Contemporary Christian* KPZK Urban Contemporary [Repeats: KIPR 92.3] 90.5 40000w 397ft DA Lake City 1250 2000/ 1200 DA-2 +American Family Association +Cltadel Communications Corp. KDXY Country™ 662-844-8888 fax: 662-842-6791 Sister to: KAAY, KARN, KARN-F, KIPR, KLAL, KURB 104.9 13500w 449ft PO Box 3206, Tupelo MS 38803 501-401-0200 fax: 501-401-0367 +Saga Communications, Inc. 107 Park Gate Dr, Tupelo MS 38801 700 Wellington Hills Rd, 72211 Sister to: KEGI, KJBX GM Marvin Sanders PD Rick Robertson GM/SM Richard Nickols PD Joe Booker 870-933-8800 fax: 870-933-0403 CE Joey Moody CE Dan Case 314 Union St, Jonesboro 72401 www.afr.net www.power923.com GM Trey Stafford SM Kevin Neathery Jonesboro Market Little Rock Market PD Christie Matthews CE Al Simpson KASU News /Classical /Jazz* www.thefox1049.com KTUV Spanish Jonesboro Arbitron 14.6 Shr 1300 AQH 91.9 100000W 688ft DA 1440 5000/240 DA-N Arkansas State University +Birach Broadcasting Corp. 870-972-3070 fax: 870-972-2997 Lake Village 877-426-1447 PO Box 2160, State University 72467 723 W Daisy L Gatson Bates Dr, 72202 104 Cooley St, Jonesboro 72467 KUUZ Religious Teaching* www.potencialatina.net GM Mike Doyle SM Todd Rutledge 95.9 20000w 302ft Little Rock Market PD Marty Scarbrough CE Eddy Arnold +Family Worship Center Church, Inc. www.kasu.org 225-768-3688 fax: 225-768-3729 KABF Variety* Jonesboro Market PO Box 262550, Baton Rouge LA 70826 88.3 100000W 776ft 8919 World Ministry Ave, Baton Rouge LA 70810 Arkansas Broadcasting Foundation KEGI Classic Hits GM/PD Ted Semper CE Tony Evans 501-372-6119 fax: 501-375-5965 100.5 38000w 558ft www.sonliferadio.org 2101 Main St Ste 200,72206 +Saga Communications, Inc.