Converting Enzyme (TACE&Sol;ADAM17)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neprilysin Is Required for Angiotensin-(1-7)

Page 1 of 39 Diabetes NEPRILYSIN IS REQUIRED FOR ANGIOTENSIN-(1-7)’S ABILITY TO ENHANCE INSULIN SECRETION VIA ITS PROTEOLYTIC ACTIVITY TO GENERATE ANGIOTENSIN-(1-2) Gurkirat S. Brara, Breanne M. Barrowa, Matthew Watsonb, Ryan Griesbachc, Edwina Chounga, Andrew Welchc, Bela Ruzsicskad, Daniel P. Raleighb, Sakeneh Zraikaa,c aVeterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, WA 98108, United States bDepartment of Chemistry, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794, United States cDivision of Metabolism, Endocrinology and Nutrition, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, United States dInstitute for Chemical Biology and Drug Discovery, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794, United States Short Title: Angiotensin-(1-7) and insulin secretion Word count: 3997; Figure count: 8 main (plus 3 Online Suppl.); Table count: 1 Online Suppl. Correspondence to: Sakeneh Zraika, PhD 1660 South Columbian Way (151) Seattle, WA, United States Tel: 206-768-5391 / Fax: 206-764-2164 Email: [email protected] 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online May 30, 2017 Diabetes Page 2 of 39 ABSTRACT Recent work has renewed interest in therapies targeting the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) to improve β-cell function in type 2 diabetes. Studies show that generation of angiotensin-(1-7) by angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and its binding to the Mas receptor (MasR) improves glucose homeostasis, partly by enhancing glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS). Thus, islet ACE2 upregulation is viewed as a desirable therapeutic goal. Here, we show that although endogenous islet ACE2 expression is sparse, its inhibition abrogates angiotensin-(1-7)-mediated GSIS. However, a more widely expressed islet peptidase, neprilysin, degrades angiotensin-(1-7) into several peptides. -

Proteasome 26S Subunit, Non Atpase 7 (PSMD7)

RPG282Hu01 10µg Recombinant Proteasome 26S Subunit, Non ATPase 7 (PSMD7) Organism Species: Homo sapiens (Human) Instruction manual FOR IN VITRO USE AND RESEARCH USE ONLY NOT FOR USE IN CLINICAL DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES 10th Edition (Revised in Jan, 2014) [ PROPERTIES ] Residues: Met1~Lys324 Tags: Two N-terminal Tags, His-tag and T7-tag Accession: P51665 Host: E. coli Purity: >90% Endotoxin Level: <1.0EU per 1μg (determined by the LAL method). Formulation: Supplied as lyophilized form in 20mM Tris, 150mM NaCl, pH8.0, containing 1mM EDTA, 1mM DTT, 0.01% sarcosyl, 5% trehalose, and preservative. Predicted isoelectric point: 6.7 Predicted Molecular Mass: 40.8kDa Applications: SDS-PAGE; WB; ELISA; IP. (May be suitable for use in other assays to be determined by the end user.) [ USAGE ] Reconstitute in sterile ddH2O. [ STORAGE AND STABILITY ] Storage: Avoid repeated freeze/thaw cycles. Store at 2-8oC for one month. Aliquot and store at -80oC for 12 months. Stability Test: The thermal stability is described by the loss rate of the target protein. The loss rate was determined by accelerated thermal degradation test, that is, incubate the protein at 37oC for 48h, and no obvious degradation and precipitation were observed. (Referring from China Biological Products Standard, which was calculated by the Arrhenius equation.) The loss of this protein is less than 5% within the expiration date under appropriate storage condition. [ SEQUENCES ] The sequence of the target protein is listed below. MPELAVQKVV VHPLVLLSVV DHFNRIGKVG NQKRVVGVLL GSWQKKVLDV SNSFAVPFDE DDKDDSVWFL DHDYLENMYG MFKKVNARER IVGWYHTGPK LHKNDIAINE LMKRYCPNSV LVIIDVKPKD LGLPTEAYIS VEEVHDDGTP TSKTFEHVTS EIGAEEAEEV GVEHLLRDIK DTTVGTLSQR ITNQVHGLKG LNSKLLDIRS YLEKVATGKL PINHQIIYQL QDVFNLLPDV SLQEFVKAFY LKTNDQMVVV YLASLIRSVV ALHNLINNKI ANRDAEKKEG QEKEESKKDR KEDKEKDKDK EKSDVKKEEK KEKK [ REFERENCES ] 1. -

Proteasome System of Protein Degradation and Processing

ISSN 0006-2979, Biochemistry (Moscow), 2009, Vol. 74, No. 13, pp. 1411-1442. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2009. Original Russian Text © A. V. Sorokin, E. R. Kim, L. P. Ovchinnikov, 2009, published in Uspekhi Biologicheskoi Khimii, 2009, Vol. 49, pp. 3-76. REVIEW Proteasome System of Protein Degradation and Processing A. V. Sorokin*, E. R. Kim, and L. P. Ovchinnikov Institute of Protein Research, Russian Academy of Sciences, 142290 Pushchino, Moscow Region, Russia; E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received February 5, 2009 Abstract—In eukaryotic cells, degradation of most intracellular proteins is realized by proteasomes. The substrates for pro- teolysis are selected by the fact that the gate to the proteolytic chamber of the proteasome is usually closed, and only pro- teins carrying a special “label” can get into it. A polyubiquitin chain plays the role of the “label”: degradation affects pro- teins conjugated with a ubiquitin (Ub) chain that consists at minimum of four molecules. Upon entering the proteasome channel, the polypeptide chain of the protein unfolds and stretches along it, being hydrolyzed to short peptides. Ubiquitin per se does not get into the proteasome, but, after destruction of the “labeled” molecule, it is released and labels another molecule. This process has been named “Ub-dependent protein degradation”. In this review we systematize current data on the Ub–proteasome system, describe in detail proteasome structure, the ubiquitination system, and the classical ATP/Ub- dependent mechanism of protein degradation, as well as try to focus readers’ attention on the existence of alternative mech- anisms of proteasomal degradation and processing of proteins. -

Cell-Autonomous FLT3L Shedding Via ADAM10 Mediates Conventional Dendritic Cell Development in Mouse Spleen

Cell-autonomous FLT3L shedding via ADAM10 mediates conventional dendritic cell development in mouse spleen Kohei Fujitaa,b,1, Svetoslav Chakarovc,1, Tetsuro Kobayashid, Keiko Sakamotod, Benjamin Voisind, Kaibo Duanc, Taneaki Nakagawaa, Keisuke Horiuchie, Masayuki Amagaib, Florent Ginhouxc, and Keisuke Nagaod,2 aDepartment of Dentistry and Oral Surgery, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo 160-8582, Japan; bDepartment of Dermatology, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo 160-8582, Japan; cSingapore Immunology Network, Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Biopolis, 138648 Singapore; dDermatology Branch, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; and eDepartment of Orthopedic Surgery, National Defense Medical College, Tokorozawa 359-8513, Japan Edited by Kenneth M. Murphy, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, and approved June 10, 2019 (received for review November 4, 2018) Conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) derive from bone marrow (BM) intocDC1sorcDC2stakesplaceintheBM(3),andthese precursors that undergo cascades of developmental programs to pre-cDC1s and pre-cDC2s ultimately differentiate into cDC1s terminally differentiate in peripheral tissues. Pre-cDC1s and pre- and cDC2s after migrating to nonlymphoid and lymphoid tissues. + + cDC2s commit in the BM to each differentiate into CD8α /CD103 cDCs are short-lived, and their homeostatic maintenance relies + cDC1s and CD11b cDC2s, respectively. Although both cDCs rely on on constant replenishment from the BM precursors (5). The cy- the cytokine FLT3L during development, mechanisms that ensure tokine Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (FLT3L) (12), by cDC accessibility to FLT3L have yet to be elucidated. Here, we gen- signaling through its receptor FLT3 expressed on DC precursors, erated mice that lacked a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) is essential during the development of DCs (7, 13). -

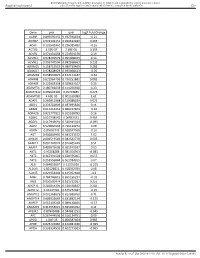

Gene Pval Qval Log2 Fold Change AAMP 0.895690332 0.952598834

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) Gut Gene pval qval Log2 Fold Change AAMP 0.895690332 0.952598834 -0.21 ABI3BP 0.002302151 0.020612283 0.465 ACHE 0.103542461 0.296385483 -0.16 ACTG2 2.99E-07 7.68E-05 3.195 ACVR1 0.071431098 0.224504378 0.19 ACVR1C 0.978209579 0.995008423 0.14 ACVRL1 0.006747504 0.042938663 0.235 ADAM15 0.158715519 0.380719469 0.285 ADAM17 0.978208929 0.995008423 -0.05 ADAM28 0.038932876 0.152174187 -0.62 ADAM8 0.622964796 0.790251882 0.085 ADAM9 0.122003358 0.329623107 0.25 ADAMTS1 0.180766659 0.414256926 0.23 ADAMTS12 0.009902195 0.05703885 0.425 ADAMTS8 4.60E-05 0.001169089 1.61 ADAP1 0.269811968 0.519388039 0.075 ADD1 0.233702809 0.487695826 0.11 ADM2 0.012213453 0.066227879 -0.36 ADRA2B 0.822777921 0.915518785 0.16 AEBP1 0.010738542 0.06035531 0.465 AGGF1 0.117946691 0.320915024 -0.095 AGR2 0.529860903 0.736120272 0.08 AGRN 0.85693743 0.928047568 -0.16 AGT 0.006849995 0.043233572 1.02 AHNAK 0.006519543 0.042542779 0.605 AKAP12 0.001747074 0.016405449 0.51 AKAP2 0.409929603 0.665919397 0.05 AKT1 0.95208288 0.985354963 -0.085 AKT2 0.367391504 0.620376005 0.055 AKT3 0.253556844 0.501934205 0.07 ALB 0.064833867 0.21195036 -0.315 ALDOA 0.83128831 0.918352939 0.08 ALOX5 0.029954404 0.125352668 -0.3 AMH 0.784746815 0.895196237 -0.03 ANG 0.050500474 0.181732067 0.255 ANGPT1 0.281853305 0.538528647 0.285 ANGPT2 0.43147281 0.675272487 -0.15 ANGPTL2 0.001368876 0.013688762 0.71 ANGPTL4 0.686032669 0.831882134 -0.175 ANPEP 0.019103243 0.089148466 -0.57 ANXA2P2 0.412553021 0.665966092 0.11 AP1M2 0.87843088 0.944681253 -0.045 APC 0.267444505 0.516134751 0.09 APOD 1.04E-05 0.000587404 0.985 APOE 0.023722987 0.104981036 -0.395 APOH 0.336334555 0.602273505 -0.065 Sundar R, et al. -

A Novel Proteasome Inhibitor NPI-0052 As an Anticancer Therapy

British Journal of Cancer (2006) 95, 961 – 965 & 2006 Cancer Research UK All rights reserved 0007 – 0920/06 $30.00 www.bjcancer.com Minireview A novel proteasome inhibitor NPI-0052 as an anticancer therapy 1 1 ,1 D Chauhan , T Hideshima and KC Anderson* 1Department of Medical Oncology, Harvard Medical School, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, The Jerome Lipper Multiple Myeloma Center, Boston, MA 02115, USA Proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib/Velcade has emerged as an effective anticancer therapy for the treatment of relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma (MM), but prolonged treatment can be associated with toxicity and development of drug resistance. In this review, we discuss the recent discovery of a novel proteasome inhibitor, NPI-0052, that is distinct from Bortezomib in its chemical structure, mechanisms of action, and effects on proteasomal activities; most importantly, it overcomes resistance to conventional and Bortezomib therapies. In vivo studies using human MM xenografts shows that NPI-0052 is well tolerated, prolongs survival, and reduces tumour recurrence. These preclinical studies provided the basis for Phase-I clinical trial of NPI-0052 in relapsed/ refractory MM patients. British Journal of Cancer (2006) 95, 961–965. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603406 www.bjcancer.com & 2006 Cancer Research UK Keywords: protein degradation; proteasomes; multiple myeloma; novel therapy; apoptosis; drug resistance The systemic regulation of protein synthesis and protein degrada- inducible immunoproteasomes b-5i, b-1i, b-2i with different tion is essential -

Gene Standard Deviation MTOR 0.12553731 PRPF38A

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) Gut Gene Standard Deviation MTOR 0.12553731 PRPF38A 0.141472605 EIF2B4 0.154700091 DDX50 0.156333027 SMC3 0.161420017 NFAT5 0.166316903 MAP2K1 0.166585267 KDM1A 0.16904912 RPS6KB1 0.170330192 FCF1 0.170391706 MAP3K7 0.170660513 EIF4E2 0.171572093 TCEB1 0.175363093 CNOT10 0.178975095 SMAD1 0.179164705 NAA15 0.179904998 SETD2 0.180182498 HDAC3 0.183971158 AMMECR1L 0.184195031 CHD4 0.186678211 SF3A3 0.186697697 CNOT4 0.189434633 MTMR14 0.189734199 SMAD4 0.192451524 TLK2 0.192702667 DLG1 0.19336621 COG7 0.193422331 SP1 0.194364189 PPP3R1 0.196430217 ERBB2IP 0.201473001 RAF1 0.206887192 CUL1 0.207514271 VEZF1 0.207579584 SMAD3 0.208159809 TFDP1 0.208834504 VAV2 0.210269344 ADAM17 0.210687138 SMURF2 0.211437666 MRPS5 0.212428684 TMUB2 0.212560675 SRPK2 0.216217428 MAP2K4 0.216345366 VHL 0.219735582 SMURF1 0.221242495 PLCG1 0.221688351 EP300 0.221792349 Sundar R, et al. Gut 2020;0:1–10. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320805 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) Gut MGAT5 0.222050228 CDC42 0.2230598 DICER1 0.225358787 RBX1 0.228272533 ZFYVE16 0.22831803 PTEN 0.228595789 PDCD10 0.228799406 NF2 0.23091035 TP53 0.232683696 RB1 0.232729172 TCF20 0.2346075 PPP2CB 0.235117302 AGK 0.235416298 -

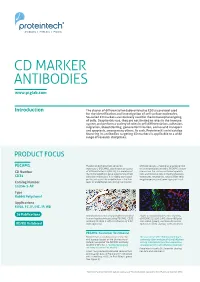

CD Markers Are Routinely Used for the Immunophenotyping of Cells

ptglab.com 1 CD MARKER ANTIBODIES www.ptglab.com Introduction The cluster of differentiation (abbreviated as CD) is a protocol used for the identification and investigation of cell surface molecules. So-called CD markers are routinely used for the immunophenotyping of cells. Despite this use, they are not limited to roles in the immune system and perform a variety of roles in cell differentiation, adhesion, migration, blood clotting, gamete fertilization, amino acid transport and apoptosis, among many others. As such, Proteintech’s mini catalog featuring its antibodies targeting CD markers is applicable to a wide range of research disciplines. PRODUCT FOCUS PECAM1 Platelet endothelial cell adhesion of blood vessels – making up a large portion molecule-1 (PECAM1), also known as cluster of its intracellular junctions. PECAM-1 is also CD Number of differentiation 31 (CD31), is a member of present on the surface of hematopoietic the immunoglobulin gene superfamily of cell cells and immune cells including platelets, CD31 adhesion molecules. It is highly expressed monocytes, neutrophils, natural killer cells, on the surface of the endothelium – the thin megakaryocytes and some types of T-cell. Catalog Number layer of endothelial cells lining the interior 11256-1-AP Type Rabbit Polyclonal Applications ELISA, FC, IF, IHC, IP, WB 16 Publications Immunohistochemical of paraffin-embedded Figure 1: Immunofluorescence staining human hepatocirrhosis using PECAM1, CD31 of PECAM1 (11256-1-AP), Alexa 488 goat antibody (11265-1-AP) at a dilution of 1:50 anti-rabbit (green), and smooth muscle KD/KO Validated (40x objective). alpha-actin (red), courtesy of Nicola Smart. PECAM1: Customer Testimonial Nicola Smart, a cardiovascular researcher “As you can see [the immunostaining] is and a group leader at the University of extremely clean and specific [and] displays Oxford, has said of the PECAM1 antibody strong intercellular junction expression, (11265-1-AP) that it “worked beautifully as expected for a cell adhesion molecule.” on every occasion I’ve tried it.” Proteintech thanks Dr. -

The Disintegrin/Metalloproteinase ADAM10 Is Essential for the Establishment of the Brain Cortex

The Journal of Neuroscience, April 7, 2010 • 30(14):4833–4844 • 4833 Development/Plasticity/Repair The Disintegrin/Metalloproteinase ADAM10 Is Essential for the Establishment of the Brain Cortex Ellen Jorissen,1,2* Johannes Prox,3* Christian Bernreuther,4 Silvio Weber,3 Ralf Schwanbeck,3 Lutgarde Serneels,1,2 An Snellinx,1,2 Katleen Craessaerts,1,2 Amantha Thathiah,1,2 Ina Tesseur,1,2 Udo Bartsch,5 Gisela Weskamp,6 Carl P. Blobel,6 Markus Glatzel,4 Bart De Strooper,1,2 and Paul Saftig3 1Center for Human Genetics, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven and 2Department for Developmental and Molecular Genetics, Vlaams Instituut voor Biotechnologie (VIB), 3000 Leuven, Belgium, 3Institut fu¨r Biochemie, Christian-Albrechts-Universita¨t zu Kiel, D-24098 Kiel, Germany, 4Institute of Neuropathology, University Medical Center Hamburg Eppendorf, 20246 Hamburg, Germany, 5Department of Ophthalmology, University Medical Center Hamburg Eppendorf, 20246 Hamburg, Germany, and 6Arthritis and Tissue Degeneration Program, Hospital for Special Surgery, and Departments of Medicine and of Physiology, Systems Biology and Biophysics, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, New York 10021 The metalloproteinase and major amyloid precursor protein (APP) ␣-secretase candidate ADAM10 is responsible for the shedding of ,proteins important for brain development, such as cadherins, ephrins, and Notch receptors. Adam10 ؊/؊ mice die at embryonic day 9.5 due to major defects in development of somites and vasculogenesis. To investigate the function of ADAM10 in brain, we generated Adam10conditionalknock-out(cKO)miceusingaNestin-Crepromotor,limitingADAM10inactivationtoneuralprogenitorcells(NPCs) and NPC-derived neurons and glial cells. The cKO mice die perinatally with a disrupted neocortex and a severely reduced ganglionic eminence, due to precocious neuronal differentiation resulting in an early depletion of progenitor cells. -

PSMB8 Gene Proteasome Subunit Beta 8

PSMB8 gene proteasome subunit beta 8 Normal Function The PSMB8 gene provides instructions for making one part (subunit) of cell structures called immunoproteasomes. Immunoproteasomes are specialized versions of proteasomes, which are large complexes that recognize and break down (degrade) unneeded, excess, or abnormal proteins within cells. This activity is necessary for many essential cell functions. While proteasomes are found in many types of cells, immunoproteasomes are located primarily in immune system cells. These structures play an important role in regulating the immune system's response to foreign invaders, such as viruses and bacteria. One of the primary functions of immunoproteasomes is to help the immune system distinguish the body's own proteins from proteins made by foreign invaders, so the immune system can respond appropriately to infection. Immunoproteasomes may also have other functions in immune system cells and possibly in other types of cells. They appear to be involved in some of the same fundamental cell activities as regular proteasomes, such as regulating the amount of various proteins in cells (protein homeostasis), cell growth and division, the process by which cells mature to carry out specific functions (differentiation), chemical signaling within cells, and the activity of genes. Studies suggest that, through unknown mechanisms, the subunit produced from the PSMB8 gene in particular may be involved in the maturation of fat cells (adipocytes). Health Conditions Related to Genetic Changes Nakajo-Nishimura syndrome At least one mutation in the PSMB8 gene has been found to cause Nakajo-Nishimura syndrome, a condition that has been described only in the Japanese population. The identified mutation changes a single protein building block (amino acid) in the protein produced from the PSMB8 gene, replacing the amino acid glycine with the amino acid valine at protein position 201 (written as Gly201Val or G201V). -

Proteasome Biology: Chemistry and Bioengineering Insights

polymers Review Proteasome Biology: Chemistry and Bioengineering Insights Lucia Raˇcková * and Erika Csekes Centre of Experimental Medicine, Institute of Experimental Pharmacology and Toxicology, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Dúbravská cesta 9, 841 04 Bratislava, Slovakia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Received: 28 September 2020; Accepted: 23 November 2020; Published: 4 December 2020 Abstract: Proteasomal degradation provides the crucial machinery for maintaining cellular proteostasis. The biological origins of modulation or impairment of the function of proteasomal complexes may include changes in gene expression of their subunits, ubiquitin mutation, or indirect mechanisms arising from the overall impairment of proteostasis. However, changes in the physico-chemical characteristics of the cellular environment might also meaningfully contribute to altered performance. This review summarizes the effects of physicochemical factors in the cell, such as pH, temperature fluctuations, and reactions with the products of oxidative metabolism, on the function of the proteasome. Furthermore, evidence of the direct interaction of proteasomal complexes with protein aggregates is compared against the knowledge obtained from immobilization biotechnologies. In this regard, factors such as the structures of the natural polymeric scaffolds in the cells, their content of reactive groups or the sequestration of metal ions, and processes at the interface, are discussed here with regard to their -

Cleavage of the Extracellular Domain of Junctional Adhesion Molecule-A Is Associated with Resistance to Anti-HER2 Therapies in Breast Cancer Settings Astrid O

Leech et al. Breast Cancer Research (2018) 20:140 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-018-1064-1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Cleavage of the extracellular domain of junctional adhesion molecule-A is associated with resistance to anti-HER2 therapies in breast cancer settings Astrid O. Leech1, Sri HariKrishna Vellanki1†, Emily J. Rutherford1†, Aoife Keogh1, Hanne Jahns2, Lance Hudson1, Norma O’Donovan3, Siham Sabri4, Bassam Abdulkarim5, Katherine M. Sheehan6, Elaine W. Kay6, Leonie S. Young1, Arnold D. K. Hill1, Yvonne E. Smith1 and Ann M. Hopkins1* Abstract Background: Junctional adhesion molecule-A (JAM-A) is an adhesion molecule whose overexpression on breast tumor tissue has been associated with aggressive cancer phenotypes, including human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-positive disease. Since JAM-A has been described to regulate HER2 expression in breast cancer cells, we hypothesized that JAM-dependent stabilization of HER2 could participate in resistance to HER2-targeted therapies. Methods: Using breast cancer cell line models resistant to anti-HER2 drugs, we investigated JAM-A expression and the effect of JAM-A silencing on biochemical/functional parameters. We also tested whether altered JAM-A expression/ processing underpinned differences between drug-sensitive and -resistant cells and acted as a biomarker of patients who developed resistance to HER2-targeted therapies. Results: Silencing JAM-A enhanced the anti-proliferative effects of anti-HER2 treatments in trastuzumab- and lapatinib- resistant breast cancer cells and further reduced HER2 protein expression and Akt phosphorylation in drug-treated cells. Increased epidermal growth factor receptor expression observed in drug-resistant models was normalized upon JAM-A silencing.