Bergman Black Metal and Hour of the Wolf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Films of Ingmar Bergman: Centennial Celebration!

The Films of Ingmar Bergman: Centennial Celebration! Swedish filmmaker, author, and film director Ingmar Bergman was born in 1918, so this year will be celebrated in Sweden and around the world by those who have been captivated by his work. Bergman belongs to a group of filmmakers who were hailed as "auteurs" (authors) in the 1960s by French, then American film critics, and his work was part of a wave of "art cinema," a form that elevated "movies" to "films." In this course we will analyze in detail six films by Bergman and read short pieces by Bergman and scholars. We will discuss the concept of film authorship, Bergman's life and work, and his cinematic world. Note: some of the films to be screened contain emotionally or physically disturbing content. The films listed below should be viewed BEFORE the scheduled OLLI class. All films will be screened at the PFA Osher Theater on Wednesdays at 3-5pm, the day before the class lecture on that film. Screenings are open to the public for the usual PFA admission. All films are also available in DVD format (for purchase on Amazon and other outlets or often at libraries) or on- line through such services as FilmStruck (https://www.filmstruck.com/us/) or, in some cases, on YouTube (not as reliable). Films Week 1: 9/27 Wild Strawberries (1957, 91 mins) NOTE: screening at PFA Weds 9/25 Week 2: 10/4 The Virgin Spring (1960, 89 mins) Week 3: 10/11 Winter Light (1963, 80 mins) Week 4: 10/18 The Silence (1963, 95 mins) Week 5: 10/25 Persona (1966, 85 mins) Week 6: 11/1 Hour of the Wolf (1968, 90 mins) -

PDF (1.85 Mib)

セM ...............................____________________ ,._ ______ ______________ セ セ セM MARCH 2, 2012 ARCADE B4 Getting to know the Gentlemen of Verona BY DERRICK TOUPS DT: How was it working specifically on "Two SENIOR STAFF WRITER Gents;' a lesser-known Shakespeare play? It's one of his earliest, so it's not as strong as his lat- er works. With a colorful cast of vampires, skate- SE: It is a pretty clumsy play. There's a horrible boarders, potheads and preps, the department ending where Pr9teus has an attempted rape, of theatre and dance opened its "Clerks"-style then Valentine discovers him, rescues Sylvia, rendition of Shakespeare's "Two Gentlemen of and decides, "Oh, you can have her because Verona," directed by Gary Rucker, Tuesday in our friendship's more important." It's definite- conjunction with The Shakespeare Festival at ly a play of problems, but it's cool to see ear- Tulane. The Arcade sat down with the two gen- ly things that Shakespeare later develops like tlemen themselves, sophomore Jesse Friedman cross-dressing, the weird attraction to those in (Valentine) and senior Stephen Eckert (Prote- drag and the sympathetic servants. us), to discuss the process of putting on the de- JF: Something that I think is attractive about partment's first Shakespeare play since "Cym- a lot of Shakespearean comedies - this may beline" in 2004. sound weird - is the naivete of his protago- nists. I think it's pretty endearing and attracts Derrick Toups: You've both worked with the audience to the characters. Shakespeare before, through monologues and scenes. -

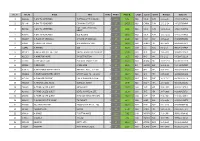

Bertus in Stock 7-4-2014

No. # Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price €. Origin Label Genre Release Eancode 1 G98139 A DAY TO REMEMBER 7-ATTACK OF THE KILLER.. 1 12in 6,72 NLD VIC.R PUN 21-6-2010 0746105057012 2 P10046 A DAY TO REMEMBER COMMON COURTESY 2 LP 24,23 NLD CAROL PUN 13-2-2014 0602537638949 FOR THOSE WHO HAVE 3 E87059 A DAY TO REMEMBER 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 14-11-2008 0746105033719 HEART 4 K78846 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 31-10-2011 0746105049413 5 M42387 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS 1 LP 20,23 NLD MOV POP 13-6-2013 8718469532964 6 L49081 A FOREST OF STARS A SHADOWPLAY FOR.. 2 LP 38,68 NLD PROPH HM. 20-7-2012 0884388405011 7 J16442 A FRAMES 333 3 LP 38,73 USA S-S ROC 3-8-2010 9991702074424 8 M41807 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVE YOU'RE ALWAYS ON MY MIND 1 LP 24,06 NLD PHD POP 10-6-2013 0616892111641 9 K81313 A HOPE FOR HOME IN ABSTRACTION 1 LP 18,53 NLD PHD HM. 5-1-2012 0803847111119 10 L77989 A LIFE ONCE LOST ECSTATIC TRANCE -LTD- 1 LP 32,47 NLD SEASO HC. 15-11-2012 0822603124316 11 P33696 A NEW LINE A NEW LINE 2 LP 29,92 EU HOMEA ELE 28-2-2014 5060195515593 12 K09100 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH AND HELL WILL.. -LP+CD- 3 LP 30,43 NLD SPV HM. 16-6-2011 0693723093819 13 M32962 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH LAY MY SOUL TO. -

![HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8672/how-black-is-black-metal-journalismus-nachrichten-von-heute-488672.webp)

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] nachrichten von heute Kevin Coogan - Lords of Chaos (LOC), a recent book-length examination of the “Satanic” black metal music scene, is less concerned with sound than fury. Authors Michael Moynihan and Didrik Sederlind zero in on Norway, where a tiny clique of black metal musicians torched some churches in 1992. The church burners’ own place of worship was a small Oslo record store called Helvete (Hell). Helvete was run by the godfather of Norwegian black metal, 0ystein Aarseth (“Euronymous”, or “Prince of Death”), who first brought black metal to Norway with his group Mayhem and his Deathlike Silence record label. One early member of the movement, “Frost” from the band Satyricon, recalled his first visit to Helvete: I felt like this was the place I had always dreamed about being in. It was a kick in the back. The black painted walls, the bizarre fitted out with inverted crosses, weapons, candelabra etc. And then just the downright evil atmosphere...it was just perfect. Frost was also impressed at how talented Euronymous was in “bringing forth the evil in people – and bringing the right people together” and then dominating them. “With a scene ruled by the firm hand of Euronymous,” Frost reminisced, “one could not avoid a certain herd-mentality. There were strict codes for what was accept- ed.” Euronymous may have honed his dictatorial skills while a member of Red Ungdom (Red Youth), the youth wing of the Marxist/Leninist Communist Workers Party, a Stalinist/Maoist outfit that idolized Pol Pot. All who wanted to be part of black metal’s inner core “had to please the leader in one way or the other.” Yet to Frost, Euronymous’s control over the scene was precisely “what made it so special and obscure, creating a center of dark, evil energies and inspiration.” Lords of Chaos, however, is far less interested in Euronymous than in the man who killed him, Varg Vikemes from the one-man group Burzum. -

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal *

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal * Stephen S. Hudson NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.1/mto.21.27.1.hudson.php KEYWORDS: Heavy Metal, Formenlehre, Form Perception, Embodied Cognition, Corpus Study, Musical Meaning, Genre ABSTRACT: This article presents a new framework for analyzing compound AABA form in heavy metal music, inspired by normative theories of form in the Formenlehre tradition. A corpus study shows that a particular riff-based version of compound AABA, with a specific style of buildup intro (Aas 2015) and other characteristic features, is normative in mainstream styles of the metal genre. Within this norm, individual artists have their own strategies (Meyer 1989) for manifesting compound AABA form. These strategies afford stylistic distinctions between bands, so that differences in form can be said to signify aesthetic posing or social positioning—a different kind of signification than the programmatic or semantic communication that has been the focus of most existing music theory research in areas like topic theory or musical semiotics. This article concludes with an exploration of how these different formal strategies embody different qualities of physical movement or feelings of motion, arguing that in making stylistic distinctions and identifying with a particular subgenre or style, we imagine that these distinct ways of moving correlate with (sub)genre rhetoric and the physical stances of imagined communities of fans (Anderson 1983, Hill 2016). Received January 2020 Volume 27, Number 1, March 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory “Your favorite songs all sound the same — and that’s okay . -

DARKWOODS MAILORDER CATALOGUE March 2018

DARKWOODS MAILORDER CATALOGUE March 2018 DARKWOODS PAGAN BLACK METAL DI STRO / LABEL [email protected] www.darkwoods.eu Next you will find a full list with all available items in our mailorder catalogue alphabetically ordered... With the exception of the respective cover, we have included all relevant information about each item, even the format, the releasing label and the reference comment... This catalogue is updated every month, so it could not reflect the latest received products or the most recent sold-out items... please use it more as a reference than an updated list of our products... CDS / MCDS / SGCDS 1349 - Beyond the Apocalypse [CD] 11.95 EUR Second smash hit of the Norwegians 1349, nine outstanding tracks of intense, very fast and absolutely brutal black metal is what they offer us with “Beyond the Apocalypse”, with Frost even more a beast behind the drum set here than in Satyricon, excellent! [Released by Candlelight] 1349 - Demonoir [CD] 11.95 EUR Fifth full-length album of this Norwegian legion, recovering in one hand the intensity and brutality of the fantastic “Hellfire” but, at the same time, continuing with the experimental and sinister side of their music introduced in their previous work, “Revelations of the Black Flame”... [Released by Indie Recordings] 1349 - Liberation [CD] 11.95 EUR Fantastic debut full-length album of the Nordic hordes 1349 leaded by Frost (Satyricon), ten tracks of furious, violent and merciless black metal is what they show us in "Liberation", ten straightforward tracks of pure Norwegian black metal, superb! [Released by Candlelight] 1349 - Massive Cauldron of Chaos [CD] 11.95 EUR Sixth full-length album of the Norwegians 1349, with which they continue this returning path to their most brutal roots that they started with the previous “Demonoir”, perhaps not as chaotic as the title might suggested, but we could place it in the intermediate era of “Hellfire”.. -

Hipster Black Metal?

Hipster Black Metal? Deafheaven’s Sunbather and the Evolution of an (Un) popular Genre Paola Ferrero A couple of months ago a guy walks into a bar in Brooklyn and strikes up a conversation with the bartenders about heavy metal. The guy happens to mention that Deafheaven, an up-and-coming American black metal (BM) band, is going to perform at Saint Vitus, the local metal concert venue, in a couple of weeks. The bartenders immediately become confrontational, denying Deafheaven the BM ‘label of authenticity’: the band, according to them, plays ‘hipster metal’ and their singer, George Clarke, clearly sports a hipster hairstyle. Good thing they probably did not know who they were talking to: the ‘guy’ in our story is, in fact, Jonah Bayer, a contributor to Noisey, the music magazine of Vice, considered to be one of the bastions of hipster online culture. The product of that conversation, a piece entitled ‘Why are black metal fans such elitist assholes?’ was almost certainly intended as a humorous nod to the ongoing debate, generated mainly by music webzines and their readers, over Deafheaven’s inclusion in the BM canon. The article features a promo picture of the band, two young, clean- shaven guys, wearing indistinct clothing, with short haircuts and mild, neutral facial expressions, their faces made to look like they were ironically wearing black and white make up, the typical ‘corpse-paint’ of traditional, early BM. It certainly did not help that Bayer also included a picture of Inquisition, a historical BM band from Colombia formed in the early 1990s, and ridiculed their corpse-paint and black cloaks attire with the following caption: ‘Here’s what you’re defending, black metal purists. -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

d o n e i t . MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS R Tit e l der M a s t erarbei t / Titl e of the Ma s t er‘ s Thes i s e „What Never Was": a Lis t eni ng to th e Genesis of B lack Met al d M o v erf a ss t v on / s ubm itted by r Florian Walch, B A e : anges t rebt e r a k adem is c her Grad / i n par ti al f ul fi l men t o f t he requ i re men t s for the deg ree of I Ma s ter o f Art s ( MA ) n t e Wien , 2016 / V i enna 2016 r v i Studien k enn z ahl l t. Studienbla t t / A 066 836 e deg r ee p rogramm e c ode as i t appea r s o n t he st ude nt r eco rd s hee t: w Studien r i c h tu ng l t. Studienbla tt / Mas t er s t udi um Mu s i k w is s ens c ha ft U G 2002 : deg r ee p r o g r amme as i t appea r s o n t he s tud e nt r eco r d s h eet : B et r eut v on / S uper v i s or: U ni v .-Pr o f. Dr . Mi c hele C a l ella F e n t i z |l 2 3 4 Table of Contents 1. -

The Playfulness of Ingmar Bergman: Screenwriting from Notebooks to Screenplays

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES www.necsus-ejms.org The playfulness of Ingmar Bergman: Screenwriting from notebooks to screenplays Anna Sofia Rossholm NECSUS (7), 2: Autumn 2018: 23–42 URL: https://necsus-ejms.org/the-playfulness-of-ingmar-bergman- screenwriting-from-notebooks-to-screenplays/ Keywords: archive, creative writing, genetic criticism, Ingmar Berg- man, Persona, play, screenplays, screenwriting The voice: You said you wanted to ‘play and fantasise’. Bergman: We can always try. The voice: That’s what you said: play and fantasise. Bergman: Sounds good. You don’t exist, yet you do. The voice: If this venture is going to make sense, you have to describe me. In detail actually. Bergman: Sit down on the chair by the window and I’ll describe you. The voice: I won’t sit down unless you describe me. Bergman: Well then. And how do I begin? You are very attractive. Most attractive.[1] This is the beginning of Ingmar Bergman’s screenplay Trolösa (Faithless, di- rected by Liv Ullmann in 2000). The dialogue, which is a prologue to the story, is a playful depiction of the author’s creative development of a fictional character. Step by step ‘the voice’ in the scene is given a body, name, and characteristics. Gradually she becomes the character ‘Marianne’. The question is how truthful this scene is to the actual creative process? Of course, it is not a description of what really happened in Bergman’s mind. The character Marianne probably did not appear as a sudden fantasy in the mind of the author. She is more likely a result of a long mental process over NECSUS – EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES many years. -

Intermediality As a Tool for Aesthetic Analysis and Critical Reflection, Edited by Sonya Petersson, Christer Johansson, Magdalena Holdar, and Sara Callahan, 49–74

The Intersection between Film and Opera in the 1960s: Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf as an Example of Formal Imitation Johanna Ethnersson Pontara Abstract The topic of this article is the intersection between media genres in 1960s Sweden. In a case study of Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf (1968) it is shown how the music contributes to intermedial qualities through the film’s connection with opera. It is argued that the film, by how the music is related to sound effects and images, can be seen as an example of formal imitation. The imitation of opera is created through technical media of film, such as fore- grounding of media in the audio-visual space, and manipulations of sounds, music, and images. Of special interest is how, by alter- nating between synchronicity and counterpoint between images, sound effects, and music, Bergman attracts attention to the media as visual and sonic experiences and creates formal structures that deviate from the overall character of the film. The intermedial di- mension of the film revealed by the analysis is contextualized in re- lation to the historical discussion of mixed versus pure medialities. The film is seen in the light of an interest in media genre mixedness versus media genre specificity in 1960s Sweden. Introduction In a review of Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf (Vargtimmen, 1968) published in the American film journalFilm Quarterly How to cite this book chapter: Ethnersson Pontara, Johanna. “The Intersection between Film and Opera in the 1960s: Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf as an Example of Formal Imitation.” In The Power of the In-Between: Intermediality as a Tool for Aesthetic Analysis and Critical Reflection, edited by Sonya Petersson, Christer Johansson, Magdalena Holdar, and Sara Callahan, 49–74. -

Unpopular Culture and Explore Its Critical Possibilities and Ramifications from a Large Variety of Perspectives

15 mm front 153 mm 8 mm 19,9 mm 8 mm front 153 mm 15 mm 15 mm TELEVISUAL CULTURE TELEVISUAL CULTURE This collection includes eighteen essays that introduce the concept of Lüthe and Pöhlmann (eds) unpopular culture and explore its critical possibilities and ramifications from a large variety of perspectives. Proposing a third term that operates beyond the dichotomy of high culture and mass culture and yet offers a fresh approach to both, these essays address a multitude of different topics that can all be classified as unpopular culture. From David Foster Wallace and Ernest Hemingway to Zane Grey, from Christian rock and country to clack cetal, from Steven Seagal to Genesis (Breyer) P-Orridge, from K-pop to The Real Housewives, from natural disasters to 9/11, from thesis hatements to professional sports, these essays find the unpopular across media and genres, and they analyze the politics and the aesthetics of an unpopular culture (and the unpopular in culture) that has not been duly recognized as such by the theories and methods of cultural studies. Martin Lüthe is an associate professor in North American Cultural Studies at the John F. Kennedy-Institute at Freie Universität Berlin. Unpopular Culture Sascha Pöhlmann is an associate professor in American Literary History at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich. 240 mm Martin Lüthe and Sascha Pöhlmann (eds) Unpopular Culture ISBN: 978-90-8964-966-9 AUP.nl 9 789089 649669 15 mm Unpopular Culture Televisual Culture The ‘televisual’ names a media culture generally in which television’s multiple dimensions have shaped and continue to alter the coordinates through which we understand, theorize, intervene, and challenge contemporary media culture. -

Violence Against the Self in Depressive Suicidal Black Metal Owen Coggins

Article Owen Coggins Distortion, restriction and instability Distortion, restriction and instability: Violence against the self in depressive suicidal black metal Owen Coggins The Open University Owen Coggins researches violence, ambiguity and mysticism in popular music, particularly in relation to extreme music and noise. His monograph, Mysticism, Ritual and Religion in Drone Metal was published by Bloomsbury Academic in 2018, and, in addition to contributing several articles to Metal Music Studies his work has appeared in Popular Music, Implicit Religion, and Diskus: Journal of the British Association for the Study of Religion amongst others. He also runs Oaken Palace Records, a registered charity raising money for endangered species through releasing drone records. He is Honorary Associate of the Religious Studies Department at the Open University. Contact: Religious Studies Department, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK. E-mail: [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8322-1583 Abstract In the underground subgenre of depressive suicidal black metal (DSBM), extremes of violence against the self are presented in combination with a restrictive version of black metal. Album covers feature explicit photographs of self-cutting or drawings of suicide by hanging; vocals are tortured screams expressing extreme suffering, and guitar sounds are so distorted that they begin to approach an ambient atmospheric blur. Given the history of concern about metal and its health implications, I investigate DSBM as a case in which representation of harm in music is overt, explicit and extreme, yet the health impact of the music is undetermined. I discuss how different modalities of distortion and restriction may connect the sound of DSBM to themes of violence against the self, presenting a theoretical framework for approaching DSBM as music which negotiates a complex economy of the staging and control of violence with respect to the self.