The Playfulness of Ingmar Bergman: Screenwriting from Notebooks to Screenplays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Films of Ingmar Bergman: Centennial Celebration!

The Films of Ingmar Bergman: Centennial Celebration! Swedish filmmaker, author, and film director Ingmar Bergman was born in 1918, so this year will be celebrated in Sweden and around the world by those who have been captivated by his work. Bergman belongs to a group of filmmakers who were hailed as "auteurs" (authors) in the 1960s by French, then American film critics, and his work was part of a wave of "art cinema," a form that elevated "movies" to "films." In this course we will analyze in detail six films by Bergman and read short pieces by Bergman and scholars. We will discuss the concept of film authorship, Bergman's life and work, and his cinematic world. Note: some of the films to be screened contain emotionally or physically disturbing content. The films listed below should be viewed BEFORE the scheduled OLLI class. All films will be screened at the PFA Osher Theater on Wednesdays at 3-5pm, the day before the class lecture on that film. Screenings are open to the public for the usual PFA admission. All films are also available in DVD format (for purchase on Amazon and other outlets or often at libraries) or on- line through such services as FilmStruck (https://www.filmstruck.com/us/) or, in some cases, on YouTube (not as reliable). Films Week 1: 9/27 Wild Strawberries (1957, 91 mins) NOTE: screening at PFA Weds 9/25 Week 2: 10/4 The Virgin Spring (1960, 89 mins) Week 3: 10/11 Winter Light (1963, 80 mins) Week 4: 10/18 The Silence (1963, 95 mins) Week 5: 10/25 Persona (1966, 85 mins) Week 6: 11/1 Hour of the Wolf (1968, 90 mins) -

The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director

Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 19, 2009 11:55 Geoffrey Macnab writes on film for the Guardian, the Independent and Screen International. He is the author of The Making of Taxi Driver (2006), Key Moments in Cinema (2001), Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screenwriting in British Cinema (2000), and J. Arthur Rank and the British Film Industry (1993). Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director Geoffrey Macnab Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 Sheila Whitaker: Advisory Editor Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © 2009 Geoffrey Macnab The right of Geoffrey Macnab to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978 1 84885 046 0 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress -

From: Reviews and Criticism of Vietnam War Theatrical and Television Dramas ( Compiled by John K

From: Reviews and Criticism of Vietnam War Theatrical and Television Dramas (http://www.lasalle.edu/library/vietnam/FilmIndex/home.htm) compiled by John K. McAskill, La Salle University ([email protected]) P2800 EN PASSION (SWEDEN, 1969) (Other titles: Passion of Anna) Credits: director/writer, Ingmar Bergman. Cast: Liv Ullmann, Bibi Andersson, Max von Sydow, Erland Josephson. Summary: Melodrama set on a sparsely populated island in contemporary Sweden. Andreas (Sydow), a man struggling with the recent demise of his marriage and his own emotional isolation, befriends a married couple also in the midst of psychological turmoil. In turn he meets Anna (Ullmann), who is grieving the recent deaths of her husband and son. She appears zealous in her faith and steadfast in her search for truth, but gradually her delusions surface. Andreas and Anna pursue a love affair, but he is unable to overcome his feelings of deep humiliation and remains disconnected. Meanwhile, the island community is victimized by an unknown person committing acts of animal cruelty. Includes Vietnam War references. Arecco, Sergio. “Bergman - rito a passione” Filmcritica 22/212 (Jan 1971), p. 48-54. Armstrong, Marion. “Movie: Prolonged anguish” Christian century 87/47 (Nov 23, 1970), p. 1426-7. Bergman, Ingmar. Bergman on Bergman: interviews with Ingmar Bergman New York : Simon and Schuster, 1975. (p. 253-64+) _____________. Images: my life in film New York : Arcade Pub., 1994. (p. 304-10) _____________. “The passion of Anna” in Four stories of Ingmar Bergman London : M. Boyars ; New York : Doubleday, 1976. [Reissued, New York : Anchor Books, 1977] Bjorkman, Stig. “En passion” Chaplin 11 (1969), p. -

Intermediality As a Tool for Aesthetic Analysis and Critical Reflection, Edited by Sonya Petersson, Christer Johansson, Magdalena Holdar, and Sara Callahan, 49–74

The Intersection between Film and Opera in the 1960s: Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf as an Example of Formal Imitation Johanna Ethnersson Pontara Abstract The topic of this article is the intersection between media genres in 1960s Sweden. In a case study of Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf (1968) it is shown how the music contributes to intermedial qualities through the film’s connection with opera. It is argued that the film, by how the music is related to sound effects and images, can be seen as an example of formal imitation. The imitation of opera is created through technical media of film, such as fore- grounding of media in the audio-visual space, and manipulations of sounds, music, and images. Of special interest is how, by alter- nating between synchronicity and counterpoint between images, sound effects, and music, Bergman attracts attention to the media as visual and sonic experiences and creates formal structures that deviate from the overall character of the film. The intermedial di- mension of the film revealed by the analysis is contextualized in re- lation to the historical discussion of mixed versus pure medialities. The film is seen in the light of an interest in media genre mixedness versus media genre specificity in 1960s Sweden. Introduction In a review of Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf (Vargtimmen, 1968) published in the American film journalFilm Quarterly How to cite this book chapter: Ethnersson Pontara, Johanna. “The Intersection between Film and Opera in the 1960s: Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf as an Example of Formal Imitation.” In The Power of the In-Between: Intermediality as a Tool for Aesthetic Analysis and Critical Reflection, edited by Sonya Petersson, Christer Johansson, Magdalena Holdar, and Sara Callahan, 49–74. -

Drama Movies

Libraries DRAMA MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 42 DVD-5254 12 DVD-1200 70's DVD-0418 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 8 1/2 DVD-3832 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 8 1/2 c.2 DVD-3832 c.2 127 Hours DVD-8008 8 Mile DVD-1639 1776 DVD-0397 9th Company DVD-1383 1900 DVD-4443 About Schmidt DVD-9630 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 Accused DVD-6182 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 1 Ace in the Hole DVD-9473 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 1 Across the Universe DVD-5997 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adam Bede DVD-7149 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adjustment Bureau DVD-9591 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs 1 Admiral DVD-7558 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs 5 Adventures of Don Juan DVD-2916 25th Hour DVD-2291 Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert DVD-4365 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 Advise and Consent DVD-1514 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 Affair to Remember DVD-1201 3 Women DVD-4850 After Hours DVD-3053 35 Shots of Rum c.2 DVD-4729 c.2 Against All Odds DVD-8241 400 Blows DVD-0336 Age of Consent (Michael Powell) DVD-4779 DVD-8362 Age of Innocence DVD-6179 8/30/2019 Age of Innocence c.2 DVD-6179 c.2 All the King's Men DVD-3291 Agony and the Ecstasy DVD-3308 DVD-9634 Aguirre: The Wrath of God DVD-4816 All the Mornings of the World DVD-1274 Aladin (Bollywood) DVD-6178 All the President's Men DVD-8371 Alexander Nevsky DVD-4983 Amadeus DVD-0099 Alfie DVD-9492 Amar Akbar Anthony DVD-5078 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul DVD-4725 Amarcord DVD-4426 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul c.2 DVD-4725 c.2 Amazing Dr. -

Timeline of Selected Bergman 100 Events

London, 18.09.17 Timeline of selected Bergman 100 events This timeline includes major activities before and during the Bergman year. Please note that there are many more events to be announced both within this timeframe and beyond. A full, regularly updated calendar of performances, retrospectives, exhibitions and other events is available at www.ingmarbergman.se September 2017 • Misc.: Launch of Bergman 100, 18 Sep, London, UK. • On stage: Scenes from a marriage, opening 31 Aug, Det Kgl Teater (The Royal Playhouse), Copenhagen, Denmark. • On stage: Autumn Sonata (opera), opening 8 Sep, Finnish National Opera, Helsinki, Finland. • Book release: Ingmar Bergman A–Ö (in English), Ingmar Bergman Foundation/Norstedts publishing, Sweden. • On stage: The Best Intentions, opening 16 Sep, Aarhus theatre, Aarhus, Denmark. • On stage: After the Rehearsal/Persona, The Barbican, London, UK. • On stage: Scenes From a Marriage, opening 20 Sep, Teatros del Canal, Madrid, Spain. • On stage: Breathe, Bergman-inspired dance performance, opening 28 Sep, Inkonst, Malmö, Sweden. • On stage: The Serpent’s Egg, opening 30 Sep, Cuvilliés-Theater, Munich, Germany. • On stage: Scenes From a Marriage, world tour Sep–Dec, Asia, Europe, South America. October 2017 • On stage: Scenes from a marriage, opening 5 Oct, Ernst-Deutsch-Theater, Hamburg, Germany. • On stage: After the rehearsal, opening 20 Oct, Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus, Düsseldorf, Germany. • Misc.: The European Film Academy awards Hovs Hallar the title ‘Treasure of European Film Culture’. (A nature reserve in the county of Skåne, Sweden, Hovs Hallar is the location of the chess scene in The Seventh Seal.) • On stage: Scenes From a Marriage, opening 25 Oct, Teatro Tivoli, Barcelona, Spain. -

Music As Spiritual Metaphor in the Cinema of Ingmar Bergman

Music as Spiritual Metaphor in the Cinema of Ingmar Bergman By Michael Bird Spring 1996 Issue of KINEMA SECRET ARITHMETIC OF THE SOUL: MUSIC AS SPIRITUAL METAPHOR IN THE CINEMA OF INGMAR BERGMAN Prelude: General Reflections on Music and the Sacred: It frequently happens that in listening to a piece of music we at first do not hear the deep, fundamental tone, the sure stride of the melody, on which everything else is built... It is only after we have accustomed our ear that we find law and order, and as with one magical stroke, a single unified world emerges from the confused welter of sounds. And when this happens, we suddenly realize with delight and amazement that the fundamental tone was also resounding before, that all along the melody had been giving order and unity... - Rudolf Bultmann(1) I said to myself, it is as if the eternal harmony were conversing within itself, as it may have done in the bosom of God just before the Creation of the world. So likewise did it move in my inmost soul. - Goethe(2) One Sunday in December, I was listening to Bach’s Christmas Oratorio in Hedvig Eleonora Church... The chorale moved confidentially through the darkening church: Bach’s piety heals the torment of our faithlessness... - Ingmar Bergman(3) Ingmar Bergman has frequently indicated the immense significance of musical experience for his own personal and artistic development, just as he has also suggested that human existence at large has need for music. His words suggest that of all arts, music may be the most spiritually meaningful of all. -

Columbia University Spring 2004 Tentative Syllabus Swedish-Comp

Columbia University Spring 2004 Tentative Syllabus Swedish-Comp. Lit. W3270 Ingmar Bergman and the Development of Scandinavian Film Instructor: Verne Moberg Phone: 212/854-4015 (office) Time: 11:00-3:00 P.M., Fridays Office: 415 Hamilton Hall E-mail: [email protected] Place: 717 Hamilton Hall Office Hours: by appointment Purpose: To explore the growth of the various film traditions in Scandinavia, ranging from the introduction of silent film through the landmark contributions of Ingmar Bergman in Sweden over many decades, with Carl Dreyer and more recent directors in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Course Literature Print Texts: Handouts will be available on silent films, the films of Carl Dreyer, and basics about Ingmar Bergman. All students are required to read and study at least one of the following works by Bergman: Images: My Life in Film ( Arcade, NY, 1990); The Magic Lantern, his autobiography (Penguin, NY, 1987); or Sunday’s Children (1993). Also required reading are two of the following works about Bergman: Ingmar Bergman: An Artist’s Journey--on Stage, on Screen, in Print, edited by Roger W. Oliver (Arcade, NY, 1995); Gender and Representation in the Films of Ingmar Bergman by Marilyn Blackwell (Camden House, Columbia, S.C., 1997); Ingmar Bergman: The Art of Confession, by Hubert I. Cohen (Twayne Publishers, NY, 1993); and Between Stage and Screen: Ingmar Bergman Directs by Egil Törnquist (Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 1995). More information about Bergman can be found on the Internet in English and Swedish at <http://www.hem.passagen.se/vogler>. Other required reading includes handouts on later directors and Film in Sweden edited by Francesco Bono and Maaret Koskinen (Swedish Institute, Stockholm, 1997). -

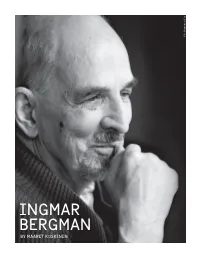

Ingmar Bergman by Maaret-Koskinen English.Pdf

Foto: Bengt Wanselius Foto: INGMAR BERGMAN BY MAARET KOSKINEN Ingmar Bergman by Maaret Koskinen It is now, in the year of 2018, almost twenty years ago that Ingmar Bergman asked me to “take a look at his hellofamess” in his private library at his residence on Fårö, the small island in the Baltic Sea where he shot many of his films from the 1960s on, and where he lived until his death in 2007, at the age of 89. S IT turned out, this question, thrown foremost filmmaker of all time, but is generally re Aout seemingly spontaneously, was highly garded as one of the foremost figures in the entire premeditated on Bergman’s part. I soon came to history of the cinematic arts. In fact, Bergman is understand that his aim was to secure his legacy for among a relatively small, exclusive group of film the future, saving it from being sold off to the highest makers – a Fellini, an Antonioni, a Tarkovsky – whose paying individual or institution abroad. Thankfully, family names rarely need to be accompanied by a Bergman’s question eventually resulted in Bergman given name: “Bergman” is a concept, a kind of “brand donating his archive in its entirety, which in 2007 name” in itself. was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List, and the subsequent formation of the Ingmar Bergman Bergman’s career as a cinematic artist is unique in Foundation (www.ingmarbergman.se). its sheer volume. From his directing debut in Crisis (1946) to Fanny and Alexander (1982), he found time The year of 2018 is also the commemoration of to direct more than 40 films, including some – for Bergman’s birth year of 1918. -

Ingmar Bergman Roland Pöntinen

INGMAR BERGMAN MUSIC FROM THE FILMS ROLAND PÖNTINEN piano BIS-2377 STENHAMMAR QUARTET | TORLEIF THEDÉEN cello Ingmar Bergman – Music From the Films 1 J.S. Bach: Sarabande from Cello Suite No.5 in C minor, BWV1011 3'47 Viskningar och rop & Saraband [Cries and Whispers & Saraband] 2 Robert Schumann: Aufschwung from Fantasiestücke, Op.12 3'17 Musik i mörker & Sommarnattens leende [Music in Darkness & Smiles of a Summer Night] 3 Frédéric Chopin: Nocturne in C sharp minor, Op.27 No.1 5'04 Fanny och Alexander [Fanny and Alexander] 4 Frédéric Chopin: Prelude in D minor, Op.28 No.24 2'36 Musik i mörker 5 J.S. Bach: Sarabande from Cello Suite No.4 in E flat major, BWV1010 5'02 Höstsonaten [Autumn Sonata] 6 W.A. Mozart: Fantasy in C minor, K 475 12'26 Ansikte mot ansikte [Face to Face] 7 Frédéric Chopin: Mazurka in A minor, Op.17 No.4 3'43 Viskningar och rop 8 Franz Schubert: Andante sostenuto 9'37 Second movement of Sonata in B flat major, D 960 Larmar och gör sig till [In the Presence of a Clown] 2 9 Domenico Scarlatti: Sonata in D major, K 535 3'11 Djävulens öga [The Devil’s Eye] 10 Frédéric Chopin: Prelude in A minor, Op.28 No.2 2'17 Höstsonaten 11 Domenico Scarlatti: Sonata in E major, K 380 4'18 Djävulens öga 12 J.S. Bach: Variation 25 from Goldberg Variations, BWV988 6'39 Tystnaden [The Silence] 13 J.S. Bach: Sarabande from Cello Suite No.2 in D minor, BWV1008 5'43 Såsom i en spegel [Through a Glass Darkly] 14 Robert Schumann: In modo d’una marcia 8'44 Second movement of Piano Quintet in E flat major, Op.44 Fanny och Alexander TT: 78'28 Roland Pöntinen piano Stenhammar Quartet [Schumann: Piano Quintet] Peter Olofsson & Per Öman violins · Tony Bauer viola · Mats Olofsson cello Torleif Thedéen cello [Bach: Sarabandes] 3 Tystnaden (1963) Gunnel Lindblom and Jörgen Lindström as Anna and her son Johan © 1963 AB Svensk Filmindustri. -

Scandinavian S327

GSD 331C (37145)/CL 323 (33430)/EUS 347 (35520) Prof. Lynn Wilkinson Fall 2019 The Films of Ingmar Bergman Ingmar Bergman (1918-2007) was arguably the greatest filmmaker of the twentieth century. His career spanned over sixty years and includes such works as the sophisticated comedy Smiles of a Summer Night (1955), the allegorical Seventh Seal (1957), the avant-garde Persona (1966), the masterful television adaptation of Mozart’s The Magic Flute (1975), and the television miniseries Fanny and Alexander (1982). He also wrote scripts for many other filmmakers, including Bille August and Liv Ullmann. In 2003, he directed the television film Saraband, and in recent years many of his films have been adapted for the stage both in Sweden and elsewhere. This course is intended as an introduction both to the films of Ingmar Bergman and to the viewing of films in general. We will look at representative films by this prolific and gifted filmmaker, considering them in the contexts of the director's life, Scandinavian culture, and issues of film theory and aesthetics. This course carries the Writing Flag. Writing Flag courses are designed to give students experience with writing in an academic discipline. In this class, you can expect to write regularly during the semester, complete substantial writing projects, and receive feedback from your instructor to help you improve your writing. You will also have the opportunity to revise one or more assignments, and to read and discuss your peers' work. You should therefore expect a substantial portion of your grade to come from your written work. -

The Sensation of Time in Ingmar Bergman's Poetics of Bodies And

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 8 (2014) 41–58 DOI: 10.2478/ausfm-2014-0025 The Sensation of Time in Ingmar Bergman’s Poetics of Bodies and Minds Fabio Pezzetti Tonion Museo Nazionale del Cinema (Torino) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Bergman’s cinema does more than just focus on a personal rem ection of the body as an emotive and emotional vector; his cinema, through the transitory fragility of the human body as represented by his actors, del nes the possibilities of a perceptive horizon in which the experience of passing time becomes tangible. Even though the Swedish director’s entire opus is traversed by this rem ection, it is particularly evident in the l lms he made during the 1960s, in which the “room-sized” dimension of the sets permits a higher concentration of space and time. In this “concentration,” in this claustrophobic dimension in which Bergman forces his characters to exist, there is an often inm ammable accumulation of affections and emotions searching for release through human contact which is often frustrated, denied, and/or impossible. This situation creates characters who act according to solipsistic directives, in whom physiological and mental traits are fused together, and the notion of phenomenological reality is cancelled out and supplanted by aspects of dreamlike hallucinations, phantasmagorical creations, and psychic drifting. Starting from Hour of the Wolf, this essay highlights the process through which, by l xing in images the physicality of his characters’ sensations, Bergman del nes a complex temporal horizon, in which the phenomenological dimension of the linear passage of time merges with, and often turns into, a subjective perception of passing time, creating a synchretic relationship between the quantitative time of the action and the qualitative time of the sensation.