10.1101/2020.07.29.227421; This Version Posted July 30, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Placenta Exosomes: Biogenesis, Isolation, Composition, and Prospects for Use in Diagnostics

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Human Placenta Exosomes: Biogenesis, Isolation, Composition, and Prospects for Use in Diagnostics Evgeniya E. Burkova 1,* , Sergey E. Sedykh 1,2 and Georgy A. Nevinsky 1,2 1 SB RAS Institute of Chemical Biology and Fundamental Medicine, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia; [email protected] (S.E.S.); [email protected] (G.A.N.) 2 Department of Natural Sciences, Novosibirsk State University, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-(383)-363-51-27 Abstract: Exosomes are 40–100 nm nanovesicles participating in intercellular communication and transferring various bioactive proteins, mRNAs, miRNAs, and lipids. During pregnancy, the placenta releases exosomes into the maternal circulation. Placental exosomes are detected in the maternal blood even in the first trimester of pregnancy and their numbers increase significantly by the end of pregnancy. Exosomes are necessary for the normal functioning of the placenta and fetal development. Effects of exosomes on target cells depend not only on their concentration but also on their intrinsic components. The biochemical composition of the placental exosomes may cause various complications of pregnancy. Some studies relate the changes in the composition of nanovesicles to placental dysfunction. Isolation of placental exosomes from the blood of pregnant women and the study of protein, lipid, and nucleic composition can lead to the development of methods for early diagnosis of pregnancy pathologies. This review describes the biogenesis of exosomes, methods Citation: Burkova, E.E.; Sedykh, S.E.; of their isolation, analyzes their biochemical composition, and considers the prospects for using Nevinsky, G.A. Human Placenta exosomes to diagnose pregnancy pathologies. -

Fungal Evolution: Major Ecological Adaptations and Evolutionary Transitions

Biol. Rev. (2019), pp. 000–000. 1 doi: 10.1111/brv.12510 Fungal evolution: major ecological adaptations and evolutionary transitions Miguel A. Naranjo-Ortiz1 and Toni Gabaldon´ 1,2,3∗ 1Department of Genomics and Bioinformatics, Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG), The Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology, Dr. Aiguader 88, Barcelona 08003, Spain 2 Department of Experimental and Health Sciences, Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), 08003 Barcelona, Spain 3ICREA, Pg. Lluís Companys 23, 08010 Barcelona, Spain ABSTRACT Fungi are a highly diverse group of heterotrophic eukaryotes characterized by the absence of phagotrophy and the presence of a chitinous cell wall. While unicellular fungi are far from rare, part of the evolutionary success of the group resides in their ability to grow indefinitely as a cylindrical multinucleated cell (hypha). Armed with these morphological traits and with an extremely high metabolical diversity, fungi have conquered numerous ecological niches and have shaped a whole world of interactions with other living organisms. Herein we survey the main evolutionary and ecological processes that have guided fungal diversity. We will first review the ecology and evolution of the zoosporic lineages and the process of terrestrialization, as one of the major evolutionary transitions in this kingdom. Several plausible scenarios have been proposed for fungal terrestralization and we here propose a new scenario, which considers icy environments as a transitory niche between water and emerged land. We then focus on exploring the main ecological relationships of Fungi with other organisms (other fungi, protozoans, animals and plants), as well as the origin of adaptations to certain specialized ecological niches within the group (lichens, black fungi and yeasts). -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Edgar et al. 10.1073/pnas.1601895113 SI Methods (Actimetrics), and recordings were analyzed using LumiCycle Mice. Sample size was determined using the resource equation: Data Analysis software (Actimetrics). E (degrees of freedom in ANOVA) = (total number of exper- – Cell Cycle Analysis of Confluent Cell Monolayers. NIH 3T3, primary imental animals) (number of experimental groups), with −/− sample size adhering to the condition 10 < E < 20. For com- WT, and Bmal1 fibroblasts were sequentially transduced − − parison of MuHV-4 and HSV-1 infection in WT vs. Bmal1 / with lentiviral fluorescent ubiquitin-based cell cycle indicators mice at ZT7 (Fig. 2), the investigator did not know the genotype (FUCCI) mCherry::Cdt1 and amCyan::Geminin reporters (32). of the animals when conducting infections, bioluminescence Dual reporter-positive cells were selected by FACS (Influx Cell imaging, and quantification. For bioluminescence imaging, Sorter; BD Biosciences) and seeded onto 35-mm dishes for mice were injected intraperitoneally with endotoxin-free lucif- subsequent analysis. To confirm that expression of mCherry:: Cdt1 and amCyan::Geminin correspond to G1 (2n DNA con- erin (Promega E6552) using 2 mg total per mouse. Following < ≤ anesthesia with isofluorane, they were scanned with an IVIS tent) and S/G2 (2 n 4 DNA content) cell cycle phases, Lumina (Caliper Life Sciences), 15 min after luciferin admin- respectively, cells were stained with DNA dye DRAQ5 (abcam) and analyzed by flow cytometry (LSR-Fortessa; BD Biosci- istration. Signal intensity was quantified using Living Image ences). To examine dynamics of replicative activity under ex- software (Caliper Life Sciences), obtaining maximum radiance perimental confluent conditions, synchronized FUCCI reporter for designated regions of interest (photons per second per − − − monolayers were observed by time-lapse live cell imaging over square centimeter per Steradian: photons·s 1·cm 2·sr 1), relative 3 d (Nikon Eclipse Ti-E inverted epifluorescent microscope). -

Diseases of Trees in the Great Plains

United States Department of Agriculture Diseases of Trees in the Great Plains Forest Rocky Mountain General Technical Service Research Station Report RMRS-GTR-335 November 2016 Bergdahl, Aaron D.; Hill, Alison, tech. coords. 2016. Diseases of trees in the Great Plains. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-335. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 229 p. Abstract Hosts, distribution, symptoms and signs, disease cycle, and management strategies are described for 84 hardwood and 32 conifer diseases in 56 chapters. Color illustrations are provided to aid in accurate diagnosis. A glossary of technical terms and indexes to hosts and pathogens also are included. Keywords: Tree diseases, forest pathology, Great Plains, forest and tree health, windbreaks. Cover photos by: James A. Walla (top left), Laurie J. Stepanek (top right), David Leatherman (middle left), Aaron D. Bergdahl (middle right), James T. Blodgett (bottom left) and Laurie J. Stepanek (bottom right). To learn more about RMRS publications or search our online titles: www.fs.fed.us/rm/publications www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/ Background This technical report provides a guide to assist arborists, landowners, woody plant pest management specialists, foresters, and plant pathologists in the diagnosis and control of tree diseases encountered in the Great Plains. It contains 56 chapters on tree diseases prepared by 27 authors, and emphasizes disease situations as observed in the 10 states of the Great Plains: Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming. The need for an updated tree disease guide for the Great Plains has been recog- nized for some time and an account of the history of this publication is provided here. -

Biology of Fungi, Lecture 2: the Diversity of Fungi and Fungus-Like Organisms

Biology of Fungi, Lecture 2: The Diversity of Fungi and Fungus-Like Organisms Terms You Should Understand u ‘Fungus’ (pl., fungi) is a taxonomic term and does not refer to morphology u ‘Mold’ is a morphological term referring to a filamentous (multicellular) condition u ‘Mildew’ is a term that refers to a particular type of mold u ‘Yeast’ is a morphological term referring to a unicellular condition Special Lecture Notes on Fungal Taxonomy u Fungal taxonomy is constantly in flux u Not one taxonomic scheme will be agreed upon by all mycologists u Classical fungal taxonomy was based primarily upon morphological features u Contemporary fungal taxonomy is based upon phylogenetic relationships Fungi in a Broad Sense u Mycologists have traditionally studied a diverse number of organisms, many not true fungi, but fungal-like in their appearance, physiology, or life style u At one point, these fungal-like microbes included the Actinomycetes, due to their filamentous growth patterns, but today are known as Gram-positive bacteria u The types of organisms mycologists have traditionally studied are now divided based upon phylogenetic relationships u These relationships are: Q Kingdom Fungi - true fungi Q Kingdom Straminipila - “water molds” Q Kingdom Mycetozoa - “slime molds” u Kingdom Fungi (Mycota) Q Phylum: Chytridiomycota Q Phylum: Zygomycota Q Phylum: Glomeromycota Q Phylum: Ascomycota Q Phylum: Basidiomycota Q Form-Phylum: Deuteromycota (Fungi Imperfecti) Page 1 of 16 Biology of Fungi Lecture 2: Diversity of Fungi u Kingdom Straminiplia (Chromista) -

A Chemical Proteomic Approach to Investigate Rab Prenylation in Living Systems

A chemical proteomic approach to investigate Rab prenylation in living systems By Alexandra Fay Helen Berry A thesis submitted to Imperial College London in candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Imperial College. Department of Chemistry Imperial College London Exhibition Road London SW7 2AZ August 2012 Declaration of Originality I, Alexandra Fay Helen Berry, hereby declare that this thesis, and all the work presented in it, is my own and that it has been generated by me as the result of my own original research, unless otherwise stated. 2 Abstract Protein prenylation is an important post-translational modification that occurs in all eukaryotes; defects in the prenylation machinery can lead to toxicity or pathogenesis. Prenylation is the modification of a protein with a farnesyl or geranylgeranyl isoprenoid, and it facilitates protein- membrane and protein-protein interactions. Proteins of the Ras superfamily of small GTPases are almost all prenylated and of these the Rab family of proteins forms the largest group. Rab proteins are geranylgeranylated with up to two geranylgeranyl groups by the enzyme Rab geranylgeranyltransferase (RGGT). Prenylation of Rabs allows them to locate to the correct intracellular membranes and carry out their roles in vesicle trafficking. Traditional methods for probing prenylation involve the use of tritiated geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate which is hazardous, has lengthy detection times, and is insufficiently sensitive. The work described in this thesis developed systems for labelling Rabs and other geranylgeranylated proteins using a technique known as tagging-by-substrate, enabling rapid analysis of defective Rab prenylation in cells and tissues. An azide analogue of the geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate substrate of RGGT (AzGGpp) was applied for in vitro prenylation of Rabs by recombinant enzyme. -

9B Taxonomy to Genus

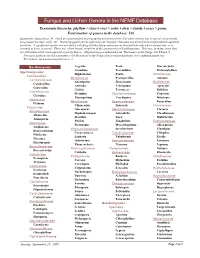

Fungus and Lichen Genera in the NEMF Database Taxonomic hierarchy: phyllum > class (-etes) > order (-ales) > family (-ceae) > genus. Total number of genera in the database: 526 Anamorphic fungi (see p. 4), which are disseminated by propagules not formed from cells where meiosis has occurred, are presently not grouped by class, order, etc. Most propagules can be referred to as "conidia," but some are derived from unspecialized vegetative mycelium. A significant number are correlated with fungal states that produce spores derived from cells where meiosis has, or is assumed to have, occurred. These are, where known, members of the ascomycetes or basidiomycetes. However, in many cases, they are still undescribed, unrecognized or poorly known. (Explanation paraphrased from "Dictionary of the Fungi, 9th Edition.") Principal authority for this taxonomy is the Dictionary of the Fungi and its online database, www.indexfungorum.org. For lichens, see Lecanoromycetes on p. 3. Basidiomycota Aegerita Poria Macrolepiota Grandinia Poronidulus Melanophyllum Agaricomycetes Hyphoderma Postia Amanitaceae Cantharellales Meripilaceae Pycnoporellus Amanita Cantharellaceae Abortiporus Skeletocutis Bolbitiaceae Cantharellus Antrodia Trichaptum Agrocybe Craterellus Grifola Tyromyces Bolbitius Clavulinaceae Meripilus Sistotremataceae Conocybe Clavulina Physisporinus Trechispora Hebeloma Hydnaceae Meruliaceae Sparassidaceae Panaeolina Hydnum Climacodon Sparassis Clavariaceae Polyporales Gloeoporus Steccherinaceae Clavaria Albatrellaceae Hyphodermopsis Antrodiella -

The Phylogeny of Plant and Animal Pathogens in the Ascomycota

Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology (2001) 59, 165±187 doi:10.1006/pmpp.2001.0355, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on MINI-REVIEW The phylogeny of plant and animal pathogens in the Ascomycota MARY L. BERBEE* Department of Botany, University of British Columbia, 6270 University Blvd, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada (Accepted for publication August 2001) What makes a fungus pathogenic? In this review, phylogenetic inference is used to speculate on the evolution of plant and animal pathogens in the fungal Phylum Ascomycota. A phylogeny is presented using 297 18S ribosomal DNA sequences from GenBank and it is shown that most known plant pathogens are concentrated in four classes in the Ascomycota. Animal pathogens are also concentrated, but in two ascomycete classes that contain few, if any, plant pathogens. Rather than appearing as a constant character of a class, the ability to cause disease in plants and animals was gained and lost repeatedly. The genes that code for some traits involved in pathogenicity or virulence have been cloned and characterized, and so the evolutionary relationships of a few of the genes for enzymes and toxins known to play roles in diseases were explored. In general, these genes are too narrowly distributed and too recent in origin to explain the broad patterns of origin of pathogens. Co-evolution could potentially be part of an explanation for phylogenetic patterns of pathogenesis. Robust phylogenies not only of the fungi, but also of host plants and animals are becoming available, allowing for critical analysis of the nature of co-evolutionary warfare. Host animals, particularly human hosts have had little obvious eect on fungal evolution and most cases of fungal disease in humans appear to represent an evolutionary dead end for the fungus. -

<I>Neolecta Vitellina

ISSN (print) 0093-4666 © 2011. Mycotaxon, Ltd. ISSN (online) 2154-8889 MYCOTAXON http://dx.doi.org/10.5248/118.197 Volume 118, pp. 197–201 October–December 2011 Neolecta vitellina, first record from Romania, with notes on habitat and phenology Vasilică Claudiu Chinan 1* & David Hewitt 2 1Faculty of Biology, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, Bd. Carol I, No. 20A, 700505, Iaşi, Romania 2Department of Botany, Academy of Natural Sciences 1900 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, PA 19103 USA * Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract — Neolecta vitellina, one of the rarely collected ascomycete species in Europe, is reported from Romania for the first time. The species was found on the ground, under Norway spruce (Picea abies) in 2004, from the Nature Reserve “Tinovul Mare” Poiana Stampei (Eastern Carpathians, Romania). Subsequent field observations have confirmed the presence of Neolecta vitellina in the same location, in the period 2005–10. A description and photographs of the specimens are presented. Key words — Ascomycota, Neolectaceae, ITS sequence Introduction The genus Neolecta Speg. belongs to the ascomycete family Neolectaceae (Redhead 1977), order Neolectales (Landvik et al. 1993), class Neolectomycetes (Taphrinomycotina, Ascomycota). This genus includes three accepted species —N. flavovirescens Speg., N. irregularis (Peck) Korf & J.K. Rogers, N. vitellina— with clavate, unbranched to lobed yellow ascomata, up to about 7 cm tall (Landvik et al. 2003). Of these three species, only N. vitellina has been reported from Europe (Bresadola 1882, Geitler 1958, Hansen & Knudsen 2000: 48–50, Krieglsteiner 1993: 421, Landvik et al. 2003, Ohenoja 1975, Redhead 1989). Work published by European researchers about Neolecta vitellina refers mainly to phylogeny, morphology and ultrastructure (Landvik 1996, 1998; Landvik et al. -

Literature Mining Sustains and Enhances Knowledge Discovery from Omic Studies

LITERATURE MINING SUSTAINS AND ENHANCES KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM OMIC STUDIES by Rick Matthew Jordan B.S. Biology, University of Pittsburgh, 1996 M.S. Molecular Biology/Biotechnology, East Carolina University, 2001 M.S. Biomedical Informatics, University of Pittsburgh, 2005 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Medicine in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF MEDICINE This dissertation was presented by Rick Matthew Jordan It was defended on December 2, 2015 and approved by Shyam Visweswaran, M.D., Ph.D., Associate Professor Rebecca Jacobson, M.D., M.S., Professor Songjian Lu, Ph.D., Assistant Professor Dissertation Advisor: Vanathi Gopalakrishnan, Ph.D., Associate Professor ii Copyright © by Rick Matthew Jordan 2016 iii LITERATURE MINING SUSTAINS AND ENHANCES KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM OMIC STUDIES Rick Matthew Jordan, M.S. University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Genomic, proteomic and other experimentally generated data from studies of biological systems aiming to discover disease biomarkers are currently analyzed without sufficient supporting evidence from the literature due to complexities associated with automated processing. Extracting prior knowledge about markers associated with biological sample types and disease states from the literature is tedious, and little research has been performed to understand how to use this knowledge to inform the generation of classification models from ‘omic’ data. Using pathway analysis methods to better understand the underlying biology of complex diseases such as breast and lung cancers is state-of-the-art. However, the problem of how to combine literature- mining evidence with pathway analysis evidence is an open problem in biomedical informatics research. -

Orbilia Ultrastructure, Character Evolution and Phylogeny of Pezizomycotina

Mycologia, 104(2), 2012, pp. 462–476. DOI: 10.3852/11-213 # 2012 by The Mycological Society of America, Lawrence, KS 66044-8897 Orbilia ultrastructure, character evolution and phylogeny of Pezizomycotina T.K. Arun Kumar1 INTRODUCTION Department of Plant Biology, University of Minnesota, St Paul, Minnesota 55108 Ascomycota is a monophyletic phylum (Lutzoni et al. 2004, James et al. 2006, Spatafora et al. 2006, Hibbett Rosanne Healy et al. 2007) comprising three subphyla, Taphrinomy- Department of Plant Biology, University of Minnesota, cotina, Saccharomycotina and Pezizomycotina (Su- St Paul, Minnesota 55108 giyama et al. 2006, Hibbett et al. 2007). Taphrinomy- Joseph W. Spatafora cotina, according to the current classification (Hibbett Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon et al. 2007), consists of four classes, Neolectomycetes, State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Pneumocystidiomycetes, Schizosaccharomycetes, Ta- phrinomycetes, and an unplaced genus, Saitoella, Meredith Blackwell whose members are ecologically and morphologically Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70803 highly diverse (Sugiyama et al. 2006). Soil Clone Group 1, poorly known from geographically wide- David J. McLaughlin spread environmental samples and a single culture, Department of Plant Biology, University of Minnesota, was suggested as a fourth subphylum (Porter et al. St Paul, Minnesota 55108 2008). More recently however the group has been described as a new class of Taphrinomycotina, Archae- orhizomycetes (Rosling et al. 2011), based primarily on Abstract: Molecular phylogenetic analyses indicate information from rRNA sequences. The mode of that the monophyletic classes Orbiliomycetes and sexual reproduction in Taphrinomycotina is ascogen- Pezizomycetes are among the earliest diverging ous without the formation of ascogenous hyphae, and branches of Pezizomycotina, the largest subphylum except for the enigmatic, apothecium-producing of the Ascomycota. -

Fungal Phyla

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Sydowia Jahr/Year: 1984 Band/Volume: 37 Autor(en)/Author(s): Arx Josef Adolf, von Artikel/Article: Fungal phyla. 1-5 ©Verlag Ferdinand Berger & Söhne Ges.m.b.H., Horn, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Fungal phyla J. A. von ARX Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, P. O. B. 273, NL-3740 AG Baarn, The Netherlands 40 years ago I learned from my teacher E. GÄUMANN at Zürich, that the fungi represent a monophyletic group of plants which have algal ancestors. The Myxomycetes were excluded from the fungi and grouped with the amoebae. GÄUMANN (1964) and KREISEL (1969) excluded the Oomycetes from the Mycota and connected them with the golden and brown algae. One of the first taxonomist to consider the fungi to represent several phyla (divisions with unknown ancestors) was WHITTAKER (1969). He distinguished phyla such as Myxomycota, Chytridiomycota, Zygomy- cota, Ascomycota and Basidiomycota. He also connected the Oomycota with the Pyrrophyta — Chrysophyta —• Phaeophyta. The classification proposed by WHITTAKER in the meanwhile is accepted, e. g. by MÜLLER & LOEFFLER (1982) in the newest edition of their text-book "Mykologie". The oldest fungal preparation I have seen came from fossil plant material from the Carboniferous Period and was about 300 million years old. The structures could not be identified, and may have been an ascomycete or a basidiomycete. It must have been a parasite, because some deformations had been caused, and it may have been an ancestor of Taphrina (Ascomycota) or of Milesina (Uredinales, Basidiomycota).