Schubert's Instrumental Interpretation of His Lieder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesis and the Work Presented in It Is Entirely My Own

! ! ! ! ! Christopher Tarrant! Royal Holloway, University! of London! ! ! Schubert, Sonata Theory, Psychoanalysis: ! Traversing the Fantasy in Schubert’s Sonata Forms! ! ! Submission for the Degree of Ph.D! March! 2015! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "1 ! Declaration of! Authorship ! ! I, Christopher Tarrant, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stat- !ed. ! ! ! Signed: ______________________ ! Date: March 3, 2015# "2 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! For Mum and Dad "3 Acknowledgements! ! This project grew out of a fascination with Schubert’s music and the varied ways of analysing it that I developed as an undergraduate at Lady Margaret Hall, University of Oxford. It was there that two Schubert scholars, Suzannah Clark and Susan Wollen- berg, gave me my first taste of the beauties, the peculiarities, and the challenges that Schubert’s music can offer. Having realised by the end of the course that there was a depth of study that this music repays, and that I had only made the most modest of scratches into its surface, I decided that the only way to satisfy the curiosity they had aroused in me was to continue studying the subject as a postgraduate.! ! It was at Royal Holloway that I began working with my supervisor, Paul Harper-Scott, to whom I owe a great deal. Under his supervision I was not only introduced to Hep- okoskian analysis and Sonata Theory, which forms the basis of this thesis, but also a bewildering array of literary theory that sparked my imagination in ways that I could never have foreseen. -

Pinchas Zukerman, Violin & Viola Yefim Bronfman, Piano

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS Tuesday, April 8, 2014, 8pm First Congregational Church Pinchas Zukerman, violin & viola Yefim Bronfman, piano PROGRAM Franz Schubert (1797–1828) Sonatina No. 2 for Violin and Piano in A minor, D. 385 (1816) Allegro moderato Andante Menuetto: Allegro Allegro Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) Sonata No. 7 for Piano and Violin in C minor, Op. 30, No. 2 (1802) Allegro con brio Adagio cantabile Scherzo: Allegro Finale: Allegro INTERMISSION Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) Sonata for Viola and Piano in F minor, Op. 120, No. 1 (1894) Allegro appassionato Andante un poco Adagio Allegretto grazioso Vivace Funded, in part, by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ – Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. This performance is made possible, in part, by Paton Sponsors Diana Cohen and Bill Falik. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. PLAYBILL PROGRAM NOTES Franz Schubert (9>@>–9?:?) tions for voice and keyboard that could be used Sonatina No. : for Violin and Piano in to support his application, but his works for vi - A minor, D. ;?= olin had all been within an orchestral or cham - ber ensemble context. He was trained in violin Composed in 1816. (though he preferred playing viola in the Schubert household quartet and in the amateur Between 1814 and 1816, Schubert worked as orchestra that sprouted from it), but he had not a teacher in his father’s school in suburban yet written a piece featuring the instrument, so Vienna. He cared little for the situation, and in March and April 1816 he quickly composed soothed his frustration by composing; in 1815 three Sonatinas for Violin and Piano. -

"Moments Musicaux” and "Impromptus" by Franz Schubert Yoko

"My song implores from the darkest depths" "Moments Musicaux” and "Impromptus" by Franz Schubert Yoko Kaneko (fortepiano Graf, 1827) Although the life of Franz Schubert (1797-1828) was extremely short (31 years), it was perpetually overflowing with music of extraordinary genius. Did he not write more than a thousand works in 18 years, starting in 1810 (with a "Fantasy" for piano four hands) until his death in 1828, his last known work, according to the Deutsch catalogue, being a fugue ... ? It is true that several compositions remained unfinished, while others did not get beyond the preliminary stages, yet so many great works have come down to us perfectly formed. There are nine complete symphonies together with a tenth which has been reconstituted using existing fragments of music; 21 sonatas for piano together with many other piano pieces, including notably, military marches, the C major “Wanderer Fantasy”, the “Valses Sentimentales”, six “Moments Musicaux”, the “Hungarian Melody” “for piano, two books of four “Impromptus”, the “Fantasy" in F minor for piano four hands. The chamber music includes three “sonatinas” for violin and piano, a "Rondo", a “Fantasy" in C major, a Sonata for violin and piano and the “Arpeggione” sonata; fifteen string quartets; six trios either for strings or with piano; two quintets ( the “Trout”, for piano and strings and another for two violins, viola, and two cellos); an “Octet” for strings and winds; 185 chorals; eleven Masses; 15 operas ... and more than two hundred Lieder. The son of a elementary school teacher, expected to become a schoolteacher himself, Franz Schubert's musical gift would soon take over; at the age of 13, he composed a “Fantasy” for piano four hands which is still preserved. -

FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) the Unauthorised Piano Duos, Vol

FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) The Unauthorised Piano Duos, vol. 3 String Quartet in D minor, “Death and the Maiden”, D. 810 38:28 transcribed for piano duet by Robert Franz (1815-1892) (Première recording) ¬ I. Allegro 11:33 • II. Andante con moto 13:15 ® III. Scherzo and Trio: Allegro molto 3:46 ¯ IV. Finale: Presto – Prestissimo 9:54 Symphony in B minor, “Unfinished”, D. 759 and D. 797/1 35:27 complete performing edition (Première recording) ° I. Allegro moderato † 11:11 ± II. Andante con moto † 10:44 ² III Scherzo and Trio: Allegro – Poco meno mosso * 6:32 ³ IV. Finale: Allegro ** 7:00 † transcribed for piano duet by Anselm Hüttenbrenner (1794-1868) * completed and transcribed for piano duet by Anthony Goldstone (b.1944) ** Entr’acte in B minor from Rosamunde, D. 797, transcribed by Friedrich Hermann (1828-1907), and adapted by Anthony Goldstone Total duration: 73:55 GOLDSTONE AND CLEMMOW four hands at one piano FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) THE UNAUTHORISED PIANO DUOS This CD follows Divine Art 25026 and 25039, which also contain first recordings of significant transcriptions for piano duet/duo of Schubert’s masterpieces, including the “Trout” Quintet, the B flat major Piano Trio and the Arpeggione Sonata. It is the result of several years’ detective work, frustrated by frequent blank walls. Thanks are due to Prof. Brian Newbould, who sent me Schubert’s sketches for the scherzo of the symphony and directed me to the location of the unpublished Hüttenbrenner autograph; and to Raymond Brammall, who came to the rescue by using his combined photographic, computer and musical skills to produce large and eminently readable pages from the miniscule film negatives of Anselm’s unclear manuscript. -

Der Tod Und Die Forelle: New Thoughts on Schubert's Quintet

Der Tod und die Forelle: New Thoughts on Schubert's Quintet 1. Michael Griffel Introductory Note: In the early years of Current Musicology, the only required courses beyond the MA level for PhD students in historical musicology were . the two "Research Seminars in Musicology;' one taught by Denis Stevens and the other by Paul Henry Lang. These courses were designed to engage advanced students in original research, advanced methodology, and signifi cant writing and to prepare them for the qualifying examinations on music history and on theoretical and aesthetic writings in the required languages (French, German, Italian, and Latin). In the fall of 1968, Professor Lang selected as his topic for the research seminar (in which I was enrolled) the symphonies of Franz Schubert. This was the last research seminar given by Professor Lang, who was approaching retirement from Columbia. He di vulged to those of us taking the course that in his opinion the three master composers of the tonal era who were most in need of scholarly attention were Handel, Haydn, and Schubert. Lang self-confidently claimed that his recently published study of Handel was setting the record straight on that great composer but that similar work still needed to be done on the other two, and especially on Schubert's instrumental compositions. l The seminar whetted my appetite, and I soon found that Lang was quite right: there was, for example, not a single complete recording of the Schubert symphonies by a major orchestra back in 1968. I decided to write my PhD dissertation on the Schubert symphonies, and so my interest in Schubert's instrumental music got its start. -

(1797-1828) Piano Quintet in a Major, D.667 'Trout' (1819) Allegro Vivace

Programme notes by Chris Darwin. Use freely for non-commercial purposes Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Piano Quintet in A major, D.667 ‘Trout’ (1819) Allegro vivace Andante Scherzo. Presto Tema con variazione. Andantino Finale. Allegro giusto Although written only 7 years after the 'Sonatensatz' trio that we heard before the Interval, the exuberant 'Trout' quintet of 1819 is the work of a master. Together with the 'Quartettsatz' written in 1820 it sets the scene for the great chamber works of his later years: in 1824 the Octet, the A minor “Rosamunde” quartet and the D minor 'Death and the Maiden'; in 1826 the G major quartet; in 1827 his two piano trios; and in his last year, 1828, the incomparable C major two-cello quintet. The 22-year old Schubert's cellist friend Sylvester Paumgartner commissioned the 'Trout' quintet while Schubert was visiting his home town of Steyr in Upper Austria. Paumgartner asked Schubert to include material from his 1817 song 'Die Forelle'. As their mutual friend Albert Stadler, later wrote: '[it was] the particular request of my friend Sylvester Paumgartner, who was quite taken with the delicate little song. The Quintet, according to his wish, was to adopt the structure and instrumentation of Hummel's Quintet, originally Septet, which was then still new.' Paumgartner had invited friends round to play this Hummel quintet, an arrangement, probably by Hummel himself, of the Op 74 Septet of 1816. The Allegro vivace opening flourish of the Trout quintet (illustrated) has a clear resemblance to the triplet arpeggio at the start of the Hummel quintet's Allegro second movement (illustrated). -

Genius Ignited,1811–1819

concert program i: Genius Ignited, 1811–1819 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756–1791) July 18 and 19 String Quartet in d minor, K. 421 (1783) Allegro Saturday, July 18, 6:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Andante MS Arts at Menlo-Atherton Minuetto: Allegretto A Allegretto ma non troppo R Sunday, July 19, 6:00 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School Escher String Quartet: Adam Barnett-Hart, Aaron Boyd, violins; Pierre Lapointe, viola; Brook Speltz, cello G FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797–1828) Program Overview Overture in c minor for String Quartet, D. 8a (1811) On September 28, 1804, at the age of seven, Franz Schubert Escher String Quartet: Adam Barnett-Hart, Aaron Boyd, violins; Pierre Lapointe, viola; Brook Speltz, cello auditioned for Antonio Salieri, the Austrian imperial Kapell- meister and the teacher of Beethoven and Liszt. Coming under Gretchen am Spinnrade, op. 2, D. 118 (Goethe) (October 19, 1814) Joélle Harvey, soprano; Hyeyeon Park, piano ERT PRO ERT the tutelage of one of Europe’s most famous musicians, he C immersed himself in music from all angles: as violinist and Erlkönig, op. 1, D. 328 (Goethe) (1815) violist, singer, composer, and conductor. Concert Program I Nikolay Borchev, baritone; Hyeyeon Park, piano summarizes the amazing first decade of Schubert’s career, dur- ON ing which he composed some seven hundred works. We will INTERMISSION C pay tribute to a major influence, Mozart, with one of his most FRANZ SCHUBERT passionate string quartets, echoed by an early exploration in Die Forelle, op. 32, D. 550 (Schubart) (1817) the same genre by Schubert. -

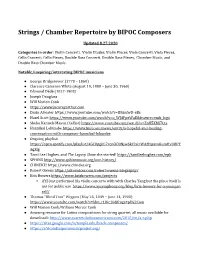

Strings / Chamber Repertoire by BIPOC Composers

Strings / Chamber Repertoire by BIPOC Composers Updated 8.27.2020 Categories in order: Violin Concerti, Violin Etudes, Violin Pieces, Viola Concerti, Viola Pieces, Cello Concerti, Cello Pieces, Double Bass Concerti, Double Bass Pieces, Chamber Music, and Double Bass Chamber Music . Notable/inspiring/interesting BIPOC musicians ● George Bridgetower (1778 – 1860) ● Clarence Cameron White (August 10, 1880 – June 30, 1960) ● Edmund Dédé (1827-1903) ● Joseph Douglass ● Will Marion Cook ● https://www.jecoreyarthur.com ● Darin Atwater https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H8snfwD-eBs ● Hazel Scott https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o_WJ4PpxWaE&feature=emb_logo ● Sheku Kanneh-Mason (Cellist) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZnU5XMl7Cts ● Hannibal Lokumbe https://www.bmi.com/news/entry/a-hopeful-and-healing- conversation-with-composer-hannibal-lokumbe ● Ongoing playlist: https://open.spotify.com/playlist/4GC0pgiFi7renOO0Njw6kF?si=WAB1pavxRumHv0OPY 4qXlg ● Tami Lee Hughes, and The Legacy Show she started! https://tamileehughes.com/epk ● SPHINX http://www.sphinxmusic.org/our-history/ ● CHINEKE! https://www.chineke.org ● Robert Owens https://afrovoices.com/robert-owens-biography/ ● Kris Bowers https://www.krisbowers.com/projects ○ AYS just performed his violin concerto with with Charles Yang but the piece itself is not for public use https://www.aysymphony.org/blog/kris-bowers-for-a-younger- self/ ● Thomas "Blind Tom" Wiggins (May 25, 1849 – June 14, 1908) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ldm_r1Uic10&frags=pl%2Cwn ● Will Marion Cook/William Mercer Cook ● Amazing -

Beyond the Trout Quintet Let It Never Be Said That There Isn’T Enough Chamber Music That Includes the Double Bass by KURT MUROKI

Beyond the Trout Quintet Let it never be said that there isn’t enough chamber music that includes the double bass BY KURT MUROKI Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra principal for 13 players), György Kurtag’s Six Less often heard are gems like the Hindemith bassist Owen Lee maintains that there are Bagatelles, and Vaughan Williams’s Octet, the Lachner Nonet, Lalo’s Deux so many great chamber works out there for Piano Quintet. The list goes on and on.... Aubades, and Mercandante’s Deci mino I, his instrument, that he’d never be able to performed by the Jupiter Symphony Chamber As a New York City-based bassist who play them all. More than sixty compositions Players. Wonderful new works by Mario has been lucky enough to play lots of cham- are written for the “Trout” formation (piano, Davidovsky, John Zorn, and 101-year-old ber music, I must credit three organizations violin, viola, cello, bass) alone, he points out. Elliott Carter are being performed both by for bringing lesser-known ensemble works And, he goes on, the Classical Period itself the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center with bass to my attention: these are the is an “embarrassment of riches”: and other prominent New York contempo- Marlboro Music Festival; the Jupiter Symphony rary music ensembles. ……countless Serenades and Divert Chamber Players, headed by Mei Ying and Yet these are only the tip of the iceberg: imenti by Mozart, to say nothing of his Michael Volpert, who are devoted to inter- The St. Luke’s Chamber Ensemble’s bassist four great String Quintets with bass esting and educational programming and John Feeney—a superb musician and a (Eine Kleine Nachtmusik and the three never repeat the same piece twice; and the friend—recently uncovered a multitude of string divertimenti, K.136, 137, and Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, ensemble works by Domenico Dragonetti 138). -

Download Program Notes (PDF)

PROGRAM: SUNDAYS WITH THE ST. LAWRENCE OCTOBER 4 / 2:30 PM BING CONCERT HALL ARTISTS PROGRAM St. Lawrence String Quartet Joseph Haydn: Quartet in G Minor, op. 20, no. 3 (Hob. III:33) (1772) Geoff Nuttall, violin Allegro con spirito Owen Dalby, violin Menuetto: Allegretto Lesley Robertson, viola Poco adagio Christopher Costanza, cello Allegro di molto Pedja Muzijevic, piano and Graf fortepiano Ralph Vaughan Williams: Piano Quintet in C Minor (1903, rev. 1904–5) Anthony Manzo, double bass Allegro con fuoco Andante Fantasia (quasi variazioni) Sundays with the St. Lawrence is presented in partnership with Music at Stanford. INTERMISSION Franz Schubert: Piano Quintet in A, op. 114, D. 667, Trout (ca. 1819) Allegro vivace Andante Scherzo – Presto Tema con variazioni – Andantino Allegro giusto PROGRAM SUBJECT TO CHANGE. Please be considerate of others and turn off all phones, pagers, and watch alarms, and unwrap all lozenges prior to the performance. Photography and recording of any kind are not permitted. Thank you. 32 STANFORD LIVE MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2015 PROGRAM: SUNDAYS WITH THE ST. LAWRENCE JOSEPH HAYDN (1732–1809) RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS falling chords heard at the very beginning are QUARTET IN G MINOR, OP. 20, (1872–1958) immediately inverted and expanded into a NO. 3 (HOB. III:33) (1772) PIANO QUINTET IN C MINOR flowing melody for viola. Violin and then the (1903, REV. 1904–5) full ensemble develop the idea into a mighty Joseph Haydn wrote his six Op. 20 quartets statement over a sustained pedal note low in in 1772 at the age of 40. They contain his Like his contemporary Edward Elgar, the double bass. -

Notes on the Program by James M

Notes on the Program By James M. Keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter May Chair Quintet for Piano and Strings in A major, D.667, Trout Franz Schubert n the summer of 1819, the 22-year-old Franz Op. 74). Its unusual instrumentation — vio - ISchubert went on a vacation with his close lin, viola, cello, double bass, and piano — ap - friend Johann Michael Vogl to Steyr in Upper parently coincided with the forces provided Austria, a bit southeast of Linz. Vogl, who by his fellow musical aficionados in Steyr. was 29 years Schubert’s elder, had been born Schubert leapt at Paumgartner’s invitation to in the Ennsdorf district of Steyr and since compose a companion piece and was de - 1794 had been a member of the Court Opera lighted to accede to the only stipulation apart in Vienna, where he was one of the com - from the instrumentation: that the new work pany’s star baritones. This distinguished incorporate the melody of Paumgartner’s fa - member of Vienna’s musical establishment vorite Schubert song, “Die Forelle” (“The met the essentially unknown Schubert in Trout”), which had been written two years early 1817, was bowled over by the young earlier. While still on vacation, the composer composer’s talent, and became an important set down some sketches for the resulting interpreter and promoter of his songs. composition, forever known as the Trout The composer would recall the summer of Quintet, and he apparently completed the 1819 as serenely happy, the days filled with piece immediately on his return to Vienna. -

Schubert's ``The Trout'

Schubert’s “The Trout”, Lied to Quintet and back to Lied: a contextual analysis of the pair © Okita, St Ontario To cite this version: © Okita, St Ontario. Schubert’s “The Trout”, Lied to Quintet and back to Lied: a contextual analysis of the pair. Humanities and Social Sciences. Brock University, 2020. English. tel-03005335 HAL Id: tel-03005335 https://hal-hprints.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03005335 Submitted on 14 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. SCHUBRT’S “THE TROUT”: LIED TO QUINTET AND BACK TO LIED A CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF THE PAIR by YOSHIAKI OKITA AN HONORS THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE HUMANITIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE HONORS BATCHELOR OF MUSIC DEGREE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC © YOSHIAKI OKITA BROCK UNIVERSITY ST. CATHARINES ONTARIO April 2020 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopier or other means, Without the permission of the author. ii This thesis has been accepted as conforming to the required standard. _______________________________