The History and Development of Liverpool's Early Public Parks By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAIB Report No 32/2014

ACCIDENT REPORT ACCIDENT sinking oftheDUKW andabandonment amphibiouspassenger VERY SERIOUS MARINE CASUALTY REPORT NO CASUALTY SERIOUS MARINE VERY fire and abandonment of the DUKW amphibious passenger oftheDUKW andabandonment fire amphibiouspassenger Combined report on the investigations ofthe reportCombined ontheinvestigations on the River Thames, London Thames, on theRiver in Salthouse Dock, Liverpool H Wacker Quacker 1 Quacker Wacker on 29 September 2013 on 29September NC on 15June2013 A Cleopatra R and the vehicle vehicle N B IO T A G TI S 32 /2014 DECEMBER 2014 INVE T DEN I C C A NE RI A M Extract from The United Kingdom Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 2012 – Regulation 5: “The sole objective of the investigation of an accident under the Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 2012 shall be the prevention of future accidents through the ascertainment of its causes and circumstances. It shall not be the purpose of an investigation to determine liability nor, except so far as is necessary to achieve its objective, to apportion blame.” NOTE This report is not written with litigation in mind and, pursuant to Regulation 14(14) of the Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 2012, shall be inadmissible in any judicial proceedings whose purpose, or one of whose purposes is to attribute or apportion liability or blame. © Crown copyright, 2014 You may re-use this document/publication (not including departmental or agency logos) free of charge in any format or medium. You must re-use it accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and you must give the title of the source publication. -

“Freedom and Friendship to Ireland”: Ribbonism in Early Nineteenth

"Freedom and Friendship to Ireland": Ribbonism in Early Nineteenth-Century Liverpool* JOHN BELCHEM Summary: The paper examines the role of "nationalist" secret societies among the rapidly growing Irish community in Britain in the 1830s and 1840s. The main port of entry, Liverpool occupied a pivotal role as the two main "Ribbon" societies developed secret networks to provide migrant members with political sanctuary and a range of "tramping" benefits. Through its welfare provision, offered irrespective of skill or trade, Ribbonism engendered a sense of identity wider than that of the familial and regional affiliations through which chain migration typically operated. A proactive influence among immigrant Irish Catholic workers, Ribbonism helped to construct a national or ethnic awareness, initiating the process by which ethnic-sectarian formations came to dominate popular politics in nineteenth-century Liverpool, the nation's second city. This ethnic associational culture was at least as functional, popular and inclusive as the class-based movements and party structures privileged in conventional British historiography. By decoding the ritual, symbolism and violence of secret societies, histo- rians have gained important insights into peasant and community resist- ance to modernization, centralization and change. Given their myriad forms, however, secret societies were not always the preserve of "primitive rebels". In nineteenth-century Ireland, where secret societies were prob- ably most endemic, traditionalist agrarian redresser movements operated alongside urban-based networks which combined labour protection and collective mutuality with forward-looking political and/or nationalist goals.1 There was considerable, often confusing, overlap and fluidity in aims and functions, hence the difficulty in classifying and categorizing Rib- bonism, a new type of secret society which emerged in Ireland around 1811. -

NACS Code Practice Name N82054 Abercromby Health Centre N82086

NACS Code Practice Name N82054 Abercromby Health Centre N82086 Abingdon Family Health Centre N82053 Aintree Park Group Practice N82095 Albion Surgery N82103 Anfield Group Practice N82647 Anfield Health - Primary Care Connect N82094 Belle Vale Health Centre N82067 Benim MC N82671 Bigham Road MC N82078 Bousfield Health Centre N82077 Bousfield Surgery N82117 Brownlow Group Practice N82093 Derby Lane MC N82033 Dingle Park Practice N82003 Dovecot HC N82651 Dr Jude’s Practice Stanley Medical Centre N82646 Drs Hegde and Jude's Practice N82662 Dunstan Village Group Practice N82065 Earle Road Medical Centre N82024 West Derby Medical Centre N82022 Edge Hill MC N82018 Ellergreen Medical Centre N82113 Fairfield General Practice N82676 Fir Tree Medical Centre N82062 Fulwood Green MC N82050 Gateacre Medical Centre N82087 Gillmoss Medical Centre N82009 Grassendale Medical Practice N82669 Great Homer Street Medical Centre N82090 Green Lane MC N82079 Greenbank Rd Surgery N82663 Hornspit MC N82116 Hunts Cross Health Centre N82081 Islington House Surgery N82083 Jubilee Medical Centre N82101 Kirkdale Medical Centre N82633 Knotty Ash MC N82014 Lance Lane N82019 Langbank Medical Centre N82110 Long Lane Medical Centre N82001 Margaret Thompson M C N82099 Mere Lane Practice N82655 Moss Way Surgery N82041 Oak Vale Medical Centre N82074 Old Swan HC N82026 Penny Lane Surgery N82089 Picton Green N82648 Poulter Road Medical Centre N82011 Priory Medical Centre N82107 Queens Drive Surgery N82091 GP Practice Riverside N82058 Rock Court Surgery N82664 Rocky Lane Medical -

Coach Welcome Scheme

Coach welcome scheme LIVERPOOL COACH WELCOME There is secure coach parking at the Eco Coach groups can register for a special Visitor Centre alongside the park and ride Coach Welcome, which involves a personal scheme. This includes lounge, kitchen welcome to the city of Liverpool from one and shower facilities for drivers. of our enthusiastic coach hosts, the latest For more information visit www.visitsouthport.com information on what’s on, complimentary or contact Steve Christian on +44 (0)151 934 2319 maps, rest room and refreshment facilities. For drivers, there are coach drop-off WIRRAL COACH WELCOME and pick-up facilities, parking and traffic For a Mersey Ferries river cruise, park at information and refreshments. Woodside Ferry Terminal. Mersey Ferries links There are two locations: Liverpool Cathedral a number of exciting waterfront attractions in the city’s historic Hope Street Quarter, in Liverpool and Wirral, enabling you to and at Liverpool ONE bus station. create flexible days out for your group. We recommend booking at least 10 days in advance. Port Sunlight, a fascinating 19th century garden • LIVERPOOL CATHEDRAL village, is a very popular group travel destination +44 (0)151 702 7284 and home to both the Port Sunlight Museum and [email protected] Lady Lever Art Gallery. There is extensive free coach parking adjacent to the Lady Lever Art Gallery, with • LIVERPOOL ONE BUS STATION the village attractions easily accessible on foot. +44 (0)151 330 1354 [email protected] For more information about these and more visit www.visitwirral.com/visitor-info/group-travel SOUTHPORT COACH WELCOME Coach hosts are available from April to October to meet and greet coach visitors disembarking at the coach drop-off point on Lord Street, adjacent to The Atkinson. -

Student Guide to Living in Liverpool

A STUDENT GUIDE TO LIVING IN LIVERPOOL www.hope.ac.uk 1 LIVERPOOL HOPE UNIVERSITY A STUDENT GUIDE TO LIVING IN LIVERPOOL CONTENTS THIS IS LIVERPOOL ........................................................ 4 LOCATION ....................................................................... 6 IN THE CITY .................................................................... 9 LIVERPOOL IN NUMBERS .............................................. 10 DID YOU KNOW? ............................................................. 11 OUR STUDENTS ............................................................. 12 HOW TO LIVE IN LIVERPOOL ......................................... 14 CULTURE ....................................................................... 17 FREE STUFF TO DO ........................................................ 20 FUN STUFF TO DO ......................................................... 23 NIGHTLIFE ..................................................................... 26 INDEPENDENT LIVERPOOL ......................................... 29 PLACES TO EAT .............................................................. 35 MUSIC IN LIVERPOOL .................................................... 40 PLACES TO SHOP ........................................................... 45 SPORT IN LIVERPOOL .................................................... 50 “LIFE GOES ON SPORT AT HOPE ............................................................. 52 DAY AFTER DAY...” LIVING ON CAMPUS ....................................................... 55 CONTACT -

Liverpool City Region Visitor Economy Strategy to 2020

LiverpooL City region visitor eConomy strategy to 2020 oCtober 2009 Figures updated February 2011 The independent economic model used for estimating the impact of the visitor economy changed in 2009 due to better information derived about Northwest day visitor spend and numbers. All figures used in this version of the report have been recalibrated to the new 2009 baseline. Other statistics have been updated where available. Minor adjustments to forecasts based on latest economic trends have also been included. All other information is unchanged. VisiON: A suMMAry it is 2020 and the visitor economy is now central World Heritage site, and for its festival spirit. to the regeneration of the Liverpool City region. it is particularly famous for its great sporting the visitor economy supports 55,000 jobs and music events and has a reputation for (up from 41,000 in 2009) and an annual visitor being a stylish and vibrant 24 hour city; popular spend of £4.2 billion (up from £2.8 billion). with couples and singles of all ages. good food, shopping and public transport underpin Liverpool is now well established as one of that offer and the City region is famous for its europe’s top twenty favourite cities to visit (39th friendliness, visitor welcome, its care for the in 2008). What’s more, following the success of environment and its distinctive visitor quarters, its year as european Capital of Culture, the city built around cultural hubs. visitors travel out continued to invest in its culture and heritage to attractions and destinations in other parts of and destination marketing; its decision to use the City region and this has extended the length the visitor economy as a vehicle to address of the short break and therefore increased the wider economic and social issues has paid value and reach of tourism in the City region. -

4 4A Liverpool

Valid from 19 January 2020 Bus timetable Liverpool ONE- 4 4A Dingle/Sefton Park circulars These services are provided by Merseytravel LIVERPOOL CITY CENTRE Liverpool ONE Bus Station Kings Parade DINGLE Park Hill Road TOXTETH Croxteth Road (4) SEFTON PARK Greenbank Lane MOSSLEY HILL HOSPITAL Ullet Road DINGLE Park Hill Road Kings Parade LIVERPOOL CITY CENTRE Liverpool ONE Bus Station www.merseytravel.gov.uk What’s changed? Times are changed on Route 4. The 0900 Route 4 journey from Liverpool One Bus Station is rerouted and renumbered as route 4A, the times are subsequently changed. The Route 4A journey departing Liverpool One at 1500 is retimed along the route. All other 4A journeys remain unaltered. Any comments about this service? If you’ve got any comments or suggestions about the services shown in this timetable, please contact the bus company who runs the service: Peoplesbus Customer Service Centre, PO Box 57, Liverpool, Merseyside, L9 8YX 0151 523 4010 Contact us at Merseytravel: By e-mail [email protected] By phone 0151 330 1000 In writing PO Box 1976, Liverpool, L69 3HN Need some help or more information? For help planning your journey, call us between 0800 - 2000, 7 days a week on 0151 330 1000 You can visit one of our Travel Centres across the Merseytravel network to get information about all public transport services. To find out opening times, phone us on 0151 330 1000. Our website contains lots of information about public transport across Merseyside. You can visit our website at www.merseytravel.gov.uk Bus services may run to different timetables during bank and public holidays, so please check your travel plans in advance. -

The Medieval English Borough

THE MEDIEVAL ENGLISH BOROUGH STUDIES ON ITS ORIGINS AND CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY BY JAMES TAIT, D.LITT., LITT.D., F.B.A. Honorary Professor of the University MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS 0 1936 MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS Published by the University of Manchester at THEUNIVERSITY PRESS 3 16-324 Oxford Road, Manchester 13 PREFACE its sub-title indicates, this book makes no claim to be the long overdue history of the English borough in the Middle Ages. Just over a hundred years ago Mr. Serjeant Mere- wether and Mr. Stephens had The History of the Boroughs Municipal Corporations of the United Kingdom, in three volumes, ready to celebrate the sweeping away of the medieval system by the Municipal Corporation Act of 1835. It was hardly to be expected, however, that this feat of bookmaking, good as it was for its time, would prove definitive. It may seem more surprising that the centenary of that great change finds the gap still unfilled. For half a century Merewether and Stephens' work, sharing, as it did, the current exaggera- tion of early "democracy" in England, stood in the way. Such revision as was attempted followed a false trail and it was not until, in the last decade or so of the century, the researches of Gross, Maitland, Mary Bateson and others threw a fiood of new light upon early urban development in this country, that a fair prospect of a more adequate history of the English borough came in sight. Unfortunately, these hopes were indefinitely deferred by the early death of nearly all the leaders in these investigations. -

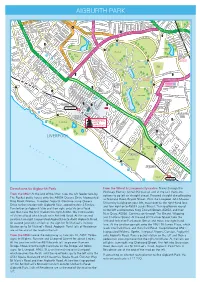

Aigburth Park

G R N G A A O A T D B N D LM G R R AIGBURTHA PARK 5 P R I R M B T 5 R LTAR E IN D D GR G 6 R 1 I Y CO O Superstore R R O 5 V Y 7 N D 2 R S E 5 E E L T A C L 4 A Toxteth Park R E 0 B E P A E D O Wavertree H S 7 A T A L S 8 Cemetery M N F R O Y T A Y E A S RM 1 R N Playground M R S P JE N D K V 9 G E L A IC R R K E D 5 OV N K R R O RW ST M L IN E O L A E O B O A O P 5 V O W IN A U C OL AD T R D A R D D O E A S S 6 P N U E Y R U B G U E E V D V W O TL G EN T 7 G D S EN A V M N N R D 1 7 I B UND A A N E 1 N L A 5 F R S V E B G G I N L L S E R D M A I T R O N I V V S R T W N A T A M K ST E E T V P V N A C Y K V L I V A T A D S R G K W I H A D H K A K H R T C N F I A R W IC ID I A P A H N N R N L L E A E R AV T D E N W S S L N ARDE D A T W D T N E A G K A Y GREENH H A H R E S D E B T B E M D T G E L M O R R Y O T V I N H O O O A D S S I T L M L R E T A W V O R K E T H W A T C P U S S R U Y P IT S T Y D C A N N R I O C H R C R R N X N R RL T E TE C N A DO T E E N TH M 9 A 56 G E C M O U 8 ND R S R R N 0 2 A S O 5 R B L E T T D R X A A L O R BE E S A R P M R Y T Y L A A C U T B D H H S M K RT ST S E T R O L E K I A H N L R W T T H D A L RD B B N I W A LA 5175 A U W I R T Y P S R R I F H EI S M S O Y C O L L T LA A O D O H A T T RD K R R H T O G D E N D L S S I R E DRI U V T Y R E H VE G D A ER E H N T ET A G L Y R EFTO XT R E V L H S I S N DR R H D E S G S O E T T W T H CR E S W A HR D R D Y T E N V O D U S A O M V B E N I O I IR R S N A RIDG N R B S A S N AL S T O T L D K S T R T S V T O R E T R E O A R EET E D TR K A D S LE T T E P E TI S N -

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project December 2011 Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project Museum of Liverpool Pier Head Liverpool L3 1DG © Trustees of National Museums Liverpool and English Heritage 2011 Contents Introduction to Historic Settlement Study..................................................................1 Aigburth....................................................................................................................4 Allerton.....................................................................................................................7 Anfield.................................................................................................................... 10 Broadgreen ............................................................................................................ 12 Childwall................................................................................................................. 14 Clubmoor ............................................................................................................... 16 Croxteth Park ......................................................................................................... 18 Dovecot.................................................................................................................. 20 Everton................................................................................................................... 22 Fairfield ................................................................................................................. -

A Vision for North Shore

View from Lee - north to south Published September 2020 3 North Shore Vision I am pleased to introduce this North Shore Vision for the Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City World Heritage Site. Foreword Liverpool is a city that is undergoing a multi-billion pound renaissance and we are constantly seeking the right balance where regeneration and conservation can complement each other. We are proud of our unique heritage and have a desire to ensure that the city continues to thrive, with its historic legacy safeguarded and enhanced. On 17 July 2019, Liverpool City Council declared a Climate Change Emergency and I led a debate on the impending global ecological disaster, calling on all political parties to come together to rise to the challenge of making Liverpool a net zero carbon city by 2030. The way we do things in the future will need to change to a more sustainable model. To achieve this, the city has embraced the principles of the United Nations Development and this document sets out our ambitions for future growth and development for the North Shore area of the city firmly within this context. We have already begun work with partners to deliver that ambition. Existing and highly successful examples include the iconic Titanic Hotel redevelopment, restoration of the Tobacco Warehouse and the proposed refurbishment of the listed Engine House at Bramley Moore Dock which reinvigorate dilapidated heritage assets on the North Docks, providing access and interpretation to a new generation of people in the City. Liverpool has a well-earned reputation for being a city of firsts. -

Reconstructing Public Housing Liverpool’S Hidden History of Collective Alternatives

Reconstructing Public Housing Liverpool’s hidden history of collective alternatives Reconstructing Public Housing Liverpool’s hidden history of collective alternatives Reconstructing Public Housing Matthew Thompson LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS First published 2020 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2020 Matthew Thompson The right of Matthew Thompson to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A British Library CIP record is available ISBN 978-1-78962-108-2 paperback eISBN 978-1-78962-740-4 Typeset by Carnegie Book Production, Lancaster An Open Access edition of this book is available on the Liverpool University Press website and the OAPEN library. Contents Contents List of Figures ix List of Abbreviations x Acknowledgements xi Prologue xv Part I Introduction 1 Introducing Collective Housing Alternatives 3 Why Collective Housing Alternatives? 9 Articulating Our Housing Commons 14 Bringing the State Back In 21 2 Why Liverpool of All Places? 27 A City of Radicals and Reformists 29 A City on (the) Edge? 34 A City Playing the Urban Regeneration Game 36 Structure of the Book 39 Part II The Housing Question 3 Revisiting