Angry Judges Terry A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notre Dame Lawyer—2018 Notre Dame Law School

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Notre Dame Lawyer Law School Publications 2018 Notre Dame Lawyer—2018 Notre Dame Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/nd_lawyer Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Notre Dame Law School, "Notre Dame Lawyer—2018" (2018). Notre Dame Lawyer. 39. https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/nd_lawyer/39 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Lawyer by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Q&A with Dean Newton Pg. 2 Big Ideas The expansion of ND Law’s intellectual property program is bearing fruit Pg. 20 20 18 A DIFFERENT KIND of LAWYER PHOTOGRAPHY Alicia Sachau and University Marketing Communications EDITOR Kevin Allen Notre Dame Lawyer 1337 Biolchini Hall Notre Dame, IN 46556 574-631-5962 [email protected] Inside 2 Dean Newton 4 Briefs & News 10 Profiles: A Different Kind of Lawyer 16 London Law at 50 20 Intellectual Property 26 Father Mike 30 Faculty News 36 Alumni Notes 44 In Memoriam 46 The Couples of ’81 48 Interrogatory Briefs Dean Newton Steps Down Joseph A. Matson Dean and Professor of Law Nell Jessup Newton will conclude her tenure as dean of Notre Dame Law School on June 30, 2019, after 10 years of service. What was your rela- ÅZ[\\QUMIVLM^MVUMM\QVO sion that leads to follow-up tionship with Notre Dame Fr. Ted. These memories MUIQT[)_ITSIZW]VL\PM before you became the Law are even more tender TISM[WZ\W\PM/ZW\\WKIV School’s dean? because Rob died in 1995 provide a moment to be My brother Rob Mier of lymphoma caused by his grateful for all the ways that attended ND on a Navy exposure to Agent Orange the Notre Dame community ROTC scholarship. -

International Sales Autumn 2017 Tv Shows

INTERNATIONAL SALES AUTUMN 2017 TV SHOWS DOCS FEATURE FILMS THINK GLOBAL, LIVE ITALIAN KIDS&TEEN David Bogi Head of International Distribution Alessandra Sottile Margherita Zocaro Cristina Cavaliere Lucetta Lanfranchi Federica Pazzano FORMATS Marketing and Business Development [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Mob. +39 3351332189 Mob. +39 3357557907 Mob. +39 3334481036 Mob. +39 3386910519 Mob. +39 3356049456 INDEX INDEX ... And It’s Snowing Outside! 108 As My Father 178 Of Marina Abramovic 157 100 Metres From Paradise 114 As White As Milk, As Red As Blood 94 Border 86 Adriano Olivetti And The Letter 22 46 Assault (The) 66 Borsellino, The 57 Days 68 A Case of Conscience 25 At War for Love 75 Boss In The Kitchen (A) 112 A Good Season 23 Away From Me 111 Boundary (The) 50 Alex&Co 195 Back Home 12 Boyfriend For My Wife (A) 107 Alive Or Preferably Dead 129 Balancing Act (The) 95 Bright Flight 101 All The Girls Want Him 86 Balia 126 Broken Years: The Chief Inspector (The) 47 All The Music Of The Heart 31 Bandit’s Master (The) 53 Broken Years: The Engineer (The) 48 Allonsanfan 134 Bar Sport 118 Broken Years: The Magistrate (The) 48 American Girl 42 Bastards Of Pizzofalcone (The) 15 Bruno And Gina 168 Andrea Camilleri: The Wild Maestro 157 Bawdy Houses 175 Bulletproof Heart (A) 1, 2 18 Angel of Sarajevo (The) 44 Beachcombers 30 Bullying Lesson 176 Anija 173 Beauty And The Beast (The) 54 Call For A Clue 187 Anna 82 Big Racket (The) -

The Religious Affiliations of Trump's Judicial Nominees

The Religious Affiliations of Trump's Judicial Nominees U.S. Supreme Court Religion Federalist Society Member Neil Gorsuch Catholic/Episcopal Listed on his SJQ U.S. Court of Appeals Amul Thapar Catholic Former John K. Bush Episcopal Yes Kevin Newsom Yes Amy Coney Barrett Catholic Yes Joan Larsen Former David Stras Jewish Yes Allison H. Eid Yes Ralph R. Erickson Catholic Stephanos Bibas Eastern Orthodox Yes Michael B. Brennan Yes L. Steven Grasz Presbyterian (PCA) Yes Ryan Wesley Bounds Yes Elizabeth L. Branch Yes Stuart Kyle Duncan Catholic Yes Gregory G. Katsas Yes Don R. Willett Baptist James C. Ho U.S. District Courts David Nye Mormon Timothy J. Kelly Catholic Yes Scott L. Palk Trevor N. McFadden Anglican Yes Dabney L. Friedrich Episcopal Claria Horn Boom Michael Lawrence Brown William L. Campbell Jr. Presbyterian Thomas Farr Yes Charles Barnes Goodwin Methodist Mark Norris Episcopal Tommy Parker Episcopal William McCrary Ray II Baptist Eli J. Richardson Tripp Self Baptist Yes Annemarie Carney Axon Liles C. Burke Methodist Donald C Coggins Jr. Methodist Terry A. Doughty Baptist Michael J. Juneau Christian A. Marvin Quattlebaum Jr. Presbyterian Holly Lou Teeter Catholic Robert E. Wier Methodist R. Stan Baker Methodist Jeffrey Uhlman Beaverstock Methodist John W. Broomes Baptist Walter David Counts III Baptist Rebecca Grady Jennings Methodist Matthew J. Kacsmaryk Christian Yes, in college Emily Coody Marks Yes Jeffrey C. Mateer Christian Terry F. Moorer Christian Matthew S. Petersen Former Fernando Rodriguez Jr. Christian Karen Gren Scholer Brett Joseph Talley Christian Howard C Nielson, Jr. Daniel Desmond Domenico Barry W. Ashe Kurt D. -

Trump Judges: Even More Extreme Than Reagan and Bush Judges

Trump Judges: Even More Extreme Than Reagan and Bush Judges September 3, 2020 Executive Summary In June, President Donald Trump pledged to release a new short list of potential Supreme Court nominees by September 1, 2020, for his consideration should he be reelected in November. While Trump has not yet released such a list, it likely would include several people he has already picked for powerful lifetime seats on the federal courts of appeals. Trump appointees' records raise alarms about the extremism they would bring to the highest court in the United States – and the people he would put on the appellate bench if he is reelected to a second term. According to People For the American Way’s ongoing research, these judges (including those likely to be on Trump’s short list), have written or joined more than 100 opinions or dissents as of August 31 that are so far to the right that in nearly one out of every four cases we have reviewed, other Republican-appointed judges, including those on Trump’s previous Supreme Court short lists, have disagreed with them.1 Considering that every Republican president since Ronald Reagan has made a considerable effort to pick very conservative judges, the likelihood that Trump could elevate even more of his extreme judicial picks raises serious concerns. On issues including reproductive rights, voting rights, police violence, gun safety, consumer rights against corporations, and the environment, Trump judges have consistently sided with right-wing special interests over the American people – even measured against other Republican-appointed judges. Many of these cases concern majority rulings issued or joined by Trump judges. -

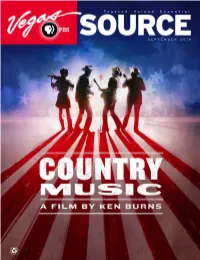

Vegas PBS Source, Volume No

Trusted. Valued. Essential. SEPTEMBER 2019 Vegas PBS A Message from the Management Team General Manager General Manager Tom Axtell, Vegas PBS Educational Media Services Director Niki Bates Production Services Director Kareem Hatcher Business Manager Brandon Merrill Communications and Brand Management Director Allison Monette Content Director Explore a True American Cyndy Robbins Workforce Training & Economic Development Director Art Form in Country Music Debra Solt Interim Director of Development and Strategic Relations en Burns is television’s most prolific documentarian, and PBS is the Clark Dumont exclusive home he has chosen for his work. Member donations make it Engineering, IT and Emergency Response Director possible for us to devote enough research and broadcast time to explore John Turner the facts, nuances and impact of history in our daily lives and our shared SOUTHERN NEVADA PUBLIC TELEVISION BOARD OF DIRECTORS American values. Since his first film in 1981, Ken Burns has been telling Executive Director Kunique and fascinating stories of the United States. Tom Axtell, Vegas PBS Ken has provided historical insights on events like The Civil War, Prohibition and President The Vietnam War. He has investigated the impact of important personalities in The Tom Warden, The Howard Hughes Corporation Roosevelts, Thomas Jefferson and Mark Twain, and signature legacies like The Vice President Brooklyn Bridge,The National Parks and The Statute of Liberty. Now the filmmaker Clark Dumont, Dumont Communications, LLC explores another thread of the American identity in Country Music. Beginning Sunday, Secretary September 15 at 8 p.m., step back in time and explore the remarkable stories of the Nora Luna, UNR Cooperative Extension people and places behind this true American art form in eight two-hour segments. -

Byronecho2136.Pdf

THE BYRON SHIRE ECHO Advertising & news enquiries: Mullumbimby 02 6684 1777 Byron Bay 02 6685 5222 seven Fax 02 6684 1719 [email protected] [email protected] http://www.echo.net.au VOLUME 21 #36 TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 2007 echo entertainment 22,300 copies every week Page 21 $1 at newsagents only YEAR OF THE FLYING PIG Fishheads team wants more time at Brothel approval Byron Bay swimming pool goes to court Michael McDonald seeking a declaration the always intended ‘to hold Rick and Gayle Hultgren, development consent was activities involving children’ owners of the Byron Enter- null and void. rather than as for car parking tainment Centre, are taking Mrs Hultgren said during as mentioned in the staff a class 4 action in the Land public access at Council’s report. and Environment Court meeting last Thursday that ‘Over 1,000 people have against Byron Shire Coun- councillors had not been expressed their serious con- cil’s approval of a brothel aware of all the issues cern in writing. Our back near their property in the involved when considering door is 64 metres away from Byron Arts & Industry the brothel development the brothel in a direct line of Estate. An initial court hear- application (DA). She said sight. Perhaps 200 metres ing was scheduled for last their vacant lot across the would be better [as a Council Friday, with the Hultgrens street from the brothel was continued on page 2 Fishheads proprietors Mark Sims and Ralph Mamone at the pool. Photo Jeff Dawson Paragliders off to world titles Michael McDonald dispute came to prominence requirement for capital The lessees of the Byron Bay again with Cr Bob Tardif works. -

Senator Chuck Grassley and Judicial Confirmations

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2019 Senator Chuck Grassley and Judicial Confirmations Carl Tobias University of Richmond - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Courts Commons, and the Judges Commons Recommended Citation Carl Tobias, Senator Chuck Grassley and Judicial Confirmations, 104 Iowa L. Rev. Online 31 (2019). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CARL_PDF PROOF FINAL 12.1.2019 FONT FIX (DO NOT DELETE) 12/4/2019 2:15 PM Senator Chuck Grassley and Judicial Confirmations Carl Tobias* I. 2015–16 PROCESSES ....................................................................... 33 A. THE 2015–16 DISTRICT COURT PROCESSES ............................... 34 1. The Nomination Process ................................................ 34 2. The Confirmation Process .............................................. 36 i. Committee Hearings ..................................................... 36 ii. Committee Votes ........................................................... 37 iii. Floor Votes ................................................................... 38 B. THE 2015–16 APPELLATE COURT PROCESSES ........................... -

Senato Della Repubblica Relazione

SENATO DELLA REPUBBLICA XVII LEGISLATURA Doc. CLVII n. 4 RELAZIONE SULL'ATTIVITÀ SVOLTA E SUI PROGRAMMI DI LAVORO DELL'AUTORITÀ PER LE GARANZIE NELLE COMUNICAZIONI (Aggiornata al 30 aprile 2016) (Articolo 1, comma 6, lettera c), n. 12), della legge 31 luglio 1997, n. 249) Presentata dal Ministro per le riforme costituzionali e i rapporti con il Parlamento (BOSCHI) Comunicata alla Presidenza il 1° luglio 2016 Relazione annuale 2016 sull’attività svolta e sui programmi di lavoro www.agcom.it www.agcom.it RELAZIONE ANNUALE 2016 sull’attività svolta e sui programmi di lavoro Autorità per le garanzie nelle comunicazioni Presidente ANGELO MARCELLO CARDANI Componenti ANTONIO MARTUSCIELLO ANTONIO NICITA FRANCESCO POSTERARO ANTONIO PRETO Segretario generale RICCARDO CAPECCHI Vice segretari generali LAURA ARÌA ANTONIO PERRUCCI Capo di gabinetto del Presidente ANNALISA D’ORAZIO Indice Prefazione del Presidente . 7 CAPITOLO I CAPITOLO III L’operato dell’Autorità nel periodo 2015-2016 I risultati raggiunti, le strategie per il nelle principali aree di interesse . 9 prossimo anno e le attività programmatiche 119 1.1 Le attività regolamentari e di vigilanza nei 3.1 Le attività svolte in attuazione degli obiettivi mercati delle telecomunicazioni . 12 strategici pianificati . 122 1.2 I servizi “media”: analisi, regole e controlli . 18 3.2 I risultati del piano di monitoraggio . 134 1.3 Tutela e garanzia dei diritti nel sistema digitale . 22 3.3 Le priorità strategiche di intervento per il prossimo anno . 153 1.4 La regolamentazione e la vigilanza nel settore postale . 32 1.5 I rapporti con i consumatori e gli utenti . 35 1.6 La nuova generazione regolamentare: spettro radio per telecomunicazioni e servizi digitali 45 CAPITOLO IV 1.7 L’attività ispettiva ed il Registro degli operatori L’organizzazione dell’Autorità e le relazioni di comunicazione . -

Federal Judiciary Tracker

Federal Judiciary Tracker An up-to-date look at the federal judiciary and the status of President Trump’s judicial nominations October 23, 2020 Trump has had 225 federal judges confirmed while 25 seats remain vacant without a nominee Status of key positions 25 President Trump inherited 108 federal requiring Senate 41 judge vacancies confirmation As of October 22, 2020: ■ No nominee ■ Awaiting confirmation 157 judiciary positions have opened up ■ Confirmed during Trump’s presidency and either remain vacant or have been filled Total: 265 potential Trump nominations 225 Source: United States Courts Trump has had more circuit judges confirmed than the average of recent presidents at this point Number of Federal Judges Nominated and Confirmed Trump 161 53 2 ■ District court judge ■ Circuit court judge ■ Supreme Court judge Obama 128 30 2 Source: Federal Judicial Center Bush 165 35 Clinton 169 30 2 HW Bush 148 42 2 In three and a half years, Trump has confirmed a higher number of circuit judges as prior presidents in four years Number of Federal Judges Nominated and Confirmed Trump 161 53 2 ■ District court judge ■ Circuit court judge Obama 141 30 2 ■ Supreme Court judge Source: Federal Judicial Center Bush 168 35 Clinton 169 30 2 HW Bush 148 42 2 An overview of the Article III courts US District Courts US Court of Appeals Supreme Court Organization: Organization: Organization: • The nation is split into 94 • Federal judicial districts • The Supreme Court is the federal judicial districts are organized into 12 highest court in the US • The District of Columbia circuits, which each have a • There are nine justices on and four US territories court of appeals. -

Cc July 06.Qxp

“where a good crime C r i m e can be had by all” c h r o n i c l e Issue #246 july 2006 BOOKS & DVDS A number of books have TV series adapted from them. Here is a selection from our shelves: ANDREA CAMILLERI Inspector Salvo Montalbano is the fictional creation of Sicilian writer Andrea Camilleri. Montalbano’s character and manner encapsulate much of Sicilian mythology – brooding philosophy, whip-smart dialogue, rugged beauty, superb food and of course astute detective work! I can heartily recommend both the books and the TV series (in Italian with English subtitles, and starring Luca Zingaretti): Books The Shape of Water, The Snack Thief, The Terracotta Dog, The Voice of the Violin (all Pb 19.95), Excursion to Tindari (Tp 30.00) and The Smell of the Night (Pb 27.00). DVDs Volume 1: Terracotta Dog, Shape of Water, Snack Thief, Voice of the Violin and Artist’s Touch (3-DVD set 49.95) Volume 2: A Trip to Tindari, The Sense of Touch, Montalbano’s Croquettes, The Scent of the Night and The Goldfinch and the Cat (3-DVD set 49.95) CAROLINE GRAHAM Nothing is what it seems behind the well-trimmed hedges of the picturesque cottages in the idyllic English countryside of Midsomer, as Inspector Barnaby and Sergeant Troy soon discover. John Nettles stars as Inspector Barnaby and again I can recommend both the books and the TV series. Books Death of a Hollow Man, Death in Disguise, Faithful Unto Death, A Ghost in the Machine, The Killings at Badger’s Drift, A Place of Safety and Written in Blood (all Pb 18.95). -

Cc Feb 09.Qxp

“where a good crime C r i m e can be had by all” c h r o n i c l e Issue #277 February 2009 DVDs We have quite a collection of crime DVDs – both movies and TV series. Some of the TV series I seem to have missed on free-to-air TV (or maybe they never made it). Anyway here are some of the TV series now available on DVD to whet your appetite: Wycliffe, based on the novels by W J Burley and starring Jack Shepherd as the meticulous and clever Detective Superintendent Charles Wycliffe. Series 1 (2 DVDs) $35, Series 2 (2 DVDs) $35, Series 3 (2 DVDs) $35, Series 4 (3 DVDs) $40 Cadfael: The Complete Series, based on the novels by Ellis Peters and starring Derek Jacobi as Brother Cadfael. 8 DVDs $80 Wallander, based on the novels by Henning Mankell and starring Krister Henriksson as Kurt Wallander. Swedish with English subtitles. Volume 1 (3 DVDs with 6 episodes) $51.95, Volume 2 (4 DVDs with 7 episodes) $50.95 Hetty Wainthropp Investigates starring Patricia Routledge as the redoubtable Hetty. Complete 2nd Series (2 DVDs) $39.95, Complete 3rd Series (3 DVDs) $49.95 Cracker: The Ultimate Collection, starring Robbie Coltrane and written by Jimmy McGovern. Complete series 1, 2 & 3, plus 2 movie-length specials (9 DVDs) $80 Danger Man: The Complete 1964-66 Series, starring Patrick McGoohan as John Drake. All 47 x 50-minute Danger Man adventures remastered, complete and uncut, with guest stars including Paul Eddington, Susan Hampshire, Warren Mitchell, Peter Bowles and Sylvia Sims. -

Biden Administration and 117Th Congress

Updated January 15, 2021 1 Executive office of the President (EOP) The Executive Office of the President (EOP) comprises the offices and agencies that support the work of the president at the center of the executive branch of the United States federal government. To provide the President with the support that he or she needs to govern effectively, the Executive Office of the President (EOP) was created in 1939 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The EOP has responsibility for tasks ranging from communicating the President’s message to the American people to promoting our trade interests abroad. The EOP is also referred to as a 'permanent government', with many policy programs, and the people who implement them, continuing between presidential administrations. This is because there is a need for qualified, knowledgeable civil servants in each office or agency to inform new politicians. With the increase in technological and global advancement, the size of the White House staff has increased to include an array of policy experts to effectively address various fields. There are about 4,000 positions in the EOP, most of which do not require confirmation from the U.S. Senate. Senior staff within the Executive Office of the President have the title Assistant to the President, second-level staff have the title Deputy Assistant to the President, and third-level staff have the title Special Assistant to the President. The core White House staff appointments, and most Executive Office officials generally, are not required to be confirmed by the U.S. Senate, although there are a handful of exceptions (e.g., the Director of the Office of Management and Budget, the Chair and members of the Council of Economic Advisers, and the United States Trade Representative).