The Stratigraphy and Structure of the Moine Rocks N of the Schiehallion Complex, Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal 60 Spring 2016

JOHN MUIR TRUST 10 The push for stronger regulation of deer management in Scotland 16 How campaigning contributes to JOURNAL the Trust’s long-term vision 25 What John Muir Award activity 60 SPRING 2016 means for the UK’s wild places Living mountain Schiehallion through the seasons CONTENTS 033 REGULARS 05 Chief executive’s welcome 06 News round-up 09 Wild moments In this new section, members share their stories and poems about experiences in wild places 28 32 Books The Rainforests of Britain and Ireland - a Traveller’s Guide, Clifton Bain 22 34 Interview Kevin Lelland caught up with Doug Allan, the celebrated wildlife film-maker best known for his work filming life in inhospitable places for series such as the BBC’s Blue Planet and Frozen Planet FEATURES 10 A time of change Mike Daniels outlines why the Trust continues to push for stronger regulation of deer management in Scotland 16 Pursuing a vision Mel Nicoll highlights how our campaign work – and the invaluable support of members – contributes to the Trust’s long-term vision for 25 wild places 19 Value and protect In this extract from a recent keynote address, Stuart Brooks explains his vision for reconnecting people and nature 20 A lasting impact Adam Pinder highlights the importance to the Trust of gifts in wills, and the impact of one particular gift on our property at Glenlude in 34 the Scottish Borders PHOTOGRAPHY (CLOCKWISE FROM TOP): JESSE HARRISON; LIZ AUTY; JOHN MUIR AWARD; DOUG ALLAN 22 A year on the fairy hill Liz Auty provides an insight into her work COVER: PURPLE SAXIFRAGE, -

Protected Landscapes: the United Kingdom Experience

.,•* \?/>i The United Kingdom Expenence Department of the COUNTRYSIDE COMMISSION COMMISSION ENVIRONMENT FOR SCOTLAND NofChern ireianc •'; <- *. '•ri U M.r. , '^M :a'- ;i^'vV r*^- ^=^l\i \6-^S PROTECTED LANDSCAPES The United Kingdom Experience Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from UNEP-WCIVIC, Cambridge http://www.archive.org/details/protectedlandsca87poor PROTECTED LANDSCAPES The United Kingdom Experience Prepared by Duncan and Judy Poore for the Countryside Commission Countryside Commission for Scotland Department of the Environment for Northern Ireland and the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Published for the International Symposium on Protected Landscapes Lake District, United Kingdom 5-10 October 1987 * Published in 1987 as a contribution to ^^ \ the European Year of the Environment * W^O * and the Council of Europe's Campaign for the Countryside by Countryside Commission, Countryside Commission for Scotland, Department of the Environment for Northern Ireland and the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources © 1987 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Avenue du Mont-Blanc, CH-1196 Gland, Switzerland Additional copies available from: Countryside Commission Publications Despatch Department 19/23 Albert Road Manchester M19 2EQ, UK Price: £6.50 This publication is a companion volume to Protected Landscapes: Experience around the World to be published by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, -

![Landscape ? 2 +%, 7C E ?K\A]` (- 2.2 Why Is Landscape Important to Us? 2 +%- Ad\Z 7C E \E^ 7C E 1Cdfe^ )& 2.3 Local Landscape Areas (Llas) 3 +%](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1205/landscape-2-7c-e-k-a-2-2-why-is-landscape-important-to-us-2-ad-z-7c-e-e-7c-e-1cdfe-2-3-local-landscape-areas-llas-3-2451205.webp)

Landscape ? 2 +%, 7C E ?K\A]` (- 2.2 Why Is Landscape Important to Us? 2 +%- Ad\Z 7C E \E^ 7C E 1Cdfe^ )& 2.3 Local Landscape Areas (Llas) 3 +%

Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 +%* Ajh\j` B\n (' 2 BACKGROUND 2 +%+ 2_e Dh\]ba_ (* 2.1 What is landscape ? 2 +%, 7c_e ?k\a]` (- 2.2 Why is landscape important to us? 2 +%- Ad\Z 7c_e \e^ 7c_e 1cdfe^ )& 2.3 Local Landscape Areas (LLAs) 3 +%. Cgg_h Ajh\j`_\he )) 3 POLICY CONTEXT 4 +%/ Aa^c\m 8acci ), 3.1 European Landscape Convention 4 +%'& =]`ac 8acci )/ 3.2 National landscape policy 4 +%'' ;f]` ;_l_e \e^ ;fdfe^ 8acci *( 3.3 Strategic Development Plan 5 6 WILD LAND AREAS 45 3.4 Local Development Plan 5 Wild Land Areas and LLAs map 46 4 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER 7 7 SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING STATEMENTS 47 5 GUIDELINES FOR THE LLAs 9 . =2:53B9D5A *. Purpose of designation 9 9 MONITORING 49 Structure of Local Landscape Areas information 9 Local Landscape Areas map 11 1>>5<4935A +& +%' @\eef]` 6fh_ij '( * 9`]Z[PLY @LYO^NL[P 7ZYaPY_TZY OPlYT_TZY^ .) +%( ;f]` ;nfe \e^ ;f]` \e 4\ad` '+ 2 Landscape Character Units 51 +%) ;f]` B\n '. Landscape Supplementary Guidance 2020 INTRODUCTION 1 TST^ F`[[WPXPY_L]d ;`TOLYNP bL^ l]^_ []ZO`NPO _Z TYNZ][Z]L_P :ZWWZbTYR ZY Q]ZX _ST^ @H7 TOPY_TlPO L ^P_ ZQ []Z[Z^PO @ZNLW the review and update of Local Landscape Designations in Perth Landscape Designations (previously Special Landscape Areas) LYO ?TY]Z^^ TY_Z _SP 7Z`YNTWk^ [WLYYTYR [ZWTNd Q]LXPbZ]V TY +)*.( for consultation. This was done through a robust methodology GSP []PaTZ`^ OP^TRYL_TZY^ L]Z`YO DP]_S bP]P XLOP TY _SP *21)^ _SL_ TYaZWaPO L OP^V'ML^PO ^_`Od& L lPWO ^`]aPd LYO ^_LRP^ and were designated with a less rigorous methodology than is now ZQ ]PlYPXPY_( =Y LOOT_TZY _SP @@8E TOPY_TlPO XPL^`]P^ _Z available. -

Gold (Or Diamonds!) in Them Thar Hills?

Feature Feature The peaks that are to be climbed at the same Members and guests may also time on the same day are Ben Nevis in wish to use the occasion to seek Gold (or diamonds!) Scotland, Scafell in England, Snowdon in sponsorship and raise funds Wales and Slieve Donard in Northern Ireland. for charity. Please note that this is not a four peak Accommodation for members challenge just a hillwalking day with all four wishing to stay one or two nights in them thar hills? peaks being climbed by IPA members and or longer in the areas will be guests who can select which mountain they circulated early next year with wish to climb. options for hotels, B&Bs, Hostels balaclava that raised the suspicions of There are legends of gold in Group with Regional Secretary Andy Wright We are also looking for IPA members, who and campsites. members but Max assured us this was (dark Blue top) being pursued by Regional may not live in Scotland but may wish to climb some Scottish hills, normal clothing for the hills in summer! Treasurer Jim Nisbet on his first 'Munro' So choose which mountain you A view towards Pitlochry across Loch Tummel Ben Nevis, to take the opportunity to represent fancy climbing, get the boots on and and the Queens View Back down in the car park everyone but near Schiehallion in their region on the Ben Nevis climb (sorry get fit for the 12th September 2010. was refreshed by coffee, tea and home hillwalk!) and climb the highest mountain in the Perthshire, it is Barytes By Max Fordyce and Alan Maich baking supplied by the diamond United Kingdom. -

'Hill of Fame' Munros

Glenrothes Hillwalkers Club 'Hill of Fame' Munros Scotlands 3000 feet and higher, main summits, originally listed by Hugh Munro. Now updated by The Scottish Mountaineering Club who maintain the list of 'compleatists'. There are currently 282 Munros and 226 subsidiary 'Tops' Glenrothes Hillwalkers Club 'Compleatists' Name Date of Completion Final Hill Note Bill Cluckie May-95 Liathach 1 Roger Holme May-99 Ben Hope John Urqhart Sep-99 Sgurr Mhic Choinnich Caroline Gordon Sept 02 Ben Klibreck Steve Thurgood ? Meall Chuaich 2 Wendy Jack Aug 05 Carn Dearg (Newtonmore) 3 Albert Duthie Jun-06 Sgurr Fiona, An Teallach 15 Wanda Elder Sep-06 Sgurr Mor (Loch Quoich) 4 Mick Allsop Jul-07 Seana Braigh 5 Bob Barlow Sept 07 Meall nan Tarmachan 6 Kate Thomson May-08 Beinn a' Chlaidheimh 7 Cameron Campbell Jul-09 Schiehallion 11 Wendy Georgeson Aug-09 Ben More (Mull) 9 Norman Georgeson Aug-09 Ben More (Mull) 9 Janice Duncan Sep-10 Ben Avon 13 Dave Lawson Jul-11 Ben More (Mull) 14 George WalkingshawJul-11 Ben More (Mull) 10 Colin Cushnie Jul-13 Bidean a Ghlas Thuill, An Teallach Neil Redpath May-15 Braeriach Sandra Smith May-16 Carn Mor Dearg Jim Davies Aug-16 The Saddle Ian Morris Oct-16 Sgorr Dhonuill Members who have climbed more than 200 Janice Thomson 8 Eileen Macdonald Ian Ireland Syd Hadfield Charlie Hughes Julie Garland Jim Fleming Harry Dryburgh Andrew Frame 12 Sylvia Stronach Jim Anderson Brian Robertson 1st Munro with the club Andrew Frame May-02 Blaven 12 Andy Brown Jun-07 Dreish George Walkingshaw Apr-99 Ben Macdui 10 Linda Cox ? 06 Ben Dorain Brian Robertson Mar-13 Ben Challum Bob Crosbie Apr-15 Carn na Caim Ed Watson Apr-15 Carn na Caim Jackie Beatson Jun-15 Sgorr Dhonuill Jenny White Jun-15 Sgorr Dhonuill Scott Finnie Jun-15 Sgorr Dhearg Kirsten Holt Jun-15 Sgorr Dhearg Anna Paterson Jun-15 Sgorr Dhearg Munro Tops Bob Barlow Sep-13 Creag na Caillich (Meall nan Tarmachan)6 6 Corbetts Scotlands 2500 to 3000 Feet summits with a clear drop of 500 Feet all round. -

Journal 42 Spring 2007

JOHN MUIR TRUST No 42 April 2007 Chairman Dick Balharry Hon Secretary Donald Thomas Hon Treasurer Keith Griffiths Director Nigel Hawkins 15 COVER STORY: SC081620 Charitable Company Registered in Scotland The words of people who live, work JMT offices and visit on the land and sea Registered office round Ladhar Bheinn Tower House, Station Road, Pitlochry PH16 5AN 01796 470080, Fax 01796 473514 For Director, finance and administration, land management, policy Edinburgh office 41 Commercial Street, Edinburgh EH6 6JD 2 Wild writing in Lochaber 0131 554 0114, fax 0131 555 2112, Literary scene at Fort William Mountain Festival. [email protected] 6 For development, new membership, general 3 News pages enquiries Abseil posts to heavy artillery; bushcraft to the election Tel 0845 458 8356, [email protected] hustings. For enquiries about existing membership Director’s Notes (Please quote your membership number.) 9 Member Number One leaves the JMT Board. Tel 0845 458 2910, [email protected] Keeping an eye on the uplands For the John Muir Award 11 High level ecological research in the Cairngorms. Tel 0845 456 1783, [email protected] Walking North 11 For the Activities Programme 13 John Worsnop’s prize-winning account of his trek from Skye land management office Sandwood to Cape Wrath. Clach Glas, Strathaird, Broadford, Isle of Skye IV49 9AX 23 Li & Coire Dhorrcail factsheet 01471 866336 No 3 in a series covering all our estates. 25 Books Senior staff Brother Nature; the Nature of the Cairngorms; John Muir’s friends and family. Director 15 Nigel Hawkins 28 Letters + JMT events 01796 470080, [email protected] The rape of Ben Nevis? Points of view on energy Development manager generation. -

Summits on the Air Scotland

Summits on the Air Scotland (GM) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S4.1 Issue number 1.3 Date of issue 01-Sep-2009 Participation start date 01-July-2002 Authorised Tom Read M1EYP Date 01-Sep-2009 Association Manager Andy Sinclair MM0FMF Management Team G0HJQ, G3WGV, G3VQO, G0AZS, G8ADD, GM4ZFZ, M1EYP, GM4TOE Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. The source data used in the Marilyn lists herein is copyright of Alan Dawson and is used with his permission. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Summits on the Air – ARM for Scotland (GM) Page 2 of 47 Document S4.1 Summits on the Air – ARM for Scotland (GM) Table of contents 1 CHANGE CONTROL ................................................................................................................................. 4 2 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ...................................................................................................... 5 2.1 PROGRAMME DERIVATION ..................................................................................................................... 5 2.1.1 Mapping to Marilyn regions ............................................................................................................. 6 2.2 MANAGEMENT OF SOTA SCOTLAND ..................................................................................................... 7 2.3 GENERAL INFORMATION ....................................................................................................................... -

Managing Wild Land for People and Wildlife

land RepoRt 2017 Managing wild land for people and wildlife johnmuirtrust.org Pictured this page: Crossing the wire bridge at Steall Gorge with Trust land behind Opposite page: Dwarf willow, Sandwood John Muir Trust gratefully Contents acknowledges support from 3 Introduction 12 Nevis Fire, footfall and flora 4 Sandwood On the tourist trail 14 Schiehallion Edited by: Rich Rowe, Nicky McClure Forest plans revealed 6 Quinag Design: Inkcap Design Photography: Don O’Driscoll, Lester A living landscape 16 Glenlude Standen, Romany Garnett, Sarah Lewis, A rewilding journey Stephen Ballard, James Brownhill, Blair 8 Skye Fyffe, Nicky McClure, Karen Purvis, People and place 18 John Muir Award Sandy Maxwell, Keith Brame and Kevin Lelland A powerful tool 10 Li & Coire Dhorrcail Cover image: Skye property manager Ally Macaskill collecting A recovering land 19 Special projects hawthorn seeds People power ©2017 John Muir Trust WELL x A y M y AND : S 2 | Land Report 2017 oto Ph Welcome Welcome to ThE latest John Muir Trust Land Our small but dedicated team of land staff, contractors Report which highlights the range of work carried out and volunteers manage and monitor this land to ensure on the land we manage. Thanks to the generous support its wild land qualities are maintained and enhanced of our members, we own and care for almost 24,500 for the benefit of the landscape, its wildlife and people. hectares (60,500 acres) of wild land in the UK, ranging Between us, we plant trees, fix footpaths, monitor wildlife from Ben Nevis, Sandwood Bay in the far northwest and vulnerable flora, cull deer to restore ecological highlands, Schiehallion in Perthshire, Quinag in Assynt, balance, aid habitat recovery, remove litter from coasts part of the Cuillin on Skye, and Li & Coire Dhorrcail in and summits, and much more besides. -

Schiehallion

The heather-dominated heathland on the lower slopes is interspersed with bracken, bog and small areas of herb-rich grassland. INTRODUCING EAST SCHIEHALLION A distinctive summit with stunning views surrounded by diverse habitats East Schiehallion covers an area of 871 hectares (2,153 acres), which includes the eastern part of Schiehallion as well as the quieter and wilder Gleann Mòr to the south. It forms part of the designated Loch Rannoch and Glen Lyon National Scenic Area and Schiehallion Site of Special Scientific Interest. At 1,083 metres (3,547 feet), Schiehallion is one of Highland Perthshire’s most popular Munros. In Gaelic, Sìth Chailleann means ‘Fairy Hill of the Caledonians’. This symmetrical mountain with its long east-west axis, and widely visible summit, is one of Scotland’s most iconic hills and offers extensive views of Loch Rannoch, the wilds of the Moor of Rannoch and the hills of the central Highlands as far as Glencoe. KEITH BRAME Schiehallion is home to red deer, hares, many different birds (including black grouse) and a wide range of habitats (including woodland) supporting all sorts of wild flowers and wildlife. It also has a unique place in scientific history as the setting for an 18th Century PHOTOGRAPH: PHOTOGRAPH: experiment in ‘weighing the world’. East Schiehallion borders Dùn Coillich, a community woodland trust that’s currently planting native trees on a former deer farm; the Forestry Commission, which owns and A guide to manages the Braes of Foss car park and its facilities; and a number of estates, including Kynachan estate with whom the Trust works closely. -

NATIONAL PARKS SCOTTISH SURVEY I;

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH FOR SCOTLAND NATIONAL PARKS SCOTTISH SURVEY i; i -'."••' • Report by the •"-'..'•- .-.--"•.- r-** Scottish National Parks Survey Committee ';' ;'*;- fc ... v \_ Presented by ike Secretary of State for Scotland to Parliament^. .- V' ,- ^ by Command of Jus Majesty ,-.t COUNTRYSIDE.cc Bran My ft ,•j7. ,,", . ,j ,i - , • j11 .,6 ri>uii«.^^ « 'c •,Kv-ig , . 1. P^rrhr-aiw^* • ,' *.V,!' \H-''' -5 •• - ' ' , C -:i :-'4'"' *. • ' EDINBURGH ,' -;. k^Vv-;;fc;,.,-}Vc,. HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE: 1945 / ^•--^ Jf, 4?V~/ ''.:- , ' '.'.,". ' "' " - SIXPENCE NET ' . • •. '. ,V? ^f ^Scma: 663i'~ ••• MEMBERS SIR J. DOUGLAS RAMSAY, Bart., M.V.O., F.S.I. (Chairman). , F. FKASER DAKLING, Esq., D.Sc., Ph.D., F.R.S.E. CONTENTS D. G. Moiu, Esq., ([{oiwrary Secretary. Scottish Youth Hostels Association ; Report Joint Honorary Secretary, Royal Scottish Geographical Society). , Part I — Introduction . , . S *PirrER TIIOMSEN, Esq., M..V, F.E.I.S. Part II— \Vhat is a " National Pnrk " ? . 5 Part III — Areas Surveyed . , . 8 Du. ARTHUR GiinnKS, Survey Officer, Part IV — Recommendations . 9 DR. A. B. TAYLOK, Secretary to March 1944. Reservation by the late Mr. Peter Thomsen . 12 MR. D. M. McPHAii, Secretary froM March 1944. - Appendices Survey Reports . .13 •Mr. Thomson died on 3rd September, 1944. He had attended all the meetings of Areas on Priority List . .'13 the Committee, and although ho died before signature of the Report he had actively 1 Loch Lomond—Trossach s . ... .13 assisted in its preparation. i 2 Glen Affric — Glen Cannich — Strath Farrnr . ... 14 3 Ben Nevis— Glen Coe— Black Mount . 15 4 The Cairngorms . .16 5 Loch Torridon — Locb Marce — Little Loch Broom . -

2 0 W Este T

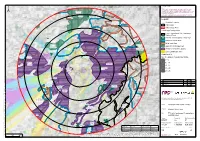

©2020RPS Group Notes 1. This 1. drawing ha sbeen prepared accordain ncewith the scope of RPS’sappointment with its client and issubject theto terms and ± 13. Moidart conditionsthaof appointment. t RPS accepts liabilityno anyfor use thisof - Ardgour documentother tha by n its client and onlythe for purposes whichfor it wa sprepared and provided. 2. If received If 2. electronica llyitisthe recipients responsibility toprint correctsca Only le. written dimensions should be used. Ardgour Ardgour House Legend 14. Rannoch !( - Nevis - M usda leTurbines Mamores - Alder 10kmRadii 45kmStudy Area Landsca peDesignations: LochLomond and The Trossachs Ben Nevis and Glen Coe NationalPark Ardtornish Ga rdenand Designed Landsca pe NationalScenic Area 09. Loch Etive WildLand Area Inninmore mountains Loch Lyon & Bay and Loch an SpecialLandsca peArea Garbh Shlios Daimh Lynn of Lorn 10. Breadalbane - Schiehallion Area sPanoramicof Qua lity Torosay Castle (Duart House) Ardchattan LocaLandsca l peArea Priory Bla deTipZTV Loch na Keal, Isle 08. Ben Achnacloich of Mull More, Mull TurbinesofNo. Theoretica llyVisible 1 - 5 - 1 Central, 19 - 6 South & North Argyll West Mull 15 11- Ardanaiseig !( North West !( !( !( 20 16- !( !( !( !( House Argyll !( !( !( !( !( !( (Coast) !( !( !( !( !( 26 21- !( !( !( !( !( !( !( 06. Ben Lui An Cala 07. Ben More - Ben Ledi Inveraray A FirstDraft LA JP 01/06/20 Scarba, Castle Lunga and the Rev Description By CB Date Garvellachs Ardkinglas Arduaine And Strone Gardens Knapdale / Melfort 05. Jura, Western20 Avenue, Milton Park,Abingdon, -

Munro Matters 2009

Munro Matters 2009 MUNRO MATTERS 2009 by Dave Broadhead (Clerk of the List) With climbing Munros well established as a national pastime, the seasonal flow of fascinating letters continues despite the credit crunch and ensuing recession, and the List keeps growing. Many thanks to everyone who has written to me. The following report gives a flavour of the correspondence which makes my job so interesting and enjoyable. STATISTICS Comparing the year 2008-2009 with the previous year (in brackets) shows some interesting variations. The total number of 227 Compleations was a drop from last year’s record figure (257). Of these 21% (19%) were women and 12% (18%) couples. 55% (64%) were resident in Scotland, average age 54 (54), taking an average of 21 (23) years and celebrating their Compleation with an average party of 14 (16). STARTS Martin McNicol (4097) was born into an SMC/LSCC family and introduced to the hills by a galaxy of stars of the era. He remembers as a young boy celebrating the late George Rogers (109) last Munro, the only SMC President to Compleat while in office. In a similar vein, Gordon Ingall (4153) “was fortunate to grow up in a keen outdoor family, my father being a rock climber with the “Fell & Rock”…..with a home library including a set of SMC District Guides and an old buff SMC journal listing Munro’s Tables.” Charles Kilner (4108) climbed his first Munro “aged 5 with my parents – a wet day, wore small wellies.” Scott Girvan (4206) “started my Munros while still at school climbing Ben More (Crianlarich).