Storage Characteristics of Three Cultivars of Yellow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ripley Farm Seedling Sale 2021 Plant List (All Plants Are Subject to Availability)

Ripley Farm Seedling Sale 2021 Plant List (All plants are subject to availability) Family/Category Type of vegetable Variety/description Pot size Brassicas Broccoli Belstar 6 pack Brussels Sprouts Dagan 6 pack Cabbage, green Farao 6 pack Cabbage, red Ruby Ball 6 pack Cauliflower White 6 pack Kale Russian 6 pack Kale Curled Scotch 6 pack Kale Scarlet (curled) 6 pack Kale Russian/Curly Mix 6 pack Kohlrabi Green/Purple Mix 6 pack Pac Choi (Bok Choy) Mei Qing Choi 6 pack Cucurbits Cucumbers, slicing General Lee 3 plants/3" pot Cucumbers, slicing Diva 3 plants/3" pot Cucumbers, slicing Sliver Slicer 3 plants/3" pot Cucumbers, pickling H-19 Littleleaf 3 plants/3" pot Cucumbers, specialty Lemon 3 plants/3" pot Pumpkin Jack-B-Little (edible) 3 plants/3" pot Pumpkin Long Pie (edible) 3 plants/3" pot Pumpkin New England Pie (edible) 3 plants/3" pot Pumpkin Howden (Jack-O-Lantern) 3 plants/3" pot Summer Squash Yellow Patty Pan 3 plants/3" pot Summer Squash Yellow straightneck squash 3 plants/3" pot Watermelon Sugar Baby 3 plants/3" pot Winter Squash Butterbaby (mini butternut) 3 plants/3" pot Winter Squash Buttercup 3 plants/3" pot Winter Squash Butternut (full size) 3 plants/3" pot Winter Squash Delicata 3 plants/3" pot Winter Squash Ornamental Mix (orange, white, blue, bumpy) 4 pack Winter Squash Sunshine Kabocha 3 plants/3" pot Zucchini Dunja (dark green) 3 plants/3" pot Eggplant Eggplant Asian, dark purple 3" pot Greens/Herbs Chard, Swiss Fordhook Giant (green) 6 pack Chard, Swiss Red/Green Mix 6 pack Dill Bouquet 6 pack Fennel Preludio 6 pack -

Larworks at WMU

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1998 Spatial Analysis of Agricultural Cucurbita Sp. Varieties in the Eastern Broadleaf Province Kathleen M. Baker Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Kathleen M., "Spatial Analysis of Agricultural Cucurbita Sp. Varieties in the Eastern Broadleaf Province" (1998). Master's Theses. 4789. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4789 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPATIAL ANALYSIS OF AGRICULTURAL CUCURBITA SP. VARIETIES IN THE EASTERN BROADLEAF PROVINCE by Kathleen M. Baker A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Geography Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1998 Copyright by Kathleen M. Baker 1998 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you, first and foremost, to my friends and family who have added the word Cucurbitaceaeto their vocabulariesfor my sake. My thesis advisor, Dr. Rolland Fraser, and committee members, Dr. IlyaZaslavsky and Dr. Oscar Horst, have been marvelous, what can I say? Even when inedible cucurbits made you laugh, you tempered my crazy ideas withgood sense. To the grad students, faculty andstaff at Western, especiallythose of you who offered suggestionsalthough pumpkinswere far from your number one priority - you've been great, guys. May lightning never strikeyou. -

Dianne Onstad

revised and expanded edition WHOLE FOODS COMPANION a guide for adventurous cooks, curious shoppers, and lovers of natural foods D IA NN E O NSTA D VEGETABLES SUMMER SQUASH VARIETIES be grown in America and Europe. Eaten in the summer when immature and thin-skinned, it is usually sliced Choose summer squashes that are tender and fresh into rounds and steamed or boiled and served with looking, with skin that is soft enough to puncture with a butter, salt, pepper, and herbs such as tarragon, dill, or fingernail. They perish easily, so store them in the refriger- marjoram. ator and use as soon as possible. Pattypan oror scallop squash looks rather like a thick, Chayote ((Sechium edule ) is a pear-shaped squash native round pincushion with scalloped edges. They are their to Mexico and Central America (its name is from the best when they do not exceed four inches in diameter Aztec Nahuatl chayotl ). Also known as mango squash, and are pale green rather than their mature white or pepinello, and vegetable pear, the chayote has soft, cream. Their flesh has a somewhat buttery taste, and pale skin that varies from creamy white to dark green. the skin, flesh, and seeds are all edible. Female fruit is smooth-skinned and lumpy, with slight Spaghetti squash ((Cucurbita pepo)) is a lla argarge, oblong ridges. It is fleshier and preferred over the male fruit, summer squash with smooth, lemon-yellow skin. Once which is covered with warty spines. Although they are cooked, the creamy golden flesh separates into miles of furrowed and slightly pitted by nature, they should not swirly, crisp-tender, spaghetti-like strands. -

Crop Profile for Squash in Florida

Crop Profile for Squash in Florida Prepared: August 2001 Prepared: October 2002 General Production Information ● Florida is ranked second nationally in the production of fresh market squash (2). ● Florida squash growers produce primarily summer squashes (Cucurbita pepo), such as crookneck squash, straightneck squash, scallop squash, and zucchini squash. Growers also produce some winter squashes (4), such as acorn (C. pepo), butternut squash (C. moschata), and spaghetti squash (C. pepo). There is some commercial production of calabaza or Cuban squash (Cucurbita moschata) in South Florida, and Floridians produce a variety of tropical squashes and related cucurbits [such as pumpkin (Cucurbita spp.), chayote (Sechium edule), banana squash (Cucurbita maxima), and gourds (Lagenaria spp. and Luffa spp.)] in home gardens, but this profile includes only summer and winter squashes (12,13,14,15,16). ● Cash receipts for squash produced in Florida in 1999-2000, which totaled $45.9 million, accounted for approximately 20 percent of the total U.S. cash receipts for squash production (2,8). ● Of Florida's vegetable crops, squash is ranked 6th in terms of harvested acres and 7th in terms of total value (4). ● During the 1999-2000 crop year, Florida squash growers planted 12,100 acres and harvested 11,800 acres, producing a total of 3.45 million bushels (145 million pounds). Average yield was 293 bushels per acre (12,310 pounds per acre) and total value of the crop was $45.9 million. During the previous year, 13,000 acres of squash were planted and 3.53 million bushels (148 million pounds), with a total value of $53.8 million, were produced on 12,600 harvested acres, yielding 280 bushels per acre (7). -

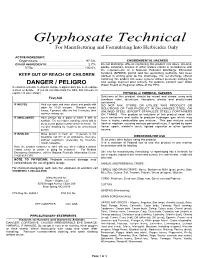

Glyphosate Technical for Manufacturing and Formulating Into Herbicides Only

Glyphosate Technical For Manufacturing and Formulating Into Herbicides Only ACTIVE INGREDIENT: Glyphosate ……………………………… 97.3% ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS OTHER INGREDIENTS:…………………………………. 2.7% Do not discharge effluent containing this product into lakes, streams, TOTAL : ………………………………………………. 100.0% ponds, estuaries, oceans or other waters unless in accordance with the requirements of a National Pollutant Discharge Eliminator Systems (NPDES) permit and the permitting authority has been KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN notified in writing prior to the discharge. Do not discharge effluent containing this product into sewer systems without previously notifying the local sewage treatment plant authority. For guidance contact your State DANGER / PELIGRO Water Board or Regional Office of the EPA. Si usted no entiende la etiqueta, busque a alguien para que se la explique a usted en detalle. (If you do not understand the label, find someone to explain it to you in detail.) PHYSICAL or CHEMICAL HAZARDS Solutions of this product should be mixed and stored using only First Aid stainless steel, aluminum, fiberglass, plastic and plastic-lined containers. IF IN EYES Hold eye open and rinse slowly and gently with DO NOT MIX, STORE OR UTILIZE THIS PRODUCT OR water for 15-20 minutes. Remove contact SOLUTIONS OF THIS PRODUCT IN GALVANIZED STEEL OR lenses, if present, after the first 5 minutes, then UNLINED STEEL (EXCEPT STAINLESS STEEL) CONTAINERS continue rinsing eye OR TANKS. This product or solutions of this product react with IF SWALLOWED Have person sip a glass of water if able to such containers and tanks to produce hydrogen gas which may swallow. Do not induce vomiting unless told to form a highly combustible gas mixture. -

Gene List for Cucurbita Species, 2004

Gene List for Cucurbita species, 2004 Harry S. Paris A.R.O., Newe Ya’ar Research Center, Ramat Yishay 30-095 (Israel) Rebecca Nelson Brown Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331 (U.S.A.) A complete list of genes for Cucurbita species was last published 12 years ago (33). Since then, only updates have been published (72, 73). The genus Cucurbita L. contains 12 or 13 species (50). As far as is known, all have a complement of 20 pairs of chromosomes (2n = 40). This new gene list for Cucurbita contains much more detail concerning the sources of information, being modeled after the one for cucumber presented by Wehner and Staub (96) and its update by Xie and Wehner (100). In order to more easily allow confirmation of previous work and as a basis for further work, information has been added concerning the genetic background of the parents that had been used for crossing. Thus, in addition to the species involved, the cultivar-group (for C. pepo), market type (for C. maxima, C. moschata), and/or cultivar name are included in the description wherever possible. Genes affecting phenotypic/morphological traits are listed in Table 1. The data upon which are based identifications and concomitant assignment of gene symbols vary considerably in their content. No attempt is made here to assess the certainty of identifications, but gene symbols have been accepted or assigned only for cases in which at least some data are presented. The genes that are protein/isozyme variants are listed in Table 2. It can be seen from Tables 1 and 2 that a large number of genes, 65, have been identified for C. -

Vegetable Book

The Wright Way Farm Veggie Book What to do with your fresh produce! From using it fresh to freezing, blanching or dehydrating, this will be your guide to answering questions on “What do I do with this?” Table of Contents Vegetable Care ...........................................................................................................................................................6 Acorn Squash ..............................................................................................................................................................6 Arugula .......................................................................................................................................................................7 Asparagus ...................................................................................................................................................................8 Basil ............................................................................................................................................................................9 Beans ....................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Beets ........................................................................................................................................................................ 11 Broccoli ................................................................................................................................................................... -

AN ABSTRACT of the THESIS of Rebecca Nelson Brown for The

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Rebecca Nelson Brown for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Horticulture presented on July 2. 2001. Title: Traditional and Molecular Approaches to Zucchini Yellow Mosaic Virus Resistance in Cucurbita Abstract approved: 7 James R. Myers 7 Zucchini yellow mosaic virus (ZYMV) is an important disease of Cucurbita worldwide. Resistant cultivars are the best means of control. ZYMV resistance is quantitative in the wild species C. ecuadorensis, and is controlled by at least three genes in tropical C moschata. Very little molecular work has been done in Cucurbita, and no markers are available to assist in selecting for ZYMV resistance genes. The objectives of this research were threefold: to develop molecular markers for use in breeding for ZYMV resistance, to develop a framework map of Cucurbita, and to transfer ZYMV resistance from C. ecuadorensis to C. maxima 'Golden Delicious'. The identification of a DNA marker linked to ZYMV resistance from C moschata TSIigerian Local' was attempted using random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis of resistant and susceptible bulks from the crosses C moschata 'Waltham Butternut' x CWaltham Butternut' x TSIigerian Local'). No marker consistently linked to ZYMV resistance was identified. Marker polymorphism was 14% between the parents. The cross C pepo A0449 x (A0449 x TSTigerian Local') was used as the mapping population to construct the framework map. The completed map consists of 153 loci in 29 linkage groups covering 1,981 cM. Approximately 75% of the Cucurbita genome is covered. Three morphological traits, two quantitative trait loci and a putative secondary ZYMV resistance gene have been placed on the map; an additional eight traits and nine RAPD markers remain unlinked. -

Squash and Pumpkins Squash and Pumpkins Are Among the Most Popular and Productive Warm-Season Vegetables in Louisiana

Squash and Pumpkins Squash and pumpkins are among the most popular and productive warm-season vegetables in Louisiana. In Summer Squash many cases, a few plants will supply enough produce for Summer squash generally grow in bush forms. The an entire family. Squash and pumpkins belong to the gourd fruit are eaten young and tender. In general your fingernail family called the “cucurbits.” They are believed to be native should be able to easily penetrate the skin. Most chefs to Central America (especially pumpkins). Most types are prefer to cook or prepare the squash fruit when it is still good sources of vitamin A, but they are mainly desired immature. Yellow types are generally harvested 6 inches in for their flavor and texture. Squash and pumpkins can be length or less. Green and yellow zucchini can be harvested combined with spices to create savory soups and soufflés up to 10 inches in length. Summer squash require 45 to or combined with cream and sugar to make pies and 50 days from planting until harvest. If planted during the sweet breads. For gardeners on carbohydrate restricted summer, squash mature in 35 to 40 days. Summer squash diets, try using spaghetti squash or yellow and green are typically planted March through August. Space summer zucchini sliced thick in place of noodles. squash 18 inches to 3 feet apart on a row. These crops thrive in warm weather. They will tolerate Summer squash types typically grown in Louisiana some low temperatures but are very frost sensitive. Seeds include: need a soil temperature of at least 60° F to germinate. -

Harvest for the Hungry Garden 2020 Plant Sale Vegetable Varieties

Harvest for the Hungry Garden 2020 Plant Sale Vegetable Varieties Basil seed source Italian Pesto Genovese Basil Italian basil, perfect for pesto https://www.reneesgarden.com/products/basil-profumo-di-genova Lettuce Leaf Basil extra large, clinkled leaves https://www.rareseeds.com/store/herbs/basil/basil-lettuce-leaf Thai Basil fragrant and sweet, great for Thai https://www.rareseeds.com/store/vegetables/thai-varieties/basil-thai-sweet cooking Chard Rainbow Chard beautiful multi-colored variety https://www.highmowingseeds.com/organic-non-gmo-improved-rainbow-bl-chard.html Cucumbers Armenian Cucumber nice mild flavor with few seeds, is https://www.rareseeds.com/store/vegetables/cucumbers/armenian-yard-long-cucumber actually a melon! Bush Slicer dwarf bush variety - great for container https://www.reneesgarden.com/products/cucumber-bush-slicer gardening Chelsea Prize English cucumber 12-15 inches, non- https://www.reneesgarden.com/products/cucumber-english-chelsea-prize bitter, thin skin Garden Oasis Delicate meditarranean variety, 5-8", https://www.reneesgarden.com/products/cucumber-garden-oasis very thin skin Homemade Pickles high yielding pickling cucumber https://www.botanicalinterests.com/product/Homemade-Pickles-Cucumber-Seeds Lemon Cucumber round yellow cucumber, citrusy non- https://www.reneesgarden.com/products/cucumber-heirloom-lemon bitter flavor Persian Green Fingers A garden favorite! Delicious 4-5" baby https://www.reneesgarden.com/products/cucumber-baby-persian-green-fingers cucumbers Tasty Green Japanese slender, long shape, -

Gene List for Cucurbita Species, 2014

1 Gene List for Cucurbita species, 2014 Harry S. Paris A.R.O., Newe Ya‘ar Research Center, Ramat Yishay 30-095 (Israel) Les D. Padley Jr. Syngenta Seeds, Rogers Brand Vegetable Seeds, 10290 Greenway Road, Naples, FL 34114 (U.S.A.) The genus Cucurbita L. contains 12 or 13 species (56). As far as is known, all have a complement of 20 pairs of chromosomes (2n = 40) (111). This gene list for Cucurbita contains detailed sources of information, being modeled after the one for cucumber presented by Wehner and Staub (109) and its update by Xie and Wehner (115). In order to more easily allow confirmation of previous work and as a basis for further work, information has been included concerning the genetic background of the parents that had been used for crossing. Thus, in addition to the species involved, the cultivar-group for C. pepo L. (60), market type for C. maxima Duchesne and C. moschata Duchesne (26), and/or cultivar name are included in the description wherever possible. The names and symbols of the genes, together with a concise description of their phenotypic effects, are listed alphabetically below. The data upon which are based identifications and concomitant assignment of gene symbols vary considerably in their content. No attempt is made here to assess the certainty of identifications, but gene symbols have been accepted or assigned only for cases in which at least some data are presented. Approximately 70 genes have been identified for C. pepo, 30 for C. moschata, and 19 for C. maxima. For the interspecific cross of C. -

Squash, Zucchini—Cucurbita Pepo L.1 James M

HS675 Squash, Zucchini—Cucurbita pepo L.1 James M. Stephens2 Zucchini squash in recent years has overtaken other types of summer squash in popularity as a fresh and cooked vegetable. It is found in almost every garden throughout Florida and on salad bars everywhere as a fresh sliced delicacy. In Windsor, a small community in North Central Florida, the Annual Zucchini Festival someday may be the town’s main claim to fame. Description Zucchini is represented by several named varieties (culti- vars). Fruits of this member of the Italian marrow squashes grow most commonly in cylindrical shapes, but also in round and intermediate shapes. Fruit color varies from a Figure 1. Zucchini squash. green so dark as to be near black, to lighter shades of green Credits: Pablo Oliveri, CC BY-SA 2.5 both with and without stripes, all the way to tones of yellow. Many are highlighted with various degrees of speckling. Like other members of the summer squash group, the zuc- chini plant has the bush habit rather than the vining habit Cylindrical fruits range in average size from the 5–6 inch of the winter squashes. However, within the bush habit, ‘Caserta’ to the longer varieties such as ‘Cocozelle’ that there is a fairly wide range of variations in general plant reaches 14–16 inches in length. Most varieties average 3–4 character, primarily in density and arrangement of leaves. inches in diameter. Varieties may be classified as to bush habit, with a rating Gardeners like to see just how big their zucchinis will of (1) given to the open habit, where the leaves are more grow if left on the plant.