National Energy Board

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Municipal Guide

Municipal Guide Planning for a Healthy and Sustainable North Saskatchewan River Watershed Cover photos: Billie Hilholland From top to bottom: Abraham Lake An agricultural field alongside Highway 598 North Saskatchewan River flowing through the City of Edmonton Book design and layout by Gwen Edge Municipal Guide: Planning for a Healthy and Sustainable North Saskatchewan River Watershed prepared for the North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance by Giselle Beaudry Acknowledgements The North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance would like to thank the following for their generous contributions to this Municipal Guide through grants and inkind support. ii Municipal Guide: Planning for a Healthy and Sustainable North Saskatchewan Watershed Acknowledgements The North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance would like to thank the following individuals who dedicated many hours to the Municipal Guide project. Their voluntary contributions in the development of this guide are greatly appreciated. Municipal Guide Steering Committee Andrew Schoepf, Alberta Environment Bill Symonds, Alberta Municipal Affairs David Curran, Alberta Environment Delaney Anderson, St. Paul & Smoky Lake Counties Doug Thrussell, Alberta Environment Gabrielle Kosmider, Fisheries and Oceans Canada George Turk, Councillor, Lac Ste. Anne County Graham Beck, Leduc County and City of Edmonton Irvin Frank, Councillor, Camrose County Jolee Gillies,Town of Devon Kim Nielsen, Clearwater County Lorraine Sawdon, Fisheries and Oceans Canada Lyndsay Waddingham, Alberta Municipal Affairs Murray Klutz, Ducks -

Brazeau River Gas Plant

BRAZEAU RIVER GAS PLANT Headquartered in Calgary with operations focused in Western Canada, KEYERA operates an integrated Canadian-based midstream business with extensive interconnected assets and depth of expertise in delivering midstream energy solutions. Image input specifications Our business consists of natural gas gathering and processing, Width 900 pixels natural gas liquids (NGLs) fractionation, transportation, storage and marketing, iso-octane production and sales and diluent Height 850 pixels logistic services for oil sands producers. 300dpi We are committed to conducting our business in a way that 100% JPG quality balances diverse stakeholder expectations and emphasizes the health and safety of our employees and the communities where we operate. Brazeau River Gas Plant The Brazeau River gas plant, located approximately 170 kilometres southwest of the city of Edmonton, has the capability PROJECT HISTORY and flexibility to process a wide range of sweet and sour gas streams with varying levels of NGL content. Its process includes 1968 Built after discovery of Brazeau Gas inlet compression, sour gas sweetening, dehydration, NGL Unit #1 recovery and acid gas injection. 2002 Commissioned acid gas injection system Brazeau River gas plant is located in the West Pembina area of 2004 Commissioned Brazeau northeast Alberta. gas gathering system (BNEGGS) 2007 Acquired 38 kilometre sales gas pipeline for low pressure sweet gas Purchased Spectra Energy’s interest in Plant and gathering system 2015 Connected to Twin Rivers Pipeline 2018 Connected to Keylink Pipeline PRODUCT DELIVERIES Sales gas TransCanada Pipeline System NGLs Keylink Pipeline Condensate Pembina Pipeline Main: 780-894-3601 24-hour emergency: 780-894-3601 www.keyera.com FACILITY SPECIFICATIONS Licensed Capacity 218 Mmcf/d OWNERSHIP INTEREST Keyera 93.5% Hamel Energy Inc. -

Northwest Territories Territoires Du Nord-Ouest British Columbia

122° 121° 120° 119° 118° 117° 116° 115° 114° 113° 112° 111° 110° 109° n a Northwest Territories i d i Cr r eighton L. T e 126 erritoires du Nord-Oues Th t M urston L. h t n r a i u d o i Bea F tty L. r Hi l l s e on n 60° M 12 6 a r Bistcho Lake e i 12 h Thabach 4 d a Tsu Tue 196G t m a i 126 x r K'I Tue 196D i C Nare 196A e S )*+,-35 125 Charles M s Andre 123 e w Lake 225 e k Jack h Li Deze 196C f k is a Lake h Point 214 t 125 L a f r i L d e s v F Thebathi 196 n i 1 e B 24 l istcho R a l r 2 y e a a Tthe Jere Gh L Lake 2 2 aili 196B h 13 H . 124 1 C Tsu K'Adhe L s t Snake L. t Tue 196F o St.Agnes L. P 1 121 2 Tultue Lake Hokedhe Tue 196E 3 Conibear L. Collin Cornwall L 0 ll Lake 223 2 Lake 224 a 122 1 w n r o C 119 Robertson L. Colin Lake 121 59° 120 30th Mountains r Bas Caribou e e L 118 v ine i 120 R e v Burstall L. a 119 l Mer S 117 ryweather L. 119 Wood A 118 Buffalo Na Wylie L. m tional b e 116 Up P 118 r per Hay R ark of R iver 212 Canada iv e r Meander 117 5 River Amber Rive 1 Peace r 211 1 Point 222 117 M Wentzel L. -

Quarrernary GEOLOGY of MINNESOTA and PARTS of ADJACENT STATES

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Ray Lyman ,Wilbur, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director P~ofessional Paper 161 . QUArrERNARY GEOLOGY OF MINNESOTA AND PARTS OF ADJACENT STATES BY FRANK LEVERETT WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY FREDERICK w. SARDE;30N Investigations made in cooperation with the MINNESOTA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1932 ·For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. CONTENTS Page Page Abstract ________________________________________ _ 1 Wisconsin red drift-Continued. Introduction _____________________________________ _ 1 Weak moraines, etc.-Continued. Scope of field work ____________________________ _ 1 Beroun moraine _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 47 Earlier reports ________________________________ _ .2 Location__________ _ __ ____ _ _ __ ___ ______ 47 Glacial gathering grounds and ice lobes _________ _ 3 Topography___________________________ 47 Outline of the Pleistocene series of glacial deposits_ 3 Constitution of the drift in relation to rock The oldest or Nebraskan drift ______________ _ 5 outcrops____________________________ 48 Aftonian soil and Nebraskan gumbotiL ______ _ 5 Striae _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 48 Kansan drift _____________________________ _ 5 Ground moraine inside of Beroun moraine_ 48 Yarmouth beds and Kansan gumbotiL ______ _ 5 Mille Lacs morainic system_____________________ 48 Pre-Illinoian loess (Loveland loess) __________ _ 6 Location__________________________________ -

Thundering Spirit" Call to Order Opening Prayer: Treaty Six Lead Elder Jon Ermineskin 9:00 A.M

ASSEMBLY OF FIRST NATIONS WATER RIGHTS CONFERENCE 2012 “Asserting our Rights to Water” Monday, March 5, 2012 7:00 a.m. Registration and continental breakfast 8:30 a.m. Drum Treaty 6 drum group "Thundering Spirit" Call to Order Opening prayer: Treaty Six Lead Elder Jon Ermineskin 9:00 a.m. Welcoming remarks: Host Chief Ron Morin, Enoch Cree Nation Treaty 6 Grand Chief Cameron Alexis 9:15 a.m. Opening remarks: Bringing national attention and awareness to Indigenous water rights Portfolio Regional Chief: Regional Chief Eric Morris (YT) 9:45 a.m. Opening Remarks: Indigenous rights to water – our sacred duties and responsibilities National Chief Shawn A-in-chut Atleo 10:00 a.m. Health Break Monday, March 5, 2012 10:15 a.m. Plenary Panel Presentation: Advancing our Full Understanding of the Inherent and Treaty Right to Water The nature of water rights: Dr. Leroy Littlebear, University of Lethbridge Community-based struggles for water rights: Chief Eli Mandamin, Iskatewizaagegan Independent First Nation Exercising Indigenous Water Rights - BC: Chief Bob Chamberlin, Kwicksutaineuk-Ah-Kwaw-Ah-Mish First Nation; Vice-President of Union of BC Indian Chiefs; Andrea Glickman, Policy Analyst, UBCIC., Legal dimensions for Alberta First Nations: Clayton D Leonard, MacPherson, Leslie &Tyerman LLP 12:00 Lunch (provided on site) p.m. Presentation: The Human Right to Water - Maude Barlow 1:00 p.m. Special Presentation: IikaatowapiwaNaapiitahtaan: The Old Man River is Sacred Chief Gayle Strikes With a Gun; Iitamyapii (Looks From Above): Byron Jackson; Saa-Ku-Waa- Mu-Nii (Last Otter): Councillor Fabian North Peigan; Moderator: PiiohkSooPanski (Comes Singing), Councillor Angela Grier, Piikani Nation 1:30 p.m. -

RURAL ECONOMY Ciecnmiiuationofsiishiaig Activity Uthern All

RURAL ECONOMY ciEcnmiIuationofsIishiaig Activity uthern All W Adamowicz, P. BoxaIl, D. Watson and T PLtcrs I I Project Report 92-01 PROJECT REPORT Departmnt of Rural [conom F It R \ ,r u1tur o A Socio-Economic Evaluation of Sportsfishing Activity in Southern Alberta W. Adamowicz, P. Boxall, D. Watson and T. Peters Project Report 92-01 The authors are Associate Professor, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton; Forest Economist, Forestry Canada, Edmonton; Research Associate, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton and Research Associate, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton. A Socio-Economic Evaluation of Sportsfishing Activity in Southern Alberta Interim Project Report INTROI)UCTION Recreational fishing is one of the most important recreational activities in Alberta. The report on Sports Fishing in Alberta, 1985, states that over 340,000 angling licences were purchased in the province and the total population of anglers exceeded 430,000. Approximately 5.4 million angler days were spent in Alberta and over $130 million was spent on fishing related activities. Clearly, sportsfishing is an important recreational activity and the fishery resource is the source of significant social benefits. A National Angler Survey is conducted every five years. However, the results of this survey are broad and aggregate in nature insofar that they do not address issues about specific sites. It is the purpose of this study to examine in detail the characteristics of anglers, and angling site choices, in the Southern region of Alberta. Fish and Wildlife agencies have collected considerable amounts of bio-physical information on fish habitat, water quality, biology and ecology. -

Brazeau Subwatershed

5.2 BRAZEAU SUBWATERSHED The Brazeau Subwatershed encompasses a biologically diverse area within parts of the Rocky Mountain and Foothills natural regions. The Subwatershed covers 689,198 hectares of land and includes 18,460 hectares of lakes, rivers, reservoirs and icefields. The Brazeau is in the municipal boundaries of Clearwater, Yellowhead and Brazeau Counties. The 5,000 hectare Brazeau Canyon Wildland Provincial Park, along with the 1,030 hectare Marshybank Ecological reserve, established in 1987, lie in the Brazeau Subwatershed. About 16.4% of the Brazeau Subwatershed lies within Banff and Jasper National Parks. The Subwatershed is sparsely populated, but includes the First Nation O’Chiese 203 and Sunchild 202 reserves. Recreation activities include trail riding, hiking, camping, hunting, fishing, and canoeing/kayaking. Many of the indicators described below are referenced from the “Brazeau Hydrological Overview” map locat- ed in the adjacent map pocket, or as a separate Adobe Acrobat file on the CD-ROM. 5.2.1 Land Use Changes in land use patterns reflect major trends in development. Land use changes and subsequent changes in land use practices may impact both the quantity and quality of water in the Subwatershed and in the North Saskatchewan Watershed. Five metrics are used to indicate changes in land use and land use practices: riparian health, linear development, land use, livestock density, and wetland inventory. 5.2.1.1 Riparian Health 55 The health of the riparian area around water bodies and along rivers and streams is an indicator of the overall health of a watershed and can reflect changes in land use and management practices. -

Keeping Alberta Wild Since 1968 Milner Public Library Suites 628 – 7 Sir Winston Churchill Square Edmonton, Alberta T5J 2V4

Milner Public Library Suites 628 – 7 Sir Winston Churchill Square Edmonton, Alberta T5J 2V4 February 18, 2021 BRIEFING NOTE: Open-pit coal mining in the North Saskatchewan watershed and impacts to the City of Edmonton Prepared by CPAWS Northern Alberta for Edmonton City Council Executive Summary ● On June 1, 2020 the Government of Alberta rescinded the Coal Development Policy for Alberta (Coal Policy) ● No public consultation was conducted on the removal of the policy ● The recent reinstatement of the coal policy does not eliminate the risk of open pit coal mining and its impacts to Edmonton’s source of drinking water (the Bighorn region) ● While the policy was removed a large number of new leases were granted in the Bighorn ● The Valory Blackstone project was granted exploration permits (meaning they can build roads and drill test pits) that may be allowed to go forward as soon as this spring ● There is still no land-use plan for the North Saskatchewan Region to manage cumulative impacts of overlapping industrial and recreational land uses ● Any replacement of the Coal Policy should include full public and Indigenous consultation and the City of Edmonton should be considered as a major stakeholder ● Several communities have taken a stance against the removal of the Coal Policy and have requested that all exploration and development activities are stopped until robust consultation has been conducted on a replacement for the Policy Overview ● The 1976 Coal Policy, developed over years of work and public consultation, outlined four categories for coal development. Category 1 prohibited mining and Category 2 restricted open-pit coal mines. -

Bighorn Backcountry Public Land Use Zones 2019

Edson 16 EDMONTON Hinton 47 22 Jasper 39 734 Bighorn Backcountry PLUZs 2 22 National Bighorn The Bighorn Backcountry is managed to ensure the Backcountry Park protection of the environment, while allowing responsible 11 and sustainable recreational use. The area includes more than Rocky 11 5,000 square kilometres (1.2 million acres) of public lands east Mountain House 54 of Banff and Jasper National Parks. 734 27 The Bighorn Backcountry hosts a large variety of recreational Banff National 22 activities including camping, OHV and snow vehicle use, hiking, shing, Park hunting and cycling. CALGARY 1 It is your responsibility to become familiar with the rules and activities allowed in this area before you visit and to be informed of any trail closures. Please refer to the map and chart in this pamphlet for further details. Visitors who do not follow the rules could be ned or charged under provincial legislation. If you have any concerns about the condition of the trails and campsites or their appropriate use, please call Alberta Environment and Parks at the Rocky Mountain House Ofce, 403-845-8250. (Dial 310-0000 for toll-free service.) For current trail conditions and information kiosk locations, please visit the Bighorn Backcountry website at www.alberta.ca Definitions for the Bighorn Backcountry Motorized User ✑ recreational user of both off-highway vehicles and snow vehicles. Equestrian User or ✑ recreational user of both horses and/or mules, used for trail riding, pack Equine horse, buggy/cart, covered wagon or horse-drawn sleigh. Non-Motorized User ✑ recreational user which is non-motorized except equestrian user or equine where specified or restricted. -

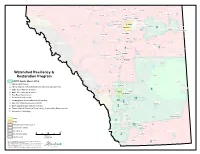

Watershed Resiliency and Restoration Program Maps

VU32 VU33 VU44 VU36 V28A 947 U Muriel Lake UV 63 Westlock County VU M.D. of Bonnyville No. 87 18 U18 Westlock VU Smoky Lake County 28 M.D. of Greenview No. 16 VU40 V VU Woodlands County Whitecourt County of Barrhead No. 11 Thorhild County Smoky Lake Barrhead 32 St. Paul VU County of St. Paul No. 19 Frog Lake VU18 VU2 Redwater Elk Point Mayerthorpe Legal Grande Cache VU36 U38 VU43 V Bon Accord 28A Lac Ste. Anne County Sturgeon County UV 28 Gibbons Bruderheim VU22 Morinville VU Lamont County Edson Riv Eds er on R Lamont iver County of Two Hills No. 21 37 U15 I.D. No. 25 Willmore Wilderness Lac Ste. Anne VU V VU15 VU45 r Onoway e iv 28A S R UV 45 U m V n o o Chip Lake e k g Elk Island National Park of Canada y r R tu i S v e Mundare r r e Edson 22 St. Albert 41 v VU i U31 Spruce Grove VU R V Elk Island National Park of Canada 16A d Wabamun Lake 16A 16A 16A UV o VV 216 e UU UV VU L 17 c Parkland County Stony Plain Vegreville VU M VU14 Yellowhead County Edmonton Beaverhill Lake Strathcona County County of Vermilion River VU60 9 16 Vermilion VU Hinton County of Minburn No. 27 VU47 Tofield E r i Devon Beaumont Lloydminster t h 19 21 VU R VU i r v 16 e e U V r v i R y Calmar k o Leduc Beaver County m S Leduc County Drayton Valley VU40 VU39 R o c k y 17 Brazeau County U R V i Viking v e 2A r VU 40 VU Millet VU26 Pigeon Lake Camrose 13A 13 UV M U13 VU i V e 13A tt V e Elk River U R County of Wetaskiwin No. -

Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta Community Profiles

For additional copies of the Community Profiles, please contact: Indigenous Relations First Nations and Metis Relations 10155 – 102 Street NW Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4G8 Phone: 780-644-4989 Fax: 780-415-9548 Website: www.indigenous.alberta.ca To call toll-free from anywhere in Alberta, dial 310-0000. To request that an organization be added or deleted or to update information, please fill out the Guide Update Form included in the publication and send it to Indigenous Relations. You may also complete and submit this form online. Go to www.indigenous.alberta.ca and look under Resources for the correct link. This publication is also available online as a PDF document at www.indigenous.alberta.ca. The Resources section of the website also provides links to the other Ministry publications. ISBN 978-0-7785-9870-7 PRINT ISBN 978-0-7785-9871-8 WEB ISSN 1925-5195 PRINT ISSN 1925-5209 WEB Introductory Note The Metis Settlements and First Nations in Alberta: Community Profiles provide a general overview of the eight Metis Settlements and 48 First Nations in Alberta. Included is information on population, land base, location and community contacts as well as Quick Facts on Metis Settlements and First Nations. The Community Profiles are compiled and published by the Ministry of Indigenous Relations to enhance awareness and strengthen relationships with Indigenous people and their communities. Readers who are interested in learning more about a specific community are encouraged to contact the community directly for more detailed information. Many communities have websites that provide relevant historical information and other background. -

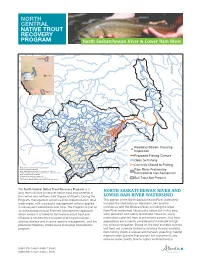

North Central Native Trout Recovery Program : North Saskatchewan

NORTH CENTRAL NATIVE TROUT RECOVERY PROGRAM North Saskatchewan River & Lower Ram River Edmonton N o ³ North r t Saskatchewan Red Deer h Sa River ska tc Study Area h e w a n R i v e r Calgary B ig B ea ve r C reek Ca H ny a Sh on ve un C n da re C Cr ek re ee e k Su k n se ek k D t Cre C e ee r p re e e Gon C st C r ik e Bu a re k h C C e ree k ic y k k a e ek n k re C C n ut r u ro e S T Bighorn R e ive G k k r k a k ee e e r p re e C C r C ine !. k und C c re L o e n J r E k o a P s C h K eR y e oyc i h k l J v u ee o t e i Ro gh Cr Bull Creek i r w t dd li C i C p reek ek L r e r C e C C e a r in k r e ad e e Taw e K iska Creek k k Nort k h Ram e Riv e er r !. C k !.!. o t e e !. n i r C P l O l !. tt a e F !. r C Abraham r ee !. Lake k !. !. !. !. Lynx C !. Roadway Stream Crossing nion C reek O reek Inspection k !.