Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Type, Figured and Cited Specimens in the Museum of Isle of Wight Geology (Isle of Wight, England)

THE GEOLOGICAL CURATOR VOLUME 6, No.5 CONTENTS PAPERS TYPE, FIGURED AND CITED SPECIMENS IN THE MUSEUM OF ISLE OF WIGHT GEOLOGY (ISLE OF WIGHT, ENGLAND). by J.D. Radley ........................................ ....................................................................................................................... 187 THE WORTHEN COLLECTION OF PALAEOZOIC VERTEBRATES AT THE ILLINOIS STATE MUSEUM by R.L. Leary and S. Turner ......................... ........................................................................................................195 LOST AND FOUND ......................................................................................................................................................207 DOOK REVIEWS ........................................................................................ ................................................................. 209 GEOLOGICAL CURATORS' GROUP .21ST ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING .................................................213 GEOLOGICAL CURATORS' GROUP -April 1996 TYPE, FIGURED AND CITED SPECIMENS IN THE MUSEUM OF ISLE OF WIGHT GEOLOGY (ISLE OF WIGHT, ENGLAND) by Jonathan D. Radley Radley, J.D. 1996. Type. Figured and Cited Specimens in the Museum of Isle of Wight Geology (Isle of Wight, England). The Geological Curator 6(5): 187-193. Type, figured and cited specimens in the Museum of Isle of Wight Geology are listed, as aconseouence of arecent collection survev and subseauentdocumentation work. Strengths.. currently lie in Palaeogene gas tropods, and Lower -

The Stratigraphical Framework for the Palaeogene Successions of the London Basin, UK

The stratigraphical framework for the Palaeogene successions of the London Basin, UK Open Report OR/12/004 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OPEN REPORT OR/12/004 The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used The stratigraphical framework for with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. the Palaeogene successions of the Licence No: 100017897/2012. London Basin, UK Key words Stratigraphy; Palaeogene; southern England; London Basin; Montrose Group; Lambeth Group; Thames Group; D T Aldiss Bracklesham Group. Front cover Borehole core from Borehole 404T, Jubilee Line Extension, showing pedogenically altered clays of the Lower Mottled Clay of the Reading Formation and glauconitic sands of the Upnor Formation. The white bands are calcrete, which form hard bands in this part of the Lambeth Group (Section 3.2.2.2 of this report) BGS image P581688 Bibliographical reference ALDISS, D T. 2012. The stratigraphical framework for the Palaeogene successions of the London Basin, UK. British Geological Survey Open Report, OR/12/004. 94pp. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. Maps and diagrams in this book use topography based on Ordnance Survey mapping. © NERC 2012. -

Policy and Practice for the Protection Of

POLICY AND PRACTICE FOR THE PROTECTION OF GROUNDWATER SOUTHERN REGION APPENDIX W R A YtO @ 0^ ? CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Description of Southern Region 3. Office Locations and Administration 4. The Importance of Groundwater 1n Southern Region 5. Rainfall and Recharge 6. Geology and Hydrogeology 7. Use of National Policy with old Southern Region Maps until new maps and zones are produced 8. Cone1us1on/Summary Tables Table 1 Geological Succession 1n Southern Region Table 2 Classification of Strata 1n Southern Region Table 3 Correlation between old Southern Water Aquifer Protection Zone and new National Policy Protection Zones Figure 1 D1agrammat1c Comparison of old and new source protection zones Maps Map 1 Southern Region Area Map 2 Distribution of Rainfall and Public Water Supply Sources Map 3 Water Company Boundaries 1. INTRODUCTION Purpose of the Regional Appendix Th 1 s Reg1ona 1 Appendi x to the NRA " Pol 1 cy and Pract 1 ce for the Protection of Groundwater" provides Information specific to Southern Region. Details are given on the following subjects: * Description of Southern Region * Geology and Hydrogeology * Main Office Locations and Contacts relevant to groundwater matters * How to use the "Policy and Practice for the Protection of Groundwater" prior to the Introduction of new maps and protection zones Th1 s 1 s one of ten appendices that have been produced, each one specific to a different NRA region. Although the main document 1s a national one there are certain considerations, within the headings listed above, that are only relevant to this Region. Each appendix 1s produced to the same format with the necessary extra Information included. -

35. the "UPPER EOCENE, C.Om.P~'F/N~ T~F BARTON

Downloaded from http://jgslegacy.lyellcollection.org/ at University of California-San Diego on July 6, 2016 ~7~ MESSRS.GARDNER~ KEEPING, AND NONCKTON ON THE 35. The "UPPER EOCENE, C.om.p~'~F/n~ t~f BARTON ~nd UPPER BAGSHOT Fox,Ions. By J. S~ARXIE GARDSmZ, Esq., F.G.S., F.L.S., HE,mr KE~P~a, Esq., and H. W. MercaTor, Esq., F.G.S. (Read March 28, 1888.) THE introduction of the Oligocene stage into our classification has necessitated a partial revision of the grouping of our older British Tertiaries. Whether this introduction of a new primary division into the Tertiary system was necessary or expedient may still be ques- tioned ; but it has been generally adopted and is, for the time being, established. The division does not coincide in England with a marked change in either fauna or flora, though the series seems nevertheless tolerably complete and well developed; its limits, however widely stretched~ show that the Oligocene stage compares neither with the Eocene nor the Miocene in importance. Opinions have differed as to where the line of division should be drawn; whether this should be as low down as the top of the Barton Beds or at the base of the Headou Beds, or even higher. For our part, we think it desirable to uphold the view which places the demarcation between the top of the Bagshot Sands of Alum Bay and the base of the Lower Headon Series, though it is perfectly ob- vious that any such line in the midst of our series must be a purely artificial one. -

A Review of the Decapod Crustaceans from the Tertiary of the Isle of Wight, Hampshire, U

Bulletin of the Mizunami Fossil Museum, no. 38 (2012), p. 33–51, 4 pls., 2 figs., 2 tables. 33 © 202, Mizunami Fossil Museum A review of the decapod crustaceans from the Tertiary of the Isle of Wight, Hampshire, U. K, with description of three new species W. J. Quayle* and J. S. H. Collins** * 4, Argyll Street, Ryde, Isle of Wight, Hampsire, England<[email protected]> ** 8, Shaws Cottages, Perry Rise, London, SE23 2QN, and The Natural History Museum, London, SW7 5BD, England Abstract To the known decapod crustaceans of the Tertiary deposits of the Isle of Wight, Hampshire, the Early Eocene species, Basinotopus lamarkii (Desmarest) and Dromilites bucklandi Bell are introduced from the mainland, as are Glyphithyreus wetherelli (Bell), Rhachiosoma bispinosum Woodward, Coeloma (Litoricola) dentate (Woodward), Xanthilites bowerbanki Bell, and Xanthopsis unispinosa (M'Coy), the stratigrahic range of which has been extended to the London Clay on the Island. The development of an anomaly concerning Zanthopsis unispinosa, also present, if not peculiar to the island, is well established. A carapace of Harpactocarcinus sp. from this horizon is the first British record for the genus. Late Eocene species new to the island are Goniocypoda quaylei Crane, Orthakrolophus depressus? (Quayle and Collins) and Typilobus belli Quayle and Collins. Three new genera and species are described from the Late Eocene Headon Hill Formation; a callianassid, Vecticallichirus abditus; a goneplacid, Gonioplacoides minuta, and a hexapodid, Headonipus tuberculosus. New, superior material of the Late Eocene species, Typilobus obscurus Quayle and Collins, from the type locality, Colwell Bay necessitates a new description. A table of all known Tertiary species of decapod crustaceans from the Isle of Wight is appended. -

Barton-On-Sea Instability

Barton-on-Sea Instability Peter Ferguson NFDC Introduction •Geological setting •Engineering works •Ground movement & instability •Public safety & engagement •Management & maintenance •Monitoring •Ground investigations •Future schemes •Funding Location © Crown copyright and database rights 2014 Ordnance Survey 100026220 Geology Geology Geology Geology • Geology of Hampshire & Isle of Wight After Woodward 1904 Ian West 2000 Geology • Stratigraphy Plateau Gravel Bed L Pleistocene (fluvial deposits) Bed K Bed J Eocene Strata (Barton Sand Formation) Bed I Geology • Internationally important exposure • English Nature • Maintain exposures • SSSI rating • Unique exposure of Barton Beds Geology Geology Geology Translational Slides Engineering Works • 1930 – First Defences • Timber groynes & cliff drainage • 1939 to 1945 – Disrepair • 1950 Works become ineffective • Erosion rate 1-2m year • 1964 – 1968 Major works undertaken • Vertical piled revetment • Re-profiled slope • Sheet pile cut off wall • 1970’s • 5 rock groynes • 1990’s • Timber revetment replaced with rock revetment Engineering Works Ground Movement & Instability N • Landslide data Naish Barton-on-Sea Continuing mass movement 200m Ground Movement & Instability Cliff House Hotel Naish Farm Marine Drive W Barton Court Marine Drive E Ground Movement & Instability •Cliff House Hotel •Deep -seated failure • Occurred early 2001 • Displaced rock revetment at toe Cliff House Hotel Hosseyni et al. (In Press) Barton & Garvey (2011) Translational failure with mudslides Shear on base of D and possibly -

Natural Environment Research Council British Geological Survey Geology of the Poole-Bournemouth Area Part of 1:50 000 Sheet 329 (Bournemouth) C.R

Natural Environment Research Council British Geological Survey Geology of the Poole-Bournemouth area Part of 1:50 000 Sheet 329 (Bournemouth) C.R. Bristow and E.C. Freshney with'an account of the hydrogeology by R.A.Monkhouse Palaeontological contributions by R.Harland, M.J.Hughes, D.K.Graham and C.J.Wood / Bibliographical r~f~sence BRISTOW, C.R. and FRESRNEY, E.C. 1986 Geology of the Poole-Bournemouth area Geological report for DOE: Land Use Planning (Exeter: British Geological Survey) Authors C.R.Bristow, Ph.D and E.C. Freshney, Ph.D. British Geological Survey St Just, 30 Pennsylvania Road Exeter EX4 6BX Production of this report was funded by the Department of the Environment The views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department of the Environment c Crown Copyright 1986 EXETER: BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CORRECTION Owing to error in pagination this report contains no page 30 This report has been generated from a scanned image of the document with any blank pages removed at the scanning stage. Please be aware that the pagination and scales of diagrams or maps in the resulting report may not appear as in the original POOLE-BOURNEMOUTH EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report summarises the results of the three phases of a three year project to investigate the geology of the Poole Bournemouth area in Dorset, funded by the Department of the Environment. frior to the commencement of the project, no adequate 1:10,000 scale geological maps of the Poole-Bourne mouth area were available. The district has important sand resources, currently being extensively quarried on Canford heath, Beacon Hill and Henbury. -

1000971.Doc (Converted)

File ref: County: Hampshire/Dorset Site Name: Highcliffe to Milford Cliffs SSSI Status: Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) notified under Section 28 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act, 1981 Local Planning Authority: Hampshire County Council/Dorset County Council, New Forest District Council/Christchurch Borough Council National Grid Reference: SZ 240928 Ordnance Survey Sheet 1:50,000: 195 1:10,000: SZ 19 SE, SZ 29 SE, SW Area: 110.8 (ha) 273.7 (ac) Date Notified (Under 1949 Act): 1953 Date of Last Revision: – Date Notified (Under 1981 Act): 21 March 1991 Date of Last Revision: – Confirmed: 10 December 1991 Other Information: Site extended westwards to Friars Cliff. Reasons for Notification: The Highcliffe to Milford Cliffs Site of Special Scientific Interest extends for some nine kilometres along the cliffs at Christchurch Bay. Its entire length comprises steep coastal slopes and cliffs which are locally dissected by deeply incised ‘bunnies’ or ravines. This coastal site provides access to the standard succession of the fossil rich Barton Beds and Headon Beds. Various exposures within the Site are considered important both in a national and international context. The principal features of interest are described below. The oldest rocks are described first. These rocks lie in the western part of the site, younger rocks being found progressing eastward. Friars Cliff, Dorset, is a key Tertiary Site providing an opportunity to study the marginal marine sediments deposited during the terminal regressive phase of the Auversian (Upper Bracklesham) and the earliest, marine transgression phase of the Bartonian. The section provides a unique exposure of distributary mouth-bar sequences in the uppermost Bracklesham Beds, and, together with sections in Poole Bay, enable a good reconstruction of an ancient estuary to be made. -

Barton-On-Sea and Highcliffe the Shells Are Quite Exquisite and Often Resemble Is Highly Fossiliferous and the Sandy Beach Here Modern Tropical Shells

BARTON - ON - SEA HAMPSHIRE INTRODUCTION TO BARTON ON SEA THE GEOLOGY Thank you for enrolling on our fossil hunting event. The Barton Beds are totally representative of a marine environment. The clays were deposited at the bottom of The fast- eroding coastline at Barton on Sea a warm, marginal sea shelf, close to land during the provides a fantastic location for collecting fossils Eocene epoch. from the Barton Beds, which are comprised of Eocene clays and sands of approximately 40 million years in age. The Barton Clay here is about 30 metres thick and overlain by the Chama Sands and Becton Sand. The The site is famed for its fossils of more than 600 changes in sea level are clearly seen and represented different types of shells, which represent a time by various layers found within the Barton Clay. There when Briain was bathed in a climate not are 10 beds in total, indicating shallow, near-shore and dissimilar to modern Spain. Other common deeper off-shore conditions. The presence of wood and fossils include shark an ray teeth, turtle bones plant material indicates the nearby land during and carapace and fish remains. deposition. The cliffs between Barton-on-Sea and Highcliffe The shells are quite exquisite and often resemble is highly fossiliferous and the sandy beach here modern tropical shells. Their preparation requires no makes it an ideal location for children. Climbing more than gentle brushing and a coating of a dilute the crumbling cliffs is not recommended but at solution of PVA: water at a rate of 1:3, which will beach level (and even among the tourist sunbathers!) the low clay cliffs and slippages preserve the shell for years to come. -

From the Eocene Barton Clay Formation of the Hampshire Basin

Bulletin of the Mizunami Fossil Museum, no. 42 (2016), p. 29–37, 3 fi gs., 1plate. © 2016, Mizunami Fossil Museum A new fossil record of a tanaidacean (Crustacea, Peracarida), from the Eocene Barton Clay Formation of the Hampshire Basin W. J. Quayle 4, Argyll Street, Ryde, Isle of Wight, Hampshire, England <[email protected]> Abstract A new fossil of a tanaid from the Eocene Barton Clay Formation of the Hampshire Basin is described. At the present time fossil tanaids are known from the Carboniferous up to, and including the Cretaceous. The new species, Barapseudia prima gen. et sp. nov., from the Eocene will fill a hiatus from the Eocene, extending to the Recent, in our knowledge of the Tanaidae. Burrows which could be associated with tanaids were found in the same deposit. Key words: Peracarida, tanaidaceans, burrows, Eocene, Barton Clays, England. Introduction to the reconstruction of the figures. Ophtalmapseudes rhenanus (Malzahn, 1957), from the Permian, was reassigned to the suborder The Barton Beds of Christchurch Bay, Hampshire, have Anthracocaridomorpha Sieg, 1980; Opthalmapseudes sp. long been known for their rich fossil fauna, though very few (Vegh and Bachmayer, 1965) from the Triassic, was described crustaceans are known. Woodward (1867) described a crab, as a non descript chela. The holotype of Palaeotanais Goniocypoda edwardsi, from the Lower Eocene of Christchurch quenstedti (Rieff, 1936), could not be found and until new Bay; Burton (1933, p. 162) drew attention to the presence of material can be obtained, interpretation is from the literature. chelae of Calappa sp.= (Calappilia) and of a xanthoid crab Ophthalmapseudes friedericianus Malzahn, 1965 and O. -

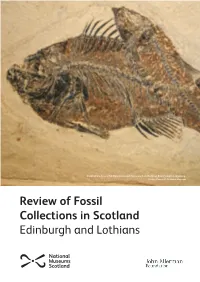

Review of Fossil Collections in Scotland Edinburgh and Lothians Edinburgh and Lothians

Detail of the Eocene fishDiplomystus and Priscacara from the Green River Formation, Wyoming. Yvonne Cooper © Cockburn Museum Review of Fossil Collections in Scotland Edinburgh and Lothians Edinburgh and Lothians Haddington Museum Headquarters (East Lothian Council Museums Service) Almond Valley Heritage Centre (Almond Valley Heritage Trust) Cockburn Museum (University of Edinburgh Collections) Anatomical Museum (University of Edinburgh Collections) Natural History Collections (University of Edinburgh Collections) 1 Haddington Museum Headquarters (East Lothian Council Museums Service) Collection type: Local Authority 41 Dunbar Road, Haddington, East Lothian, EH41 3PJ Contact: [email protected] Location of collections The Libraries and Museums Headquarters houses East Lothian Council’s stored collections. Areas to display objects from the collections are available at the John Gray Centre Museum, Haddington. Size of collections 35-40 fossils. Onsite records Information is recorded in a Modes CMS with entry forms for most items. Collection highlights 1. Material from the Lothian Carboniferous shrimp beds, linked to Euan Clarkson. Published information Briggs, D.E.G., N.D.L. Clark, and E.N.K. Clarkson. (1991). The Granton ‘shrimp-bed’, Edinburgh — a Lower Carboniferous Konservat-Lagerstätte. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of The Royal Society of Edinburgh. 82:65-85. Collection overview Fossils are in numbered boxes with other geological specimens. They include corals, brachiopods (Eomarginifera, productids and fossils labelled as Atrypa but probably a type of orthid brachiopod), bivalves (Edmondia and modern oyster), orthoconic nautiloids, gastropods (Straparollus), crinoids (usually disarticulated in limestone) and ‘macaroni rock’ (densely packed with coral, perhaps of the Carboniferous coral Syringopora from Barns Ness, Dunbar), most of which are Carboniferous. -

Hants Field Club 1890 Clays of Hampshire Figs: 1-6

HANTS FIELD CLUB 1890 CLAYS OF HAMPSHIRE WILSON LITHO FIGS: 1-6 SULPHATE OF LIME, CRYSTALS fll*FIG D7 wriMCCONCRETION rtC AVDDI OF IMCLAY IRONSTONE 23 THE CLAYS OF HAMPSHIRE AND THEIR ECONOMIC USES. BY T. W. SHORE, F.G.S., F.C.S. Hampshire probably contains a greater variety of clays of different geological ages than any other English county. This arises mainly from the circumstance that it contains a greater- variety of Tertiary beds than exists elsewhere in England. These Tertiary clays exhibit important differences, although some of them have points of resemblance. The Hampshire clays are not, however, confined to those of the Tertiary age, for the oldest that are found in this county and used for economic purposes are the Wealden shales, and the most recent are the deposits of clay alluvium which lie near the wide mouths of the estuaries or along the banks of the rivers. The relative ages of these clays may be seen from the geological table which is given herewith, and which shows the sequence of beds as they occur in Hampshire, those beds from which clay is obtained for economic purposes being marked with an asterisk (*). From this table it will be seen that clay is or has been worked in this county from deposits of more than twelve different geological periods. The Tertiary clays lie both in the north and south of the county with a broad extent of chalk between, separating the Hampshire basin-from that part of the London basin which is included in the northern part of this county.