World Set Free

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Making of an Atomic Bomb

(Image: Courtesy of United States Government, public domain.) INTRODUCTORY ESSAY "DESTROYER OF WORLDS": THE MAKING OF AN ATOMIC BOMB At 5:29 a.m. (MST), the world’s first atomic bomb detonated in the New Mexican desert, releasing a level of destructive power unknown in the existence of humanity. Emitting as much energy as 21,000 tons of TNT and creating a fireball that measured roughly 2,000 feet in diameter, the first successful test of an atomic bomb, known as the Trinity Test, forever changed the history of the world. The road to Trinity may have begun before the start of World War II, but the war brought the creation of atomic weaponry to fruition. The harnessing of atomic energy may have come as a result of World War II, but it also helped bring the conflict to an end. How did humanity come to construct and wield such a devastating weapon? 1 | THE MANHATTAN PROJECT Models of Fat Man and Little Boy on display at the Bradbury Science Museum. (Image: Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory.) WE WAITED UNTIL THE BLAST HAD PASSED, WALKED OUT OF THE SHELTER AND THEN IT WAS ENTIRELY SOLEMN. WE KNEW THE WORLD WOULD NOT BE THE SAME. A FEW PEOPLE LAUGHED, A FEW PEOPLE CRIED. MOST PEOPLE WERE SILENT. J. ROBERT OPPENHEIMER EARLY NUCLEAR RESEARCH GERMAN DISCOVERY OF FISSION Achieving the monumental goal of splitting the nucleus The 1930s saw further development in the field. Hungarian- of an atom, known as nuclear fission, came through the German physicist Leo Szilard conceived the possibility of self- development of scientific discoveries that stretched over several sustaining nuclear fission reactions, or a nuclear chain reaction, centuries. -

The Online Version of Catalogue 32 Does Not Contain the Printed

Please note: The online version of Catalogue 32 does not contain the printed version’s 172 black and white illustrations—this is because the illustrations in the printed catalogue were submitted to the printer as hard copy, rather than electronic files. Future catalogues will have digitized illustrations, so that their online versions will be exact counterparts of the printed ones. Catalogue 32 CLASSICS OF SCIENCE & MEDICINE With 172 black & white and 6 color illustrations Table of Contents Science & Medicine Page 5 Recent Books, History & Reference 80 Norman Publishing 83 About Our Cover. The cover of Catalogue 32 features the following: (1) No. 198, a beautifully executed bronze bust of Ambroise Paré by the 19th century French sculptor Emile Picault (ca. 1893); (2) No. 109, Domenico Fontana’s Della transportatione dell’obelisco (1590), a classic of Renaissance engineering describing the removal of the Vatican obelisk to its present site in the Piazza of St. Peter; (3) No. 127, George Robert Gray’s Genera of Birds (1849), with magniWcent plates by David William Mitchell, Joseph Wolf, Edward Lear and others; (4) On the Fabric of the Human Body (1998), the English translation of the Wrst book of Andreas 1543 1 4 Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica ( ); 5 (5) No. 112, Narrative of a Journey to the Shores of the Polar Sea (1823), John Franklin’s clas- 23 sic account of his Wrst Arctic expedition of 1819–22; (6) No. 103, Oliver Byrne’s edition of The First Six Books of the Elements of Euclid 6 (1847), one of the most striking and attrac- tive examples of color printing issued by the noted Victorian publisher William Pickering; and (7) No. -

Fizzling the Plutonium Economy: Origins of the April 1977 Carter Administration Fuel Cycle Policy Transition

Fizzling the Plutonium Economy: Origins of the April 1977 Carter Administration Fuel Cycle Policy Transition The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Williams, Peter King. 2010. Fizzling the Plutonium Economy: Origins of the April 1977 Carter Administration Fuel Cycle Policy Transition. Master's thesis, Harvard University, Extension School. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37367548 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Fizzling the Plutonium Economy: Origins of the April 1977 Carter Administration Fuel Cycle Policy Transition Peter Williams A Thesis in the Field of History for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2010 © 2010 Peter Williams Abstract This study examines the scientific advocacy that shaped President Carter’s April 1977 policy decision to block the domestic implementation of so-called “plutonium economy” technologies, and thereby mandate the use of an “open” or “once–through” fuel cycle for U.S. nuclear power reactors. This policy transition was controversial, causing friction with U.S. allies, with the nuclear power industry, and with Congress. Early in his presidential campaign, Carter criticized the excessive federal financial commitment to developing plutonium-based reactors and adopted the view that the weapons proliferation risks of plutonium economy technologies were serious and needed to be addressed. -

2018 Real-Time Conference June 11Th-15Th, 2018, Williamsburg, Virginia, USA

NPSS News ISSUEISSUE 1: MARCH1 : MAY 22O13O18 A PUBLICATION OF THE INSTITUTE OF ELECTRICAL & ELECTRONICS ENGINEERS The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Colonial The 2018 Real-Time Conference June 11th-15th, 2018, Williamsburg, Virginia, USA CONFERENCES and trigger systems to control and monitoring, real- Located in southeastern Virginia (on the mid-Atlantic Real-Time 1 time safety/security, processing, networks, upgrades, coast of the U.S.), the town of Williamsburg is part NSREC 2 new standards and emerging technologies. of what is known as the Historical Triangle (including IPAC 2 Jamestown and Yorktown). It is an area of significant The Real-Time Conference has historically been importance to early English colonial history and the SOCIETY GENERAL BUSINESS a relatively small conference (typically 200-250 birth of the United States. The conference venue, President’s Report 3 participants). We are able to create a scientific Woodlands Hotel and Conference Center, is part Secretary’s Report 4 program that consists only of plenary oral sessions of Colonial Williamsburg, a living-history recreation New AdCom Officers and Members 5 and dedicated poster sessions for all attendees. In of the first capitol of the Virginia Colony (circa mid- David Abbott, addition, poster presenters are given the opportunity 1700s). The area is a popular vacation destination TECHNICAL COMMITTEES General Chair; Williamsburg to give a short (two-minute) overview of their paper with many historical landmarks and museums as CANPS 6 so that participants will have a better understanding well as beaches and large amusement parks. The Radiation Effects 6 The 21st edition of the IEEE-NPSS Real-Time of which posters they may wish to investigate further. -

VC 1978 1 5.Pdf

Under Contract with the U.S. Department of Energy Vol. No. 1 January 5, 1978 CHRISTMAS BIRD COUNT RESULTS About 9,150 birds of 60 species were spotted in the second annual Fermilab Christmas bird count. The count was conducted Saturday, Dec. 17, by the DuPage Audubon Society. Held in con junction with the national Audubon Society's 78th annual census nationwide, the local tally enlisted 43 volunteer observers, including two Fermilab people. They were: David Carey, Com- puting Department and Hannu Miettinen, Theory . b' d ... Ferm~ ~r -counters were L-R: J. Kumb, Department. R. Johnson, R. Hoger, D. Carey, B. Foster ... Starting at 4 a.m., observers logged 78 hours of bird-counting time. The birders were divided into 11 parties of 4 to 6 persons each; five persons monitored bird feeders during the count. Fermilab was the focal point of the count area: a circle with a radius of seven and one-half miles as far north as Wayne; south to Aurora; east to Winfield; and west to the Fox River Valley. Party-hours comprised 54 on foot, 24 by car and 22 at feeders. Of 425.5 party-miles covered, 367 were by auto and 58.5 on foot. Richard Hoger, staff assistant in the supply division at Argonne National Laboratory, coordinated the count activities. Paul Mooring was the compiler. The Fermilab area was among five Chicago areas where counts were made, Mooring said. Nationally, counters were at work from Dec. 17 to Jan. 2 on one-day counts. Observers were assigned to eight sub-areas in the Laboratory count circle. -

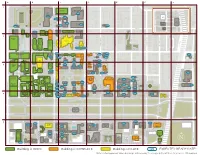

Building Is OPEN Building Is COMPLETE Building Is IN-USE

A B C D E F G E 55TH ST E 55TH ST 1 Campus North Parking Campus North Residential Commons E 52ND ST The Frank and Laura Baker Dining Commons Ratner Stagg Field Athletics Center 5501-25 Ellis Offices - TBD - - TBD - Park Lake S AUG 15 S HARPER AVE Court Cochrane-Woods AUG 15 Art Center Theatre AVE S BLACKSTONE Harper 1452 E. 53rd Court AUG 15 Henry Crown Polsky Ex. Smart Field House - TBD - Alumni Stagg Field Young AUG 15 Museum House - TBD - AUG 15 Building Memorial E 53RD ST E 56TH ST E 56TH ST 1463 E. 53rd Polsky Ex. 5601 S. High Bay West Campus Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Cottage (2021) Utility Plant AUG 15 Michelson High (West) Energy (Central) (East) 55th, 56th, 57th St Grove Center for Metra Station Physics Physics Child Development TAAC 2 Center - Drexel Accelerator Building Medical Campus Parking B Knapp Knapp Medical Regenstein Library Center for Research William Eckhardt Biomedical Building AVE S KENWOOD Donnelley Research Mansueto Discovery Library Bartlett BSLC Center Commons S Lake Park S MARYLAND AVE S MARYLAND S DREXEL BLVD AVE S DORCHESTER AVE S BLACKSTONE S KIMBARK AVE S UNIVERSITY AVE AVE S WOODLAWN S ELLIS AVE Bixler Park Pritzker Need two weeks to transition School of Biopsychological Medicine Research Building E 57TH ST E 57TH ST - TBD - Rohr Chabad Neubauer Collegium- TBD - Center for Care and Discovery Gordon Center for Kersten Anatomy Center - TBD - Integrative Science Physics Hitchcock Hall Cobb Zoology Hutchinson Quadrangle - TBD - Gate Club Institute of- PoliticsTBD - Snell -

Edward Mills Purcell (1912–1997)

ARTICLE-IN-A-BOX Edward Mills Purcell (1912–1997) Edward Purcell grew up in a small town in the state of Illinois, USA. The telephone equipment which his father worked with professionally was an early inspiration. His first degree was thus in electrical engineering, from Purdue University in 1933. But it was in this period that he realized his true calling – physics. After a year in Germany – almost mandatory then for a young American interested in physics! – he enrolled in Harvard for a physics degree. His thesis quickly led to working on the Harvard cyclotron, building a feedback system to keep the radio frequency tuned to the right value for maximum acceleration. The story of how the Manhattan project brought together many of the best physicists to build the atom bomb has been told many times. Not so well-known but equally fascinating is the story of radar, first in Britain and then in the US. The MIT radiation laboratory was charged with developing better and better radar for use against enemy aircraft, which meant going to shorter and shorter wavelengths and detecting progressively weaker signals. This seems to have been a crucial formative period in Purcell’s life. His coauthors on the magnetic resonance paper, Torrey and Pound, were both from this lab. I I Rabi, the physicist who won the 1944 Nobel Prize for measuring nuclear magnetic moments by resonance methods in molecular beams, was the head of the lab and a major influence on Purcell. Interestingly, Felix Bloch (see article on p.956 in this issue) was at the nearby Radio Research lab but it appears that the two did not interact much. -

Chicago Pile-1 - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Chicago Pile-1 - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Chicago Pile-1 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates : 41°47′32″N 87°36′3″W Main page Contents Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1) was the world's first nuclear Site of the First Self Sustaining Nuclear Featured content reactor to achieve criticality. Its construction was part of Reaction Current events the Manhattan Project, the Allied effort to create atomic U.S. National Register of Historic Places Random article bombs during World War II. It was built by the U.S. National Historic Landmark Donate to Wikipedia Manhattan Project's Metallurgical Laboratory at the Wikipedia store Chicago Landmark University of Chicago , under the west viewing stands of Interaction the original Stagg Field . The first man-made self- Help sustaining nuclear chain reaction was initiated in CP-1 About Wikipedia on 2 December 1942, under the supervision of Enrico Community portal Recent changes Fermi, who described the apparatus as "a crude pile of [4] Contact page black bricks and wooden timbers". Tools The reactor was assembled in November 1942, by a team What links here that included Fermi, Leo Szilard , discoverer of the chain Related changes reaction, and Herbert L. Anderson, Walter Zinn, Martin Upload file D. Whitaker, and George Weil . It contained 45,000 Drawing of the reactor Special pages graphite blocks weighing 400 short tons (360 t) used as Permanent link a neutron moderator , and was fueled by 6 short tons Page information Wikidata item (5.4 t) of uranium metal and 50 short tons (45 t) of Cite this page uranium oxide. -

![I. I. Rabi Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Tue Apr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8589/i-i-rabi-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-rendered-tue-apr-428589.webp)

I. I. Rabi Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered Tue Apr

I. I. Rabi Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 1992 Revised 2010 March Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms998009 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm89076467 Prepared by Joseph Sullivan with the assistance of Kathleen A. Kelly and John R. Monagle Collection Summary Title: I. I. Rabi Papers Span Dates: 1899-1989 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1945-1968) ID No.: MSS76467 Creator: Rabi, I. I. (Isador Isaac), 1898- Extent: 41,500 items ; 105 cartons plus 1 oversize plus 4 classified ; 42 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Physicist and educator. The collection documents Rabi's research in physics, particularly in the fields of radar and nuclear energy, leading to the development of lasers, atomic clocks, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and to his 1944 Nobel Prize in physics; his work as a consultant to the atomic bomb project at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory and as an advisor on science policy to the United States government, the United Nations, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization during and after World War II; and his studies, research, and professorships in physics chiefly at Columbia University and also at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. -

Leo Szilard in Physics and Information By

Leo Szilard in Physics and Information by Richard L. Garwin IBM Fellow Emeritus IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Center P.O. Box 218, Yorktown Heights, NY 10598 www.fas.org/RLG/ Email: [email protected] Presented in the invited APS session R17 “The Many Worlds of Leo Szilard” Savannah, Georgia April 7, 2014 at 11:21 AM _04/07/2014 Leo Szilard in Physics and Information.doc 1 Abstract: The excellent biography1 by William Lanouette, ``Genius in the Shadows,'' tells it the way it was, incredible though it may seem. The 1972 ``Collected Works of Leo Szilard: Scientific Papers,'' Bernard T. Feld and Gertrud W. Szilard, Editors, gives the source material both published and unpublished. Szilard's path-breaking but initially little-noticed 1929 paper, ``On the Decrease of Entropy in a Thermodynamic System by the Intervention of Intelligent Beings'' spawned much subsequent research. It connected what we now call a bit of information with a quantity k ln 2 of entropy, and showed that the process of acquiring, exploiting, and resetting this information in a one-molecule engine must dissipate at least kT ln 2 of energy at temperature T. His 1925 paper, ``On the Extension of Phenomenological Thermodynamics to Fluctuation Phenomena,'' showed that fluctuations were consistent with and predicted from equilibrium thermodynamics and did not depend on atomistic theories. His work on physics and technology, demonstrated an astonishing range of interest, ingenuity, foresight, and practical sense. I illustrate this with several of his fundamental contributions to nuclear physics, to the neutron chain reaction and to nuclear reactors, and also to electromagnetic pumping of liquid metals. -

Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science

Nuclear Science—A Guide to the Nuclear Science Wall Chart ©2018 Contemporary Physics Education Project (CPEP) Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science Many Nobel Prizes have been awarded for nuclear research and instrumentation. The field has spun off: particle physics, nuclear astrophysics, nuclear power reactors, nuclear medicine, and nuclear weapons. Understanding how the nucleus works and applying that knowledge to technology has been one of the most significant accomplishments of twentieth century scientific research. Each prize was awarded for physics unless otherwise noted. Name(s) Discovery Year Henri Becquerel, Pierre Discovered spontaneous radioactivity 1903 Curie, and Marie Curie Ernest Rutherford Work on the disintegration of the elements and 1908 chemistry of radioactive elements (chem) Marie Curie Discovery of radium and polonium 1911 (chem) Frederick Soddy Work on chemistry of radioactive substances 1921 including the origin and nature of radioactive (chem) isotopes Francis Aston Discovery of isotopes in many non-radioactive 1922 elements, also enunciated the whole-number rule of (chem) atomic masses Charles Wilson Development of the cloud chamber for detecting 1927 charged particles Harold Urey Discovery of heavy hydrogen (deuterium) 1934 (chem) Frederic Joliot and Synthesis of several new radioactive elements 1935 Irene Joliot-Curie (chem) James Chadwick Discovery of the neutron 1935 Carl David Anderson Discovery of the positron 1936 Enrico Fermi New radioactive elements produced by neutron 1938 irradiation Ernest Lawrence -

EUGENE PAUL WIGNER November 17, 1902–January 1, 1995

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES E U G ENE PAUL WI G NER 1902—1995 A Biographical Memoir by FR E D E R I C K S E I T Z , E RICH V OG T , A N D AL V I N M. W E I NBER G Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1998 NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS WASHINGTON D.C. Courtesy of Atoms for Peace Awards, Inc. EUGENE PAUL WIGNER November 17, 1902–January 1, 1995 BY FREDERICK SEITZ, ERICH VOGT, AND ALVIN M. WEINBERG UGENE WIGNER WAS A towering leader of modern physics Efor more than half of the twentieth century. While his greatest renown was associated with the introduction of sym- metry theory to quantum physics and chemistry, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for 1963, his scientific work encompassed an astonishing breadth of sci- ence, perhaps unparalleled during his time. In preparing this memoir, we have the impression we are attempting to record the monumental achievements of half a dozen scientists. There is the Wigner who demonstrated that symmetry principles are of great importance in quan- tum mechanics; who pioneered the application of quantum mechanics in the fields of chemical kinetics and the theory of solids; who was the first nuclear engineer; who formu- lated many of the most basic ideas in nuclear physics and nuclear chemistry; who was the prophet of quantum chaos; who served as a mathematician and philosopher of science; and the Wigner who was the supervisor and mentor of more than forty Ph.D.