Chapter 7. from Cooperation to Compassion: Death and Bereavement on Social Networking Websites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

¬タᆰmichael Jackson Mtv Awards 1995 Full

Rafael Ahmed Shared on Google+ · 1 year ago 1080p HD Remastered. Best version on YouTube Reply · 415 Hide replies ramy ninio 1 year ago Il est vraiment très fort Michael Jackson !!! Reply · Angelo Oducado 1 year ago When you make videos like this I recommend you leave the aspect ratio to 4:3 or maybe add effects to the black bars Reply · Yehya Jackson 11 months ago Hello My Friend. Please Upload To Your Youtube Channel Michael Jackson's This Is It Full Movie DVD Version And Dangerous World Tour (Live In Bucharest 1992). Reply · Moonwalker Holly 11 months ago Hello and thanks for sharing this :). I put it into my favs. Every other video that I've found of this performance is really blurry. The quality on this is really good. I love it. Reply · Jarvis Hardy 11 months ago Thank cause everyother 15 mn version is fucked damn mike was a bad motherfucker Reply · 6 Moonwalker Holly 11 months ago +Jarvis Hardy I like him bad. He's my naughty boy ;) Reply · 1 Nathan Peneha A.K.A Thepenjoker 11 months ago DopeSweet as Reply · vaibhav yadav 9 months ago I want to download michael jackson bucharest concert in HD. Please tell the source. Reply · L. Kooll 9 months ago buy it lol, its always better to have the original stuff like me, I have the original bucharest concert in DVD Reply · 1 vaibhav yadav 9 months ago +L. Kooll yes you are right. I should buy one. Reply · 1 L. Kooll 9 months ago +vaibhav yadav :) do it, you will see you wont regret it. -

Song Title Version 1 More Time Daft Punk 5,6,7,8 Steps All 4 L0ve Color Me Badd All F0r Y0u Janet Jackson All That I Need Boyzon

SONG TITLE VERSION 1 MORE TIME DAFT PUNK 5,6,7,8 STEPS ALL 4 L0VE COLOR ME BADD ALL F0R Y0U JANET JACKSON ALL THAT I NEED BOYZONE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ACE OF BASE ALWAYS ERASURE ANOTHER NIGHT REAL MCCOY BABY CAN I HOLD YOU BOYZONE BABY G0T BACK SIR MIX-A-LOT BAILAMOS ENRIQUE IGLESIAS BARBIE GIRL AQUA BLACK CAT JANET JACKSON BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM!! VENGABOYS BOP BOP BABY WESTUFE BRINGIT ALL BACK S CLUB 7 BUMBLE BEE AQUA CAN WE TALK CODE RED CAN'T BE WITH YOU TONIGHT IRENE CANT GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD KYLIE MINOGUE CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE UB40 CARTOON HEROES AQUA C'ESTLAVIE B*WITCHED CHIQUITITA ABBA CLOSE TO HEAVEN COLOR ME BADD CONTROL JANET JACKSON CRAZY FOR YOU MADONNA CREEP RADIOHEAD CRY FOR HELP RICK ASHLEY DANCING QUEEN ABBA DONT CALL ME BABY MADISON AVENUE DONT DISTURB THIS GROOVE THE SYSTEM DONT FOR GETTO REMEMBER BEE GEES DONT LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD SANTA ESMERALDA DONT SAY YOU LOVE ME M2M DONT TURN AROUND ACE OF BASE DONT WANNA LET YOU GO FIVE DYING INSIDE TO HOLDYOU TIMMY THOMAS EL DORADO GOOMBAY DANCE BAND ELECTRIC DREAMS GIORGIO MORODES EVERYDAY I LOVE YOU BOYZONE EVERYTHING M2M EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE FAITHFUL GO WEST FATHER AND SON BOYZONE FILL ME IN CRAIG DAVID FIRST OF MAY BEE GEES FLYING WITHOUT WINGS WESTLIFE FOOL AGAIN WESTLIFE FOR EVER AS ONE VENGABOYS FUNKY TOWN UPS INC GET DOWN TONIGHT KC & THE SUNSHINE BAND GET THE PARTY STARTED PINK GET UP (BEFORE THE NIGHT IS OVER) TECHNOTRONIC GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY SONG BONEY M. -

A Mass of Resurrection in Loving Memory Of

A Mass of Resurrection In Loving Memory Professional Services Entrusted to: Bell Funeral Home of Forestdale, Alabama Frank Phillip “Phil” Slovensky Internment Phillip was buried April 4, 2020 Saint Michael’s Cemetery Brookside, Alabama Pallbearers Phillip was buried April 4, 2020 and his Pallbearers were: Chris Hand Jaimie Hand Jerome Hand John Maxwell Patrick Maxwell Mark Slovensky Jimmy Slovensky Ron Slovensky Ryan Slovensky From the Family We mourn Phil’s passing because we are human and we will miss him dearly, but we rejoice because he lived a life of loving and generous service and he believed in Jesus’ promise of eternal life. We, the family of Frank Phillip Phil Slovensky., wish to extend our sincere gratitude and heartfelt appreciation for the many acts of kindness shown during this special and difficult time. We will remember forever your cards, calls, prayers, and your presence. The Slovensky Family 11:00 AM Saturday, August 8, 2020 Saint Patrick Catholic Church Adamsville, Alabama Very Reverend Vernon F. Huguley Pastor Phil Slovensky In Memory of Our Brother Phillip So much sorrow, with infinite pain, I little knew that morning God was to call my name. The emotions inside, we could never explain. In life I loved you dearly, in death I do the same. Our brother has left, as we stand here and cry. It broke my heart to leave you, I did not go alone. Our burning tears, are asking us why. For part of you went with me. The day God called me home. We'll cherish those memories, we all have shared. -

Songs by Title

Sound Master Entertainment Songs by Title smedenver.com Title Artist Title Artist #thatPower Will.I.Am & Justin Bieber 1994 Jason Aldean (Come On Ride) The Train Quad City DJ's 1999 Prince (Everything I Do) I Do It For Bryan Adams 1st Of Tha Month Bone Thugs-N-Harmony You 2 Become 1 Spice Girls Bryan Adams 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer (Four) 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 2 Step Unk & Timbaland Unk (Get Up I Feel Like Being A) James Brown 2.Oh Golf Boys Sex Machine 21 Guns Green Day (God Must Have Spent) A N Sync 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg Little More Time On You 22 Taylor Swift N Sync 23 Mike Will Made-It & Miley (Hot St) Country Grammar Nelly Cyrus' Wiz Khalifa & Juicy J (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew 23 (Exp) Mike Will Made-It & Miley (I Wanna Take) Forever Peter Cetera & Crystal Cyrus' Wiz Khalifa & Juicy J Tonight Bernard 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago (I've Had) The Time Of My Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes 3 Britney Spears Life Britney Spears (Oh) Pretty Woman Van Halen 3 A.M. Matchbox Twenty (One) #1 Nelly 3 A.M. Eternal KLF (Rock) Superstar Cypress Hill 3 Way (Exp) Lonely Island & Justin (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake KC & The Sunshine Band Timberlake & Lady Gaga Your Booty 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake (She's) Sexy + 17 Stray Cats & Timbaland (There's Gotta Be) More To Stacie Orrico 4 My People Missy Elliott Life 4 Seasons Of Loneliness Boyz II Men (They Long To Be) Close To Carpenters You 5 O'Clock T-Pain Carpenters 5 1 5 0 Dierks Bentley (This Ain't) No Thinkin Thing Trace Adkins 50 Ways To Say Goodbye Train (You Can Still) Rock In Night Ranger 50's 2 Step Disco Break Party Break America 6 Underground Sneaker Pimps (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 6th Avenue Heartache Wallflowers (You Want To) Make A Bon Jovi 7 Prince & The New Power Memory Generation 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 8 Days Of Christmas Destiny's Child Jay-Z & Beyonce 80's Flashback Mix (John Cha Various 1 Thing Amerie Mix)) 1, 2 Step Ciara & Missy Elliott 9 P.M. -

Phil Collins Janet Jackson Paula Abdul Better Midler Paula Abdul

1989 ANOTHER DAY IN PARADISE Phil Collins Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: MISS YOU MUCH Janet Jackson Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: STRAIGHT UP Paula Abdul Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: WIND BENEATH MY WINGS Better Midler Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: COLD HEARTED Paula Abdul Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: RIGHT HERE WAITING Richard Marx Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: LOST IN YOUR EYES Debbie Gibson Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: SHE DRIVES ME CRAZY Fine Young Cannibals Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: WE DIDN ’T START THE FIRE Billy Joel Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: LISTEN TO YOUR HEART Roxette Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: ETERNAL FLAME Bangles Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: BABY DON ’T FORGET MY NUMBER Milli Vanilli Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: 1988 NEED YOU TONIGHT INXS Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: LOOK AWAY Chicago Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: SWEET CHILD O’ MINE Guns N’ Roses Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: NEVER GONNA GIVE YOU UP Rick Astley Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: COULD ’VE BEEN Tiffany Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: GET OUTTA MY DREAMS , GET INTO MY CAR Billy Ocean Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: THE FLAME Cheap Trick Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: MAN IN THE MIRROR Michael Jackson Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: WILD , WILD WEST Escape Club Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: EVERY ROSE HAS ITS THORN Poison Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: KOKOMO Beach Boys Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: DON ’T WORRY , BE HAPPY Bobby McFerrin Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: 1987 LIVIN ’ ON A PRAYER Bon Jovi Chart Run: Top 40: Top 10: #1: -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Parenthood" by Jane Richards It Seems As Though Ron Howard Has the Midas Touch

The Pilot, page 8 "Parenthood" By Jane Richards It seems as though Ron Howard has the Midas touch. The Reel Thing After directing such hit films as "Night Shift" and "Splash", one would expect his star to fade a little. Instead, it's Movie Reviews shining brighter than ever, as seen in his latest effort, "Parenthood". A stellar cast, including such big names as Steve Martin, Rick Moranis, Diane Wiest, Keanu Phantom of the Opera, The Reeves, and Tom Hulce help make Motion Picture" this movie one of the best this year. Although, released in By Casper Jetson early August, it continues to By Dash Riprock Do you want to see a good hold its own at the box office "Rhythm Kation 1814", Janet movie? Do you want to see a and is now being shown at the Jackson movie that will literally scare Mall Cinemas in Shelby. living daylights out of you?? There are several plots, Janet is back...and after Do you want to see one of the shown in vignettes, alternating a three year wait, is it worth best-edited movies of 1989? Do from hilarious to sad to sweet. it? You bet it is. Jackson's you want to see one of the most Martin strives to be the perfect last album, "Control", was a versatile actors of our time? father for his eldest son, while colossal success, and it looks If you answered "yes" to a mate-hungry Wiest tries to as though "Rhythm Nation 1814" any of these questions... don't relate to her moody, sexually- will soon be standing by it's go see "Phantom of the Opera". -

Janet Jackson's Rhythm Nation 1814

“Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814”—Janet Jackson (1989) Added to the National Registry: 2020 Essay by Ayanna Dozier (guest post)* Janet Jackson Revolution Televised: “Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation” “Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814” is a significant piece of Black feminist cultural production that pioneered new modes of using popular music to convey socio-cultural commentary to a larger mainstream audience. Conceptual in form, the album’s impact on youth culture is made possible by Jackson’s attentiveness to the televisual as seen in the album’s music videos and its incorporation of television culture in its sonic arrangement. Whereas Jackson’s contemporaries like Madonna, Prince, and even her brother Michael, adapted to television from radio early in their career, Jackson was one of the first true simultaneous audio/visual artists of the 1980s. What emerges from this practice is an album that without having seen its accompanying videos feels visual and cues images to the imagination upon each listen. “Rhythm Nation 1814” responds to what media historian John B. Thompson writes as the verisimilitude of mediated historicity. Mediated historicity defines the growing access we have to media images of the past that rather than represent history or an event we did not live through they simply 1 become history.0F “Rhythm Nation” materializes this strenuous period in which our lives, communication, and perception of time and space become mediated through the televisual and rarely exist outside of it. During an era where “I want my MTV” was feverishly chanted by teenagers across the country, “Rhythm Nation 1814” is a time capsule of how television began to permeate our quotidian experiences in an irrevocable way. -

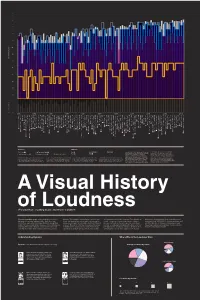

A Visual History of Loudness

0 -5 -10 -15 -20 -25 -30 RMS levels In negative decibles -35 -40 -45 -50 -55 -60 0 -5 peak levels In negative decibles -10 1979 • 1982 • 1985 • 1988 • 1991 • 1994 • 1997 • 2000 • 2003 • 2006 • 2009 Too Much Heaven – Bee Gees █ Da Ya Think I'm Sexy? – Rod Stewart █ Babe – Styx █ Rock With You Michael Jackson – Off The Wall █ Call Me (Theme From American Gigolo) – Blondie █ Lady – Kenny Rogers █ (Just Like) Starting Over – John Lennon & Yoko Ono █ Bettie Davis Eyes – Kim Carnes █ Physical – Olivia Newton-John █ Centerfold – The J. Geils Band █ Jack & Diane – John Cougar █ Eye Of The Tiger – Survivor █ Billie Jean – Michael Jackson █ Every Breath You Take – The Police █ All Night Long (All Night) – Lionel Richie █ Jump – Van Halen █ When Doves Cry – Prince █ Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go – Wham! █ Like A Virgin – Madonna █ GRAPH KEY SONG KEY Shout – Tears For Fears █ from the primary chorus, or most definitive RMS Levels █ High Frequency Peaks █ Pop █ MoneyCountry/Ballad For Nothing █ – Dire Straits █ Hip Hop █ sounds in the middle frequencies of the song, which are the frequencies that most everyday moment of each song. Three songs were Low Frequency Peaks █ Mid Frequency Peaks █ Absolute Peak Level █ Rock █ RockR&B Me █ Amadeus – Falco █ sounds are involved with, including the selected from each year over the last three Greatest Love of All – Whitney Houston █ human voice (1000hz). The high frequency decades, one from each trimester, with prece- peaks are the loudest sounds in the higher, dence given to songs with the most weeks at The absolute loudness of a song is called it's peak peak at zero, or the maximum volume alloted by decreasing the space betweenTrue the softestColors and– Cyndi Lauperestimated █ beyond the threshold of zero. -

Extra Song Chips POPAU1.POPAU2.POPAU3.POPAU4

EXTRA SONG CHIPS FOR SSM-PK3 THEY ARE ONLY AVAILABLE FROM SANYO SPARE PARTS RRP $99.00 EACH POPAU1 SONG NO. TITLE ARTIST 501 A HORSE WITH NO NAME AMERICA 502 ACT NATURALLY BUCK OWENS 503 AIN'T THAT A SHAME FATS DOMINO 504 ALL THE MAN THAT I NEED WHITNEY HOUSTON 505 AND ALL THAT JAZZ MUSICAL - CHICAGO 506 ANOTHER SAD LOVE SONG TONI BRAXTON 507 AIN'T NOTHIN' GOIN BUT THE RENT GWE GUTHRIE 508 BABY I NEED YOUR LOVING THE FOUR TOPS 509 BAD MICHAEL JACKSON 510 BEAT IT MICHAEL JACKSON 511 BENNIE & THE JETS ELTON JOHN 512 BLACK OR WHITE MICHAEL JACKSON 513 BLAME IT ON THE BOSSA NOVA EYDIE GORME 514 BOOGIE WOOGIE BUGLE BOY BETTE MIDLER 515 BORN TO WANDER RARE EARTH 516 CAN'T GET ENOUGH OF YOU BABY SMASHMOUTH 517 CAUGHT UP IN THE RAPTURE ANITA BAKER 518 CHURCH OF THE POISON MIND CULTURE CLUB 519 CONTROL JANET JACKSON 520 CRAZY PATSY CLINE 521 COOL AS ICE (EVERYBODY GET LOOSE) VANILLA ICE 522 C'MON AND GET MY LOVE D. MOB. 523 DAYDREAM BELIEVER THE MONKEES 524 DEVIL WENT DOWN TO GEORGIA CHARLIE DANIELS BAND 525 DO WOP (THAT THING) LAURYN HILL 526 DO RIGHT WOMAN, DO RIGHT MAN ARETHA FRANKLIN/ BARBARA MANDRELL 527 DON'T STOP TILL YOU GET ENOUGH MICHAEL JACKSON 528 DUST IN THE WIND KANSAS 529 EASE ON DOWN THE ROAD MUSICAL - THE WIZ 530 ENDLESS LOVE MOVIE - ENDLESS LOVE 531 EVERYTHING IS EVERYTHING LAURYN HILL 532 EVERYTHING I OWN BREAD 533 FAMILY PORTRAIT PINK 534 FINALLY CECE PENISTON 535 FOREVER MY LADY JODECI 536 FREEBIRD LYNYRD SKYNYRD 537 GEORGY GIRL THE SEEKERS 538 GET BACK THE BEATLES 539 GIVE ME JUST A LITTLE MORE TIME KYLIE MINOGUE 540 GO WHERE -

Songs by Title

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Title www.adj2.com Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly A Dozen Roses Monica (I Got That) Boom Boom Britney Spears & Ying Yang Twins A Heady Tale Fratellis, The (I Just Wanna) Fly Sugar Ray A House Is Not A Home Luther Vandross (I'll Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra A Long Walk Jill Scott + 1 Martin Solveig & Sam White A Man Without Love Englebert Humperdinck 1 2 3 Miami Sound Machine A Matter Of Trust Billy Joel 1 2 3 4 I Love You Plain White T's A Milli Lil Wayne 1 2 Step Ciara & Missy Elliott A Moment Like This,zip Leona 1 Thing Amerie A Moument Like This Kelly Clarkson 10 Million People Example A Mover El Cu La Sonora Dinamita 10,000 Hours Dan + Shay, Justin Bieber A Night To Remember High School Musical 3 10,000 Nights Alphabeat A Song For Mama Boyz Ii Men 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters A Sunday Kind Of Love Reba McEntire 12 Days Of X Various A Team, The Ed Sheeran 123 Gloria Estefan A Thin Line Between Love & Hate H-Town 1234 Feist A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton 16 @ War Karina A Thousand Years Christina Perri 17 Forever Metro Station A Whole New World Zayn, Zhavia Ward 19-2000 Gorillaz ABC Jackson 5 1973 James Blunt Abc 123 Levert 1982 Randy Travis Abide With Me West Angeles Gogic 1985 Bowling For Soup About A Girl Sugababes 1999 Prince About You Now Sugababes 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The Abracadabra Steve Miller Band 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Nine Days 20 Years Ago Kenny Rogers Acapella Kelis 21 Guns Green Day According To You Orianthi 21 Questions 50 Cent Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus 21st Century Breakdown Green Day Act A Fool Ludacris 21st Century Girl Willow Smith Actos De Un Tonto Conjunto Primavera 22 Lily Allen Adam Ant Goody Two Shoes 22 Taylor Swift Adams Song Blink 182 24K Magic Bruno Mars Addicted To You Avicii 29 Palms Robert Plant Addictive Truth Hurts & Rakim 2U David Guetta Ft. -

Lop40* with SHADOE SHV~No

AME ICAN *lOP40* WITH SHADOE SHV~No ***COMPACT DISC #1, TRACK 10, HAS 1KHz REFERENCE TONE*** TOPICAL PROMOS TOPICAL PROMOS FOR SHOW #3 ARE LOCATED ON CD DISC 4 1 TRACKS 6&7 DO NOT USE AFTER SHOW #3 1. HIT JUSTIFICATION Hi, I'm Shadoe stevens, AT40. Last week Madonna spent her second week on top of the Billboard chart with "Justify My Love". But meanwhile down below, the band Damn Yankees waved their star-spangled banner at #3 with "High Enough", and Janet Jackson leaped to #4 with "Love Will Never Do (Without You)". Will Madonna make it three weeks on top? Will Damn Yankees find only #1 is "Hi9h Enough"? Or will Janet Jackson insist the pop peak w~ll never do without her? There's only one way to find out, when we count 'em down right here on American Top M1 r r.:~:· al 'l'ag) 2. JACKSON JUGGERNAUT Hey, Shadoe stevens, American Top 40. Well, she was the top woman of 1990 and had the year's biggest album with "Rhythm Nation". So far, it's given her seven top tens, tieing the all-time record. Three have hit #1: "Miss You Much", "Escapade", and "Black Cat". And the Janet Jackson juggernaut is on the move again. Last week, she leaped from #7 to #4 on the official Billboard chart with "Love Will Never Do (Without You)". Will it capture the pop prize on top for a fourth Rhythm Natitm rumbler at #1? Ah, D'Shadoe knows, on American Tc>p 40! (Local Tag) ***FOR YOUR CONVENIENCE, WE HAVE PLACED A 20 HZ TONE AT -10 DB AT THE END OF OUR NETWORK COMMERCIAL BREAKS TO ACCOMMODATE AUTOMATED AND SEMI-AUTOMATED STATIONS*** I ABC Watermark I 0 OABC RADIO Nil WORKS 3575 Cahuenga Blvd.