Living on the Edge Black Metal and the Refusal of Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Een Greep Uit De Cd-Releases 2012

Een greep uit de cd-releases 2012 Artiest/groep Titel 1 Aborted Global flatline 2 Allah -las Allah -las 3 Absynthe Minded As it ever was 4 Accept Stalingrad 5 Adrenaline Mob (Russel Allen & Mike Portnoy) Omerta 6 After All Dawn of the enforcer 7 Aimee Mann Charmer 8 Air La voyage dans la lune 9 Alabama Shakes Boys & girls 10 Alanis Morissette Havoc and bright lights 11 Alberta Cross Songs of Patience 12 Alicia Keys Girl on fire 13 Alt J An AwsoME Wave 14 Amadou & Mariam Folila 15 Amenra Mass V 16 Amos Lee As the crow flies -6 track EP- 17 Amy MacDonald Life in a beautiful light 18 Anathema Weather systems 19 Andrei Lugovski Incanto 20 Andy Burrows (Razorlight) Company 21 Angus Stone Broken brights 22 Animal Collective Centipede Hz 23 Anneke Van Giersbergen Everything is changing 24 Antony & The Johnsons Cut the world 25 Architects Daybreaker 26 Ariel Pink Haunted Graffitti 27 Arjen Anthony Lucassen Lost in the new real (2cd) 28 Arno Future vintage 29 Aroma Di Amore Samizdat 30 As I Lay Dying Awakened 31 Balthazar Rats 32 Band Of Horses Mirage rock 33 Band Of Skulls Sweet sour 34 Baroness Yellow & green 35 Bat For Lashes Haunted man 36 Beach Boys That's why god made the radio 37 Beach House Bloom 38 Believo ! Hard to Find 39 Ben Harper By my side 40 Berlaen De loatste man 41 Billy Talent Dead silence 42 Biohazard Reborn in defiance 43 Black Country Communion Afterglow 44 Blaudzun Heavy Flowers 45 Bloc Party Four 46 Blood Red Shoes In time to voices 47 Bob Dylan Tempest (cd/cd deluxe+book) 48 Bob Mould Silver age 49 Bobby Womack The Bravest -

Ihsahn to Premiere New Show at Inferno 2020

IHSAHN TO PREMIERE NEW SHOW AT INFERNO 2020 We can reveal that Ihsahn is currently in the studio putting the final touches on brand new material to be released via Candlelight Records. For Inferno 2020, Ihsahn will be perform this new material live for the first time, premiering a specialized set rooted in the blackest corners of his musical palette: "The music I’m working on distills the most basic, black metal aesthetics of my music. Keeping to rather traditional arrangements and expressed with Norwegian lyrics, I explore the core elements of my musical background. These new songs will form the basis for some conceptualized shows, which I shall debut at Inferno in 2020." More details coming soon… INFERNO METAL FESTIVAL 2020: MAYHEM IHSAHN – KAMPFAR – VED BUENS ENDE – CADAVER – MYRKSKOG – BÖLZER DJERV – SYLVAINE – VALKYRJA + MANY MORE TO BE ANNOUNCED IHSAHN Ihsahn comes from Notodden, Norway, where he at the age of thirteen started playing in what developed into one of the world’s most influential black metal bands, Emperor. At only seventeen he recorded and performed “In the Nightside Eclipse”, which has many times been voted as one of the top metal albums of all time. After Emperor released their last album, “Prometheus - The Discipline of Fire & Demise” in 2001, Ihsahn has focused on is solo work and has by now released seven albums under the name Ihsahn. Now Ihsahn will return to Inferno Metal Festival for a special premiere of his new show. Make sure you don’t miss it. https://www.facebook.com/ihsahnmusic/ INFERNO METAL FESTIVAL 2020 Inferno Metal Festival 2020 marks the 20 years anniversary of the festival. -

Chao Ab Ordo(*)

CHAO AB ORDO Chao ab Ordo(*) (*) The source of the oft used Latin phrase Ordo ab Chao has its roots deeply embedded in the origin story of the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry in the Americas. Georges M. Halpern, MD, DSc with Yves P. Huin 1 CHAO AB ORDO Antipasti “Here's to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently. They're not fond of rules. And they have no respect for the status quo. You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them. About the only thing you can't do is ignore them. Because they change things. They push the human race forward. And while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius. Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world, are the ones who do.” Rob Siltanen You may never have read a single line of La Divina Commedia, and yet you’ve been influenced by it. But it’s just one line of the 14,233 that make up The Divine Comedy. The three-part epic poem published in 1320 by the Florentine bureaucrat -turned visionary storyteller- Dante Alighieri. In late 13th Century Florence, books were sold in apothecaries, a solid evidence that words on paper (or parchment) could affect minds with their ideas, as much as any drug. And what an addiction The Divine Comedy inspired: a literary work endlessly adapted, pinched from, referenced and remixed, inspiring painters and sculptors for centuries! More than the authors of the Bible itself, Dante provided us with the vision of Hell that remains with us and has been painted by Botticelli and Blake, Delacroix and Dalí, turned into sculpture by Rodin –whose The Kiss depicts Dante’s damned lovers Paolo and Francesca – and illustrated in the pages of X-Men comics by John Romita. -

![HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8672/how-black-is-black-metal-journalismus-nachrichten-von-heute-488672.webp)

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] Nachrichten Von Heute

HOW BLACK IS BLACK METAL [JOURNALISMUS] nachrichten von heute Kevin Coogan - Lords of Chaos (LOC), a recent book-length examination of the “Satanic” black metal music scene, is less concerned with sound than fury. Authors Michael Moynihan and Didrik Sederlind zero in on Norway, where a tiny clique of black metal musicians torched some churches in 1992. The church burners’ own place of worship was a small Oslo record store called Helvete (Hell). Helvete was run by the godfather of Norwegian black metal, 0ystein Aarseth (“Euronymous”, or “Prince of Death”), who first brought black metal to Norway with his group Mayhem and his Deathlike Silence record label. One early member of the movement, “Frost” from the band Satyricon, recalled his first visit to Helvete: I felt like this was the place I had always dreamed about being in. It was a kick in the back. The black painted walls, the bizarre fitted out with inverted crosses, weapons, candelabra etc. And then just the downright evil atmosphere...it was just perfect. Frost was also impressed at how talented Euronymous was in “bringing forth the evil in people – and bringing the right people together” and then dominating them. “With a scene ruled by the firm hand of Euronymous,” Frost reminisced, “one could not avoid a certain herd-mentality. There were strict codes for what was accept- ed.” Euronymous may have honed his dictatorial skills while a member of Red Ungdom (Red Youth), the youth wing of the Marxist/Leninist Communist Workers Party, a Stalinist/Maoist outfit that idolized Pol Pot. All who wanted to be part of black metal’s inner core “had to please the leader in one way or the other.” Yet to Frost, Euronymous’s control over the scene was precisely “what made it so special and obscure, creating a center of dark, evil energies and inspiration.” Lords of Chaos, however, is far less interested in Euronymous than in the man who killed him, Varg Vikemes from the one-man group Burzum. -

Identitarian Movement

Identitarian movement The identitarian movement (otherwise known as Identitarianism) is a European and North American[2][3][4][5] white nationalist[5][6][7] movement originating in France. The identitarians began as a youth movement deriving from the French Nouvelle Droite (New Right) Génération Identitaire and the anti-Zionist and National Bolshevik Unité Radicale. Although initially the youth wing of the anti- immigration and nativist Bloc Identitaire, it has taken on its own identity and is largely classified as a separate entity altogether.[8] The movement is a part of the counter-jihad movement,[9] with many in it believing in the white genocide conspiracy theory.[10][11] It also supports the concept of a "Europe of 100 flags".[12] The movement has also been described as being a part of the global alt-right.[13][14][15] Lambda, the symbol of the Identitarian movement; intended to commemorate the Battle of Thermopylae[1] Contents Geography In Europe In North America Links to violence and neo-Nazism References Further reading External links Geography In Europe The main Identitarian youth movement is Génération identitaire in France, a youth wing of the Bloc identitaire party. In Sweden, identitarianism has been promoted by a now inactive organisation Nordiska förbundet which initiated the online encyclopedia Metapedia.[16] It then mobilised a number of "independent activist groups" similar to their French counterparts, among them Reaktion Östergötland and Identitet Väst, who performed a number of political actions, marked by a certain -

Darkthrone Is Absolutely Not a Political Band and We Never Were

THE ‘FAILURE’ OF YOUTH CULTURE: REFLEXIVITY, MUSIC AND POLITICS IN THE BLACK METAL SCENE Dr Keith Kahn-Harris, Independent social researcher 57 Goring Road London N11 2BT Tel: 0208 881 5742 E-mail: [email protected] Dr Keith Kahn-Harris (né Harris) received his PhD on the sociology of the global Extreme Metal music scene from Goldsmiths College in 2001. Since then he has been a fellow at the Mandel School for Advanced Jewish Educational Leadership, Jerusalem and a visiting fellow at the Monash University Centre for Jewish Civilization, Melbourne. He is currently working on a variety of projects as an independent social researcher in the British Jewish community. THE ‘FAILURE’ OF YOUTH CULTURE: REFLEXIVITY, MUSIC AND POLITICS IN THE BLACK METAL SCENE Abstract: This paper examines an enduring question raised by subcultural studies – how youth culture can be challenging and transgressive yet ‘fail’ to produce wider social change. This question is addressed through the case study of the Black Metal music scene. The Black Metal scene flirts with violent racism yet has resisted embracing outright fascism. The paper argues that this is due to the way in which music is ‘reflexively anti-reflexively’ constructed as a depoliticising category. It is argued that an investigation of such forms of reflexivity might explain the enduring ‘failure’ of youth cultures to change more than their immediate surroundings. Keywords: Subculture, reflexivity, politics, Black Metal, racism, youth culture, scenes. 1 Introduction: Subcultural theory and the ‘failure’ of youth culture It is hardly necessary to point out that cultural studies, and in particular the study of youth culture, owes a massive debt to subcultural theory, as developed by members of and those allied to the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies in the 1970s (e.g. -

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal *

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal * Stephen S. Hudson NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.1/mto.21.27.1.hudson.php KEYWORDS: Heavy Metal, Formenlehre, Form Perception, Embodied Cognition, Corpus Study, Musical Meaning, Genre ABSTRACT: This article presents a new framework for analyzing compound AABA form in heavy metal music, inspired by normative theories of form in the Formenlehre tradition. A corpus study shows that a particular riff-based version of compound AABA, with a specific style of buildup intro (Aas 2015) and other characteristic features, is normative in mainstream styles of the metal genre. Within this norm, individual artists have their own strategies (Meyer 1989) for manifesting compound AABA form. These strategies afford stylistic distinctions between bands, so that differences in form can be said to signify aesthetic posing or social positioning—a different kind of signification than the programmatic or semantic communication that has been the focus of most existing music theory research in areas like topic theory or musical semiotics. This article concludes with an exploration of how these different formal strategies embody different qualities of physical movement or feelings of motion, arguing that in making stylistic distinctions and identifying with a particular subgenre or style, we imagine that these distinct ways of moving correlate with (sub)genre rhetoric and the physical stances of imagined communities of fans (Anderson 1983, Hill 2016). Received January 2020 Volume 27, Number 1, March 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory “Your favorite songs all sound the same — and that’s okay . -

Career Break Or a New Career? Extremist Foreign Fighters in Ukraine

Career Break or a New Career? Extremist Foreign Fighters in Ukraine By Kacper Rekawek (@KacperRekawek) April 2020 Counter Extremism Project (CEP) Germany www.counterextremism.com I @FightExtremism CONTENTS: ABOUT CEP/ABOUT THE AUTHOR 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 INTRODUCTION 5 SECTION I INTRODUCING FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN THE WAR IN UKRAINE 7 THE XRW FOREIGN FIGHTER: A WORLDVIEW 9 TALKING TO FOREIGN FIGHTERS: THEIR WORDS AND SYMBOLS 11 THE “UNHAPPY” FOREING FIGHTERS 13 CIVIL WAR? 15 SECTION II WHY THEY FIGHT 17 A CAREER BREAK OR NEW CAREER? 18 FOREIGN FIGHTERS WAR LOGISTICS 22 SECTION III FOREIGN FIGHTERS AS A THREAT? 25 TENTATIVE CONCLUSION: NEITHER A UKRAINIAN 29 NOR A WESTERN PROBLEM? ENDNOTES 31 Counter Extremism Project (CEP) 1 counterextremism.com About CEP The Counter Extremism Project (CEP) is a not-for-profit, non-partisan, international policy organization formed to combat the growing threat from extremist ideologies. Led by a renowned group of former world leaders and diplomats it combats extremism by pressuring financial and material support networks; countering the narrative of extremists and their online recruitment; and advocating for smart laws, policies, and regulations. About the author Kacper Rekawek, PhD is an affiliated researcher at CEP and a GLOBSEC associate fellow. Between 2016 and 2019 he led the latter’s national security program. Previously, he worked at the Polish Institute of International Affairs (PISM) and University of Social Sciences in Warsaw, Poland. He held Paul Wilkinson Memorial Fellowship at the Handa Centre -

Hipster Black Metal?

Hipster Black Metal? Deafheaven’s Sunbather and the Evolution of an (Un) popular Genre Paola Ferrero A couple of months ago a guy walks into a bar in Brooklyn and strikes up a conversation with the bartenders about heavy metal. The guy happens to mention that Deafheaven, an up-and-coming American black metal (BM) band, is going to perform at Saint Vitus, the local metal concert venue, in a couple of weeks. The bartenders immediately become confrontational, denying Deafheaven the BM ‘label of authenticity’: the band, according to them, plays ‘hipster metal’ and their singer, George Clarke, clearly sports a hipster hairstyle. Good thing they probably did not know who they were talking to: the ‘guy’ in our story is, in fact, Jonah Bayer, a contributor to Noisey, the music magazine of Vice, considered to be one of the bastions of hipster online culture. The product of that conversation, a piece entitled ‘Why are black metal fans such elitist assholes?’ was almost certainly intended as a humorous nod to the ongoing debate, generated mainly by music webzines and their readers, over Deafheaven’s inclusion in the BM canon. The article features a promo picture of the band, two young, clean- shaven guys, wearing indistinct clothing, with short haircuts and mild, neutral facial expressions, their faces made to look like they were ironically wearing black and white make up, the typical ‘corpse-paint’ of traditional, early BM. It certainly did not help that Bayer also included a picture of Inquisition, a historical BM band from Colombia formed in the early 1990s, and ridiculed their corpse-paint and black cloaks attire with the following caption: ‘Here’s what you’re defending, black metal purists. -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

d o n e i t . MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS R Tit e l der M a s t erarbei t / Titl e of the Ma s t er‘ s Thes i s e „What Never Was": a Lis t eni ng to th e Genesis of B lack Met al d M o v erf a ss t v on / s ubm itted by r Florian Walch, B A e : anges t rebt e r a k adem is c her Grad / i n par ti al f ul fi l men t o f t he requ i re men t s for the deg ree of I Ma s ter o f Art s ( MA ) n t e Wien , 2016 / V i enna 2016 r v i Studien k enn z ahl l t. Studienbla t t / A 066 836 e deg r ee p rogramm e c ode as i t appea r s o n t he st ude nt r eco rd s hee t: w Studien r i c h tu ng l t. Studienbla tt / Mas t er s t udi um Mu s i k w is s ens c ha ft U G 2002 : deg r ee p r o g r amme as i t appea r s o n t he s tud e nt r eco r d s h eet : B et r eut v on / S uper v i s or: U ni v .-Pr o f. Dr . Mi c hele C a l ella F e n t i z |l 2 3 4 Table of Contents 1. -

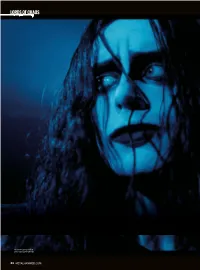

Lords of Chaos

LORDS OF CHAOS US actor Rory Culkin portrays Euronymous 66 METALHAMMER.COM MHR316.lordsofchaos.indd 66 10/24/18 4:32 PM LORDS OF CHAOS WORDS: JONATHAN SELZER Exploring the rise of the notorious Norwegian black metal scene, Lords Of Chaos has divided fans and artists alike. We talk to director Jonas Åkerlund and Mayhem’s Necrobutcher on the eve of its release he story was never going to go away. Twenty-fi ve years after the death of Mayhem co-founder Øystein ‘Euronymous’ Aarseth at the hands of his friend, brief bandmate and Burzum founder Varg Vikernes in Oslo, the accompanying tale Tof suicide, betrayal, church burnings and “IF THERE’S AN murder has remained a source of mystery, lore and rampant speculation, aided by the AFTERLIFE, DEAD AND fact that the black metal movement Mayhem founded – and the band themselves – are still EURONYMOUS WILL BE going strong. In an act of fate worthy of the tale at VERY FUCKING HAPPY” their heart, two very diff erent, but often JØrn ‘neCroBuTCHer’ sTuBBerud complementary histories of Mayhem have METALHAMMER.COM 67 MHR316.lordsofchaos.indd 67 10/24/18 4:32 PM LORDS OF CHAOS The lords of chaos are also regents of tomfoolery emerged. The first is the long-awaited, and Photos of the True feared, movie, Lords Of Chaos, directed by Mayhem were “I WANTED recreated for the one-time drummer for proto-black metallers movie (below) Bathory and celebrated video director, Jonas TO MAKE Åkerlund. The second, The Death Archives, by Mayhem’s other founder, bassist Jørn A MOVIE THAT ‘Necrobutcher’ Stubberud, is a personal recounting of Mayhem’s first 10 years, along HUMANISES with reams of photographic documentation. -

Mayhem & Death

Download Mayhem & Death [Full Online>> Death Taxes And Mistletoe Mayhem Kelly ... Mayhem & Death PDF 58,95MB Death Taxes And Mistletoe Mayhem Kelly Diane Free DownloadSearching for Death Taxes And Mistletoe Mayhem Kelly Diane Do you really need this pdf of Death Taxes And Mistletoe Mayhem Kelly Diane It takes me 66 hours just to found the right download link, and another 2 hours to validate it. Internet could be heartless to us who looking for free thing. Télécharger The Death Archives: Mayhem 1984-94 PDF Jorn Mayhem & Death Télécharger The Death Archives: Mayhem 1984-94 Livre PDF Jorn " Necrobutcher" Stubberud Livres en ligne PDF The Death Archives: Mayhem 1984-94. Télécharger et lire des livres en ligne The Death Archives: Mayhem 1984-94 Online ePub/PDF/Audible/Kindle, son moyen facile de diffuser The Death Archives: Mayhem 1984-94 livres pour plusieurs appareils. Ebook : Death Punchd Surviving Five Finger Death Punchs ... Mayhem & Death Death Punchd Surviving Five Finger Death Punchs Metal Mayhem Epub Download Related Book Ebook Pdf Death Punchd Surviving Five Finger Death Punchs Metal Mayhem : - 2006 Chrysler Pacifica Engine Diagram- 2006 Ford Five Hundred Service Manual- 2006 Ford Focus Fuse Box Télécharger The Death Archives: Mayhem 1984-94 PDF Jorn Mayhem & Death The Death Archives: Mayhem 1984-94 Beaucoup de gens essaient de rechercher ces livres dans le moteur de recherche avec plusieurs requêtes telles que [Télécharger] le Livre The Death Archives: Mayhem 1984-94 en Format PDF, Télécharger The Death Archives: Mayhem 1984-94 Livre Ebook PDF pour obtenir livre gratuit. Of The Blade Revolutions Mayhem Betrayal Glory And Death ..