The Nightwatchers’ a Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where's Brock?

• • ... , . Volume 30, Issue 8 Concordia College, 275 North Syndicate, St. Paul, MN 55104 Friday Febraury 17, 1995 Where's Brock? by Amy MacFee Why the resignation? John Brockopp replies, agreement with Concordia that he wouldn't have Department from being almost exclusively staffed "the policy [at Service Master] is to move manage- to leave if he took the supervisor position." In fact, by students (which did not work out) to being Everyone knew John Brockopp; he was the ment people after a certain number of years." But, he asked Chitty if he (Brockopp) would have to be staffed by part time employees. Chitty comment- Custodial Department Supervisor. Where has he Bob Zuniga, a custodian who worked under transferred, and Chitty responded, ("Brock' does ed, "John was key in training and scheduling and gone? Unfortunately, Brockopp resigned his posi- Brockopp, felt "he was forced to leave," and was a not have to move unless 'Brock' wants to move." getting that job done." Brock is remembered for tion and served his last day on February 10. He "victim of two long term problems in the depart- But, Brockopp did have to leave. Chitty explained, his hard work said Chitty: "It wouldn't be right to was offered a choice between four different man- ment: lack of money; and lack of man power." "Our intention was to have John in the [supervi- say he didn't give it everything he had." agerial positions, but he would have had to relo- However, John Chitty, head of the Custodial sor] position as long as he filled the position, but Brockopp assisted Zuniga in several of his cate upon acceptance of them. -

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

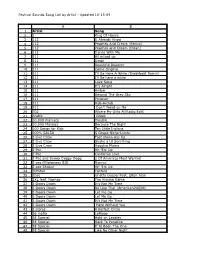

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

3000 Unique Captions, Status, Quotes

3000 UNIQUE CAPTIONS, STATUS, QUOTES S I D D H A R T H Introduction Hey Guys! I am Siddharth. Here I have compiled 3000 unique Instagram captions, quotes, status just for you! The idea behind creating this e-book was the love I got from you all from past 2 years. So here is a small gesture in a way of saying thank you to all for loving us and our captions. I know the need of captions has risen so fast that people are not getting unique captions for their amazing posts. So that's why my friend, I have got you this amazing list of captions which you will never find anywhere on internet! And do you know what's the best part is? That this book is with you forever! You can literally post daily on your social media accounts for BACK-TO-BACK 3000 DAYS, which is actually 8 YEARS! That is INSANE, NO?? So, now that you have literally trashed your tension of what to post everyday, you can now chill, relax and select the best caption for next day! Table Of Contents 1.Life Inspirational Captions....................... Pg No. 01 2.Cool Attitude Captions............................. Pg No. 06 3.Love Captions............................................. Pg No. 08 4.Break-Up Quotes....................................... Pg No. 09 5.Captions For Friends................................. Pg No. 11 6.Motivational Captions............................... Pg No. 13 7.Good Morning Quotes.............................. Pg No. 14 8.Captions For Pictures................................ Pg No. 16 9.Selfie Captions............................................ Pg No. 19 10.Mirror Selfie Captions............................... Pg No. 24 11.Video Call Captions.................................. -

Sabbath Sentinel September–October 2009 Volume 61, No

SabbathThe Sentinel September–October 2009 What are her religious rights in public school? BSA — The Bible Sabbath Association Jesus said, “the Son of Man is Lord also of the Sabbath” The Sabbath Sentinel September–October 2009 Volume 61, No. 5 Issue 539 FEATURES The Sabbath Sentinel is published bimonthly by The Bible Sabbath Association, 802 N. W. 21st Ave., Battle Ground, WA 98604. Copyright 4 Last Man Standing © 2009, by The Bible Sabbath Association. Printed in the U.S.A. All by Kenneth Westby rights reserved. Reproduction in any form without written permission is prohibited. Nonprofit bulk rate postage paid at Rapid City, South 6 First Steps to Revitalizing your Marriage Dakota. Editor: Kenneth Ryland, [email protected]. by Pastor David Guerrero Associate Editors: Julia Benson & Shirley Nickels 8 ALL the Commandments BSA’s Board of Directors for 2007-2011: by Greg Sereda President: John Paul Howell, [email protected] Vice President: Marsha Basner 11 I Can, but Will I? Vice President: June Narber by Bryant Buck Treasurer: Bryan Burrell Secretary: Calvin Burrell 12 The Divine Subjectivity Office Manager—Battle Ground, WA, Office: Shirley Nickels by Terril D. Littrell, Ph. D. Directors At Large: Darrell Estep, Calvin Burrell, Bryan Burrell, Rico Cortes, John Guffey, Dusti Howell, Tom Justus, Earl Lewis, Kenneth 16 Is Obedience a Condition of Salvation Ryland by Marvin Moore Subscriptions: Call (888) 687-5191 or write to: The Bible Sabbath Association, 802 N. W. 21st Ave., Battle Ground, WA 98604 or contact 20 Putting Faith in God First, us at the office nearest you (see international addresses below). -

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc Number Disc Count Track Number Track Count Year Date Mod ified Date Added Bit Rate Sample Rate Volume Adjustment Kind Equalizer Comments Plays Last Played Skips Last Ski ppedDancing MyQueen Rating ABBA LocationBenny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus/Stig Anderson ABBA For ever Gold I Rock 3715072 231 1 1 1 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBA Forever Gold I:0 1Knowing Dancing me, Queen.mp3 knowing you ABBA Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus/Stig Anderson ABBA Forever Gold I Rock 3885158 241 1 1 2 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBA Forever Gold I:0 2Take Knowing a chance me, knowingon me you.mp3 ABBA Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus ABBA Forever Gol d I Rock 3924028 244 1 1 3 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file 2 9/10/11 10:56 PM Audio:ABBA:ABBA ForeverMamma mia Gold I:03 ABBA Take a Bennychance Andersson/Björn on me.mp3 Ulvaeus/Stig Anderson ABBA For ever Gold I Rock 3428328 213 1 1 4 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file 2 9/10/11 10:59 PM Audio:ABBA:ABBA ForeverLay all Goldyour I:04love Mammaon me mia.mp3 ABBA Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus ABBA Forever Gol d I Rock 4401337 274 1 1 5 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBA Forever Gold I:0 5Super Lay alltrouper your love ABBA on me.mp3 Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus ABBA Forever Gold I Rock 4081599 254 1 1 6 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBAI -

THE WAY WE SAY GOODBYE and OTHER STORIES a Thesis

THE WAY WE SAY GOODBYE AND OTHER STORIES A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts Gillian Trownson August, 2011 THE WAY WE SAY GOODBYE AND OTHER STORIES Gillian Trownson Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Mr. Robert Pope Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Department Chair Dr. Mary Biddinger Dr. Michael Schuldiner _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Robert Miltner Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Date Mr. Eric Wasserman ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page BUS RIDE………………………………………………………………………………...1 COFFEE AND CIGARETTES………………………………………………………….19 PIZZA DAY……………………………………………………………………………...35 THE DATE………………………………………………………………………………51 THE RESIGNATION……………………………………………………………………69 THE BATTLE OF WHO COULD CARE LESS………………………………………..77 WAITING FOR THE FLOOD…………………………………………………………..94 TRUE LOVE WAITS………………………………………………………………….105 THE WAY WE SAY GOODBYE……………………………………………………..115 iii BUS RIDE Phil and Kendall boarded their first bus in Pittsburgh. As the driver threw their luggage into the baggage compartment, Kendall rocked back and forth, crumpling her skirt in her hands, excited to meet her uncle Rick for the first time. She had insisted on wearing her best dress, a yellow taffeta and tulle princess gown from Halloween six months earlier, and Phil let her, even though he knew the trip to Amarillo was going to take nearly a day and a half. Kendall had foregone the plastic tiara only because of Phil’s insistence that it would be difficult for her to sleep with the “silver” digging into her scalp. Phil was careful to refer to the tiara as real silver, careful to always let Kendall believe she was a real princess. -

The Fifth Commandment and Translations of Other Short

THE FIFTH COMMANDMENT AND TRANSLATIONS OF OTHER SHORT STORIES BY ROCÍO QESPI by ALEKSANDRA M. CARBAJAL A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Spanish written under the direction of Phyllis Zatlin, Ph.D. and approved by ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2008 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Fifth Commandment and Translations of Other Short Stories by Rocío Qespi By ALEKSANDRA M. CARBAJAL Thesis Director: Phyllis Zatlin, Ph.D. Rocío Qespi is a Peruvian author who writes short stories that center around the themes of love, chess, and personal experiences. Her prose is a rich tapestry of allusions to the work of other Latin American authors and artists as well as a reference to events from her own life. As her translator, I had the opportunity to work closely with the author as I resolved problems encountered during the process of translating her prose. Following a brief introduction that describes these problems and their solutions, is a selection of the translated stories taken from the collection El cuarto mandamiento, which has been published by Mundo Ajeno in Peru. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks to Professor Phyllis Zatlin, Professor Jorge Marcone, Professor Marcy Schwartz, Jeff Saxon, Mary Katherine Hogan, and the author, Rocío Qespi, for their guidance, creative and generous -

Book: Rhoda Weyr, My Agent; Annie Gottlieb, My Collaborator; Amanda Vaill, My Editor; and Paulette Lundquist, Who Did Both Her Job and Mine at the Office

WISHCRAFT How to Get What You Really Want BARBARA SHER with Annie Gottlieb Copyright © 1979 Barbara Sher http://www.BarbaraSher.com To my mother, who has always believed in me. ii Acknowledgments Because I tried to be a good person, fate dropped into my life just the people I needed to get my notions into a book: Rhoda Weyr, my agent; Annie Gottlieb, my collaborator; Amanda Vaill, my editor; and Paulette Lundquist, who did both her job and mine at the office. They are the best team anyone could ever wish for. Without them there would have been no book. Five men belong here as well: John, who kept me going when the going got rough; Danny, Matthew and Freddy, who were always proud of me (and kept house—such as it was—for ten years); and my Dad, who showed me how to be a person who trusted herself and didn't quit. Without them, there would have been no Barbara. –BARBARA SHER Special thanks to my grandmothers, for the gift of words: Anne Preaskil Stern, who taught me the alphabet; the late Dorothy Kuh Gottlieb, who shared with me her passion for books. And to Jacques Sandulescu, Margaret Webb, Gita, Harry and Jean Gottlieb, and J. Barnes and Mina Creech. –ANNIE GOTTLIEB iii Contents INTRODUCTION One THE CARE AND FEEDING OF HUMAN GENIUS 1 Who Do You Think You Are? 2 The Environment That Creates Winners Two WISHING 3 Stylesearch 4 Goalsearch 5 Hard Times, or The Power of Negative Thinking Three CRAFTING I: PLOTTING THE PATH TO YOUR GOAL 6 Brainstorming 7 Barn-raising 8 Working with Time iv Four CRAFTING II: MOVING AND SHAKING 9 Winning Through Timidation, or First Aid for Fear 10 Don't-Do-It-Yourself 11 Proceeding EPILOGUE: LEARNING TO LIVE WITH SUCCESS v Introduction This book is designed to make you a winner. -

Groundbreaking Scheduled for New Flagler College Library

mIAT'S INSIDE... Why Study Abroad? Editorial/Commentary... Page 2 Page 7 Arts & Entertainment... Page 8 Music Reviews ... Page 10 1994 - 95 Official Guide to Clubs Sports ... Page 11 Pa e 8 VOL. XXIIII, NO. 1 S A I N T A U G U S T I N E , F L O R I D A September 6, 1994 Groundbreaking scheduled for new Flagler College Library from the current 112 to 500 seats. such as the Internet. Students will be able ByW. DEREK PARKER Abare noted that many libraries are to access the network, for example, Gargoyle Editor in Chief known as Learning Resource Centers. "We through the use of a Gopher, an elec are hoping ours will also be a complete tronic research aid which searches the Flagler College marks another mile learning center. This facility will be very network using key words or phrases. stone on Sept. 23 when groundbreaking conducive to learning," Abare added. According to Flagler College Presi ceremonies are held at Sevilla and Valencia The new facilities will include offices, dent William Proctor, the building of the Streets for its new $7.4 million library. The a computer center, seminar rooms, a gal- new library is another important step taken n·ame of the new library will be announced -lery and a lecture hall. by the college, ranking in importance at this ceremony. Demolition of pre-exist The new lecture hall does not imply with the college founding, accreditation, ing structures on the site took place on larger classes, however. According to Abare and the renovation of Kenan Hall. -

My Home in the Field of Honor

My Home In The Field of Honor Frances Wilson Huard Project Gutenberg's My Home In The Field of Honor, by Frances Wilson Huard This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: My Home In The Field of Honor Author: Frances Wilson Huard Release Date: April 28, 2004 [EBook #12185] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MY HOME IN THE FIELD OF HONOR *** Produced by Sean Pobuda MY HOME IN THE FIELD OF HONOUR BY FRANCES WILSON HUARD I The third week in July found a very merry gathering at the Chateau de Villiers. (Villiers is our summer home situated near Marne River, sixty miles or an hour by train to Paris.) Nothing, I think, could have been farther from thoughts than the idea of war. Our May Wilson Preston, the artist; Mrs. Chase, the editor of a well-known woman's magazine; Hugues Delorme, the French artist; and numerous other guests, discussed the theatre and the "Caillaux case" from every conceivable point of view, and their conversations were only interrupted by serious attempts to prove their national superiority at bridge, and long delightful walks in the park. As I look back now over those cheerful times, I can distinctly remember one bright sunny morning, when after a half-hour's climbing we reached the highest spot on our property. -

View from the Bridge:Formatted

A View from the Bridge A Play in Two Acts Characters Act One Louis Mike Alfieri The street and house front of a tenement building. The front is skeletal Eddie entirely. The main acting area is the living room–din ing room of Eddie’s Catherine apartment. It is a worker’s flat, clean, sparse, homely. There is a rocker Beatrice down front; a round dining table at center, with chairs; and a portable Marco phonograph. To ny At back are a bedroom door and an opening to the kitchen; none of these Rodolpho interiors are seen. First Immigration Officer Second Immigration Officer At the right, forestage, a desk. This is Mr Alfieri’s law office. There is Mr Lipari also a telephone booth. This is not used until the last scenes, so it may be Mrs Lipari covered or left in view. Two ‘Submarines’ A stairway leads up to the apartment, and then farther up to the next story, Neighbours which is not seen. Ramps, representing the street, run upstage and off to right and left. As the curtain rises, Louis and Mike, longshoremen, are pitching coins against the building at left. A distant foghorn blows. Enter Alfieri, a lawyer in his fifties turning gray; he is portly, good- humored, and thoughtful. The two pitchers nod to him as he passes. He crosses the stage to his desk, removes his hat, runs his fingers through his hair, and grinning, speaks to the audience. Alfieri You wouldn’t have known it, but something amusing has just happened. You see how uneasily they nod to me? That’s because I am a lawyer. -

Sheryl Crow's Tuesday Night Music Club

SHERYL CROW’S TUESDAY NIGHT MUSIC CLUB - DELUXE EDITION ADDS CD OF PREVIOUSLY UNRELEASED TRACKS AND OTHER RARITIES PLUS DVD OF CLASSIC VIDEOS AND A NEW TOUR DOCUMENTARY TO ONE OF ROCK’S MOST POPULAR ALBUMS The spectacular debut album that launched Sheryl Crow into rock music consciousness has been expanded both musically and visually for the 2CD/1DVD Tuesday Night Music Club – Deluxe Edition (A&M/UMe), released November 17, 2009. Along with the original 1993 album, the package adds a second CD containing B- sides, rarities and out-takes, as well as a bonus DVD featuring the album’s videos (“Leaving Las Vegas,” “All I Wanna Do,” “Strong Enough,” “Can’t Cry Anymore,” “Run, Baby, Run” and “What I Can Do For You,” plus a rare alternate version of “All I Wanna Do” directed by Roman Coppola) and a newly produced documentary comprised of on-the-road, backstage, soundcheck and live footage from the original album tour. Highlighting the bonus CD for Tuesday Night Music Club – Deluxe Edition are four previously unreleased recordings from 1995 that were intended for the follow-up album--“Coffee Shop,” “Killer Life,” “Essential Trip Of Hereness” and “You Want More” --each only now mixed by original Tuesday Night Music Club producer Bill Bottrell. In addition, Bottrell remixed the album’s “I Shall Believe” specifically for this Deluxe Edition. The bonus CD also includes a trio of U.K. single B-sides (“Reach Around Jerk,” an alternate “The Na-Na Song” titled “Volvo Cowgirl 99” and a cover of Eric Carmen’s “All By Myself”), a tribute album cover of Led Zeppelin’s “D’yer Mak’er,” and “On The Outside,” a contribution to an X-Files soundtrack album.