An Introduction to Timber Framing Learning This Traditional Method Begins with the Mortise-And-Tenon Joint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carpenters of Japanese Ancestry in Hawaii Hisao Goto Kazuko

Craft History and the Merging of Tool Traditions: Carpenters of Japanese Ancestry in Hawaii Hisao Goto Kazuko Sinoto Alexander Spoehr For centuries the Japanese have made extensive use of wood as the main raw material in the construction of houses and their furnishings, temples, shrines, and fishing boats. As a wood-worker, the carpenter is one of the most ancient of Japanese specialists. He developed a complex set of skills, a formidable body of technical knowledge, and a strong tradition of craftsmanship to be seen and appreciated in the historic wood structures of contemporary Japan.1 The first objective of this study of carpenters of Japanese ancestry in Hawaii is to throw light on how the ancient Japanese craft of carpentry was transplanted from Japan to a new social, cultural, and economic environment in Hawaii through the immigration of Japanese craftsmen and the subsequent training of their successors born in Hawaii. Despite its importance for the understanding of economic growth and develop- ment, the craft history of Hawaii has not received the attention it deserves. The second objective of the study is more anthropological in nature and is an attempt to analyze how two distinct manual tool traditions, Japanese and Western, met and merged in Hawaii to form a new composite tool tradition. This aspect of the study falls in a larger field dealing with the history of technology and of tool traditions in general. Carpentry today, both in Japan and in the United States, relies heavily on power rather than hand tools. Also, carpenters tend to be specialized, and construction is to a major degree a matter of assembling prefabricated parts. -

Sustainable Trail Bridge Design

U.S. Department of Transportation United States Department of Agriculture Federal Highway Administration Sustainable Trail Bridge Design Forest National Technology & 2023–2805P–NTDP March 2020 Service Development Program 2300–Recreation Sustainable Trail Bridge Design Notice Ordering Information This document was produced in cooperation with You can order a copy of this document using the the Recreational Trails Program of the U.S. Depart- order form on FHWA’s Recreational Trails Program ment of Transportation’s Federal Highway Adminis- website <http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/rec- tration in the interest of information exchange. The reational_trails/publications/trailpub.cfm> U.S. Government assumes no liability for the use of Fill out the order form and submit it electronically. information contained in this document. Or you may email your request to: [email protected] The U.S. Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers’ names Or you may mail your request to: appear in this report only because they are consid- Szanca Solutions/FHWA PDC ered essential to the objective of this document. 700 North 3rd Avenue The contents of this report reflect the views of the Altoona, PA 16601 authors, who are responsible for the facts and Fax: 814–239–2156 accuracy of the data presented herein. The con- tents do not necessarily reflect the official policy of Produced by the U.S. Department of Transportation. This report USDA Forest Service does not constitute a standard, specification, or National Technology and Development Program regulation. 5785 Hwy. 10 West Missoula, MT 59808–9361 Phone: 406–329–3978 Fax: 406–329–3719 Email: [email protected] U.S. -

Timber Planking, Puncheon and Boardwalk Structures

California State Parks Trails Handbook Chapter 15. Timber Planking, Puncheons, and Boardwalks ................................. 15-1 15.1. Best Management Practices ....................................................................... 15-2 15.2. Timber Planking .......................................................................................... 15-2 15.2.1. Applications ............................................................................................ 15-2 15.2.2. Construction ........................................................................................... 15-3 15.3. Puncheons ................................................................................................... 15-4 15.3.1. Applications ............................................................................................ 15-4 15.3.2. Construction ........................................................................................... 15-9 15.3.3. Curved Puncheons ............................................................................... 15-26 15.3.3.1. Parallel Mudsills ........................................................................... 15-31 15.3.3.2. Flared Mudsills ............................................................................. 15-31 15.3.4. Equestrian Puncheons.......................................................................... 15-32 15.4. Boardwalks ................................................................................................ 15-35 15.4.1. Applications ......................................................................................... -

Bows, Arrows, Vanes and Arrow Components • Finish: Realtree • � Peak Drawweight: 50,60,70Lbs

BOWS AVAILABLE BY PRO SHOP SHOWROOM SALES ONLY The following bows are available at our Pro Shop location. By Manufacturer’s Agreement, these bows are not available for mail order or wholesale distribution. Complete Lancaster Archery Compound Bow Accessory Packages Add to any Bow Purchase for $119 (A $179.59 Value!) Package Includes: • TruGlo 3 Pin Sight with Light • TruGlo 4-Arrow Loc Down Quiver • 5 Complete Stock Carbon Arrows (Includes Nocks, Points, and Fletching) • Trophy Ridge Quick Shot Whisker Biscuit Rest • CR Braided Bow Sling • Outer Limit Buzz Kill Stabilizer • Rubber String Silencers • Tru Glo Accessory Kit (Red) Silencers, D-loop Material, Peep, Kisser 2770010 2015 COMPOUND BOWS + Bear® Arena 30 + Bear® Color Kits + Bear® Bounty RTH Package + Bear® Cruzer RTH Package • Axle to Axle: 30 1/2” • Colors to Customize your Bear® Bow! • Axle to Axle: 29 3/4” • Axle to Axle: 32” • IBO Speed: 345 fps • Designed for: Motive, Empire, Agenda, Venue, • IBO Speed: 295 fps • IBO Speed: 310 fps • Brace Height: 6.5” Anarchy HC Rumor and Arena • Brace Height: 7” • Brace Height: 6.5” • Let Off: 75% • Kit Includes: Overmold Grip Panel Grips • Let Off: 80% • Let Off: 70% • Mass Weight: 3.8 lbs. (4) Arena Riser Inserts • Mass Weight: 3.2 lbs. • Mass Weight: 3.6 lbs. • Draw Length: 25 1/2-30” (2) Agenda and Venue Riser Inserts • Draw Length: 23 1/2-27” • Draw Length: 12-30” • Peak Draw Weight: 50, 60, 70 lbs. • Peak Draw Weight: 50 lbs. • Peak Draw Weight: 5-70 lbs. (2) String Dampeners Bows, Arrows, Vanes and Arrow Components Bows, Arrows, Vanes • Available RH and LH • Available Colors: Green Orange Red Yellow • Available RH and LH • Available RH and LH • Finish: Realtree Xtra® Green Camo • Finish: Realtree MAX-1® Camo • Finish: Realtree Xtra® Camo 1360213 $24.99 ea. -

FOSS® Materials and Motion Module Vocabulary/Glossary Terms NGSS Edition © 2018

FOSS® Materials and Motion Module Vocabulary/Glossary Terms NGSS Edition © 2018 Investigations Guide Vocabulary Investigation 1: Getting to Know Wood texture above tree absorb waterlogged basswood wood bead up woodworker below break Investigation 2: Getting to Know Paper cedar around change bend communicate blot compare bumpy different cardboard evaporate chipboard fewer construction paper float corner glue corrugated paper grain crease graph drop laminate dry layer facial tissue less fiber material flat mixture flip more flour observe fold particleboard half pine kraft paper plywood mold property newsprint raft over rough paper same paper towel sand papier-mâché sandpaper pulp sawdust recycling screen rolling senses slick shape stiff shavings strip sink submerge smooth tagboard soak tear spread thick strong thin test waxed paper FOSS Materials and Motion Module Vocabulary/Glossary Terms, NGSS Edition © 2018 1 of 3 wet motion wheat paste move pull Investigation 3: Getting to Know Fabric push burlap rocket cloth roll cold rolling conserve ramp corduroy slope denim slowly fabric speed fleece strength hot stop knit least magnet most natural resource nubby recycle reuse ripstop nylon rough satin scratchy seersucker shiny slippery smooth soak soft sparkle organza structure temperature terry cloth texture thread warp waterproof weft woven Investigation 4: Getting Things to Move cause collide collision direction distance effect fast gentle gravity FOSS Materials and Motion Module Vocabulary/Glossary Terms, NGSS Edition © 2018 2 of 3 Science Resources Vocabulary Investigation 1: Getting to Know Wood compare engineer forest observation tree wood Investigation 2: Getting to Know Paper paper pulp sawdust water Investigation 3: Getting to Know Fabric air fabric jute land oil recycle Investigation 4: Getting Things to Move collide direction gravity motion pull push rolling slope speed FOSS Materials and Motion Module Vocabulary/Glossary Terms, NGSS Edition © 2018 3 of 3 . -

Garage Doors by Ryterna EN

GARAGE DOORS by RYTERNA 2 GARAGE DOORS BY RYTERNA Content: 6 RIB 8 MIDRIB 12 FLUSH 14 GEORGIAN (CASSETTE) 16 SLICK 20 SLICK PLUS 22 MACRORIB & MICRORIB 24 TOPRIB 26 SLIM LINE 28 OKOUME 30 ALUMAX 32 RETRO 34 SIDE HINGED GARAGE DOORS 40 SIDE DOORS 44 WICKET DOORS 46 DECOR APPLIQUÉS 48 FULL VISION PANELS 49 STAINLESS STEEL WINDOWS 49 PVC DOUBLE GLAZED WINDOWS 51 HARDWARE TYPE R40 53 HARDWARE TYPE TL 54 FASCIA PANELS AND FRAMES 55 ACCESSORIES 56 THE SIDE SLIDING SECTIONAL DOOR 60 CUSTOM MADE DOORS DINE NI SO 9001 :2 00 0 ZN: 15 1 00 9 56 5 62 NON-STANDARD SOLUTIONS 62 MATCHING DESIGN GARAGE DOORS BY RYTERNA 3 Sectional door TL Alumax. Entrance door RD 80 custom design. 4 GARAGE DOORS BY RYTERNA Unlimited creativity Think outside the box GARAGE DOORS BY RYTERNA 5 Rib Horizontal ribs every 10 cm give this door a light robust appearance. This is a contemporary door that looks good in any architectural setting. ‘Rib’ design doors are often combined with full-vision aluminium panels available in any RAL colour. The Wood Rib style doors come with woodgrain embossed surface. ‘Rib’ design panels are best for extra size doors – they can be made up to 10 metres wide. Other painted colours similar to RAL palette Woodgrain Stucco 6 GARAGE DOORS BY RYTERNA RAL 9016 RAL 8017 Track type R40 UM/ SM/ TM, TL STD/ LHR FM/ LHR RM GARAGE DOORS BY RYTERNA 7 Midrib ‘Midrib’ design doors, grooved in the middle of each panel, give the impression of solid timber boards. -

FOSS Materials in Our World Module Glossary 3 Edition © 2012 Above In

FOSS Materials in Our World Module Glossary 3rd Edition © 2012 above in a higher place; on top of (IG) absorb to soak in (IG) across to or on the opposite side (IG) air a mixture of gases that we breathe (SRB) around to move or place along the outside (IG) basswood a lightweight, soft wood from a linden tree (IG) bead a small rounded object with a hole through which thread can be passed; a piece of jewelry (IG) below in a lower place; underneath (IG) bend to curve (IG) blot to dry or remove a liquid with an absorbent material, such as a paper towel (IG) break to separate into pieces (IG) bumpy having raised, rounded spots; lumpy (IG) burlap a strong, coarsely woven cloth made of fibers of jute, flax, or hemp (IG) cedar a soft wood from a cedar tree (IG) change to make or become different (IG) chipboard a thick, crude paper made from recycled cardboard (IG) clean washed or polished; not dirty (IG) cloth fabric or material formed by weaving or knitting (IG) clothing garments made of fabric to cover oneself (IG) communicate to explain or exchange thoughts and information, such as when writing or speaking (IG) compare to look at how things are the same and different (SRB, IG) construction paper a thicker paper that is many sizes and colors (IG) conserve to use wisely (IG) FOSS Materials in Our World Module Vocabulary/Glossary Terms, 3rd Edition © 2012 1 of 7 corduroy a durable fabric, usually made of cotton, with vertical ribs (IG) corner the point at which the sides of an object, such as a box, meet (IG) cornstarch a white powder made from -

Working-Class Router Table Easy-To-Build Table Is About Results, Not Appearances

Working-Class Router Table Easy-to-build table is about results, not appearances BY MARC ADAMS 60 FINE WOODWORKING COPYRIGHT 2014 by The Taunton Press, Inc. Copying and distribution of this article is not permitted. router table is indispensable for a wide range of tasks. in it; or a simple table-insert plate with a router screwed to it. Armed with a big, solid fence, it can cut joinery, raise Whatever you choose, the plate should be 3⁄8 in. to 1⁄2 in. thick A panels, produce moldings, and even edge-joint boards. and made from a material like aluminum or phenolic that won’t Take off the fence and the table can be used for pattern routing. sag from the weight of a big router. I went with the insert plate, I designed and built this router table years go, when I needed attaching a router I already own, a more affordable approach something fast and simple. I always figured I’d replace it some than buying a lift. day with something nicer. But nearly 30 years later, the original You’ll also need a simple plastic dust port designed for router table is still in use at my school, and we have built seven more fences, and some 1⁄4–20 threaded knobs and T-nuts for attaching just like it. That’s because the materials are affordable, the joinery the fence. If you don’t have a tool-triggered shop vacuum, I also is straightforward, the table is accurate, and it has all the features recommend a double switch made for router tables, like the one we require. -

Building a Sliding Table for Your Tablesaw

BUILDING A SLIDING TABLE FOR YOUR TABLESAW Safety Tablesaws can hurt you two ways. Involuntary injury is where the saw reaches out and touches you; it is almost always the result of kickback. The sliding table can virtually eliminate the risk of kickback during crosscutting by keeping your work A Sliding Crosscut Table is one of the most useful firmly under control, moving precisely in the plane of the blade. accessories you can add to your tablesaw. With good outfeed Voluntary injury happens when you reach out and touch support and an accurate crosscutting system, your saw will be as the blade, whether through inattention or distraction. Reducing safe, accurate and versatile as any in the business. the opportunity for voluntary injury is the job of our Lexan blade Building our sliding table is easy. The list of tools & materi- path cover, stop block, exit block, and the table's handle. The als you'll need is quite short: blade cover, unlike some saw guards, doesn't get in your way, obscure visibility or make it difficult to carry out a cut. It cannot One pair phenolic runners, included in kit absolutely prevent injury; if your workpiece can reach the blade, One Lexan blade path cover, included so can you if you try hard enough. However, it will prevent your 1/2" or 3/4" plywood 32-3/8" deep by 37" wide hands' easy access to the blade, and it will keep chips and saw- Plywood or hardwood 8" x 49" x 1-1/2" thick dust from smacking you in the face too. -

Download FMSTB Booklet in Pdf Format Now!

Fox Maple School of Traditional Building Timber Framing Natural Building Systems Traditional Design It would be part of my scheme of physical education that every youth in the state should learn to do something finely and thoroughly with his hand, so as to let him know what touch meant…Let him once learn to take a straight shaving off a plank, or draw a fine curve without faltering, or lay a brick up level in its mortar; and he has learned a multitude of other matters… —John Ruskin Contents Introduction to the School Site ..................................... 4 History & Mission ........................................................... 5 The Office Headquarters................................................ 8 The Library ................................................................... 12 The Dining Hall.............................................................16 The Workshop .............................................................. 18 New School Site, pg. 4 The Site Plan................................................................. 21 Timber Framing Courses .............................................. 22 A Workshop Primer .......................................................23 So You Want to be a Timber Framer? ..........................23 Timber Framing, pg. 22 What to bring & What to Expect ................................. 23 Timber Framing Tools ................................................... 25 A Beginner’s Tool Box ................................................. 25 Additional Supplies .......................................................28 -

You Can Build Your Next Project with Lumber That Will Never Decay, Crack, Warp, Or Need fi Nishing

How GOOD is Plastic WOOD? You can build your next project with lumber that will never decay, crack, warp, or need fi nishing. By Asa Christiana hree years ago I resurfaced my deck signs of damage from moisture, mold, material from a local supplier. But if you Twith composite boards made from sunlight, and insects. And there’s more want small orders or shorter material recycled plastic and wood dust. Although good news too: You can build almost shipped to you, it can be challenging to I live in the rainy Northwest, a giant Petri anything with plastic lumber, using the nd a supplier. See the Buyer’s Guide dish for moss and mold, the deck still same power and hand tools you already on p. 70 for some recommendations. looks as good as the day I installed it. And own. But there are important consid- the only maintenance I’ve done is a yearly erations you’ll need to make when scrub with soap and water. switching from real wood to plastic. I’ll fastFACTS at got me thinking about using go over some useful tips about cutting, • All plastic lumber except for PVC is synthetic lumber for other outdoor shaping, and joining the material. made with 95% recycled material. projects. It took a while, but I tried out Even though plastic lumber is made • Most plastic lumber is the main types of plastic lumber shown almost entirely from bottles, bags, and warrantied against weather here—everything from decking boards other products rescued from the waste damage for 20+ years. -

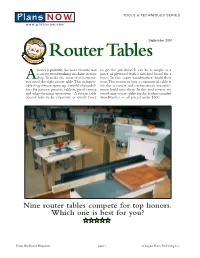

Veritas Router Table Review

TOOLS & TECHNIQUES SERIES Plans NOW® www.plansnow.com RKBE September 2001 O NC W H ® A W A R D Y IT E O L D F Q UA IT Router Tables O Router Tables R ’S CHOICE router is probably the most versatile and to get the job done. It can be as simple as a accurate woodworking machine in your piece of plywood with a notched board for a Ashop.To make the most of it, however, fence. In fact, many woodworkers build their you need the right router table.This indispen- own.The reason to buy a commercial table is sible shop fixture opens up a world of possibil- for the accuracy and conveniences manufac- ities for joinery, grooves, rabbets, panel raising turers build into them. In this tool review, we and edge-forming operations. A router table tested nine router tables for the budget-minded doesn’t have to be expensive or overly fancy woodworker — all priced under $300. Nine router tables compete for top honors. Which one is best for you? From Workbench Magazine page 1 © August Home Publishing Co. WHAT’S IMPORTANT baseplate that fits into a rabbeted to keep air circulating through it. All router tables aren’t created equal. recess in the top. Baseplates make bit- FEATURES. Many router table We found some significant differences changing easier, especially if you’re manufacturers offer quite an array of in several key aspects.We’ll talk about using a plunge router in your table. optional accessories that you can use those in a minute when we get to the They also make it easier to mount to customize your table.