The Contribution of Maame Afua Abasa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghana Gazette

GHANA GAZETTE Published by Authority CONTENTS PAGE Facility with Long Term Licence … … … … … … … … … … … … 1236 Facility with Provisional Licence … … … … … … … … … … … … 201 Page | 1 HEALTH FACILITIES WITH LONG TERM LICENCE AS AT 12/01/2021 (ACCORDING TO THE HEALTH INSTITUTIONS AND FACILITIES ACT 829, 2011) TYPE OF PRACTITIONER DATE OF DATE NO NAME OF FACILITY TYPE OF FACILITY LICENCE REGION TOWN DISTRICT IN-CHARGE ISSUE EXPIRY DR. THOMAS PRIMUS 1 A1 HOSPITAL PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI KUMASI KUMASI METROPOLITAN KPADENOU 19 June 2019 18 June 2022 PROF. JOSEPH WOAHEN 2 ACADEMY CLINIC LIMITED CLINIC LONG TERM ASHANTI ASOKORE MAMPONG KUMASI METROPOLITAN ACHEAMPONG 05 October 2018 04 October 2021 MADAM PAULINA 3 ADAB SAB MATERNITY HOME MATERNITY HOME LONG TERM ASHANTI BOHYEN KUMASI METRO NTOW SAKYIBEA 04 April 2018 03 April 2021 DR. BEN BLAY OFOSU- 4 ADIEBEBA HOSPITAL LIMITED PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG-TERM ASHANTI ADIEBEBA KUMASI METROPOLITAN BARKO 07 August 2019 06 August 2022 5 ADOM MMROSO MATERNITY HOME HEALTH CENTRE LONG TERM ASHANTI BROFOYEDU-KENYASI KWABRE MR. FELIX ATANGA 23 August 2018 22 August 2021 DR. EMMANUEL 6 AFARI COMMUNITY HOSPITAL LIMITED PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI AFARI ATWIMA NWABIAGYA MENSAH OSEI 04 January 2019 03 January 2022 AFRICAN DIASPORA CLINIC & MATERNITY MADAM PATRICIA 7 HOME HEALTH CENTRE LONG TERM ASHANTI ABIREM NEWTOWN KWABRE DISTRICT IJEOMA OGU 08 March 2019 07 March 2022 DR. JAMES K. BARNIE- 8 AGA HEALTH FOUNDATION PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI OBUASI OBUASI MUNICIPAL ASENSO 30 July 2018 29 July 2021 DR. JOSEPH YAW 9 AGAPE MEDICAL CENTRE PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI EJISU EJISU JUABEN MUNICIPAL MANU 15 March 2019 14 March 2022 10 AHMADIYYA MUSLIM MISSION -ASOKORE PRIMARY HOSPITAL LONG TERM ASHANTI ASOKORE KUMASI METROPOLITAN 30 July 2018 29 July 2021 AHMADIYYA MUSLIM MISSION HOSPITAL- DR. -

Ghana Poverty Mapping Report

ii Copyright © 2015 Ghana Statistical Service iii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Ghana Statistical Service wishes to acknowledge the contribution of the Government of Ghana, the UK Department for International Development (UK-DFID) and the World Bank through the provision of both technical and financial support towards the successful implementation of the Poverty Mapping Project using the Small Area Estimation Method. The Service also acknowledges the invaluable contributions of Dhiraj Sharma, Vasco Molini and Nobuo Yoshida (all consultants from the World Bank), Baah Wadieh, Anthony Amuzu, Sylvester Gyamfi, Abena Osei-Akoto, Jacqueline Anum, Samilia Mintah, Yaw Misefa, Appiah Kusi-Boateng, Anthony Krakah, Rosalind Quartey, Francis Bright Mensah, Omar Seidu, Ernest Enyan, Augusta Okantey and Hanna Frempong Konadu, all of the Statistical Service who worked tirelessly with the consultants to produce this report under the overall guidance and supervision of Dr. Philomena Nyarko, the Government Statistician. Dr. Philomena Nyarko Government Statistician iv TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ............................................................................. iv LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ -

Small and Medium Forest Enterprises in Ghana

Small and Medium Forest Enterprises in Ghana Small and medium forest enterprises (SMFEs) serve as the main or additional source of income for more than three million Ghanaians and can be broadly categorised into wood forest products, non-wood forest products and forest services. Many of these SMFEs are informal, untaxed and largely invisible within state forest planning and management. Pressure on the forest resource within Ghana is growing, due to both domestic and international demand for forest products and services. The need to improve the sustainability and livelihood contribution of SMFEs has become a policy priority, both in the search for a legal timber export trade within the Voluntary Small and Medium Partnership Agreement (VPA) linked to the European Union Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (EU FLEGT) Action Plan, and in the quest to develop a national Forest Enterprises strategy for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD). This sourcebook aims to shed new light on the multiple SMFE sub-sectors that in Ghana operate within Ghana and the challenges they face. Chapter one presents some characteristics of SMFEs in Ghana. Chapter two presents information on what goes into establishing a small business and the obligations for small businesses and Ghana Government’s initiatives on small enterprises. Chapter three presents profiles of the key SMFE subsectors in Ghana including: akpeteshie (local gin), bamboo and rattan household goods, black pepper, bushmeat, chainsaw lumber, charcoal, chewsticks, cola, community-based ecotourism, essential oils, ginger, honey, medicinal products, mortar and pestles, mushrooms, shea butter, snails, tertiary wood processing and wood carving. -

Sefwi Bibiani-Anhwiaso- Bekwai District

SEFWI BIBIANI-ANHWIASO- BEKWAI DISTRICT Copyright (c) 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country’s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the Sefwi Bibiani-Anhwiaso-Bekwai District is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence-based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

Bekwai Municipal Assembly Annual Progress Report 2017

BEKWAI MUNICIPAL ASSEMBLY ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS PAGE CHAPTER ONE 1.0 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………...1 1.1 PURPOSE OF MONITORING AND EVALUATION…………………………………..2 1.2 PROCESSES INVOLVED…………………………………. …………………….……..2 1.3 PROBLEMS ENCOUNTED……..…………………………………………………….…1 1.4 STATUS OF IMPLEMENTATION OF THE MTDP 2014-2017..……………..…….….3 1.4.1 STATUS OF IMPLEMENTATION OF THE ANNUAL ACTION PLAN 2017….........4 1.5 SUMMARY OF ACHIEVEMENTS AND CHALLENGES WITH THE IMPLEMENTATION OF BMA‟s MTDP…………………………………………………………………………..….….5 CHAPTER TWO 2.0 MONITORING AND EVALUATION ACTIVITIES REPORT………………………............34 2.1 PROGRAMMES/PROJECTS IMPLEMENTATION STATUS FOR 2017………..…….....34 2.2 Revenue and Expenditure Performance of the Bekwai Municipality 2014-2017…...………44 2.2.1 REVENUE PERFORMANCE 2014-2017……………………………….…….……….....45 2.2.2 EXPENDITURE PERFORMANCE 2014-2017………………………………….….…....48 2.3 UPDATE ON NATIONAL INDICATORS, MUNICIPAL INDICATORS AND TARGETS......................................................................................................................................51 2.3.1 COMMENTS ON THE CORE INDICATORS…………………………………….……..54 2.4 Education…………………………………………………………………………….……....57 2.5 HEALTH ……………………………………………………………………………………63 2.6 WATER AND SANITATION……............................………………………....……………69 2.6.1 SANITATION……………………………………………………………………….…….70 2.6.2 WASTE MANAGEMENT –TREATMENT………………………………………….…..70 2.6.3 LANDFILL MANAGEMENT……………………………………………………………70 2.6.4 LIQUID WASTE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM…………………………………………..71 -

Greater Accra Region

NATIONAL COMMUNICATIONS AUTHORITY LIST OF AUTHORISED VHF-FM RADIO STATIONS IN GHANA AS AT FOURTH QUARTER, 2013 Last updated on the 30th December, 2013 1 NATIONAL COMMUNICATIONS AUTHORITY LIST OF FM STATIONS IN THE COUNTRY AS AT FOURTH QUARTER, 2013 NO. NAME OF TOTAL NO. PUBLIC COMMUN CAMPUS COMMER TOTAL TOTAL REGIONS AUTHORIS ITY CIAL NO. IN NO. NOT ED OPERATI IN ON OPERATI ON 1. Greater Accra 47 5 6 3 33 42 5 2. Ashanti 47 3 4 2 38 41 6 3. Brong Ahafo 45 3 4 0 38 38 7 4. Western 52 6 4 1 39 37 15 5. Central 27 2 7 3 15 22 5 6. Eastern 29 2 5 1 21 26 3 7. Volta 34 3 7 1 23 24 10 8. Northern 30 7 10 0 13 20 10 9. Upper East 13 2 3 1 7 10 3 10. Upper West 15 3 8 1 3 7 8 Total 339 36 58 13 232 267 74 Last updated on the 30th December, 2013 2 GREATER ACCRA REGION S/N Name and Address of Date of Assigned On Air Not Location (Town Type of Station Company Authorisation Frequency on Air /City) 1. MASCOTT MULTI- 13 – 12 – 95 87.9MHz On Air Accra Commercial FM SERVICES LIMITED. (ATLANTIS RADIO) Box PMB CT 106, Accra Tel: 0302 7011212/233308 Fax:0302 230871 Email: 2. NETWORK 7 - 09 – 95 90.5MHz On Air Accra Commercial FM BROADCASTING LIMITED (RADIO GOLD) Box OS 2723,OSU Accra Tel:0302-300281/2 Fax: 0302-300284 Email:[email protected] m 3. -

Electoral Commission of Ghana List of Registered Voters - 2006

Electoral Commission of Ghana List of Registered voters - 2006 Region: ASHANTI District: ADANSI NORTH Constituency ADANSI ASOKWA Electoral Area Station Code Polling Station Name Total Voters BODWESANGO WEST 1 F021501 J S S BODWESANGO 314 2 F021502 S D A PRIM SCH BODWESANGO 456 770 BODWESANGO EAST 1 F021601 METH CHURCH BODWESANGO NO. 1 468 2 F021602 METH CHURCH BODWESANGO NO. 2 406 874 PIPIISO 1 F021701 L/A PRIM SCHOOL PIPIISO 937 2 F021702 L/A PRIM SCH AGYENKWASO 269 1,206 ABOABO 1 F021801A L/A PRIM SCH ABOABO NO2 (A) 664 2 F021801B L/A PRIM SCH ABOABO NO2 (B) 667 3 F021802 L/A PRIM SCH ABOABO NO1 350 4 F021803 L/A PRIM SCH NKONSA 664 5 F021804 L/A PRIM SCH NYANKOMASU 292 2,637 SAPONSO 1 F021901 L/A PRIM SCH SAPONSO 248 2 F021902 L/A PRIM SCH MEM 375 623 NSOKOTE 1 F022001 L/A PRIM ARY SCH NSOKOTE 812 2 F022002 L/A PRIM SCH ANOMABO 464 1,276 ASOKWA 1 F022101 L/A J S S '3' ASOKWA 224 2 F022102 L/A J S S '1' ASOKWA 281 3 F022103 L/A J S S '2' ASOKWA 232 4 F022104 L/A PRIM SCH ASOKWA (1) 464 5 F022105 L/A PRIM SCH ASOKWA (2) 373 1,574 BROFOYEDRU EAST 1 F022201 J S S BROFOYEDRU 352 2 F022202 J S S BROFOYEDRU 217 3 F022203 L/A PRIM BROFOYEDRU 150 4 F022204 L/A PRIM SCH OLD ATATAM 241 960 BROFOYEDRU WEST 1 F022301 UNITED J S S 1 BROFOYEDRU 130 2 F022302 UNITED J S S (2) BROFOYEDRU 150 3 F022303 UNITED J S S (3) BROFOYEDRU 289 569 16 January 2008 Page 1 of 144 Electoral Commission of Ghana List of Registered voters - 2006 Region: ASHANTI District: ADANSI NORTH Constituency ADANSI ASOKWA Electoral Area Station Code Polling Station Name Total Voters -

The Operationalization of the Dlrev Software for Improved Revenue Mobilization at Local Government Level: a Cost-Benefit Analysis

THE OPERATIONALIZATION OF THE DLREV SOFTWARE FOR IMPROVED REVENUE MOBILIZATION AT LOCAL GOVERNMENT LEVEL: A COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS GOVERNANCE FOR INCLUSIVE DEVELOPMENT / SUPPORT FOR DECENTRALISATION REFORMS (SFDR) DEUTSCHE GESELLSCHAFT FÜR INTERNATIONALE ZUSAMMENARBEIT (GIZ) GMBH NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT PLANNING COMMISSION COPENHAGEN CONSENSUS CENTER © 2020 Copenhagen Consensus Center [email protected] www.copenhagenconsensus.com This work has been produced as a part of the Ghana Priorities project. Some rights reserved This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution Please cite the work as follows: #AUTHOR NAME#, #PAPER TITLE#, Ghana Priorities, Copenhagen Consensus Center, 2020. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0. Third-party-content Copenhagen Consensus Center does not necessarily own each component of the content contained within the work. If you wish to re-use a component of the work, it is your responsibility to determine whether permission is needed for that re-use and to obtain permission from the copyright owner. Examples of components can include, but are not limited to, tables, figures, or images. PRELIMINARY DRAFT AS OF MAY 18, 2020 The operationalization of the dLRev software for improved revenue mobilization at local government level: a cost-benefit analysis Ghana Priorities Governance For Inclusive Development / Support for Decentralisation Reforms (SfDR), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH Copenhagen Consensus Center Academic Abstract Revenue mobilization and management are critical to local government service delivery. Whereas traditional practices emphasized personal interactions and manual record- keeping, geospatial data, internet and information networks have the power to streamline these municipal processes. -

District Analytical Report, Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly

KUMASI METROPOLITAN Copyright (c) 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country’s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the Kumasi Metropolitan is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence- based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

Bekwai Municipality

BEKWAI MUNICIPALITY Copyright © 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country‟s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the Bekwai Municipality is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence- based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

Church Directory for Ghana

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Stone-Campbell Books Stone-Campbell Resources 10-1-1980 Church Directory for Ghana World Bible School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/crs_books Part of the Africana Studies Commons, Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation World Bible School, "Church Directory for Ghana" (1980). Stone-Campbell Books. 591. https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/crs_books/591 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Stone-Campbell Resources at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Stone-Campbell Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. ~••,o CHURCH Dt:ECTORY for GHANA Give Africans The Gospel .. They'll Do Th~ Preaching! "'rT,,Tl"\T,T'T T"'T"\r"IT"'lfT"'ltT~r r\.l...,l\.1\U liLL.LJ\.JLi'iLH .l .J We are endebted to Bro. John Kesse and Bro. Samuel Obeng of Kumasi, Ghana, and to Bro. Ed Mosby our American missionary in Accra, Ghana for coordinating the information in this directory. It is suggested that all W.B.S. teachers notify their students of the information concerning the church nearest them, so they can go to the brethren for further instruc tion and baptism. It is not logical to expect the local preachers to contact the thousands of students, but the people can go to the brethren all over Ghana. The preachers in Ghana who were contacted were in accord with this plan and will give full cooperation. TIMES OF SERVICES: Most congregations in Ghana meet at 9:00 a.m. -

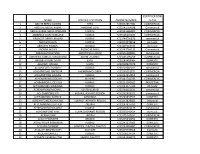

Name Specific Location Phone Number Certification Class

CERTIFICATION NAME SPECIFIC LOCATION PHONE NUMBER CLASS 1 ABAYIE BERKO AKWASI TEPA +233542854981 COMMERCIAL 2 ABDULAI ABDUL-RAZAK MABANG TEPA +233242764598 Commercial 3 ABDUL-KARIM ABDUL RAHMAN KUMASI +233243286809 COMMERCIAL 4 ABEBRESE DJAN ROWLAND KUMASI +233506264844 COMMERCIAL 5 ABOAGYE DANIEL AKWASI KUMASI +233244756870 commercial 6 ABOAGYE ELVIS KUMASI +233242978816 domestic 7 ABOAGYE KWAME BEKWAI +233207163334 domestic 8 ABORAH MOSES BUOHO KUMASI +233247764133 Commercial 9 ABRAHAM BOATENG AKROPONG KUMASI +233246188985 commercial 10 ABROKWA SAMUEL KORANTENG ADUM , KUMASI +233246590209 COMMERCIAL 11 ABUGRI AYAGRI DAVID EJISU +233249458064 DOMESTIC 12 ABUKARI INUSAH EJURA +233200937079 DOMESTIC 13 ACCOMFORD RICHARD KUMASI +233201682011 commercial 14 ACHEAMPONG BAFFOUR AHENEMAKOKOBEN +233248253831 COMMERCIAL 15 ACHEAMPONG AKWASI KUMASI +233242954852 commercial 16 ACHEAMPONG GIDEON MAAKRO +233241744743 COMMERCIAL 17 ACHEAMPONG JOE ELLIS KUMASI +233244560405 INDUSTRIAL 18 ACHEAMPONG KWABENA KUMASI +233243375366 domestic 19 ACHEAMPONG MICHAEL ASAFO-KUMASI +233244102431 commercial 20 ACHEAMPONG NTI KUMASI, ASHANTI REGION +233262428325 commercial 21 ACHEAMPONG PATRICK KONONGO +233249833553 DOMESTIC 22 ACHEAMPONG RICHMOND KUMASI ASHANTI REGION +233243828683 Industrial 23 ACHEAMPONG STEPHEN OBUASI +233247937033 DOMESTIC 24 ACHEAMPONG WILLIAM KUMASI +233203321176 commercial 25 ACHEAMPONG YAW KUMASI,ASHANTI REGION +233265042424 domestic 26 ACKAH JOHN OBUASI +233275247651 COMMERCIAL 27 ACKAH PADMORE BEKWAI +233245340252 DOMESTIC 28 ACKAH PHILIP