Live and Let Evolve the James Bond Titles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Sire Evaluation Database Results | National Association of Animal Breeders

12/7/2018 Sire Evaluation Database Results | National Association of Animal Breeders Sire Evaluation Database THE FOLLOWING SIRES MATCH THE SEARCH CRITERIA OF THE 50% FOR TRAIT: PTA MILK POUNDS Click on a registration number to get details about a particular sire. Breed Country Reg. Number Registration Name Primary NAAB Code PTA Milk PTA Milk Rank HO USA 000070726929 UECKER SUPERSIRE JOSUPER-ET 029HO17553 3442 1 HO USA 000071703339 BACON-HILL MONTROSS-ET 007HO12165 2910 2 HO 840 003008897582 S-S-I SNOWMAN MAYFLOWER-ET 007HO11621 2732 3 HO 840 003011816330 CO-OP PRINCETON-ET 001HO11881 2699 4 HO USA 000070372014 SULLY HARTFORD SWMN MYTH-ET 001HO10692 2698 5 HO 840 003125201993 S-S-I MONTROSS DUKE-ET 250HO13267 2570 6 HO USA 000072064184 PINE-TREE ALTABARK-ET 011HO11487 2569 7 HO CAN 000011857459 BRYCEHOLME BRODIE-ET 029HO17726 2557 8 HO CAN 000108251028 SNOWBIZ LITTLETON 200HO06637 2552 9 HO USA 000072850448 WEBB-VUE SPARK 2060-ET 007HO12418 2488 10 HO 840 003123886035 S-S-I MONTROSS JEDI-ET 007HO13250 2480 11 HO 840 003010356026 MR OAK DELCO 57279-ET 151HO00744 2458 12 HO USA 000069981344 SEAGULL-BAY SARGEANT-ET 147HO02424 2454 13 HO USA 000071451769 CO-OP DAY TWINKIE-ET 001HO11425 2422 14 HO USA 000071813417 DE-SU ALTALEAF-ET 011HO11478 2402 15 HO USA 000072128215 MR MOGUL DENVER 1426-ET 151HO00690 2365 16 HO USA 000071181765 SANDY-VALLEY JUMP START-ET 566HO01197 2336 17 HO USA 000072852032 DE-SU FERDINAND 12489-ET 007HO12611 2295 18 HO 840 003123885976 S-S-I MONTROSS JETT-ET 007HO13251 2280 19 HO USA 000071922001 CO-OP UPD GREATEST LIFELONG -

The James Bond Quiz Eye Spy...Which Bond? 1

THE JAMES BOND QUIZ EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 1. 3. 2. 4. EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 5. 6. WHO’S WHO? 1. Who plays Kara Milovy in The Living Daylights? 2. Who makes his final appearance as M in Moonraker? 3. Which Bond character has diamonds embedded in his face? 4. In For Your Eyes Only, which recurring character does not appear for the first time in the series? 5. Who plays Solitaire in Live And Let Die? 6. Which character is painted gold in Goldfinger? 7. In Casino Royale, who is Solange married to? 8. In Skyfall, which character is told to “Think on your sins”? 9. Who plays Q in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service? 10. Name the character who is the head of the Japanese Secret Intelligence Service in You Only Live Twice? EMOJI FILM TITLES 1. 6. 2. 7. ∞ 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10. GUESS THE LOCATION 1. Who works here in Spectre? 3. Who lives on this island? 2. Which country is this lake in, as seen in Quantum Of Solace? 4. Patrice dies here in Skyfall. Name the city. GUESS THE LOCATION 5. Which iconic landmark is this? 7. Which country is this volcano situated in? 6. Where is James Bond’s family home? GUESS THE LOCATION 10. In which European country was this iconic 8. Bond and Anya first meet here, but which country is it? scene filmed? 9. In GoldenEye, Bond and Xenia Onatopp race their cars on the way to where? GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 1. In which Bond film did the iconic Aston Martin DB5 first appear? 2. -

Proposed Acquisition

Proposed Acquisition February 9, 2018 THIS ANNOUNCEMENT AND THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN IS NOT FOR RELEASE, PUBLICATION OR DISTRIBUTION, IN WHOLE OR IN PART, DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY, IN OR INTO ANY JURISDICTION IN WHICH RELEASE, PUBLICATION OR DISTRIBUTION WOULD BE UNLAWFUL. PLEASE SEE THE IMPORTANT NOTICE AT THE END OF THIS ANNOUNCEMENT. 9 February 2018 Trinity Mirror plc Proposed acquisition of Northern & Shell's publishing assets Trinity Mirror plc ("Trinity Mirror" or the "Company") is pleased to announce the proposed acquisition of Northern & Shell's publishing assets for a total purchase price of £126.7 million. These comprise Northern & Shell Network Limited ("NSNL"), a subsidiary of Northern & Shell Media Group Limited containing the publishing assets of Northern & Shell and its subsidiaries, International Distribution 2018 Limited and a 50% equity interest in Independent Star Limited (the "Acquisition"). The purchase consideration of £126.7 million will be satisfied by the payment to the Northern & Shell Media Group Limited (the "Seller") of, in aggregate, an initial cash consideration of £47.7 million; deferred cash consideration of £59.0 million payable over 2020 - 2023; and the balance of £20.0 million by the issue to the Seller of 25,826,746 new ordinary shares of 10p each ("Consideration Shares"). Trinity Mirror will also make a one-off cash payment of £41.2 million to the Northern & Shell Pension Schemes and a recovery plan through to 2027 has been agreed with total payments of £29.2 million. Strong strategic rationale -

Track 1 Juke Box Jury

CD1: 1959-1965 CD4: 1971-1977 Track 1 Juke Box Jury Tracks 1-6 Mary, Queen Of Scots Track 2 Beat Girl Track 7 The Persuaders Track 3 Never Let Go Track 8 They Might Be Giants Track 4 Beat for Beatniks Track 9 Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland Track 5 The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair Tracks 10-11 The Man With The Golden Gun Track 6 Dr. No Track 12 The Dove Track 7 From Russia With Love Track 13 The Tamarind Seed Tracks 8-9 Goldfinger Track 14 Love Among The Ruins Tracks 10-17 Zulu Tracks 15-19 Robin And Marian Track 18 Séance On A Wet Afternoon Track 20 King Kong Tracks 19-20 Thunderball Track 21 Eleanor And Franklin Track 21 The Ipcress File Track 22 The Deep Track 22 The Knack... And How To Get It CD5: 1978-1983 CD2: 1965-1969 Track 1 The Betsy Track 1 King Rat Tracks 2-3 Moonraker Track 2 Mister Moses Track 4 The Black Hole Track 3 Born Free Track 5 Hanover Street Track 4 The Wrong Box Track 6 The Corn Is Green Track 5 The Chase Tracks 7-12 Raise The Titanic Track 6 The Quiller Memorandum Track 13 Somewhere In Time Track 7-8 You Only Live Twice Track 14 Body Heat Tracks 9-14 The Lion In Winter Track 15 Frances Track 15 Deadfall Track 16 Hammett Tracks 16-17 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Tracks 17-18 Octopussy CD3: 1969-1971 CD6: 1983-2001 Track 1 Midnight Cowboy Track 1 High Road To China Track 2 The Appointment Track 2 The Cotton Club Tracks 3-9 The Last Valley Track 3 Until September Track 10 Monte Walsh Track 4 A View To A Kill Tracks 11-12 Diamonds Are Forever Track 5 Out Of Africa Tracks 13-21 Walkabout Track 6 My Sister’s Keeper -

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'D Base Set 1 Harold Sakata As Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk As Mr

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'d Base Set 1 Harold Sakata as Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk as Mr. Ling Base Set 3 Andreas Wisniewski as Necros Base Set 4 Carmen Du Sautoy as Saida Base Set 5 John Rhys-Davies as General Leonid Pushkin Base Set 6 Andy Bradford as Agent 009 Base Set 7 Benicio Del Toro as Dario Base Set 8 Art Malik as Kamran Shah Base Set 9 Lola Larson as Bambi Base Set 10 Anthony Dawson as Professor Dent Base Set 11 Carole Ashby as Whistling Girl Base Set 12 Ricky Jay as Henry Gupta Base Set 13 Emily Bolton as Manuela Base Set 14 Rick Yune as Zao Base Set 15 John Terry as Felix Leiter Base Set 16 Joie Vejjajiva as Cha Base Set 17 Michael Madsen as Damian Falco Base Set 18 Colin Salmon as Charles Robinson Base Set 19 Teru Shimada as Mr. Osato Base Set 20 Pedro Armendariz as Ali Kerim Bey Base Set 21 Putter Smith as Mr. Kidd Base Set 22 Clifford Price as Bullion Base Set 23 Kristina Wayborn as Magda Base Set 24 Marne Maitland as Lazar Base Set 25 Andrew Scott as Max Denbigh Base Set 26 Charles Dance as Claus Base Set 27 Glenn Foster as Craig Mitchell Base Set 28 Julius Harris as Tee Hee Base Set 29 Marc Lawrence as Rodney Base Set 30 Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi Base Set 31 Lisa Guiraut as Gypsy Dancer Base Set 32 Alejandro Bracho as Perez Base Set 33 John Kitzmiller as Quarrel Base Set 34 Marguerite Lewars as Annabele Chung Base Set 35 Herve Villechaize as Nick Nack Base Set 36 Lois Chiles as Dr. -

28Apr2004p2.Pdf

144 NAXOS CATALOGUE 2004 | ALPHORN – BAROQUE ○○○○ ■ COLLECTIONS INVITATION TO THE DANCE Adam: Giselle (Acts I & II) • Delibes: Lakmé (Airs de ✦ ✦ danse) • Gounod: Faust • Ponchielli: La Gioconda ALPHORN (Dance of the Hours) • Weber: Invitation to the Dance ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Slovak RSO / Ondrej Lenárd . 8.550081 ■ ALPHORN CONCERTOS Daetwyler: Concerto for Alphorn and Orchestra • ■ RUSSIAN BALLET FAVOURITES Dialogue avec la nature for Alphorn, Piccolo and Glazunov: Raymonda (Grande valse–Pizzicato–Reprise Orchestra • Farkas: Concertino Rustico • L. Mozart: de la valse / Prélude et La Romanesca / Scène mimique / Sinfonia Pastorella Grand adagio / Grand pas espagnol) • Glière: The Red Jozsef Molnar, Alphorn / Capella Istropolitana / Slovak PO / Poppy (Coolies’ Dance / Phoenix–Adagio / Dance of the Urs Schneider . 8.555978 Chinese Women / Russian Sailors’ Dance) Khachaturian: Gayne (Sabre Dance) • Masquerade ✦ AMERICAN CLASSICS ✦ (Waltz) • Spartacus (Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia) Prokofiev: Romeo and Juliet (Morning Dance / Masks / # DREAMER Dance of the Knights / Gavotte / Balcony Scene / A Portrait of Langston Hughes Romeo’s Variation / Love Dance / Act II Finale) Berger: Four Songs of Langston Hughes: Carolina Cabin Shostakovich: Age of Gold (Polka) •␣ Bonds: The Negro Speaks of Rivers • Three Dream Various artists . 8.554063 Portraits: Minstrel Man •␣ Burleigh: Lovely, Dark and Lonely One •␣ Davison: Fields of Wonder: In Time of ✦ ✦ Silver Rain •␣ Gordon: Genius Child: My People • BAROQUE Hughes: Evil • Madam and the Census Taker • My ■ BAROQUE FAVOURITES People • Negro • Sunday Morning Prophecy • Still Here J.S. Bach: ‘In dulci jubilo’, BWV 729 • ‘Nun komm, der •␣ Sylvester's Dying Bed • The Weary Blues •␣ Musto: Heiden Heiland’, BWV 659 • ‘O Haupt voll Blut und Shadow of the Blues: Island & Litany •␣ Owens: Heart on Wunden’ • Pastorale, BWV 590 • ‘Wachet auf’ (Cantata, the Wall: Heart •␣ Price: Song to the Dark Virgin BWV 140, No. -

A Queer Analysis of the James Bond Canon

MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL May 2019 Copyright 2019 by Grant C. Hester ii MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester This dissertation was prepared under the direction of the candidate's dissertation advisor, Dr. Jane Caputi, Center for Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, Communication, and Multimedia and has been approved by the members of his supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Khaled Sobhan, Ph.D. Interim Dean, Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Jane Caputi for guiding me through this process. She was truly there from this paper’s incubation as it was in her Sex, Violence, and Hollywood class where the idea that James Bond could be repressing his homosexuality first revealed itself to me. She encouraged the exploration and was an unbelievable sounding board every step to fruition. Stephen Charbonneau has also been an invaluable resource. Frankly, he changed the way I look at film. His door has always been open and he has given honest feedback and good advice. Oliver Buckton possesses a knowledge of James Bond that is unparalleled. I marvel at how he retains such information. -

Northern & Shell Opportunities In-Print & Online Case Study

Northern & Shell Opportunities In-Print & Online Case Study – Millionaire Mansion In-Print Case Study – Millionaire Mansion Space of Newspapers/magazines Number of insertions magazine OK! Magazine – one week 1 x insertion Half page • N&S is the largest publisher of celebrity magazines with New! Magazine – one week 1 x insertion Half page 37% share of the market. 1 in 4 UK adults read an N&S press publication or visit their websites every month. Star Magazine – one week 1 x insertion Full page Daily Express 2 x insertions 17x3 • Only ONE prize is required and this gets repeated into all the titles in the table (to the right). We are the only Sunday Express – 1 day 1 x insertion 17x3 newspapers that offers this service and has the highest Daily Star 2 x insertions 10x4 total print reach out there. You will receive a total of 15 inserts for the one competition booking. Daily Star Sunday – 1 day 1 x insertion 10x4 • The competition pages are absolutely stunning. They Saturday Magazine (Daily Express) – also have a FREE entry route mechanism, so the entries 1 week 1 x insertion 1/2 page are always phenomenal. S Magazine (Sunday Express) – 1 • The competitions have fantastic brand presence and week 1 x insertion 1/2 page brand exposure. HOT TV Magazine (Daily Star) – • The MPV is £1000 (which can be shared between Tabloid size – 1 week 1 x insertion Full page multiple winners) TV! Life Magazine (Daily Star Sunday) – Tabloid size 1 week 1 x insertion 1/3 page Millionaire Mansion ran a £1,000 cash prize Competition for one lucky winner that ran from 21st January – 10th March 2018. -

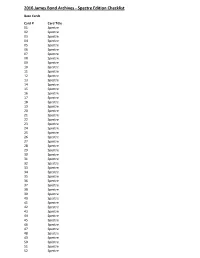

2016 James Bond Archives - Spectre Edition Checklist

2016 James Bond Archives - Spectre Edition Checklist Base Cards Card # Card Title 01 Spectre 02 Spectre 03 Spectre 04 Spectre 05 Spectre 06 Spectre 07 Spectre 08 Spectre 09 Spectre 10 Spectre 11 Spectre 12 Spectre 13 Spectre 14 Spectre 15 Spectre 16 Spectre 17 Spectre 18 Spectre 19 Spectre 20 Spectre 21 Spectre 22 Spectre 23 Spectre 24 Spectre 25 Spectre 26 Spectre 27 Spectre 28 Spectre 29 Spectre 30 Spectre 31 Spectre 32 Spectre 33 Spectre 34 Spectre 35 Spectre 36 Spectre 37 Spectre 38 Spectre 39 Spectre 40 Spectre 41 Spectre 42 Spectre 43 Spectre 44 Spectre 45 Spectre 46 Spectre 47 Spectre 48 Spectre 49 Spectre 50 Spectre 51 Spectre 52 Spectre 53 Spectre 54 Spectre 55 Spectre 56 Spectre 57 Spectre 58 Spectre 59 Spectre 60 Spectre 61 Spectre 62 Spectre 63 Spectre 64 Spectre 65 Spectre 66 Spectre 67 Spectre 68 Spectre 69 Spectre 70 Spectre 71 Spectre 72 Spectre 73 Spectre 74 Spectre 75 Spectre 76 Spectre Diamond Are Forever Throwback Cards (1:6 packs) Card # Card Title 01 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 02 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 03 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 04 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 05 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 06 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 07 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 08 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 09 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 10 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 11 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 12 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 13 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 14 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 15 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 16 Diamond Are Forever -

International Spy Museum

International Spy Museum Searchable Master Script, includes all sections and areas Area Location, ID, Description Labels, captions, and other explanatory text Area 1 – Museum Lobby M1.0.0.0 ΚΑΤΆΣΚΟΠΟΣ SPY SPION SPIJUN İSPİYON SZPIEG SPIA SPION ESPION ESPÍA ШПИОН Language of Espionage, printed on SCHPION MAJASUSI windows around entrance doors P1.1.0.0 Visitor Mission Statement For Your Eyes Only For Your Eyes Only Entry beyond this point is on a need-to-know basis. Who needs to know? All who would understand the world. All who would glimpse the unseen hands that touch our lives. You will learn the secrets of tradecraft – the tools and techniques that influence battles and sway governments. You will uncover extraordinary stories hidden behind the headlines. You will meet men and women living by their wits, lurking in the shadows of world affairs. More important, however, are the people you will not meet. The most successful spies are the unknown spies who remain undetected. Our task is to judge their craft, not their politics – their skill, not their loyalty. Our mission is to understand these daring professionals and their fallen comrades, to recognize their ingenuity and imagination. Our goal is to see past their maze of mirrors and deception to understand their world of intrigue. Intelligence facts written on glass How old is spying? First record of spying: 1800 BC, clay tablet from Hammurabi regarding his spies. panel on left side of lobby First manual on spy tactics written: Over 2,000 years ago, Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. 6 video screens behind glass panel with facts and images. -

British Media Coverage of the Press Reform Debate : Journalists Reporting Journalism

This is a repository copy of British media coverage of the press reform debate : journalists reporting journalism. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/165721/ Version: Published Version Book: Ogbebor, B. orcid.org/0000-0001-5117-9547 (2020) British media coverage of the press reform debate : journalists reporting journalism. Springer Nature , (227pp). ISBN 9783030372651 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ British Media Coverage of the Press Reform Debate Journalists Reporting Journalism Binakuromo Ogbebor British Media Coverage of the Press Reform Debate Binakuromo Ogbebor British Media Coverage of the Press Reform Debate Journalists Reporting Journalism Binakuromo Ogbebor Journalism Studies The University of Sheffield Sheffield, UK ISBN 978-3-030-37264-4 ISBN 978-3-030-37265-1 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37265-1 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.