Trade Mark Opposition Decision (0/286/02)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'evoluzione Del Marchio Nel Comparto Alimentare Italiano

Dipartimento di Impresa e Management Laurea Triennale in Economia e Management Tesi di Laurea in Storia dell’economia e dell’impresa L’evoluzione del marchio nel comparto alimentare italiano RELATORE CANDIDATO Chiar.ma Prof.ssa Chiara Maiolino V. Ferrandino Matr. 176111 ANNO ACCADEMICO 2014-2015 INDICE Introduzione 2 CAPITOLO I – L’economia alimentare nell’economia italiana tra secondo dopoguerra e miracolo economico 3 1.1. Il dopoguerra e la ricostruzione industriale 3 1.2. L’industrializzazione italiana 6 1.3. L’industria e i grandi marchi italiani 16 CAPITOLO II – Il made in Italy alimentare nel contesto internazionale degli anni Settanta e Novanta 29 2.1. L’evoluzione del mercato italiano ed internazionale 29 2.2. Le concentrazioni industriali nel settore alimentare 39 2.3. Il made in Italy alimentare e l’evoluzione dei marchi italiani 49 CAPITOLO III – La sfida del nuovo millennio per il Made in Italy alimentare 68 3.1. L’Italia e la crisi economica: effetti sulla produzione industriale e analisi del comparto alimentare 68 3.2. Le ultime tendenze del made in Italy alimentare 75 3.3. Le nuove strategie di brand management dei marchi italiani 83 Conclusioni 89 Indice dei grafici 91 Indice delle tabelle 91 Indice delle figure 92 Riferimenti bibliografici 95 Sitografia 97 1 Introduzione Il seguente lavoro si propone di analizzare l’evoluzione dell’industria alimentare italiana in riferimento al contesto industriale italiano nonché all’evoluzione dei sistemi economici a livello internazionale e mondiale. Un’attenzione particolare è dedicata all’evoluzione dei consumi alimentari e al corrispondente progressivo adeguamento delle strategie di corporate branding messe in atto dalle principali imprese del settore. -

Product Catalog

Importers, Manufacturers & Distributors of Specialty Foods ATALO C MAY 2020 G www.krinos.com Importers, Manufacturers & Distributors of Specialty Foods 1750 Bathgate Ave. Bronx, NY 10457 Ph: (718) 729-9000 Atlanta | Chicago | New York ANTIPASTI . 17 APPETIZERS . 19 BEVERAGES . 34 BREADS . 26 CHEESE. 1 COFFEE & TEA. 32 CONFECTIONARY. 40 COOKING & BAKING . 37 DAIRY . 27 FISH . 28 HONEY. 11 JAMS & PRESERVES . 13 MEATS . 30 OILS & VINEGARS . 9 OLIVES . 5 PASTA, GRAINS, RICE & BEANS . 23 PEPPERS. 20 PHYLLO . 22 SEASONAL SPECIALTIES . 49 SNACKS . 39 SPREADS. 14 TAHINI. 16 VEGETABLES . 21 www.krinos.com CHEESE 20006 20005 20206 20102 20000 Athens Athens Krinos Krinos Krinos Feta Cheese - Domestic Feta Cheese - Domestic Feta Cheese - Domestic Feta Cheese - Domestic Feta Cheese - Domestic 8/4lb vac packs 5gal pail 2/8lb pails 10lb pail 5gal pail 21327 21325 21207 21306 21305 Krinos Krinos Krinos Krinos Krinos Dunavia Creamy Cheese Dunavia Creamy Cheese White Cheese - Bulgarian White Cheese - Bulgarian White Cheese - Bulgarian 12/400g tubs 8kg pail 12/14oz (400g) tubs 12/900g tubs 4/4lb tubs 21326 21313 21320 21334 21345 Krinos Krinos Krinos Krinos Krinos White Cheese - Bulgarian White Cheese - Bulgarian White Cheese - Bulgarian Greek Organic Feta Cheese Greek Organic Feta Cheese 2/4kg pails 6kg pail 5gal tin 12/5.3oz (150g) vac packs 12/14oz (400g) tubs 21202 21208 21206 21201 21205 Krinos Krinos Krinos Krinos Krinos Greek Feta Cheese Greek Feta Cheese Greek Feta Cheese Greek Feta Cheese Greek Feta Cheese 12/200g vac packs 2 x 6/250g wedges 12/14oz -

World's Top Billionaires 2016 23George Soros

World’s 100 BILLIONAIRES AS THE YEAR 2016 APPROACHES TO A GLORIOUS 2016 FINISH, URS-ASIaONE IS READY WITH ITS LIST OF WORLD’S TOP 100 BILLIONAIRES 2016. THE LIST IS ENTIRELY BASED ON THE NET WORTH OF EACH INDIVIDUAL. IT IS AN AWE-INSPIRING LIST, AS EVERY NAME LISTED HERE IS AN INSTITUTION IN HIMSELF/ HERSELF, WITH THEIR NET WORTH COMPARABLE TO ANNUAL BUDGETS OF SOME COUNTRIES. WE HAVE WEAVED SHORT INTERESTING STORIES AROUND THESE NAMES, WHICH WOULD ENTICE ALL READERS AND AFICIONADOS. 100 | ASIA ONE | JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2017 JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2017 | ASIA ONE | 101 100 World’s TOP BILLIONAIRES 2016 CARLOS SLIM HELU Net Worth: -$50 billion Chairman & CEO of Telmex 4 and América Móvil With a net worth equating about 6 percent of Mexico’s gross domestic product, Carlos Slim Helu is an epitome of astounding business acumen. Through extensive holdings in a considerable number of Mexican companies through his conglomerate Grupo Carso, he has his hands in most of the business portfolios one can think of- from education, health care, industrial manufacturing, transportation to real estate, media, energy, hospitality, entertainment, high-technology, retail, sports, and financial services. His real estate company Inmobiliaria Carso owns over 20 shopping centers, including ten in Mexico City, and operates stores in the country under U.S. brands BILL GATES including the Mexican arms of Saks Fifth Avenue, Sears and Net Worth: $75 billion the Coffee Factory. 1Technology Advisor, Microsoft Apart from leading a successful empire Slim has an avid affinity for baseball as well and he is a big supporter of the A business magnate, investor, author, philanthropist, and New York Yankees. -

Concorso a Premio “Puoi Vincere Ferrero Rocher Limited Edition- Ipersimply E Simply”

CONCORSO A PREMIO “PUOI VINCERE FERRERO ROCHER LIMITED EDITION- IPERSIMPLY E SIMPLY” Società Promotrice: FERRERO S.p.A. Sede Legale ed Amministrativa: P.le P.Ferrero, 1 - 12051 Alba (CN) Sede Direzionale: Via Maria Cristina, 47 - 10025 Pino Torinese (TO) Durata: dalle ore 9:00 del 16 novembre 2015 alle ore 24:00 del 27 dicembre 2015 Prodotti promozionati: specialità FERRERO: FERRERO ROCHER, POCKET COFFEE, MON CHERI, RAFFAELLO, FERRERO PRESTIGE, FERRERO COLLECTION, GRAND FERRERO ROCHER, FERRERO GOLDEN GALLERY (esclusi i formati stella, cubo e le confezioni in avancassa). Target partecipanti: utenti del sito internet www.piramidedibonta.it del territorio nazionale e con collegamento esclusivamente dall’Italia e dalla Repubblica di San Marino. Modalità di partecipazione: tutti coloro che acquistano almeno 2 confezioni a scelta tra le specialità FERRERO: FERRERO ROCHER, POCKET COFFEE, MON CHERI, RAFFAELLO, FERRERO PRESTIGE, FERRERO COLLECTION, GRAND FERRERO ROCHER, FERRERO GOLDEN GALLERY (esclusi i formati stella, cubo e confezioni in avancassa) presso i punti vendita della catena commerciale IPERSIMPLY e SIMPLY che aderiscono all’iniziativa e che espongono il materiale promozionale e conservano lo scontrino originale comprovante l’acquisto, si registrano sul sito www.piramidedibonta.it ed inseriscono i dati contenuti nello scontrino e caricano la foto dello scontrino nel formato .pdf o .jpeg (la dimensione massima del file dovrà essere di 10 MB) potranno vincere subito, tramite sistema random, 1 (una) delle 170 (centosettanta) confezioni di FERRERO ROCHER LIMITED EDITION. La spesa di connessione dipende dal contratto di collegamento sottoscritto dall’utente. La partecipazione al concorso comporta per l’utente l’accettazione incondizionata e totale delle regole e delle clausole contenute nel presente regolamento senza limitazione alcuna. -

Průvodce Košer Potravinami V České Republice Část II. Zahraniční

Průvodce košer potravinami v České republice Část II. Zahraniční produkty 5779 2018/2019 OBSAH 1. Vysvětlivky ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Zahraniční seznamy ................................................................................................................................ 6 Zkratky .................................................................................................................................................... 6 2. Kde nakoupit? ............................................................................................................................................ 7 3. Mléko a mléčné výrobky ............................................................................................................................ 9 Jogurty .................................................................................................................................................... 9 Jogurtové mléko, jogurtové nápoje ....................................................................................................... 9 Mléčný dezert ........................................................................................................................................ 9 Tvaroh a sýry .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Zmrzlina .............................................................................................. -

Q1 2018 Trend Report Consumer

An Acuris Company Global Sector Overview Consumer Trend Report Written by Amy Wu Senior Research Analyst Q1 2018 Mergermarket.com Mergermarket Sector Trend Report Consumer 2 Data analysis Global consumer sector M&A activity kicked off with the first quarter last year. Germany was on a lower note compared with last year, at 426 the most attractive target for global investors Regional Breakdown Trend transactions worth US$ 79.1bn in Q1, down 52.6% based on deal volume. The country attracted 33 2013—2018 Q1 by value year on year (508 deals, US$ 166.9bn). transactions in the first quarter of 2018, seven The dramatic decline can be largely attributed deals more than Q1 2017. to a lack of megadeals (>US$ 10bn) following a 500 15 Asia-Pacific (excl. Japan) dealmaking activity, on record-breaking 2017. 34 the other hand, saw growth in the sector with Consumer, which contributed 8.7% to the overall 73 deals worth US$ 13bn, up 15.3% compared 450 global M&A value, secured only one megadeal with Q1 2017. The top deal in the region was the 90.8 in the first quarter, three fewer than Q1 2017. US$ 2.1bn investment in China-based household 400 12 Still, 2018 marked the fourth highest Q1 since product retailer Easyhome by a group of investors 30.1 2009, highlighting Consumer’s positive stance for led by Alibaba and Chinese private equity 350 dealmaking. firms. With a dramatic 596.4% increase in value 29.8 60.1 compared with Q1 2017, Chinese investors were The US continued to account for the bulk of 300 9 Market (%) share actively seeking European targets in this sector. -

La Diversificazione Correlata E Il Caso Nutella Biscuits

Cattedra RELATORE CANDIDATO Anno Accademico INDICE INTRODUZIONE I CAPITOLO LA DIVERSIFICAZIONE 1.1 Il concetto di diversificazione. 1.2 Diversificazione di prodotto e diversificazione geografica, cenni. 1.3 La diversificazione geografica II CAPITOLO I DIVERSI PLAYER DEL SETTORE 2.1 Settore di riferimento 2.2 Competitors 2.3 Ferrero e il modello delle cinque forze di Porter III CAPITOLO CASE HISTORY NUTELLA BISCUITS STORIA DELLA FERRERO 3.1 Le diverse strategie della Ferrero 3.2 Analisi case history Nutella Biscuits 3.3Conclusioni Bibliografia Sitografia INTRODUZIONE Modello di un marchio “made in Italy”, produttore di prodotti dolciari e cioccolato, Ferrero è uno dei migliori esempi per definire il settore privato del dopoguerra in questo paese. Dalla creazione del prodotto di punta, Nutella, il gruppo ha lanciato con successo oltre 30 prodotti. Il Gruppo Ferrero è ora il quarto produttore di cioccolato e pasticceria, dietro Nestlé, Mars e Mondelez International. La capacità di innovare e investire su nuovi mercati ha portato Ferrero a suscitare nuove abitudini di consumo, puntando a un obiettivo in crescita, in particolare con il dipartimento Ricerca e Sviluppo, una delle forze principali dell'azienda, portando quotidianamente nuovi concetti dolciari. L'azienda di famiglia ha sempre rifiutato qualsiasi partnership o azionista esterno all'azienda, mantenendo la privacy nella gestione ed evidenziando lo sviluppo interno. Un'altra chiave del successo è il rapporto tra l'azienda e i suoi dipendenti, intriso dei valori e della cultura di Ferrero. Nonostante il suo status indipendente, Ferrero vuole estendere le sue attività, in particolare verso l'Asia e il mercato americano, poiché l'80% delle vendite è realizzato in Europa. -

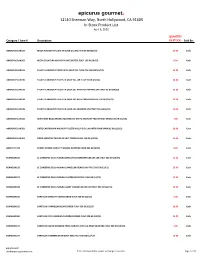

Epicurus Gourmet. 12140 Sherman Way, North Hollywood, CA 91605 in STOCK PRODUCT LIST April 30, 2020

epicurus gourmet. 12140 Sherman Way, North Hollywood, CA 91605 IN STOCK PRODUCT LIST April 30, 2020 QUANTITY Category / Item # Description: Sold By: IN STOCK: ANCHOVIES:AN163 RECCA COLATURA ANCHOVY JUICE BOTTLE ITALY 100 ML (6/CS) Each 5.00 ANCHOVIES:AN185 TALATTA ANCHOVY PASTE WITH OLIVE OIL TUBE ITALY 60 GR (24/CS) Each 25.00 ANCHOVIES:AN190 TALATTA ANCHOVY FILLETS IN OLIVE OIL JAR ITALY 95 GR (24/CS) Each 12.00 ANCHOVIES:AN191 TALATTA ANCHOVY FILLETS IN OLIVE OIL WITH HOT PEPPERS JAR ITALY 95 GR (24/CS) Each 20.00 ANCHOVIES:AN192 TALATTA ANCHOVY FILLETS IN OLIVE OIL WITH CAPERS JAR ITALY 95 GR (24/CS) Each 7.00 ANCHOVIES:AN325 BENFUMAT BOQUERONES MARINATED WHITE ANCHOVY FILLETS TRAY SPAIN 130 GR (10/CS) Each 2.00 ANCHOVIES:AN350 ORTIZ CANTABRIAN ANCHOVY FILLETS IN OLIVE OIL JAR WITH FORK SPAIN 95 GR (15/CS) Each 18.00 ANCHOVIES:AN365 ORTIZ ANCHOVY PACKED IN SALT POUCH SPAIN 120 GR (12/CS) Each 26.00 BARLEY:TL175 PURPLE PRAIRIE BARLEY TIMELESS NATURAL FOOD 454 GR (8/CS) Each 10.00 BEANS:BN125 LE CONSERVE DELLA NONNA BORLOTTI (CRANBERRY) BEANS JAR ITALY 360 GR (12/CS) Each 8.00 BEANS:BN126 LE CONSERVE DELLA NONNA CANNELLINI BEANS JAR ITALY 360 GR (12/CS) Each 10.00 BEANS:BN127 LE CONSERVE DELLA NONNA CHICKPEAS JAR ITALY 360 GR (12/CS) Each 8.00 BEANS:BN150 BARTOLINI BORLOTTI BEANS DRIED ITALY 500 GR (12/CS) Each 5.00 BEANS:BN160 BARTOLINI CECI UMBRIAN CHICKPEAS DRIED ITALY 500 GR (12/CS) Each 13.00 BEANS:BN175 BARTOLINI FARMERS BEAN SOUP MIX ITALY 500 GR (12/CS) Each 6.00 BEANS:BN220 SABAROT DRIED MOGETTES OF VENDEE BEANS LABEL ROUGE FRANCE 500 GR (10/CS) Each 14.00 BEANS:BN428 LLANO SECO HEIRLOOM PINQUITO BEANS BAG CALIFORNIA 16 OZ (8/CS) Each 1.00 BEANS:BN436 LLANO SECO BLACK CALYPSO HEIRLOOM BEANS REPACK 1 LB Each 23.00 BEANS:BN446 LLANO SECO CANARIO HEIRLOOM BEANS REPACK 1 LB Each 24.00 BEANS:BN451 LLANO SECO CANNELLINI BEANS 1 LB Each 22.00 818-658-3637 [email protected] Prices and availability subject to change at anytime. -

In Stock Product List April 8, 2020

epicurus gourmet. 12140 Sherman Way, North Hollywood, CA 91605 In Stock Product List April 8, 2020 QUANTITY Category / Item # Description: IN STOCK: Sold By: ANCHOVIES:AN155 RECCA ANCHOVY FILLETS IN OLIVE OIL ITALY TIN 56 GR (25/CS) 20.00 Each ANCHOVIES:AN163 RECCA COLATURA ANCHOVY JUICE BOTTLE ITALY 100 ML (6/CS) 6.00 Each ANCHOVIES:AN185 TALATTA ANCHOVY PASTE WITH OLIVE OIL TUBE ITALY 60 GR (24/CS) 38.00 Each ANCHOVIES:AN190 TALATTA ANCHOVY FILLETS IN OLIVE OIL JAR ITALY 95 GR (24/CS) 28.00 Each ANCHOVIES:AN191 TALATTA ANCHOVY FILLETS IN OLIVE OIL WITH HOT PEPPERS JAR ITALY 95 GR (24/CS) 23.00 Each ANCHOVIES:AN192 TALATTA ANCHOVY FILLETS IN OLIVE OIL WITH CAPERS JAR ITALY 95 GR (24/CS) 12.00 Each ANCHOVIES:AN195 TALATTA ANCHOVY FILLETS IN OLIVE OIL HERMETIC JAR ITALY 235 GR (6/CS) 10.00 Each ANCHOVIES:AN325 BENFUMAT BOQUERONES MARINATED WHITE ANCHOVY FILLETS TRAY SPAIN 130 GR (10/CS) 7.00 Each ANCHOVIES:AN350 ORTIZ CANTABRIAN ANCHOVY FILLETS IN OLIVE OIL JAR WITH FORK SPAIN 95 GR (15/CS) 29.00 Each ANCHOVIES:AN365 ORTIZ ANCHOVY PACKED IN SALT POUCH SPAIN 120 GR (12/CS) 16.00 Each BARLEY:TL175 PURPLE PRAIRIE BARLEY TIMELESS NATURAL FOOD 454 GR (8/CS) 8.00 Each BEANS:BN125 LE CONSERVE DELLA NONNA BORLOTTI (CRANBERRY) BEANS JAR ITALY 360 GR (12/CS) 11.00 Each BEANS:BN126 LE CONSERVE DELLA NONNA CANNELLINI BEANS JAR ITALY 360 GR (12/CS) 25.00 Each BEANS:BN127 LE CONSERVE DELLA NONNA CHICKPEAS JAR ITALY 360 GR (12/CS) 17.00 Each BEANS:BN128 LE CONSERVE DELLA NONNA GIANT CORONA BEANS JAR ITALY 360 GR (12/CS) 13.00 Each BEANS:BN150 BARTOLINI BORLOTTI BEANS DRIED ITALY 500 GR (12/CS) 1.00 Each BEANS:BN155 BARTOLINI CANNELLINI BEANS DRIED ITALY 500 GR (12/CS) 18.00 Each BEANS:BN160 BARTOLINI CECI UMBRIAN CHICKPEAS DRIED ITALY 500 GR (12/CS) 24.00 Each BEANS:BN170 BARTOLINI QUICK COOKING PEARL BARLEY, LENTIL & BEAN SOUP MIX ITALY 500 GR (12/CS) 4.00 Each BEANS:BN175 BARTOLINI FARMERS BEAN SOUP MIX ITALY 500 GR (12/CS) 14.00 Each 818-658-3637 [email protected] Prices and availability subject to change at anytime. -

Managing Marketing Information

PART 1: Defining Marketing and the Marketing Process (Chapters 1–2) PART 2: Understanding the Marketplace and Consumer Value (Chapters 3–6) PART 3: Designing a Customer Value–Driven Strategy and Mix (Chapters 7–17) PART 4: Extending Marketing (Chapters 18–20) Managing Marketing Information 4 to Gain Customer Insights In this chapter, we continue our exploration of how Let’s start with a story about marketing research and cus- marketers gain insights into consumers and the mar- tomer insights in action. In order to tailor its products to the ketplace. We look at how companies develop and market it operates in, Italian chocolate and confectionary manu- manage information about important marketplace ele- facturer Ferrero derives fresh insights on customers and the REVIEW CHAPTER P ments: customers, competitors, products, and mar- marketplace from marketing information. The company’s ability keting programs. To succeed in today’s marketplace, companies to use this information and capitalize on them by improving deci- must know how to turn mountains of marketing information into sion making and tailoring their offerings to the local market has fresh customer insights that will help them engage customers and been a key success factor in major and growing markets such deliver greater value to them. as India. FERRERO: Managing Marketing Information and Customer Insights errero SpA is an Italian manufacturer of branded choc- chocolate in India with the help of sophisticated marketing olate and confectionery products, and the third big- analysis. gest chocolate producer and confectionery company When Ferrero entered India in 2004, the country did not in the world. -

Children, Media and Consumption on the Front Edge

O CH Yearbook 2007 N I L T dren H E front ,M edia edge and CHILdren, C edia and onsum M ConsumPtion P tion The International Clearinghouse ON THE on Children, Youth and Media with the support from UNESCO in producing the yearbook front NORDICOM Nordic Information Centre for Media and Communication Research Göteborg University edge Box 713, SE 405 30 Göteborg, Sweden Telephone: +46 31 786 00 00 Fax: +46 31 786 46 55 & TUFTE BIRGITTE KARIN M. EKSTRÖM EDITORS: www.nordicom.gu.se EDITORS: ISBN 978-91-89471-51-1 KARIN M. EKSTRÖM & BIRGITTE TUFTE The International Clearinghouse ISBN 978-91-89471-51-1 on Children, Youth and Media NORDICOM 9 789189 471511 Göteborg University Yearbook 2007 The International The International Clearinghouse Clearinghouse on Children, Youth and Media, at on Children, Youth and Media A UNESCO INITIATIVE 1997 Nordicom Göteborg University Box 713 SE 405 30 GÖTEBORG, Sweden In 1997, the Nordic Information Centre for Media and Web site: Communication Research (Nordicom), Göteborg www.nordicom.gu.se/clearinghouse University Sweden, began establishment of the International Clearinghouse on Children, Youth and DIRECTOR: Ulla Carlsson Media, financed by the Swedish government and SCIENTIFIC CO-ORDINATOR: UNESCO. The overall point of departure for the Cecilia von Feilitzen Tel:+46 8 608 48 58 Clearinghouse’s efforts with respect to children, youth Fax:+46 8 608 46 40 and media is the UN Convention on the Rights of the E-mail: [email protected] Child. INFORMATION CO-ORDINATOR: The aim of the Clearinghouse is to increase Catharina Bucht awareness and knowledge about children, youth and Tel: +46 31 786 49 53 media, thereby providing a basis for relevant policy- Fax: +46 31 786 46 55 making, contributing to a constructive public debate, E-mail: [email protected] and enhancing children’s and young people’s media literacy and media competence. -

Concorso a Premio “Puoi Vincere I Flute Per Il Tuo Bar ”

CONCORSO A PREMIO “PUOI VINCERE I FLUTE PER IL TUO BAR ” Società Promotrice: FERRERO S.p.A. Sede Legale ed Amministrativa: P.le P.Ferrero, 1 - 12051 Alba (CN) Sede Direzionale: Via Maria Cristina, 47 - 10025 Pino Torinese (TO) Durata: dal 9 novembre 2015 al 27 dicembre 2015 Modalità di partecipazione: tutti coloro che, nel periodo dal 9 novembre 2015 al 27 dicembre 2015, si recano nei Cash & Carry che aderiscono all’iniziativa ed espongono il materiale promozionale e, acquistano almeno 2 cartoni di PRALINE a scelta tra quelli sottoelencati*, telefonando da un apparecchio a toni non schermato al n. 06/91810429** (seguendo le indicazioni della voce registrata, digitando i seguenti dati riportati sulla fattura: data (ggmm), numero ed importo totale), potranno scoprire subito se hanno vinto 1 confezione contenente 20 flute. Il sistema di gestione del concorso provvederà a ripartire i premi in palio, nel periodo di promozione, in maniera del tutto casuale, tramite un server e un software non manomettibile. Il server ha sede c/o ICTlabs S.r.l. ospitati nel TLC & Data Center Eurnetcity di EurFacility S.p.A. in Via della Civiltà del Lavoro, 52 - 00144 Roma (Italy) con sede legale a Largo Adenauer, 1A - 00144 Roma (Italy) Ogni fattura consente una sola partecipazione al concorso. Coloro che hanno vinto il premio, per averne diritto, devono spedire entro sette giorni dalla vincita, è consigliabile tramite raccomandata A.R. (farà fede il timbro postale) la fotocopia della fattura comprovante la vincita (che riporti data, numero ed importo totale indicati) insieme ai loro dati anagrafici (cognome e nome) ed ai loro recapiti (indirizzo della sede legale e recapito telefonico della sede legale) a: Concorso “Puoi vincere i flute per il tuo bar” c/o ICTLABS SRL– VIA NARNI 211 int.14 – 05100 TERNI.