National Park Service This Form Is for Use in Documenting Multiple

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yanawant: Paiute Places and Landscapes in the Arizona Strip

Yanawant Paiute Places and Landscapes in the Arizona Strip Volume Two OfOfOf The Arizona Strip Landscapes and Place Name Study Prepared by Diane Austin Erin Dean Justin Gaines December 12, 2005 Yanawant Paiute Places and Landscapes in the Arizona Strip Volume Two Of The Arizona Strip Landscapes and Place Name Study Prepared for Bureau of Land Management, Arizona Strip Field Office St. George, Utah Prepared by: Diane Austin Erin Dean Justin Gaines Report of work carried out under contract number #AAA000011TOAAF030023 2 Table of Contents Preface……………………………………………………………………………………………ii i Chapter One: Southern Paiute History on the Arizona Strip………………………………...1 Introduction.............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Early Southern Paiute Contact with Europeans and Euroamericans ........................... 5 1.2 Southern Paiutes and Mormons ........................................................................................ 8 1.3 The Second Powell Expedition......................................................................................... 13 1.4 An Onslaught of Cattle and Further Mormon Expansion............................................ 16 1.5 Interactions in the First Half of the 20 th Century ......................................................... 26 Chapter Two: Southern Paiute Place Names On and Near the Arizona Strip 37 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... -

Grand Canyon

ALT ALT To 389 To 389 To Jacob Lake, 89 To 89 K and South Rim a n a b Unpaved roads are impassable when wet. C Road closed r KAIBAB NATIONAL FOREST e in winter e K k L EA O N R O O B K NY O A E U C C N T E N C 67 I A H M N UT E Y SO N K O O A N House Rock Y N N A Buffalo Ranch B A KANAB PLATEAU C C E A L To St. George, Utah N B Y Kaibab Lodge R Mount Trumbull O A N KAIBAB M 8028ft De Motte C 2447m (USFS) O er GR C o Riv AN T PLATEAU K HUNDRED AND FIFTY MIL lorad ITE ap S NAVAJO E Co N eat C A s C Y RR C N O OW ree S k M INDIAN GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK B T Steamboat U Great Thumb Point Mountain C RESERVATION K 6749ft 7422ft U GREAT THUMB 2057m 2262m P Chikapanagi Point MESA C North Rim A 5889ft E N G Entrance Station 1795m M Y 1880ft FOSSIL R 8824ft O Mount Sinyala O U 573m G A k TUCKUP N 5434ft BAY Stanton Point e 2690m V re POINT 1656m 6311ft E U C SB T A C k 1924m I E e C N AT A e The Dome POINT A PL N r o L Y Holy Grail l 5486ft R EL Point Imperial C o Tuweep G W O Temple r 1672m PO N Nankoweap a p d H E o wea Mesa A L nko o V a Mooney D m N 6242ft A ID Mount Emma S Falls u 1903m U M n 7698ft i Havasu Falls h 2346m k TOROWEAP er C Navajo Falls GORGE S e v A Vista e i ITE r Kwagunt R VALLEY R N N Supai Falls A Encantada C iv o Y R nt Butte W d u e a O G g lor Supai 2159ft Unpaved roads are North Rim wa 6377ft r o N K h C Reservations required. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for the USA (W7A

Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7A - Arizona) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S53.1 Issue number 5.0 Date of issue 31-October 2020 Participation start date 01-Aug 2010 Authorized Date: 31-October 2020 Association Manager Pete Scola, WA7JTM Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Document S53.1 Page 1 of 15 Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE CONTROL....................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Program Derivation ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 General Information ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Final Ascent -

Spagnuolo.Pdf

University of Utah UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL ESTABLISHING A TEMPORAL DISTRIBUTION FOR CERAMICS OF THE WASHINGTON COUNTY, UT VIRGIN RIVER BRANCH OF THE ANCESTRAL PUEBLOAN Crystal Spagnuolo (Dr. Brian Codding; Kenneth Blake Vernon, MA) Department of Anthropology Dating archaeological sites is important for establishing patterns in settlement, trade, resource use, and population estimates of prehistoric peoples. Using dated sites, we can see patterns in how a culture such as the Ancestral Puebloan went from a foraging subsistence to agricultural settlements with far-reaching trade networks. Or, we can understand when the Ancestral Puebloan abandoned certain areas of the American Southwest and pair this with climate data to understand how climate might be a factor. In order to do so however, we must first have a reliable timeline of these events, built from archaeological sites that are reliably dated. Unfortunately, direct dating via radiocarbon or dendrochronology is costly and not always possible due to the biodegradable nature of the organic materials needed for such dating. Using a relative dating system that employs ceramics is a cost-effective alternative. Here I continue work begun by The Archaeological Center at the University of Utah to generate a ceramic dating system for the area encompassing Southwest Utah, focusing on Washington County, using extant site data from this region. While the prehistoric inhabitants of this area were Ancestral Puebloan, the ceramic traditions were separate, and therefore merit their own dating analysis (Lyneis, 1995; Spangler, Yaworsky, Vernon, & Codding, 2019). Currently, dating of sites in the region is difficult, both due to the expense of direct dating techniques (radiocarbon and dendrochronology) and the lack of defined time periods for ceramics types. -

Geographic Names

GEOGRAPHIC NAMES CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES ? REVISED TO JANUARY, 1911 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1911 PREPARED FOR USE IN THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE BY THE UNITED STATES GEOGRAPHIC BOARD WASHINGTON, D. C, JANUARY, 1911 ) CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES. The following list of geographic names includes all decisions on spelling rendered by the United States Geographic Board to and including December 7, 1910. Adopted forms are shown by bold-face type, rejected forms by italic, and revisions of previous decisions by an asterisk (*). Aalplaus ; see Alplaus. Acoma; township, McLeod County, Minn. Abagadasset; point, Kennebec River, Saga- (Not Aconia.) dahoc County, Me. (Not Abagadusset. AQores ; see Azores. Abatan; river, southwest part of Bohol, Acquasco; see Aquaseo. discharging into Maribojoc Bay. (Not Acquia; see Aquia. Abalan nor Abalon.) Acworth; railroad station and town, Cobb Aberjona; river, IVIiddlesex County, Mass. County, Ga. (Not Ackworth.) (Not Abbajona.) Adam; island, Chesapeake Bay, Dorchester Abino; point, in Canada, near east end of County, Md. (Not Adam's nor Adams.) Lake Erie. (Not Abineau nor Albino.) Adams; creek, Chatham County, Ga. (Not Aboite; railroad station, Allen County, Adams's.) Ind. (Not Aboit.) Adams; township. Warren County, Ind. AJjoo-shehr ; see Bushire. (Not J. Q. Adams.) Abookeer; AhouJcir; see Abukir. Adam's Creek; see Cunningham. Ahou Hamad; see Abu Hamed. Adams Fall; ledge in New Haven Harbor, Fall.) Abram ; creek in Grant and Mineral Coun- Conn. (Not Adam's ties, W. Va. (Not Abraham.) Adel; see Somali. Abram; see Shimmo. Adelina; town, Calvert County, Md. (Not Abruad ; see Riad. Adalina.) Absaroka; range of mountains in and near Aderhold; ferry over Chattahoochee River, Yellowstone National Park. -

Karen G. Harry

Karen G. Harry Department of Anthropology University of Nevada Las Vegas 4505 Maryland Parkway, Box 45003 Las Vegas, NV 89154-5003 (702) 895-2534; [email protected] Professional Employment 2014-present Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Nevada Las Vegas 2007-2014 Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Nevada Las Vegas 2001-2007 Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Nevada Las Vegas 1997-2001 Director of Cultural Resources, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Austin 1997 Adjunct Faculty, Pima Community College, Tucson 1990-1996 Project Director, Statistical Research, Inc., Tucson Education 1997 Ph.D., University of Arizona, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona 1987 M.A., Anthropology, University of Arizona 1982 B.A., Anthropology, Texas A&M University, cum laude Research Interests Southwestern archaeology; ceramic analysis, sourcing, and technology; organization of craft production; trade and exchange issues; chemical compositional analysis; prehistoric leadership strategies; prehistoric community organization Ongoing Field Projects Field Research on the Parashant National Monument: I am involved in a long-term archaeological research project concerning the Puebloan occupation of the Mt. Dellenbaugh area of the Shivwits Plateau, located within Parashant National Monument. Field and Archival Research in the Lower Moapa Valley: A second area of ongoing research involves the Puebloan occupation of the lower Moapa Valley of southern Nevada. I have recently completed an archival study of the artifacts and records associated with the early (1920s-1940s) field research of this area, and have on-going field investigations in the area. updated Sept. 1 , 2020 Books & Special Issues of Journals 2019 Harry, Karen G. and Sachiko Sakai (guest editors). -

Grand Canyon National Park

To Bryce Canyon National Park, KANAB To St. George, Utah To Hurricane, Cedar City, Cedar Breaks National Monument, To Page, Arizona To Kanab, Utah and St. George, Utah V and Zion National Park Gulch E 89 in r ucksk ive R B 3700 ft R M Lake Powell UTAH 1128 m HILDALE UTAH I L ARIZONA S F COLORADO I ARIZONA F O gin I CITY GLEN CANYON ir L N V C NATIONAL 89 E 4750 ft N C 1448 m RECREATION AREA A L Glen Canyon C FREDONIA I I KAIBAB INDIAN P Dam R F a R F ri U S a PAGE RESERVATION H 15 R i ve ALT r 89 S 98 N PIPE SPRING 3116 ft I NATIONAL Grand Canyon National Park 950 m 389 boundary extends to the A MONUMENT mouth of the Paria River Lees Ferry T N PARIA PLATEAU To Las Vegas, Nevada U O Navajo Bridge M MARBLE CANYON r e N v I UINKARET i S G R F R I PLATEAU F I 89 V E R o V M L I L d I C a O r S o N l F o 7921ft C F 2415 m K I ANTELOPE R L CH JACOB LAKE GUL A C VALLEY ALT P N 89 Camping is summer only E L O K A Y N A S N N A O C I O 89T T H A C HOUSE ROCK N E L E N B N VALLEY YO O R AN C A KAIBAB NATIONAL Y P M U N P M U A 89 J L O C FOREST O K K D O a S U N Grand Canyon National Park- n F T Navajo Nation Reservation boundary F a A I b C 67 follows the east rim of the canyon L A R N C C Y r O G e N e N E YO k AN N C A Road to North Rim and all TH C OU Poverty Knoll I services closed in winter. -

Grand Canyon

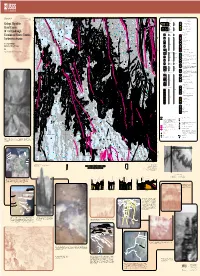

U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Investigations Series I–2688 14 Version 1.0 4 U.S. Geological Survey 167.5 1 BIG SPRINGS CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS LIST OF MAP UNITS 4 Pt Ph Pamphlet accompanies map .5 Ph SURFICIAL DEPOSITS Pk SURFICIAL DEPOSITS SUPAI MONOCLINE Pk Qr Holocene Qr Colorado River gravel deposits (Holocene) Qsb FAULT CRAZY JUG Pt Qtg Qa Qt Ql Pk Pt Ph MONOCLINE MONOCLINE 18 QUATERNARY Geologic Map of the Pleistocene Qtg Terrace gravel deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pc Pk Pe 103.5 14 Qa Alluvial deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Pt Pc VOLCANIC ROCKS 45.5 SINYALA Qti Qi TAPEATS FAULT 7 Qhp Qsp Qt Travertine deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Grand Canyon ၧ DE MOTTE FAULT Pc Qtp M u Pt Pleistocene QUATERNARY Pc Qp Pe Qtb Qhb Qsb Ql Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) Qsb 1 Qhp Ph 7 BIG SPRINGS FAULT ′ × ′ 2 VOLCANIC DEPOSITS Dtb Pk PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTARY ROCKS 30 60 Quadrangle, Mr Pc 61 Quaternary basalts (Pleistocene) Unconformity Qsp 49 Pk 6 MUAV FAULT Qhb Pt Lower Tuckup Canyon Basalt (Pleistocene) ၣm TRIASSIC 12 Triassic Qsb Ph Pk Mr Qti Intrusive dikes Coconino and Mohave Counties, Pe 4.5 7 Unconformity 2 3 Pc Qtp Pyroclastic deposits Mr 0.5 1.5 Mၧu EAST KAIBAB MONOCLINE Pk 24.5 Ph 1 222 Qtb Basalt flow Northwestern Arizona FISHTAIL FAULT 1.5 Pt Unconformity Dtb Pc Basalt of Hancock Knolls (Pleistocene) Pe Pe Mၧu Mr Pc Pk Pk Pk NOBLE Pt Qhp Qhb 1 Mၧu Pyroclastic deposits Qhp 5 Pe Pt FAULT Pc Ms 12 Pc 12 10.5 Lower Qhb Basalt flows 1 9 1 0.5 PERMIAN By George H. -

Final Wilderness Recommendation

Final Wilderness Recommendation 2010 Update Grand Canyon National Park Arizona National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior NOTE: This document is a draft update to the park’s 1980 Final Wilderness Recommendation submitted to the Department of Interior in September 1980. The 1980 recommendation has never been forwarded to the president and Congress for legislative action. The 2010 draft update is to reconcile facts on the ground and incorporate modern mapping tools (Geographical Information Systems), but it does not alter the substance of the original recommendation. In 1993, the park also completed an update that served as a resource for the 2010 draft update. The official wilderness recommendation map remains the map #113-40, 047B, submitted to the Department of Interior in 1980. FINAL WILDERNESS RECOMMENDATION 2010 Update GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK ARIZONA THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE RECOMMENDS THAT WILDERNESS OF 1,143,918 ACRES WITHIN GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK, ARIZONA, AS DESCRIBED IN THIS DOCUMENT, BE DESIGNATED BY AN ACT OF CONGRESS. OF THIS TOTAL, 1,117,457 ACRES ARE RECOMMENDED FOR IMMEDIATE DESIGNATION, AND 26,461 ACRES ARE RECOMMENDED FOR DESIGNATION AS POTENTIAL WILDERNESS PENDING RESOLUTION OF BOUNDARY AND MOTORIZED RIVER ISSUES. 2 Table of Contents I. Requirement for Study 4 II. Wilderness Recommendation 4 III. Wilderness Summary 4 IV. Description of the Wilderness Units 5 Unit 1: Grand Wash Cliffs 5 Unit 2: Western Park 5 (a) Havasupai Traditional Use Lands 6 (b) Sanup Plateau 7 (c) Uinkaret Mountains 7 (d) Toroweap Valley 8 (e) Kanab Plateau 8 - Tuckup Point 8 - SB Point 8 (f) North Rim 8 (g) Esplanade 9 (h) Tonto Platform 9 (i) Inner Canyon 9 (j) South Rim (west of Hermits Rest) 9 (k) Recommended Potential wilderness 9 - Colorado River 9 - Curtis-Lee Tracts 9 (l) Non-wilderness 9 - Great Thumb 9 - North Rim Primitive Roads 10 - Kanab Plateau Primitive Roads 10 Unit 3: Eastern Park 10 (a) Potential Wilderness 11 - Private Lands 11 - Colorado River 12 (b) Non-wilderness: North Rim Paved Roads 12 Unit 4: The Navajo Indian Properties 12 VI. -

Southwest Places to Visit Or

Places to Visit or Collect in the Southwestern United States Places to Visit or Collect in the Southwestern United States By Thomas Farley Revision 002, September 26th, 2019. (Version 001 was incorrectly labeled October 1, 2019) https://www.patreon.com/writingrockhound (more good stuff!) [email protected] (comments, corrections, and additions wanted!) These are places I visited or were recommended to me while traveling in the Southwest for my book. I mostly visited rock related places and ground open to collecting. Weather wise, October may be the best time to travel the Southwest, followed by May. It is impractical to visit every place you want to go because day after day you will find certain stores, mines, and museums closed. Traveling Monday through Thursday is especially tough, my advice is to prospect or collect on those days and then try to visit businesses and museums closer to the weekend. You will have to return to the Southwest to visit places closed on your first travel. I envy you. German motorcyclist balancing on the Four Corners Monument 1 By Thomas Farley: https://www.patreon.com/writingrockhound Arizona (and one exception in Utah) James Mitchell’s Gem Trails of Arizona is dated but essential. Anyone traveling extensively off-pavement in Arizona should get an Arizona State Trust Land Permit. $15.00 for an individual. Rockhounding on Arizona State Trust Land is prohibited but stopping at any point on these lands constitutes a “use” and that use demands a permit. Determining where these properties exists while driving is impractical, most are managed grazing land outside of small towns or settlements. -

Parashant Partnership

Parashant Partnership Arizona 1 million acres The Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument in northern Arizona is a remote and undeveloped land- scape and includes some of the most scenic and wildest places in America. The monument was set aside in 2000 by presidential proclamation to protect the unique and rich biological, geological, paleontological and cultural resources in the area. The primary purpose for the man- Both Native Americans and more recent European Americans have lived agement of this monument is to ensure that the objects and raised families and built communities in this vast, wild and scenic landscape. In spite of its apparent austerity, the Parashant sustains those of interest identified in the proclamation that set aside who have settled here. the monument are protected. Above: landscape, petroglyphs, schoolhouse at Mt. Trumbull © Scott Jones Restoring fire regimes is key to the restoration of the The landscape, with elevations ranging from the banks of the Colorado River to the peaks of Mount Logan and Mount Trumbull, also supports Parashant National Monument landscape. The absence a rich diversity of wildlife, including (below) the federally-listed Mojave of fire in ponderosa forests has resulted in tree densities desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) and California condor (Gymnogyps almost 20 times those of a century and a half ago; these californianus). tortoise © NPS; condor © Michael Quinn/NPS forests have moved from high-frequency, low-intensity fires toward a condition in which the potential for un- naturally high intensity fire is substantial—and likely to increase as the climate changes. In the Great Basin re- gion, young pinyon-juniper stands are encroaching into the sagebrush and grasslands because lingering effects of past management practices have tipped the competi- tive balance between the species towards the trees. -

Aboriginal Hunter-Gatherer Adaptations of Zion National Park, Utah

• D-"15 ABORIGINAL HUNTER-GATHERER ADAPTATIONS OFL..ZION NATIONAL PARK, UTAH • National Park Service Midwest Archeological Center • PLEASE RETURN TO: TECHNICAL INFORMATION CENTER ON t.11CROFILM DENVER SERVICE CENTER S(~ANN~O NATIONAL PARK SERVICE J;/;-(;_;o L • ABORIGINAL HUNTER-GATHERER ADAPTATIONS OF ZION NATIONAL PARK, UTAH by Gaylen R. Burgett • Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report No. 1 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Midwest Archeological Center Lincoln, Nebraska • 1990 ABSTRACT This report presents the results of test excavations at sites 42WS2215, 42WS2216, and 42WS2217 in Zion National Park in • southwestern Utah. The excavations were conducted prior to initiating a land exchange and were designed to assess the scientific significance of these sites. However, such an assessment is dependent on the archaeologists' ability to link the static archaeological record to current anthropological and archaeological questions regarding human behavior in the past. Description and analysis of artifacts and ecofacts were designed to identify differences and similarities between these particular sites. Such archaeological variations were then linked to the structural and organizational features of hunter gatherer adaptations expected for the region including Zion National Park. These expected adaptations regarding the nature of hunter-gatherer lifeways are derived from current evolutionary ecological, cross-cultural, and ethnoarchaeological ideas. Artifact assemblages collected at sites 42WS2217 and 42WS2216 are related to large mammal procurement and plant processing. Biface thinning flakes and debitage characteristics suggest that stone tools were manufactured and maintained at these locations. Site furniture such as complete ground stone manos and metates, as well as ceramic vessel fragments, may also indicate that these sites were repetitively used by logistically organized hunter-gatherers or collectors.