A Systematic Review for Geographic and Topic Scopes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rural Young Children with Disabilities: Education, Challenges, and Opportunities

International Journal on Studies in Education Volume 2, Issue 2, 2020 ISSN: 2690-7909 Rural Young Children with Disabilities: Education, Challenges, and Opportunities Novuyo Nkomo, Department of Early Childhood Care & Development, Southern Africa Nazarene University, Eswatini Adiele Dube Department of Health Education, Southern Africa Nazarene University, Eswatini, [email protected] Donna Marucchi Department of Early Childhood Care & Development, Southern Africa Nazarene University, Eswatini Abstract: The plight of young children with disabilities who live in rural communities remains unsolved issue in many developing countries. Culturally, many people have negative beliefs regarding the causes of disabilities. Disability may be associated with punishment by gods, ancestral spirits resulting from mother‟s promiscuity during pregnancy, witchcraft, or evil spirits. This article focuses on challenges and opportunities of young children with disabilities who live in the rural communities of Eswatini and Zimbabwe, and related to accessing early childhood development (ECD) education services. Lessons drawn between the two countries reveal that in Eswatini, the Disability Unit which caters for disability issues is under the Social Welfare Department and is accommodated in the Deputy Prime Minister‟s Office. In Zimbabwe, Chikwature, Oyedele and Ntini (2016) noted that an inclusive education policy is still yet to be drafted. Disability issues are still not fully represented constitutionally. Using the social exclusion theory enabled the researcher to determine how deeply rooted social exclusion is in the attitudes of teachers and rural communities. Using interviews and focus group discussions, 30 parents/caregivers for children with disabilities, aged 4 to 5 years, were purposively sampled for study. Results showed that the failure of these children to access ECD services in the community impacts negatively on their holistic development. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Abkhaz in Ukraine Abor in India Population: 1,500 Population: 1,700 World Popl: 307,600 World Popl: 1,700 Total Countries: 6 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: Caucasus People Cluster: South Asia Tribal - other Main Language: Abkhaz Main Language: Adi Main Religion: Non-Religious Main Religion: Unknown Status: Minimally Reached Status: Minimally Reached Evangelicals: 1.00% Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 20.00% Chr Adherents: 16.36% Scripture: New Testament Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Apsuwara - Wikimedia "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Achuar Jivaro in Ecuador Achuar Jivaro in Peru Population: 7,200 Population: 400 World Popl: 7,600 World Popl: 7,600 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South American Indigenous People Cluster: South American Indigenous Main Language: Achuar-Shiwiar Main Language: Achuar-Shiwiar Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Status: Minimally Reached Status: Minimally Reached Evangelicals: 1.00% Evangelicals: 2.00% Chr Adherents: 14.00% Chr Adherents: 15.00% Scripture: New Testament Scripture: New Testament www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Gina De Leon Source: Gina De Leon "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Adi in India Adi Gallong in India -

Uneswa Journal of Education (Ujoe)

UJOE Vol. 3 No 1 (JUNE, 2020) UNESWA JOURNAL OF EDUCATION (UJOE) An Online Journal of the Faculty of Education University of Eswatini Kwaluseni Campus. ISSN: 2616-301 UJOE Vol. 3 No 1 (JUNE, 2020) EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Prof.O. I. Oloyede Dean Education EDITOR Dr. P. Mthethwa MANAGING EDITORS Prof. I. Oloyede Prof. C. I. O. Okeke Dr. P. Mthethwa Dr. Y. Faremi Dr. R. Mafumbate Dr. K. Ntinda Dr. S.K. Thwala Ms M.S. Ngcobo. EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Prof. V. Chikoko (Educational Leadership), School of Education, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa. Dr. O. Pemede (Sociology of Education), Faculty of Education, Lagos State University, Lagos, Nigeria. Prof. M. Chitiyo (Special Education), Department Chair, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States of America. Dr. E. Mazibuko (History of Education), Examination Council of Eswatini. Prof. K.G. Karras (Education Studies), Faculty of Education, University of Crete, Gallos University Campus, Rethymno 74100, Crete, Greece. Prof. I. Oloyede (Science Education), Dept. of Curriculum & Teaching, Faculty of Education, University of Eswatini, Kwaluseni Campus, Eswatini. Prof. Z. Zhang (Teaching and Learning), College of Education and P-16 Integration, The University of Texas, Rio Grange Valley, Brownsville, United States of America. Prof. C. I. O. Okeke (Sociology of Education), Dept. of Educational Foundations & Management, Faculty of Education, University of Eswatini, Kwaluseni Campus, Eswatini. Prof. J.W. Badenhorst (Educational Psychology), Department of Postgraduate Studies, Central University of Technology, Welkom Campus, South Africa. Prof. A.B. Oduaran (Adult Education & Lifelong Learning), Faculty of Education, North-West University, Mmabatho 2735, South Africa. Dr. S.S.K. Thwala (Special Needs & Psychology of Education), Dept. -

Global Polio Surveillance Status Report

Global Polio Surveillance Status Report 2019 WHO/POLIO/19.08 Published by the World Health Organization (WHO) on behalf of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) © World Health Organization 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. Global Polio Surveillance Status Report, 2019.Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2019 (WHO/POLIO/19.08) Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris. Sales, rights and licensing. -

ESS9 Codebook

ESS9 Codebook ESS9 Codebook APPENDIX A7 ESS Codebook, ESS9-2018 ed. 3.1 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A7 Codebook (published 19.02.21): Changes from edition 3.0: Changes in country data: Croatia: F61 (ANCTRY1): Variable recoded for 14 cases to reflect updated bridging to ESS10 European standard classification of cultural and ethnic groups. F61 (ANCTRY2): Variable recoded for 25 cases to reflect updated bridging to ESS10 European standard classification of cultural and ethnic groups. Hungary: B38 (IMSMETN), B39 (IMDFETN): Variables for Hungary have been omitted from integrated file. (PSU): Variable for Hungary has been corrected. 1 of 535 ESS9 Codebook Country Items · cntry - Country cntry - Country Type Code Format 2 A2 Location 5 Question Country AT Austria BE Belgium BG Bulgaria CH Switzerland CY Cyprus CZ Czechia DE Germany DK Denmark EE Estonia ES Spain FI Finland FR France GB United Kingdom HR Croatia HU Hungary IE Ireland IS Iceland IT Italy LT Lithuania LV Latvia ME Montenegro NL Netherlands 2 of 535 ESS9 Codebook NO Norway PL Poland PT Portugal RS Serbia SE Sweden SI Slovenia SK Slovakia Weights Items · dweight - Design weight · pspwght - Post-stratification weight including design weight · pweight - Population size weight (must be combined with dweight or pspwght) · anweight - Analysis weight dweight - Design weight Type Numeric (Double), Weight Location R17 Question Design weight Measurement level 1 Nominal Format 21 F4.2 pspwght - Post-stratification weight including design weight Type Numeric (Double), Weight Location R18 Question -

12288288 01.Pdf

Ministry of Education and Training The Kingdom of Swaziland PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF SECONDARY SCHOOLS AIMED AT PROMOTING INCLUSIVE EDUCATION IN THE KINGDOM OF SWAZILAND MARCH 2017 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) MATSUDA CONSULTANTS INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. INTEM CONSULTING, INC. HM JR 17-044 Ministry of Education and Training The Kingdom of Swaziland PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF SECONDARY SCHOOLS AIMED AT PROMOTING INCLUSIVE EDUCATION IN THE KINGDOM OF SWAZILAND MARCH 2017 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) MATSUDA CONSULTANTS INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. INTEM CONSULTING, INC. Preface Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) decided to conduct the preparatory survey and entrust the survey to the Consortium of Matsuda Consultants International Co., Ltd. and INTEM Consulting, Inc. The survey team held a series of discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of the Kingdom of Swaziland, and conducted field investigations. As a result of further studies in Japan, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. Finaly, I wish to express my sinsere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of the Kingdom of Swaziland for their close cooperation contributed to the survey team. March, 2017 Akiko Kumagai Director General Human Development Department Japan International Cooperation Agency Summary 1 Outline of the Country Having gained independence from Great Britain in 1968, the Kingdom of Swaziland (hereinafter called “Swaziland”) is a landlocked country located on the southeastern tip of the African continent, neighbored by South Africa and Mozambique. -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All Africa People

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all Africa People Groups & Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups (LR-UPGs) Source: Joshua Project; www.joshuaproject.net To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all Africa People Groups & all LR-UPGs = Least-Reached--Unreached People Groups. 49 Africa countries & 9 islands & People Groups & LR-UPG are included. AFRICA SUMMARY: 3,713 total People Groups; 996 total Least-Reached--Unreached People Groups. Downloaded in August 2020 from www.joshuaproject.net LR-UPG defin: less than 2% Evangelical & less than 5% total Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. * * * Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country * * * "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" * * * Let's dream God's dreams, and fulfill God's visions -- God dreams of all people groups knowing & loving Him! * * * Revelation 7:9, "After this I looked and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. 3:15! * In the Great Commissions Jesus commands us to reach all peoples in the world, Matt. 28:19-20! * People without Jesus are eternally lost, & Jesus is the only One who can save them, John 14:6! * We have been given "the ministry & message of reconciliation", in Christ, 2 Cor. -

World Social Report 2021: Reconsidering Rural Development

World Social Report 2021 Reconsidering Rural Development WORLD SOCIAL REPORT 2021 Department of Economic and Social Affairs The World Social Report is a flagship publication of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). UN DESA is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department’s mission is to promote and support international cooperation in the pursuit of sustainable development for all. Its work is guided by the universal and transformative 2030 Agenda for Sus- tainable Development, along with a set of 17 integrated Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the United Nations General Assembly. UN DESA’s work addresses a range of crosscutting issues that affect peoples’ lives and livelihoods, such as social policy, poverty eradication, employment, social inclusion, inequalities, population, indigenous rights, macroeconomic policy, development finance and cooperation, public sector innovation, forest policy, climate change and sustainable development. United Nations publication Copyright © United Nations, 2021 All rights reserved ST/ESA/376 Sales no.: E.21.IV.2 ISBN: 978-92-1-130424-4 eISBN: 978-92-1-604062-8 Print ISSN: 2664-5467 Online ISSN: 2664-5475 2 FOREWORD Foreword The COVID-19 pandemic has caused immense suffering around the world. It has taken millions of lives, reversed decades of development progress, exacerbated gender inequality and made the task of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030 even more difficult. Through response and recovery efforts, however, opportunities exist to build a greener, more inclusive and resilient future. The experience of the pandemic has shown, for example, that where high-quality Internet connectivity is coupled with flexible working arrangements, many jobs that were traditionally considered to be urban can be performed in rural areas too. -

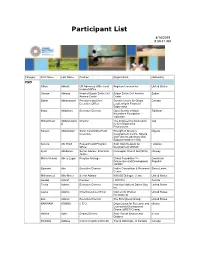

Participant List

Participant List 4/14/2019 8:59:41 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Osman Abbass Head of Sudan Sickle Cell Sudan Sickle Cell Anemia Sudan Anemia Center Center Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Ilhom Abdulloev Executive Director Open Society Institute Tajikistan Assistance Foundation - Tajikistan Mohammed Abdulmawjoo Director The Engineering Association Iraq d for Development & Environment Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Serena Abi Khalil Research and Program Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Officer Development (ANND) Kjetil Abildsnes Senior Adviser, Economic Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) Norway Justice Maria Victoria Abreu Lugar Program Manager Global Foundation for Dominican Democracy and Development Republic (GFDD) Edmond Abu Executive Director Native Consortium & Research Sierra Leone Center Mohammed Abu-Nimer Senior Advisor KAICIID Dialogue Centre United States Aouadi Achraf Founder I WATCH Tunisia Terica Adams Executive Director Hamilton National Dance Day United States Inc. Laurel Adams Chief Executive Officer Women for Women United States International Zoë Adams Executive Director The Strongheart Group United States BAKINAM ADAMU C E O Organization for Research and Ghana Community Development Ghana -

The Process of Mourning and Remarrying for Widowers in the Swazi Culture: a Pastoral Challenge

THE PROCESS OF MOURNING AND REMARRYING FOR WIDOWERS IN THE SWAZI CULTURE: A PASTORAL CHALLENGE THESIS BY: DALCY BADELI DLAMINI STUDENT NUMBER: 13394322 SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF PhD IN THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA SUPERVISOR: PROF M.J.S. MASANGO SEPTEMBER 2020 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the following: My parents: Walter Grant Nsibande (deceased) & Catherine Nsibande nee Seyama who worked tirelessly to see us through school. My one and only husband: Anthony Mfanaleni Dlamini. My loving Children: Lindokuhle and Alwandze Dlamini. My house keeper (A helper): Bethusile Mamba. St Michaels Chapel in Manzini 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For this accomplishment I give honour and glory to God the Creator, Redeemer and Sustainer. If God had not been by my side………I would not have completed this work. My gratitude goes to the following: - My coach and supervisor, Professor Maake Masango. Our journey began with my BA (Hons) and you gave me all the love, support and care a daughter may have asked. - Dr. Tshepo Masango Cherry, and Dr. Lesley Chery for stretching me the first day you met me for contact classes in Alex….It has surely come to pass and it’s for me as you said. - Mrs. Pauline Masango and her staff, for the love and support you poured to us as students the whole time we attended contact week. - To my colleagues in contact class, for the deliberations, constructive criticism and of courses the humor. Keep pushing. - To my one and only Anthony. You have been there for me through thick and thin. -

Religion and Development in Africa 25 Bible in Africa Studies

25 BiAS - Bible in Africa Studies Exploring Religion in Africa 4 Ezra Chitando, Masiiwa Ragies Gunda & Lovemore Togarasei (Eds.) RELIGION AND DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA 25 Bible in Africa Studies Études sur la Bible en Afrique Bibel-in-Afrika-Studien Exploring Religion in Africa 4 Bible in Africa Studies Études sur la Bible en Afrique Bibel-in-Afrika-Studien Volume 25 edited by Joachim Kügler, Lovemore Togarasei, Masiiwa R. Gunda In cooperation with Ezra Chitando and Nisbert Taringa (†) Exploring Religion in Africa 4 2020 Religion and Development in Africa edited by Ezra Chitando, Masiiwa Ragies Gunda & Lovemore Togarasei In cooperation with Joachim Kügler 2020 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Informationen sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Gedruckt mit Unterstützung von Dieses Werk ist als freie Onlineversion über das Forschungsinformationssys- tem (FIS; https://fs.uni-bamberg.de) der Universität Bamberg erreichbar. Das Werk – ausgenommen Cover und Zitate – steht unter der CC-Lizenz CCBY. Lizenzvertrag: Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 Herstellung und Druck: docupoint Magdeburg Umschlaggestaltung: University of Bamberg Press Umschlaggraphik und Deco-Graphiken: © Joachim Kügler Text-Formatierung: lrene Loch, Joachim Kügler © University of Bamberg Press, Bamberg 2020 http://www.uni-bamberg.de/ubp ISSN: 2190-4944 ISBN: 978-3-86309-735-6 (Druckausgabe) eISBN: 978-3-86309-736-3 (Online-Ausgabe) URN: urn:nbn:de:bvb:473-irb-477591 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20378/irb-47759 DEDICATION In Memory of Our Founding ERA Co-editor And Beloved Colleague NISBERT T. -

Amnesty International

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL Amnesty International is a movement of 10 million people which mobilizes the humanity in everyone and campaigns for change so we can all enjoy our human rights. Our vision is of a world where those in power keep their promises, respect international law and are held to account. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and individual donations. We believe that acting in solidarity and compassion with people everywhere can change our societies for the better. Amnesty International is impartial. We take no position on issues of sovereignty, territorial disputes or international political or legal arrangements that might be adopted to implement the right to self- determination. This report is organized according to the countries we monitored during the year. In general, they are independent states that are accountable for the human rights situation on their territory. First published in 2021 by Except where otherwise noted, This report documents Amnesty Amnesty International Ltd content in this document is Internationalos work and Peter Benenson House, licensed under a concerns through 2020. 1, Easton Street, CreativeCommons (attribution, The absence of an entry in this London WC1X 0DW non-commercial, no derivatives, report on a particular country or United Kingdom international 4.0) licence. territory does not imply that no https://creativecommons.org/ © Amnesty International 2021 human rights violations of licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode concern to Amnesty International IndeZ|P1L 102022021 For more information please visit have taken place there during ISB0|021001 the permissions page on our the year.