Assessing State Strategies for Health Coverage Expansion: Case Studies of Oregon, Rhode Island, New Jersey, and Georgia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Health Plan Changes Effective January 1, 2017

HEALTH SYSTEMS DIVISION Kate Brown, Governor 500 Summer St NE E44 Salem, OR, 97301 Date: December 8, 2016 Voice: 1-800-336-6016 FAX: 503-945-6873 To: Oregon Health Plan providers TTY: 711 www.oregon.gov/OHA/healthplan From: Don Ross, Physical and Oral Health Programs manager Integrated Health Programs, Health Systems Division Subject: Oregon Health Plan changes effective January 1, 2017 To meet federal health plan requirements, the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) is making the following changes to Oregon Health Plan (OHP) benefits and copayment requirements, subject to approval by the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The changes apply to services covered by OHA and all coordinated care organizations on and after January 1, 2017. OHP Plus benefit changes OHA will update the Prioritized List of Health Services and related administrative rules to add these benefits effective January 1, 2017: A wig benefit of at least $150 per year for patients with hair loss related to chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Separate limits for habilitative and rehabilitative services under Guideline Note 6, which covers physical, occupational and speech therapy for adults with physical health conditions. Guideline Note 106 on Preventive Services has been modified to reflect that OHP coverage will continue to follow federal requirements for coverage of preventive services including: Services with A and B recommendations from the United States Preventive Services Task Force, Immunizations recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, The Health Resources & Services Administration’s Women’s Preventive Services guidelines, and The American Academy of Pediatrics Bright Futures Guidelines. Removal of OHP copayments Copays will be removed from all OHP services, including pharmacy, professional, and outpatient hospital services. -

Prioritization of Health Services

PRIORITIZATION OF HEALTH SERVICES A Report to the Governor and the 72nd Oregon Legislative Assembly Oregon Health Services Commission Office for Oregon Health Policy and Research Department of Administrative Services 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables . iii Health Services Commission and Staff . .v Acknowledgments . .vii Executive Summary . xi CHAPTER ONE: HISTORY OF THE OREGON HEALTH PLAN Legislative Framework . 3 Implementation of the Medicaid Demonstration . .. 5 Accomplishments . 7 CHAPTER TWO: PRIORITIZATION OF HEALTH SERVICES Charge to the Health Services Commission . .. 21 Prioritization Methodology . 22 Biennial Review . 23 Interim Modifications . 31 Technical Changes . 32 Advancements in Medical Technology . .33 Solid Organ Transplantation . 34 Intrathecal Baclofen Therapy . 36 CHAPTER THREE: CLARIFICATIONS TO THE PRIORITIZED LIST OF HEALTH SERVICES Practice Guidelines . 39 Hysterectomy for Benign Conditions . 40 Adenomyosis . 42 Comfort Care . 44 Spinal Deformities . 45 Cancer of the Esophagus, Liver, Pancreas, and Gallbladder . 45 Intrathecal Baclofen Therapy . 46 Prevention Guidelines . 47 Coding Specifications . 48 Seminoma . 48 Breast Reconstruction Post-Mastectomy for Breast Cancer . 49 Statements of Intent . 49 Medical Codes Not Appearing on the Prioritized List . 50 CHAPTER FOUR: SUBCOMMITTEES, TASK FORCES, AND WORKGROUPS Health Outcomes Subcommittee . 55 Mental Health Care and Chemical Dependency Subcommittee . 56 Workgroup on Public Outreach . 57 Oncology Task Force . 58 CHAPTER FIVE: RECOMMENDATIONS . .61 i TABLE -

Oregon Health Plan

Background Brief on… Oregon Health Plan Prepared by: Rick Berkobien May 2004 Background Volume 2, Issue 1 From 1989 to 1999, the Oregon Legislature passed a series of laws collectively known as the Oregon Health Plan (OHP). OHP expanded access to health care using a combi- Inside this Brief nation of public and private insurance plans and a prioritized list of health care services. Currently, more than 450,000 • Background Oregonians have access to health care under the OHP. The Department of Human Services (DHS), Office of Medi- • OHP Plus cal Assistance Programs (OMAP) administers the public insurance components of OHP, including Medicaid and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). SCHIP • OHP Standard is a separate federal/state funded program to provide health care services to certain low-income children. • Family Health Insurance The Family Health Insurance Assistance Program (FHIAP), Assistance Program created by the 1997 Legislature, provides subsidies for the purchase of private health insurance by low-income workers. As part of OHP, FHIAP is currently funded solely with state • Proof for OHP Eligibility dollars—about $20 million in tobacco settlement funds—and the number of people served is capped at around 4,000. FHIAP currently provides services to people with incomes • The Insurance Pool up to 170 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). Subsi- Governing Board dies range from 70 percent up to 95 percent of the premium costs depending on family size and income. • Staff and Agency Contacts House Bill 2519 (2001) modified the program to provide coverage to more uninsured Oregonians, have more flexibil- ity in the program’s benefits, secure more federal dollars, and help control the program’s rising medical costs. -

Application for Oregon Health Plan and Healthy Kids

Application for Oregon Health Plan and Healthy Kids Read this before you start. You can get this application in other formats. • This is for the Oregon Health Plan and Healthy Kids. You • This document can be provided upon request in alternative can apply for one or both programs with this application. formats for individuals with disabilities. Other formats may • Please answer all questions so we have the information include (but are not limited to) large print, Braille, audio we need to see if you qualify. recordings, Web-based communications and other electronic formats. Email [email protected], or call • Read the Green Booklet by clicking here. 1-800-699-9075 (voice) or TTY 711 to arrange for the It includes more information about the questions asked. alternative format that will work best for you. When you see this arrow, it means you may have to • You can get this application in another language or you send documents that show us the information you gave can get an interpreter. Call 1-800-699-9075 or TTY 711. is correct. Please mail copies of these documents along with your application to: For more information about: OHP Processing Center, • Healthy Kids or to find local application assistance, PO Box 14520, Salem, OR 97309-5044 click here: www.oregonhealthykids.gov or fax to 503-373-7493 • Oregon Health Plan, click here: www.oregon.gov/OHA/healthplan 1 About you. Please tell us about yourself, even if you are only applying for benefits for your children. You may need to send proof of immigration status or tribal affiliation if you are applying for yourself (see the checklist on page 16). -

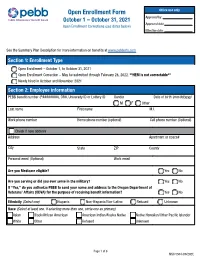

MSC 5504 PEBB Open Enrollment and Correction Form

Open Enrollment Form Office use only October 1 – October 31, 2021 Approved by: Approved date: Open Enrollment Corrections (see dates below) Effective date: See the Summary Plan Description for more information on benefits at www.pebbinfo.com Section 1: Enrollment Type F Open Enrollment – October 1, to October 31, 2021 F Open Enrollment Correction – May be submitted through February 28, 2022. **HEM is not correctable** F Newly hired in October and November 2021 Section 2: Employee information PEBB benefit number (P########), OR#, University ID or Lottery ID Gender Date of birth (mm/dd/yyyy) F M F F F Other Last name First name M.I. Work phone number Home phone number (optional) Cell phone number (Optional) F Check if new address Address Apartment or space# City State ZIP County Personal email (Optional) Work email Are you Medicare eligible? F Yes F No Are you serving or did you ever serve in the military? F Yes F No If “Yes,” do you authorize PEBB to send your name and address to the Oregon Department of Veterans’ Affairs (ODVA) for the purpose of receiving benefit information? F Yes F No Ethnicity (Select one): F Hispanic F Non-Hispanic/Non-Latino F Refused F Unknown Race (Select at least one. If selecting more than one, circle one as primary): F Asian F Black/African American F American Indian/Alaska Native F Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander F White F Other F Refused F Unknown Page 1 of 8 MSC 5504 (09/2021) Section 3: Dependent information 1. List all eligible family members you want to provide coverage for. -

Oregon Health Plan (OHP) Is a State Program That Provides Health Care Coverage to Eligible Clients

Oregon Health Plan Client Handbook Department of Human Services October 2004 ii Accessible Services Communicating with Us Do you have a disability that makes it hard for you to read printed material? Do you speak a language other than English? We can give you information in one of several ways: Large print Audio tape Braille Computer disk Oral presentation (face-to-face or on the phone) Sign language interpreter Translations in other languages Let us know what you need. Tell your worker or, if you have no case worker, call 503-373-0333 x 393 or TTY 503-373-7800. Is Access a Problem? Do barriers in buildings or transportation make it hard for you to a� end meetings? To get state services? We can move our services to a more accessible place. We can provide the type of transportation that works for you. iii You Have a Right to Complain You can complain if: You keep ge� ing DHS printed forms and notices, but you need them some other way. Our programs aren’t accessible. You have 60 days to make your complaint. Send your complaint to: The Governor's Advocacy Offi ce 500 Summer St NE, E17 Salem, OR 97301 1-800-442-5238 1-800-945-6214 TTY 503-378-6532 Fax -or- US Dept of Health & Human Services Offi ce for Civil Rights 2201 Sixth Avenue, Mail Stop RX-11 Sea� le, WA 98121 1-800-362-1710 1-206-615-2296 TTY 1-206-615-2297 Fax [email protected] iv Contents Welcome to the Oregon Health Plan ............................................1 Prioritized List of Health Services ..........................................2 OHP Terms and Defi nitions -

FAQ: Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome (HBOC)

Patient FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome February 2018 PUBLIC HEALTH Screenwise Table of Contents What is hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome? .......3 Why is it important to know if my cancer was hereditary? ...................3 How do I find out if I have a hereditary cancer syndrome? ...................4 Personal and family history of cancer can be a sign of HBOC. ..............5 Where can I find a board-certified cancer genetic specialist? .............6 Will my health coverage pay for genetic counseling and testing? .......8 What are the BRCA genes? .....................................................................8 What if I don’t have coverage to pay for genetic counseling and testing? ..........................................................................9 Genetic privacy and anti-discrimination laws. .......................................9 What can I do to lower my risk for getting breast cancer and other cancers? ...............................................................................10 What is hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome? HBOC stands for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Having HBOC does not mean that you have cancer, or that you will get cancer. Having HBOC means that you may have an increased risk for certain types of cancer. It also means that some of these cancers may run in your family, passing from generation to generation. • Women with HBOC are more likely to develop cancers, such as breast and ovarian cancer, than women without HBOC. • Men with HBOC are more likely to develop cancers, such as breast and prostate cancer, than men without HBOC. NOTE: HBOC can pass from either parent. Therefore, it is important to know as much as you can about your family health history on both sides. -

Waiver Renewal Application to CMS, August 2016

Application for Renewal and Amendment Oregon Health Plan 1115 Demonstration Project Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program Submitted: August 12, 2016 Oregon Health Plan – Project Numbers 11-W-00160/10 & 21-W-00013/10 | 0 Table of Contents RENEWAL AND AMENDMENT REQUEST Topic Page I. Program Description 2 II. Demonstration Eligibility 57 III. Demonstration Benefits and Cost Sharing Requirements 61 IV. Delivery System and Payment Rates for Services 65 V. Implementation of Demonstration 68 VI. Public Notice and Comment Process 69 VII. Federal Authority Requests: Proposed Waiver and Expenditure Authorities 77 VIII. Financing and Budget Neutrality 81 IX. Evaluation 84 X. Demonstration Administration 98 APPENDICES Appendix A: Support for Health System Transformation 99 Appendix B: Quality Strategy 125 Appendix C: Measurement Strategy 141 Appendix D: Concept Paper on Increasing Use of Health-Related Services and 174 Value-Based Payments Appendix E: Integrating Health Care Delivery for Individuals Eligible for Both 180 Medicare and Medicaid Appendix F: Federal Authority to Continue and Enhance Oregon’s Health Care 183 Transformation Appendix G: Budget Neutrality Summary 192 Appendix H: Budget Neutrality: Projection of Expenditures for the Title XIX 194 Program Demonstration Years 2011–2020 Appendix I: Title XXI Allotment 198 Appendix J: Public Meeting Notices 201 Appendix K: Stakeholder Survey and Public Comment Logs 211 1 | Oregon Health Plan – Project Numbers 11-W-00160/10 & 21-W-00013/10 I. Program Description The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) granted Oregon its initial section 1115 demonstration waiver to implement the innovative Oregon Health Plan (OHP) more than two decades ago, phasing in coverage under the initial demonstration beginning in 1994. -

Oregon's Medicaid

kaiser commission on medicaid and the uninsured Oregon’s Medicaid PDL: Will an Evidence- Based Formulary with Voluntary Compliance Set a Precedent for Medicaid? Prepared by: Cathy Bernasek Dan Mendelson Ryan Padrez Catherine Harrington, PharmD The Health Strategies Consultancy LLC January 2004 kaiser commission medicaid and the uninsured The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured provides information and analysis on health care coverage and access for the low-income population, with a special focus on Medicaid’s role and coverage of the uninsured. Begun in 1991 and based in the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Washington, DC office, the Commission is the largest operating program of the Foundation. The Commission’s work is conducted by Foundation staff under the guidance of a bi- partisan group of national leaders and experts in health care and public policy. James R. Tallon Chairman Diane Rowland, Sc.D. Executive Director Oregon’s Medicaid PDL: Will an Evidence- Based Formulary with Voluntary Compliance Set a Precedent for Medicaid? Prepared by: Cathy Bernasek Dan Mendelson Ryan Padrez Catherine Harrington, PharmD The Health Strategies Consultancy LLC January 2004 Table of Contents ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………...i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY…………………………………………………………….iii INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………….…1 BACKGROUND ON MEDICAID IN OREGON……………………………………..4 AUTHORIZATION OF OREGON’S PREFERRED DRUG LIST……………….…5 OREGON’S PRACTITIONER-MANAGED PRESCRIPTION DRUG PLAN…….7 PERSPECTIVES ON OREGON’S PRACTITIONER-MANAGED PRESCRIPTION DRUG PLAN……………………………………………….15 -

Oregon Health Plan Application

Application for Oregon Health Plan Coverage Need help with this Get expert help at no cost from a certified insurance agent, community application? partner or customer service representative: • Visit www.OregonHealthCare.gov to find agents and community partners who can help you apply. • Call OHP Customer Service at 1-800-699-9075 to get help or to request a list of agents and community partners in your area. You can ask for help in a different language, too. Information you will You will need the following information for everyone in your household: need to provide on • Social Security number for everyone who has one and is applying this application: • Alien Resident number for everyone who has one and is applying (you may qualify even if you don’t have one) • Birth dates • Income and deductions (for example, from pay stubs or W-2 forms) • Information about health insurance available to you through an employer AFTER COMPLETING YOUR APPLICATION MAIL OR FAX TO: Mail: Fax: OHP Customer Service 503-378-5628 P.O. Box 14015 Salem, OR 97309-5032 Be sure to fill out all necessary pages and SIGN your application before sending. OFFICIAL USE ONLY Date of request Received Program Branch Case no. Worker ID Case name Route to Prime no. SSN App status Office use OHA 7210 (Rev 09/16) How do we use First we’ll ask some basic questions about each person. Then we’ll ask about your information? income, current health insurance, disabilities and Tribal ancestry. We’ll keep all the information you provide private, as required by law. -

1Of 2 Voters' Pamphlet Measures

1of 2 Voters’ Pamphlet Measures Oregon General Election November 4, 2008 Bill Bradbury Oregon Secretary of State This Voters’ Pamphlet is provided for assistance in casting your vote by mail ballot. OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE ELECTIONS DIVISION BILL BRADBURY JOHN LINDBACK DIRECTOR SECRETARY OF STATE 255 CAPITOL ST NE, SUITE 501 JEAN STRAIGHT SALEM, OREGON 97310 DEPUTY SECRETARY OF STATE (503) 986-1518 My Fellow Oregonians: It’s time once again for Oregon voters to step up and do our part for democracy. It’s time to vote. We honor the Americans who have died over the years to keep us free and preserve this cherished right to vote. But their sacrifice is even more heartening when we see repressed people from around the world waiting in line for hours, even days, to exercise this right we sometimes take for granted. And here in Oregon, we have work to do. Once again, the ballot will ask us to consider statewide measures dealing with taxes, property, education and other matters. There are 12 of them, four placed on the ballot by the Legislature and eight by citizen initiative. In the pages that follow, you will see arguments for and against these measures as written by their supporters and opponents. Please read them and think carefully. What we decide as voters will have a huge impact on the state and our pocketbooks. Voting offers power, the power to have a say in the policies and priorities that will govern your city, your county, your state and your nation in the years ahead. -

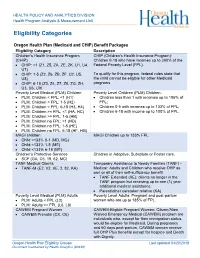

Eligibility Categories

HEALTH POLICY AND ANALYTICS DIVISION Health Program Analysis & Measurement Unit Eligibility Categories Oregon Health Plan (Medicaid and CHIP) Benefit Packages Eligibility Category Description Children's Health Insurance Program CHIP (Children's Health Insurance Program): (CHIP) Children 0-18 who have incomes up to 300% of the • CHIP: <1 (Z1, Z5, ZA, ZE, ZK, U1, U4, Federal Poverty Level (FPL). U7) • CHIP: 1-5 (Z2, Z6, ZB, ZF, U2, U5, To qualify for this program, federal rules state that U8) the child cannot be eligible for other Medicaid • CHIP: 6-18 (Z3, Z4, Z7, Z8, ZG, ZH, programs. U3, U6, U9) Poverty Level Medical (PLM) Children Poverty Level Children (PLM) Children: • PLM: Children < FPL: <1 (H1) • Children less than 1 with incomes up to 185% of • PLM: Children < FPL: 1-5 (H2) FPL; • PLM: Children < FPL: 6-18 (H3, H4) • Children 0-5 with incomes up to 133% of FPL; • PLM: Children >= FPL: <1 (HA, HC) • Children 6-18 with income up to 100% of FPL. • PLM: Children >= FPL: 1-5 (HB) • PLM: Children no FPL: <1 (HD) • PLM: Children no FPL: 1-5 (HE) • PLM: Children no FPL: 6-18 (HF, HG) MAGI children MAGI Children up to 133% FPL • Child <133% 0-1 (MD, MG) • Child <133% 1-5 (ME) • Child <133% 6-18 (MF) Children's Protective Services Children in Adoptive, Substitute or Foster care. • SCF (GA, C5, 19, 62, MC) TANF Medical Clients Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) - • TANF-M (E2, V2, XE, 2, 82, KA) Medical: Adults and Children who receive OHP as part or all of their self-sufficiency benefit.