Socrates: “Those Who Are Hardest to Love Need It the Most.” by Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jane Fonda Blisters Vietnam War Effort

=11 Book Talk Fonda A re-play of the Jane Fonda Dr. Arlene Akerlund, assis- speech delivered at SJS tant professor of English, yesterday in the C.U. Ball- will discuss Ernest Heming- room will be on radio station way's novel "Islands in the KSJS 90.7 tonight at 8 and on Stream," today at noon in station KSJO at 8 tomorrow rooms A and B of the Spartan artan Datil Cafeteria. night. Serving the San Jose State College Community Since 1934 Vol. 58 SAN JOSE CALIFORNIA 95114, WEDNESDAY MARCH 3, 1971 No 77 Jane Fonda Blisters #1$ Vietnam War Effort kkitellompoiffatielt" By LANCE FREDERIKSEN "You don't hear of this because we do have lost control of their forces. Daily Political Writer not have a responsible press. But let me "If the men get a gung-ho officer, 111 q - Jane Fonda, actress and anti-war assure you, MyLai is not an isolated they'll fragg him," she declared, "So activist, urged an overflow crowd of incident," Miss Fonda added. the officers won't make them cut their .,A.0044 . about 2,000 listeners yesterday after- Miss Fonda recently attended the hair, stop smoking dope, or, above all, noon in the College Union Ballroom to war crimes investigation sponsored by go on dangerous missions." "make peace with the people of Viet- the Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Fragging, Miss Fonda explained, :Iv nam." The meeting, held in Detroit, Jan. 31, occurs when a fragmentation bomb is The audience enthusiastically and Feb. 1-2, was organized by 2,000 ex- rolled under an officer's tent. -

'Ex-Lexes' Cherished Time on Hawaiian Room's Stage POSTED: 01:30 A.M

http://www.staradvertiser.com/businesspremium/20120622__ExLexes_cherished_time_on_Hawaiian_Rooms_stage.html?id=159968985 'Ex-Lexes' cherished time on Hawaiian Room's stage POSTED: 01:30 a.m. HST, Jun 22, 2012 StarAdvertiser.com Last week, we looked at the Hawaiian Room at the Lexington Hotel in New York City, which opened 75 years ago this week in 1937. The room was lush with palm trees, bamboo, tapa, coconuts and even sported a periodic tropical rainstorm, said Greg Traynor, who visited with his family in 1940. The Hawaiian entertainers were the best in the world. The Hawaiian Room was so successful it created a wave of South Seas bars and restaurants that swept the country after World War II. In this column, we'll hear from some of the women who sang and danced there. They call themselves Ex-Lexes. courtesy Mona Joy Lum, Hula Preservation Society / 1957Some of the singers and dancers at the Hawaiian Room in the Lexington Hotel. The women relished the opportunity to "Singing at the Hawaiian Room was the high point of my life," perform on such a marquee stage. said soprano Mona Joy Lum. "I told my mother, if I could sing on a big stage in New York, I would be happy. And I got to do that." Lum said the Hawaiian Room was filled every night. "It could hold about 150 patrons. There were two shows a night and the club was open until 2 a.m. I worked an hour a day and was paid $150 a week (about $1,200 a week today). It was wonderful. -

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Leslie Caron

COUNCIL FILE NO. t)q .~~f7:; COUNCIL DISTRICT NO. 13 APPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING DIRECT TO CITY COUNCIL The attached Council File may be processed directly to Council pursuant to the procedure approved June 26, 1990, (CF 83-1075-81) without being referred to the Public Works Committee because the action on the file checked below is deemed to be routine and/or administrative in nature: -} A. Future Street Acceptance. -} B. Quitclaim of Easement(s). -} C. Dedication of Easement(s). -} D. Release of Restriction(s) . ..10 E. Request for Star in Hollywood Walk of Fame. -} F. Brass Plaque(s) in San Pedro Sport Walk. -} G. Resolution to Vacate or Ordinance submitted in response to Council action. -} H. Approval of plans/specifications submitted by Los Angeles County Flood Control District. APPROVAL/DISAPPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING: APPROVED DISAPPROVED* Council Office of the District Public Works Committee Chairperson 'DISAPPROVED FILES WILL BE REFERRED TO THE PUBLIC WORKS COMMITTEE. Please return to Council Index Section, Room 615 City Hall City Clerk Processing: Date notice and report copy mailed to interested parties advising of Council date for this item. Date scheduled in Council. AFTER COUNCIL ACTION: ___ -f} Send copy of adopted report to the Real Estate Section, Development Services Division, Bureau of Engineering (Mail Stop No. 515) for further processing. __ ---J} Other: . .;~ ';, PLEASE DO NOT DETACH THIS APPROVAL SHEET FROM THE COUNCIL FILE ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS - E Office of the City Engineer Los Angeles California To the Honorable Council Of the City of Los Angeles NOV 242009 Honorable Members: C. D. No. 13 SUBJECT: Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street - Walk of Fame Additional Name in Terrazzo Sidewalk- LESLIE CARON RECOMMENDATIONS: A. -

HOLLYWOOD – the Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition

HOLLYWOOD – The Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition Paramount MGM 20th Century – Fox Warner Bros RKO Hollywood Oligopoly • Big 5 control first run theaters • Theater chains regional • Theaters required 100+ films/year • Big 5 share films to fill screens • Little 3 supply “B” films Hollywood Major • Producer Distributor Exhibitor • Distribution & Exhibition New York based • New York HQ determines budget, type & quantity of films Hollywood Studio • Hollywood production lots, backlots & ranches • Studio Boss • Head of Production • Story Dept Hollywood Star • Star System • Long Term Option Contract • Publicity Dept Paramount • Adolph Zukor • 1912- Famous Players • 1914- Hodkinson & Paramount • 1916– FP & Paramount merge • Producer Jesse Lasky • Director Cecil B. DeMille • Pickford, Fairbanks, Valentino • 1933- Receivership • 1936-1964 Pres.Barney Balaban • Studio Boss Y. Frank Freeman • 1966- Gulf & Western Paramount Theaters • Chicago, mid West • South • New England • Canada • Paramount Studios: Hollywood Paramount Directors Ernst Lubitsch 1892-1947 • 1926 So This Is Paris (WB) • 1929 The Love Parade • 1932 One Hour With You • 1932 Trouble in Paradise • 1933 Design for Living • 1939 Ninotchka (MGM) • 1940 The Shop Around the Corner (MGM Cecil B. DeMille 1881-1959 • 1914 THE SQUAW MAN • 1915 THE CHEAT • 1920 WHY CHANGE YOUR WIFE • 1923 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS • 1927 KING OF KINGS • 1934 CLEOPATRA • 1949 SAMSON & DELILAH • 1952 THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH • 1955 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS Paramount Directors Josef von Sternberg 1894-1969 • 1927 -

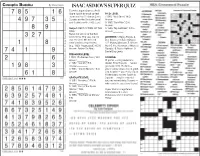

Isaac Asimov's Super Quiz

PAGE 6A WEDNESDAY, JULY 7, 2021 TIMES WEST VIRGINIAN ADVICE Dear Mayo Clinic Q and A: Simplify health Annie Annie Lane goals for success Syndicated Columnist that includes things such as: every other day with a meal. This can be By Cynthia Weiss – Ridding homes of any desserts, candy, something you can easily manage and Mayo Clinic News Network soda and processed food. feel successful with. Just remember not Dear Mayo Clinic: I am a mom of three – Promising to buy and eat only whole to overload it with dressing. Or instead of kids under 10, and I have struggled with foods made from scratch. grabbing a handful of chips for a snack, Twin brothers weight loss for years. I am challenged – Going to the gym five or more days a grab an apple or a cheese stick. Consider the between family and work obligations to week and working out for an hour each time. same substitutions for your children so you maintain a healthy lifestyle. I always start – Hiring a life coach to help get their life won’t be tempted. can’t get along off strong, but then I get overwhelmed and together. Over time, one change will lead to stop. Last month, despite trying to eat right – Reducing work stress. another. As you implement healthy things Dear Annie: I come from a big family. I and working out daily, I gained weight after Does this sound familiar? into your routine, you will build more have seven brothers and two sisters, and I’m two weeks instead of losing it. -

ATINER's Conference Paper Series HUM2014-0814

ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: HUM2014-0814 Athens Institute for Education and Research ATINER ATINER's Conference Paper Series HUM2014-0814 Iconic Bodies/Exotic Pinups: The Mystique of Rita Hayworth and Zarah Leander Galina Bakhtiarova Associate Professor Western Connecticut State University USA 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: HUM2014-0814 Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10671 Athens, Greece Tel: + 30 210 3634210 Fax: + 30 210 3634209 Email: [email protected] URL: www.atiner.gr URL Conference Papers Series: www.atiner.gr/papers.htm Printed in Athens, Greece by the Athens Institute for Education and Research. All rights reserved. Reproduction is allowed for non-commercial purposes if the source is fully acknowledged. ISSN 2241-2891 22/1/2014 2 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: HUM2014-0814 An Introduction to ATINER's Conference Paper Series ATINER started to publish this conference papers series in 2012. It includes only the papers submitted for publication after they were presented at one of the conferences organized by our Institute every year. The papers published in the series have not been refereed and are published as they were submitted by the author. The series serves two purposes. First, we want to disseminate the information as fast as possible. Second, by doing so, the authors can receive comments useful to revise their papers before they are considered for publication in one of ATINER's books, following our standard procedures of a blind review. Dr. Gregory T. Papanikos President Athens Institute for Education and Research 3 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: HUM2014-0814 This paper should be cited as follows: Bakhtiarova, G. -

744 101St Chase and Sandborn Show Anniversary Show

744 101ST CHASE AND SANDBORN SHOW ANNIVERSARY SHOW NBC 60 EX COM 5008 10-2-4 RANCH #153 1ST SONG HOME ON THE RANGE CBS 15 EX COM 5009 10-2-4 RANCH #154 1ST SONG UNTITLED SONG CBS 15 EX COM 5010 10-2-4 RANCH #155 1ST SONG BY THE SONS OF THE PIONEERS CBS 15 EX COM 5011 10-2-4 RANCH #156 1ST SONG KEEP AN EYE ON YOUR HEART CBS 15 EX COM 2951 15 MINUTES WITH BING CROSBY #1 1ST SONG JUST ONE MORE CHANCE 9/2/1931 8 VG SYN 4068 1949 HEART FUND THE PHIL HARRIS-ALICE FAYE SHOW 00/00/1949 15 VG COM 588 20 QUESTIONS 4/6/1946 30 VG- 246 20 QUESTIONS #135 12/1/48 AFRS 30 VG AFRS 247 20 QUESTIONS #137 1/8/1949 AFRS 30 VG AFRS 592 20 QUESTIONS WET HEN MUT. 30 VG- 2307 2000 PLUS THE ROCKET AND THE SKULL 30 VG- SYN 2308 2000 PLUS A VETRAN COMES HOME 30 VG- SYN 4069 A & P GYPSIES 1ST SONG IT'S JUST A MEMORY 00/00/1933 NBC 37 VG+ 1017 A CHRISTMAS PLAY #325 THESE THE HUMBLE (SCRATCHY) 30 G-VG SYN 2003 A DATE WITH JUDY WITH JOSEPH COTTON 2/6/1945 NBC 30 VG COM 938 A DATE WITH JUDY #86 WITH CHARLES BOYER AFRS 30 VG AFRS 2488 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH MARLENA DETRICH 10/15/1942 NBC 30 VG+ COM 2489 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH LUCILLE BALL 11/18/1943 NBC 30 VG+ COM 4071 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH LYNN BARI 12/16/1943 NBC 30 VG COM 4072 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH THE ANDREW SISTERS 12/26/1943 NBC 30 VG COM 2490 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH BERT GORDON 12/30/1943 NBC 30 VG+ COM 2491 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH JUDY GARLAND 1/6/1944 NBC 30 VG+ COM 2492 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH HAROLD PERRY 1/20/1944 NBC 30 VG+ COM 4073 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH THE GREAT GILDERSLEEVE 1/20/1944 NBC -

Power and Paranoia

Power and Paranoia: The Literature and Culture of the American Forties Course instructor: PD Dr. Stefan Brandt Ruhr-Universität Bochum Winter term 2009/10 Bibliography (selection) “A Life Round Table on the Pursuit of Happiness” (1948) Life 12 July: 95-113. Allen, Donald M., ed. The New American Poetry, 1945-1960. New York: Grove Press, 1960. “Anatomic Bomb: Starlet Linda Christians brings the new atomic age to Hollywood” (1945) Life 3 Sept.: 53. Asimov, Isaac. “Robbie.” [Originally published as “Strange Playfellow” in 1940]. In: I, Robot. New York: Gnome Press, 1950. 17-40. ---. “Runaround.” [1942]. In: I, Robot, 41-62. Auden, W.H. The Age of Anxiety: A Baroque Eclogue. New York: Random House, 1947. Auster, Albert, and Leonard Quart. American Film and Society Since 1945. London and Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1984. Balio, Tino. The American Film Industry. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1976. Barson, Michael, and Steven Heller. Red Scared: The Commie Menace in Propaganda and Popular Culture. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2001. Behlmer, Rudy, ed. Inside Warner Brothers 1935-1951. New York: Viking, 1985. Belfrage, Cedric. The American Inquisition: 1945-1960. Indianapolis and New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1973. Berman, Greta, and Jeffrey Wechsler. Realism and Realities: The Other Side of American Painting, 1940-1960. An Exhibition and Catalogue. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers Univ. Art Gallery, State Univ. of New Jersey, 1981. Birdwell, Michael E. Celluloid Soldiers: The Warner Bros. Campaign Against Nazism. New York: New York University Press, 1999. Boddy, William. “Building the World’s Largest Advertising Medium: CBS and Tele- vision, 1940-60.” In: Balio, ed., Hollywood in the Age of Television, 1990. -

George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5s2006kz No online items George P. Johnson Negro Film Collection LSC.1042 Finding aid prepared by Hilda Bohem; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 November 2. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections George P. Johnson Negro Film LSC.1042 1 Collection LSC.1042 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: George P. Johnson Negro Film collection Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1042 Physical Description: 35.5 Linear Feet(71 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1916-1977 Abstract: George Perry Johnson (1885-1977) was a writer, producer, and distributor for the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23). After the company closed, he established and ran the Pacific Coast News Bureau for the dissemination of Negro news of national importance (1923-27). He started the Negro in film collection about the time he started working for Lincoln. The collection consists of newspaper clippings, photographs, publicity material, posters, correspondence, and business records related to early Black film companies, Black films, films with Black casts, and Black musicians, sports figures and entertainers. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: English . Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Portions of this collection are available on microfilm (12 reels) in UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Gilda's Gowns Rachel Ann Wise

AWE (A Woman’s Experience) Volume 1 Article 10 1-1-2013 Gilda's Gowns Rachel Ann Wise Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/awe Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wise, Rachel Ann (2013) "Gilda's Gowns," AWE (A Woman’s Experience): Vol. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/awe/vol1/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in AWE (A Woman’s Experience) by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Gilda's Gowns Fashioning the Femme Fatale in Film Noir Rachel Anne Wise The 1940s brought the rise of a cynical, nihilistic film form in America, stereo typically characterized by its hardboiled detective crime plot starring a dominat ing female adorned in a black slinky dress with a pistol in her purse, seducing men and masterminding plots of cruelty and greed. This genre, film noir, grew out of the ashes of post-WWII America, lasting through the 19 50s and satisfying the growing market for pessimistic and violent thrillers. 1 Film noir has generated much scholarship since its mid-century inception, particularly for feminists, with the landmark publication of Laura Mulvey's 197 5 "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema," an article that analyzed the male gaze, explicit voyeuristic elements, and inherent misogyny within the genre. Using a Freudian and Lacanian lens, she claimed that the femme fatale character, or "fatal woman," symbolized the ominous threat of castration.