Chapter 2 Apocalypticism, Chiliasm, and Cultural Progress: Jerusalem in Early Modern Storyworlds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June/Sept 2014

Lutheran Synod Quarterly VOLUME 54 • NUMBERS 2–3 JUNE–SEPTEMBER 2014 All Have the Law But Fail: An Exegesis of Romans 2 with a Special Emphasis on Verses 14–16 Two Kingdoms: Simul iustus et peccator: Depoliticizing the Two Kingdoms Doctrine The Timeless Word Meets the 21st-Century World Koren’s Pastoral Letter Book Reviews The journal of Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary ISSN: 0360-9685 Lutheran Synod Quarterly VOLUME 54 • NUMBERS 2–3 JUNE–SEPTEMBER 2014 Te journal of Bethany Lutheran Teological Seminary lutheran Synod Quarterly EDITOR-IN-CHIEF........................................................... Gaylin R. Schmeling BOOK REVIEW EDITOR ......................................................... Michael K. Smith LAYOUT EDITOR ................................................................. Daniel J. Hartwig PRINTER ......................................................... Books of the Way of the Lord The Lutheran Synod Quarterly (ISSN: 0360-9685) is edited by the faculty of Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary 6 Browns Court Mankato, Minnesota 56001 The Lutheran Synod Quarterly is a continuation of the Clergy Bulletin (1941–1960). The purpose of the Lutheran Synod Quarterly, as was the purpose of the Clergy Bulletin, is to provide a testimony of the theological position of the Evangelical Lutheran Synod and also to promote the academic growth of her clergy roster by providing scholarly articles, rooted in the inerrancy of the Holy Scriptures and the Confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. The Lutheran Synod Quarterly is published in March and December with a combined June and September issue. Subscription rates are $25.00 U.S. per year for domestic subscriptions and $30.00 U.S. per year for international subscriptions. All subscriptions and editorial correspondence should be sent to the following address: Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary Attn: Lutheran Synod Quarterly 6 Browns Ct Mankato MN 56001 Back issues of the Lutheran Synod Quarterly from the past two years are available at a cost of $8.00 per issue. -

Church History

Village Missions Website: http://www.vmcdi.com Contenders Discipleship Initiative E-mail: [email protected] Church History Ecclesiology Church History History of Christian Doctrine Church History - Ecclesiology and the History of Christian Doctrine Contenders Discipleship Initiative – Church History Instructor’s Guide TRAINING MODULE SUMMARY Course Name Church History Course Number in Series 5 Creation Date August 2017 Created By: Russell Richardson Last Date Modified January 2018 Version Number 2 Copyright Note Contenders Bible School is a two-year ministry equipping program started in 1995 by Pastor Ron Sallee at Machias Community Church, Snohomish, WA. More information regarding the full Contenders program and copies of this guide and corresponding videos can be found at http://www.vmcontenders.org or http://www.vmcdi.com Copyright is retained by Village Missions with all rights reserved to protect the integrity of this material and the Village Missions Contenders Discipleship Initiative. Contenders Discipleship Initiative Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in the Contenders Discipleship Initiative courses are those of the instructors and authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of Village Missions. The viewpoints of Village Missions may be found at https://villagemissions.org/doctrinal-statement/ The Contenders program is provided free of charge and it is expected that those who receive freely will in turn give freely. Permission for non-commercial use is hereby granted but re-sale is prohibited. Copyright -

Protestant Scholasticism: Essays in Reassessment

PROTESTANT SCHOLASTICISM: ESSAYS IN REASSESSMENT Edited by Carl R. Trueman and R. Scott Clark paternoster press GRACE COLLEGE & THEO. SEM. Winona lake, Indiana Copyright© 1999 Carl R. Trueman and R. Scott Clark First published in 1999 by Paternoster Press 05 04 03 02 01 00 99 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paternoster Press is an imprint of Paternoster Publishing, P.O. Box 300, Carlisle, Cumbria, CA3 OQS, U.K. http://www.paternoster-publishing.com The rights of Carl R. Trueman and R. Scott Clark to be identified as the Editors of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1998. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying. In the U.K. such licences are issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London WlP 9HE. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-85364-853-0 Unless otherwise stated, Scripture quotations are taken from the / HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION Copyright© 1973, 1978, 1984 by the International Bible Society. Used by permission of Hodder and Stoughton Limited. All rights reserved. 'NIV' is a registered trademark of the International Bible Society UK trademark number 1448790 Cover Design by Mainstream, Lancaster Typeset by WestKey Ltd, Falmouth, Cornwall Printed in Great Britain by Caledonian International Book Manufacturing Ltd, Glasgow 2 Johann Gerhard's Doctrine of the Sacraments' David P. -

Vol. 25, No. 4 (December 1985)

FOREWORD In this issue of the Quarterly, we are pleased to bring you the 1985 Reformation lectures which were delivered at Bethany Lutheran College on LUTHERAN SYNOD QUARTERLY October 30-31, 1985. These annual lectures are sponsored jointly by Bethany College and Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary. The lectures this year were given in memory of Martin Chemnitz, Theological Journal of the whose theological leadership after ~uther'sdeath Evangelical Lutheran Synod no doubt saved the Reformation. Edited by the Faculty of The guest lecturers were Dr. Eugene Klug, Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary Mankato, Minnesota Professor of Systematic Theology at Concordia Theological Seminary, Fort Wayne, Indiana, and Dr. Jacob Preus, past president of the Lutheran Church--Missouri Synod. The reactor was Professor Arnold Koelpin, instructor of religion and history at Doctor Martin Luther College, New Ulm, Minne- sota. Dr. Klug lectured on Chemnitz -and Authority. He is also the author of several articles and essays and is best known for his book From Luther -to Chemnitz on Scripture ---and the Word. Dr. Preus is rememberedfor his valuable contribution in translating Chemnitz' Duabis Naturis --and De Editor: Pres. Wilhelm W. Petersen Coena Domini into English. He is currently work- Managing Editor: W. W. Petersen ing on sections of his Loci Theologici. Dr. reu us' Book Review Editor: J. B. Madson lecture was on Chemnitz -and Justification. The lectures are preceded by a biographical sketch Subscription Price: $5.00 per year of the life of Martin Chemnitz by the editor. Address all subscriptions and all correspondence Also included in this issue is a sermon LUTHERAN SYNOD QUARTERLY delivered by the editor at the 1985 fall General Bethany Lutheran ~heologicalSeminary Pastoral Conference communion service. -

Brief Historical Explanation of the Revelation of St. John, Acording To

BRIEF HISTORICAL EXPLANATION REVELATION OF ST JOHN, ACCORDING TO THE "HOM: APOCALYPTICvE" of the KEY. E. B. ELLIOTT, M.A. By H. CARRE TUCKER, C.B., late Bengal Civil Service. LONDON: JAMES NISBET & CO., 21 BERNERS STREET. M.dCCC.LXIII. BRIEF HISTORICAL EXPLANATION KEVELATION OF ST JOHN. EDINBURGH : PRINTED BY BALLANTYNE AND COMPANY, PAUL'S WORK. PKEFACE. The following Abridgment of Mr Elliott's work was planned when I was Governor-General's Agent and Commissioner of Benares, as one of a series of books published in India for the use of schools and native Christians, both in English and the vernaculars. It appeared to me that it was impossible for natives to peruse with understanding this important portion of God's Word, upon the reading, hearing, and keeping of which so special a blessing is promised, (Kev. i. 3, xxii. 7,) without some such brief and cheap epitome of the corresponding history, according to the best expositors. Assisted by Archdeacon Pratt's Para phrase, I have endeavoured just to take the cream of Mr Elliott's interpretation, so as to shew the mar vellous agreement between the prophecy and a suc cession of historical events, from the time when the vision took place, (Rev. i 19,) down to the present era. The knowledge of these true historical events, , VI PREFACE. and the remarks founded thereupon, will remain use ful, even should they not be those which the inspired penman had specially in view, and the commentator be consequently mistaken in his application of them to the prophecy. The Abridgment, interrupted by the Mutiny, is now completed and printed in English, in the hope that it may prove useful to some who cannot afford a more expensive explanation ; and also with a view to the preparation of counterparts in Hindustanee, Bengalee, Tamil, and other Indian languages, as God may enable me. -

On the Life and Faith of Florence Nightingale by Lynn Mcdonald, CM, Phd, LLD (Hon.), Professor Emerita

Reflection presented by Rev. Faye Greer 2020-05-17 On the Life and Faith of Florence Nightingale by Lynn McDonald, CM, PhD, LLD (Hon.), professor emerita (Note: The following reflection is offered for use in churches for the celebration of the bicentenary of Florence Nightingale’s birth, which was in 1820. Observances are taking place throughout 2020 to commemorate her.) Florence Nightingale was the founder of modern nursing. Despite family pressures to marry and live as a conventional wealthy woman, she considered her dedication to nursing to be a response to God’s call to care for the sick. Her success in radically lowering the death rate of wounded soldiers during the Crimean War (1853–1856) led to society’s acceptance of her proposals for better sanitation and nutrition, accurate medical knowledge, and professionally trained nurses. Selected Life Events Year Event 1820 born in Florence, Italy, to a wealthy British family (May 12) 1837, 1850 felt called by God to dedicate her life to nursing as a single woman 1850 visited Pastor Theodor Fliedner’s Lutheran deaconess community 1854–1855 worked as superintendent of a women’s hospital 1860 organized a nurses’ training school in London, England 1910 died in London (August 13) Florence Nightingale was baptized in the Church of England in the city of her birth, Florence, Italy. Three of her grandparents were Unitarians, but the one grandparent she knew was fiercely evangelical Church of England. Nightingale never identified as a Unitarian but remained in the Church of England, much as she disagreed with its social and theological conservatism. -

The Wesleyan Enlightenment

The Wesleyan Enlightenment: Closing the gap between heart religion and reason in Eighteenth Century England by Timothy Wayne Holgerson B.M.E., Oral Roberts University, 1984 M.M.E., Wichita State University, 1986 M.A., Asbury Theological Seminary, 1999 M.A., Kansas State University, 2011 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2017 Abstract John Wesley (1703-1791) was an Anglican priest who became the leader of Wesleyan Methodism, a renewal movement within the Church of England that began in the late 1730s. Although Wesley was not isolated from his enlightened age, historians of the Enlightenment and theologians of John Wesley have only recently begun to consider Wesley in the historical context of the Enlightenment. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to provide a comprehensive understanding of the complex relationship between a man, John Wesley, and an intellectual movement, the Enlightenment. As a comparative history, this study will analyze the juxtaposition of two historiographies, Wesley studies and Enlightenment studies. Surprisingly, Wesley scholars did not study John Wesley as an important theologian until the mid-1960s. Moreover, because social historians in the 1970s began to explore the unique ways people experienced the Enlightenment in different local, regional and national contexts, the plausibility of an English Enlightenment emerged for the first time in the early 1980s. As a result, in the late 1980s, scholars began to integrate the study of John Wesley and the Enlightenment. In other words, historians and theologians began to consider Wesley as a serious thinker in the context of an English Enlightenment that was not hostile to Christianity. -

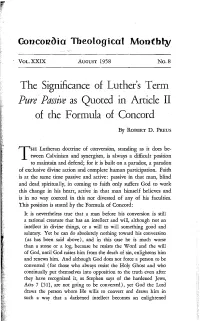

The Significance of Luther's Term Pure -Passive As Quoted in Article II of the Formula of Concord

GoncoJloia Theological Monthly , VOL.XXIX AUGUST 1958 No.8 The Significance of Luther's Term Pure -Passive as Quoted in Article II of the Formula of Concord By ROBERT D. Proms HE Lutheran doctrine of conversion, standing as it does be Ttween Calvinism and synergism, is always a difficult position to maintain and defend; for it is built on a paradox, a paradox of exclusive divine action and complete human participation. Faith is at the same time passive and active: passive in that man, blind and dead spiritually, in coming to faith only suffers God to work this change in his heart, active in that man himself believes and is in no way coerced in this nor divested of any of his faculties. This position is stated by the Formula of Concord: It is nevertheless true that a man before his conversion is still a rational creature that has an intellect and will, although not an intellect in divine things, or a will to will something good and salutary. Yet he can do absolutely nothing toward his conversion (as has been said above), and in this case he is much worse than a stone or a log, because he resists the Word and the will of God, until God raises him from the death of sin, enlightens him and renews him. And although God does not force a person to be converted (for those who always resist the Holy Ghost and who continually put themselves into opposition to the truth even after they have recognized it, as Stephen says of the hardened Jews, Acts 7 (51J, are not going to be converted), yet God the Lord draws the person whom He wills to convert and draws him in such a way that a darkened intellect becomes an enlightened 562 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF LUTHER'S TERM PURE PASSIVE intellect, and a perverse will becomes an obedient will. -

The Second Sunday of Advent

The Second Sunday of Advent THE HOLY EUCHARIST December 6, 2020, 11:00 AM The Church of Saint Mary the Virgin in the City of New York We Need Your Help We are enormously grateful to all the members and friends of Saint Mary’s from far and wide who have supported the parish during the extraordinary events of the past several months. Your gifts have encouraged us and they have kept us going. We hope that you will make a pledge to the parish for 2021 at this time. Pledge cards may be found on the ushers’ table at the Forty-sixth Street entrance to the church. If you are able to make an additional donation to support the parish at this time, we would happily receive it. Donations may be made online via the Giving section of the parish website. You may also make arrangements for other forms of payment by contacting our parish administrator, Christopher Howatt, who would be happy to assist you. He may be reached at 212-869-5830 x 10. If you have questions about pledging, please speak to a member of the clergy or to one of the members of the Stewardship Committee, MaryJane Boland, Steven Heffner, or Marie Rosseels. We are grateful to you for your support of Saint Mary’s. About the Music Today’s organ voluntaries are both from the North German Baroque school and are based upon Luther’s chorale Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland (“Come now, Savior of the Gentiles”). This chorale (54 in The Hymnal 1982) is Martin Luther’s sixteenth-century adaptation of the fourth-century Latin hymn Veni Redemptor gentium attributed to Ambrose of Milan (55 in The Hymnal 1982). -

Chamber Choir

CHAMBER CHOIR EUGENE ROGERS, DIRECTOR GRADUATE STUDENT CONDUCTORS SCOTT VANORNUM, ORGAN Sunday, April 25, 2021 Hill Auditorium 4:00 PM THREE BACH CANTATAS Aus der Tiefen rufe ich zu dir, BWV 131 Johann Sebastian Bach Aus der Tiefen rufe ich zu dir (1685–1750) So du willt, Herr Jacob Surzyn, bass Margaret Burk, conductor Ich harre des Herrn Meine Seele wartet Tyrese Byrd, tenor David Hahn, conductor Israel hoffe auf dem Herrn Julian Goods, conductor Nach dir, Herr, verlanget mich, BWV 150 Johann Sebastian Bach Sinfonia Nach dir, Herr, verlanget mich Doch bin und bleibe ich vergnügt Maia Aramburú, soprano Katherine Rohwer, conductor Leite mich in deiner Wahrheit Zedern müssen von den Winden Eliana Barwinski, alto; Jacob Carroll, tenor; Jacob Surzyn, bass Bryan Anthony Ijames, conductor Meine Augen sehen stets Meine Tage in dem Leide Maia Aramburu, soprano; Eliana Barwinski, mezzo-soprano Jacob Carroll, tenor; Julian Goods, bass Benjamin Gaughran, conductor THe use of all cameras and recording devices is strictly prohibited. Please turn off all cell phones and pagers or set ringers to silent mode. Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 61 Johann Sebastian Bach Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland Der Heiland ist gekommen Tyrese Byrd, tenor Komm, Jesu, komm zu deiner Kirche Jacob Carroll, tenor Siehe, ich stehe vor der Tür Jacob Surzyn, bass Öffne dich, mein ganzes Herze Cecilia Kowara, soprano Amen, Amen, komm du schöne Freudenkrone Joseph Kemper, conductor BACH, AUS DER TIEFEN RUFE ICH ZU DIR, BWV 131 In July 1707, 22-year-old Johann Sebastian Bach began his short tenure as organist of the Bla- siuskirche in Mühlhausen, one of two major churches in the free imperial city. -

Lutheran Spirituality and the Pastor

Lutheran Spirituality and the Pastor By Gaylin R. Schmeling I. The Devotional Writers and Lutheran Spirituality 2 A. History of Lutheran Spirituality 2 B. Baptism, the Foundation of Lutheran Spirituality 5 C. Mysticism and Mystical Union 9 D. Devotional Themes 11 E. Theology of the Cross 16 F. Comfort (Trost) of the Lord 17 II. The Aptitude of a Seelsorger and Spiritual Formation 19 A. Oratio: Prayer and Spiritual Formation 20 B. Meditatio: Meditation and Spiritual Formation 21 C. Tentatio: Affliction and Spiritual Formation 21 III. Proper Lutheran Meditation 22 A. Presuppositions of Meditation 22 B. False Views of Meditation 23 C. Outline of Lutheran Meditation 24 IV. Meditation on the Psalms 25 V. Conclusion 27 G.R. Schmeling Lutheran Spirituality 2 And the Pastor Lutheran Spirituality and the Pastor I. The Devotional Writers and Lutheran Spirituality The heart of Lutheran spirituality is found in Luther’s famous axiom Oratio, Meditatio, Tentatio (prayer, meditation, and affliction). The one who has been declared righteous through faith in Christ the crucified and who has died and rose in Baptism will, as the psalmist says, “delight … in the Law of the Lord and in His Law he meditates day and night” (Psalm 1:2). He will read, mark, learn, and take the Word to heart. Luther writes concerning meditation on the Biblical truths in the preface of the Large Catechism, “In such reading, conversation, and meditation the Holy Spirit is present and bestows ever new and greater light and devotion, so that it tastes better and better and is digested, as Christ also promises in Matthew 18[:20].”1 Through the Word and Sacraments the entire Trinity makes its dwelling in us and we have union and communion with the divine and are conformed to the image of Christ (Romans 8:29; Colossians 3:10). -

The Two Folk Churches in Finland

The Two Folk Churches in Finland The 12th Finnish Lutheran-Orthodox Theological Discussions 2014 Publications of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland 29 The Church and Action The Two Folk Churches in Finland The 12th Finnish Lutheran-Orthodox Theological Discussions 2014 Publications of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland 29 The Church and Action National Church Council Department for International Relations Helsinki 2015 The Two Folk Churches in Finland The 12th Finnish Lutheran-Orthodox Theological Discussions 2014 © National Church Council Department for International Relations Publications of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland 29 The Church and Action Documents exchanged between the churches (consultations and reports) Tasknumber: 2015-00362 Editor: Tomi Karttunen Translator: Rupert Moreton Book design: Unigrafia/ Hanna Sario Layout: Emma Martikainen Photos: Kirkon kuvapankki/Arto Takala, Heikki Jääskeläinen, Emma Martikainen ISBN 978-951-789-506-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-789-507-1 (PDF) ISSN 2341-9393 (Print) ISSN 2341-9407 (Online) Unigrafia Helsinki 2015 CONTENTS Foreword ..................................................................................................... 5 THE TWELFTH THEOLOGICAL DISCUSSIONS BETWEEN THE EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN CHURCH OF FINLAND AND THE ORTHODOX CHURCH OF FINLAND, 2014 Communiqué. ............................................................................................. 9 A Theological and Practical Overview of the Folk Church, opening speech Bishop Arseni ............................................................................................