Selecting Coastal Plain Species for Wind Resistance1 Mary L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

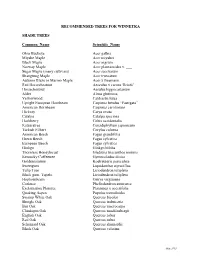

Recommended Trees for Winnetka

RECOMMENDED TREES FOR WINNETKA SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Ohio Buckeye Acer galbra Miyabe Maple Acer miyabei Black Maple Acer nigrum Norway Maple Acer plantanoides v. ___ Sugar Maple (many cultivars) Acer saccharum Shangtung Maple Acer truncatum Autumn Blaze or Marmo Maple Acer x freemanii Red Horsechestnut Aesculus x carnea 'Briotii' Horsechestnut Aesulus hippocastanum Alder Alnus glutinosa Yellowwood Caldrastis lutea Upright European Hornbeam Carpinus betulus “Fastigata” American Hornbeam Carpinus carolinians Hickory Carya ovata Catalpa Catalpa speciosa Hackberry Celtis occidentalis Katsuratree Cercidiphyllum japonicum Turkish Filbert Corylus colurna American Beech Fagus grandifolia Green Beech Fagus sylvatica European Beech Fagus sylvatica Ginkgo Ginkgo biloba Thornless Honeylocust Gleditsia triacanthos inermis Kentucky Coffeetree Gymnocladus dioica Goldenraintree Koelreuteria paniculata Sweetgum Liquidambar styraciflua Tulip Tree Liriodendron tulipfera Black gum, Tupelo Liriodendron tulipfera Hophornbeam Ostrya virginiana Corktree Phellodendron amurense Exclamation Plantree Plantanus x aceerifolia Quaking Aspen Populus tremuloides Swamp White Oak Quercus bicolor Shingle Oak Quercus imbricaria Bur Oak Quercus macrocarpa Chinkapin Oak Quercus muehlenbergii English Oak Quercus robur Red Oak Quercus rubra Schumard Oak Quercus shumardii Black Oak Quercus velutina May 2015 SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Sassafras Sassafras albidum American Linden Tilia Americana Littleleaf Linden (many cultivars) Tilia cordata Silver -

Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity of the Leaves, Bark and Stems of Liquidambar Styraciflua L

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2016) 5(1): 306-317 ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 5 Number 1(2016) pp. 306-317 Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article http://dx.doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2016.501.029 Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity of the Leaves, Bark and Stems of Liquidambar styraciflua L. (Altingiaceae) Graziele Francine Franco Mancarz1*, Ana Carolina Pareja Lobo1, Mariah Brandalise Baril1, Francisco de Assis Franco2 and Tomoe Nakashima1 1Pharmaceutical ScienceDepartment, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brazil 2Coodetec Desenvolvimento, Produção e Comercialização Agrícola Ltda, Cascavel, PR, Brazil *Corresponding author A B S T R A C T K e y w o r d s The genus Liquidambar L. is the best-known genus of the Altingiaceae Horan family, and species of this genus have long been used for the Liquidambar treatment of various diseases. Liquidambar styraciflua L., which is styraciflua, popularly known as sweet gum or alligator tree, is an aromatic deciduous antioxidant tree with leaves with 5-7 acute lobes and branched stems. In the present activity, study, we investigated the antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of aerial antimicrobial parts of L.styraciflua. Antimicrobial activity was evaluated using the activity, microdilution methodology. The DPPH and phosphomolybdenum methods microdilution method, were used to assess the antioxidant capacity of the samples. The extracts DPPH assay showed moderate or weak antimicrobial activity. The essential oil had the lowest MIC values and exhibited bactericidal action against Escherichia Article Info coli, Enterobacter aerogenes and Staphylococcus aureus. The ethyl acetate fraction and the butanol fraction from the bark and stem showed the best Accepted: antioxidant activity. -

Indiana's Native Magnolias

FNR-238 Purdue University Forestry and Natural Resources Know your Trees Series Indiana’s Native Magnolias Sally S. Weeks, Dendrologist Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 This publication is available in color at http://www.ces.purdue.edu/extmedia/fnr.htm Introduction When most Midwesterners think of a magnolia, images of the grand, evergreen southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) (Figure 1) usually come to mind. Even those familiar with magnolias tend to think of them as occurring only in the South, where a more moderate climate prevails. Seven species do indeed thrive, especially in the southern Appalachian Mountains. But how many Hoosiers know that there are two native species Figure 2. Cucumber magnolia when planted will grow well throughout Indiana. In Charles Deam’s Trees of Indiana, the author reports “it doubtless occurred in all or nearly all of the counties in southern Indiana south of a line drawn from Franklin to Knox counties.” It was mainly found as a scattered, woodland tree and considered very local. Today, it is known to occur in only three small native populations and is listed as State Endangered Figure 1. Southern magnolia by the Division of Nature Preserves within Indiana’s Department of Natural Resources. found in Indiana? Very few, I suspect. No native As the common name suggests, the immature magnolias occur further west than eastern Texas, fruits are green and resemble a cucumber so we “easterners” are uniquely blessed with the (Figure 3). Pioneers added the seeds to whisky presence of these beautiful flowering trees. to make bitters, a supposed remedy for many Indiana’s most “abundant” species, cucumber ailments. -

Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Honors Theses Honors College Spring 5-2016 Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi Hanna M. Miller University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Hanna M., "Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi" (2016). Honors Theses. 389. https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses/389 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi Vascular Flora of the Possum Walk Trail at the Infinity Science Center, Hancock County, Mississippi by Hanna Miller A Thesis Submitted to the Honors College of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in the Department of Biological Sciences May 2016 ii Approved by _________________________________ Mac H. Alford, Ph.D., Thesis Adviser Professor of Biological Sciences _________________________________ Shiao Y. Wang, Ph.D., Chair Department of Biological Sciences _________________________________ Ellen Weinauer, Ph.D., Dean Honors College iii Abstract The North American Coastal Plain contains some of the highest plant diversity in the temperate world. However, most of the region has remained unstudied, resulting in a lack of knowledge about the unique plant communities present there. -

United States Department of Agriculture

Pest Management Science Pest Manag Sci 59:788–800 (online: 2003) DOI: 10.1002/ps.721 United States Department of Agriculture—Agriculture Research Service research on targeted management of the Formosan subterranean termite Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae)†‡ Alan R Lax∗ and Weste LA Osbrink USDA-ARS-Southern Regional Research Center, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA Abstract: The Formosan subterranean termite, Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki is currently one of the most destructive pests in the USA. It is estimated to cost consumers over US $1 billion annually for preventative and remedial treatment and to repair damage caused by this insect. The mission of the Formosan Subterranean Termite Research Unit of the Agricultural Research Service is to demonstrate the most effective existing termite management technologies, integrate them into effective management systems, and provide fundamental problem-solving research for long-term, safe, effective and environmentally friendly new technologies. This article describes the epidemiology of the pest and highlights the research accomplished by the Agricultural Research Service on area-wide management of the termite and fundamental research on its biology that might provide the basis for future management technologies. Fundamental areas that are receiving attention are termite detection, termite colony development, nutrition and foraging, and the search for biological control agents. Other fertile areas include understanding termite symbionts that may provide an additional target for control. Area-wide management of the termite by using population suppression rather than protection of individual structures has been successful; however, much remains to be done to provide long-term sustainable population control. An educational component of the program has provided reliable information to homeowners and pest-control operators that should help slow the spread of this organism and allow rapid intervention in those areas which it infests. -

G-6 1 Maintenance and Planting of Parkway Trees

G-6 MAINTENANCE AND PLANTING OF PARKWAY TREES The City Council is vitally interested in beautification of City parkways. Public cooperation in helping to develop and maintain healthy and attractive parkway trees is encouraged. I. MAINTENANCE OF PARKWAY TREES The Municipal Operations Department will trim the parkway trees on a rotation schedule. An effort will be made to trim the parkway trees on less than a three- year cycle. If the rotation trimming is completed in less than three years, more frequent trimming will be performed on certain trees and in view areas. Public safety issues such as low branches and heavy foliage will be given priority over view trimming. An effort will be made to trim parkway trees located in heavy summer traffic areas during the fall and winter months. Annual trimming of certain species of trees prone to wind damage will be done prior to the winter season. II. TREE DESIGNATION LISTS The City Council has adopted an official street tree list, the Street Tree Designation List, which will be used by the Municipal Operations Department to determine species for replacement of trees removed from established parkways and for planning purposes in all new subdivisions and commercial developments. A second list, the Parkway Tree Designation List, has been added as a species palette for residents to choose approved, new and replacement, trees based on the size of parkway available for planting. The Municipal Operations Director will have the authority to add species to the Street and Parkway Tree Designation Lists, which will be updated on an annual basis by the Municipal Operations Department staff and reviewed by the Parks, Beaches and Recreation Commission (“Commission”) for approval before adoption by the City Council. -

Tree of the Year: Liquidambar Eric Hsu and Susyn Andrews

Tree of the Year: Liquidambar Eric Hsu and Susyn Andrews With contributions from Anne Boscawen (UK), John Bulmer (UK), Koen Camelbeke (Belgium), John Gammon (UK), Hugh Glen (South Africa), Philippe de Spoelberch (Belgium), Dick van Hoey Smith (The Netherlands), Robert Vernon (UK) and Ulrich Würth (Germany). Affinities, generic distribution and fossil record Liquidambar L. has close taxonomic affinities with Altingia Noronha since these two genera share gum ducts associated with vascular bundles, terminal buds enclosed within numerous bud scales, spirally arranged stipulate leaves, poly- porate (with several pore-like apertures) pollen grains, condensed bisexual inflorescences, perfect or imperfect flowers, and winged seeds. Not surpris- ingly, Liquidambar, Altingia and Semiliquidambar H.T. Chang have now been placed in the Altingiaceae, as originally treated (Blume 1828, Wilson 1905, Chang 1964, Melikan 1973, Li et al. 1988, Zhou & Jiang 1990, Wang 1992, Qui et al. 1998, APG 1998, Judd et al. 1999, Shi et al. 2001 and V. Savolainen pers. comm.). These three genera were placed in the subfamily Altingioideae in Hamamelidaceae (Reinsch 1890, Chang 1979, Cronquist 1981, Bogle 1986, Endress 1989) or the Liquidambaroideae (Harms 1930). Shi et al. (2001) noted that Altingia species are evergreen with entire, unlobed leaves; Liquidambar is deciduous with 3-5 or 7-lobed leaves; while Semiliquidambar is evergreen or deciduous, with trilobed, simple or one-lobed leaves. Cytological studies have indicated that the chromosome number of Liquidambar is 2n = 30, 32 (Anderson & Sax 1935, Pizzolongo 1958, Santamour 1972, Goldblatt & Endress 1977). Ferguson (1989) stated that this chromosome number distinguished Liquidambar from the rest of the Hamamelidaceae with their chromosome numbers of 2n = 16, 24, 36, 48, 64 and 72. -

Liquidambar Styraciflua L.) from Caroline County, Virginia

43 Banisteria, Number 9, 1997 © 1997 by the Virginia Natural History Society An Abnormal Variant of Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua L.) from Caroline County, Virginia Bruce L. King Department of Biology Randolph Macon College Ashland, Virginia 23005 Leaves of individuals of Liquidambar styraciflua L. Similar measurements were made from surrounding (sweetgum) - are predominantly 5-lobed, occasionally 7- plants in three height classes:, early sapling, 61-134 cm; lobed or 3-lobed (Radford et al., 1968; Cocke, 1974; large seedlings, 10-23 cm; and small seedlings (mostly first Grimm, 1983; Duncan & Duncan, 1988). The tips of the year), 3-8.5 cm. All of the small seedlings were within 5 lobes are acute and leaf margins are serrate, rarely entire. meters of the atypical specimen and most of the large In 1991, I found a seedling (2-3 yr old) that I seedlings and saplings were within 10 meters. The greatest tentatively identified as a specimen of Liquidambar styrac- distance between any two plants was 70 meters. All of the iflua. The specimen occurs in a 20 acre section of plants measured were in dense to moderate shade. In the deciduous forest located between U.S. Route 1 and seedling classes, three leaves were measured from each of Waverly Drive, 3.2 km south of Ladysmith, Caroline ten plants (n = 30 leaves). In the sapling class, counts of County, Virginia. The seedling was found at the middle leaf lobes and observations of lobe tips and leaf margins of a 10% slope. Dominant trees on the upper slope were made from ten leaves from each of 20 plants (n include Quercus alba L., Q. -

Approved Plants For

Perennials, Ground Covers, Annuals & Bulbs Scientific name Common name Achillea millefolium Common Yarrow Alchemilla mollis Lady's Mantle Aster novae-angliae New England Aster Astilbe spp. Astilbe Carex glauca Blue Sedge Carex grayi Morningstar Sedge Carex stricta Tussock Sedge Ceratostigma plumbaginoides Leadwort/Plumbago Chelone glabra White Turtlehead Chrysanthemum spp. Chrysanthemum Convallaria majalis Lily-of-the-Valley Coreopsis lanceolata Lanceleaf Tickseed Coreopsis rosea Rosy Coreopsis Coreopsis tinctoria Golden Tickseed Coreopsis verticillata Threadleaf Coreopsis Dryopteris erythrosora Autumn Fern Dryopteris marginalis Leatherleaf Wood Fern Echinacea purpurea 'Magnus' Magnus Coneflower Epigaea repens Trailing Arbutus Eupatorium coelestinum Hardy Ageratum Eupatorium hyssopifolium Hyssopleaf Thoroughwort Eupatorium maculatum Joe-Pye Weed Eupatorium perfoliatum Boneset Eupatorium purpureum Sweet Joe-Pye Weed Geranium maculatum Wild Geranium Hedera helix English Ivy Hemerocallis spp. Daylily Hibiscus moscheutos Rose Mallow Hosta spp. Plantain Lily Hydrangea quercifolia Oakleaf Hydrangea Iris sibirica Siberian Iris Iris versicolor Blue Flag Iris Lantana camara Yellow Sage Liatris spicata Gay-feather Liriope muscari Blue Lily-turf Liriope variegata Variegated Liriope Lobelia cardinalis Cardinal Flower Lobelia siphilitica Blue Cardinal Flower Lonicera sempervirens Coral Honeysuckle Narcissus spp. Daffodil Nepeta x faassenii Catmint Onoclea sensibilis Sensitive Fern Osmunda cinnamomea Cinnamon Fern Pelargonium x domesticum Martha Washington -

Wood from Midwestern Trees Purdue EXTENSION

PURDUE EXTENSION FNR-270 Daniel L. Cassens Professor, Wood Products Eva Haviarova Assistant Professor, Wood Science Sally Weeks Dendrology Laboratory Manager Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University Indiana and the Midwestern land, but the remaining areas soon states are home to a diverse array reforested themselves with young of tree species. In total there are stands of trees, many of which have approximately 100 native tree been harvested and replaced by yet species and 150 shrub species. another generation of trees. This Indiana is a long state, and because continuous process testifies to the of that, species composition changes renewability of the wood resource significantly from north to south. and the ecosystem associated with it. A number of species such as bald Today, the wood manufacturing cypress (Taxodium distichum), cherry sector ranks first among all bark, and overcup oak (Quercus agricultural commodities in terms pagoda and Q. lyrata) respectively are of economic impact. Indiana forests native only to the Ohio Valley region provide jobs to nearly 50,000 and areas further south; whereas, individuals and add about $2.75 northern Indiana has several species billion dollars to the state’s economy. such as tamarack (Larix laricina), There are not as many lumber quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), categories as there are species of and jack pine (Pinus banksiana) that trees. Once trees from the same are more commonly associated with genus, or taxon, such as ash, white the upper Great Lake states. oak, or red oak are processed into In urban environments, native lumber, there is no way to separate species provide shade and diversity the woods of individual species. -

Water's Park Tree Inventory and Assessment

Arborist’s Report Tree Inventory and Assessment 1 Waters Park Drive San Mateo, CA 94403 Prepared for: Strada Investment Group March 3, 2018 Prepared By: Richard Gessner ASCA - Registered Consulting Arborist ® #496 ISA - Board Certified Master Arborist® WE-4341B ISA - Tree Risk Assessor Qualified CA Qualified Applicators License QL 104230 © Copyright Monarch Consulting Arborists LLC, 2018 1 Waters Park Drive, San Mateo Tree Inventory and Assessment March 3, 2018 Table of Contents Summary............................................................................................................... 1 Introduction........................................................................................................... 2 Background ............................................................................................................2 Assignment .............................................................................................................2 Limits of the assignment ........................................................................................2 Purpose and use of the report ................................................................................3 Observations......................................................................................................... 3 Tree Inventory .........................................................................................................3 Analysis................................................................................................................