Missions and the Liberation of Theology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AFRICANUS JOURNAL Vol

AFRICANUS JOURNAL Vol. 13 No. 1 | April 2021 africanus journal vol. 13, no. 1 April 2021 Contents 3 Goals of the Journal 3 Life of Africanus 3 Other Front Matter 5 Inaugural Acceptance Speech Fall 1969 Harold John Ockenga 9 Serving the Global Church as a World Christian Daewon Moon 13 Not by Might or Power but by My Spirit Ursula Williams 19 Boulders, Bridges, and Destiny and the Often-Obscure Connections William C. Hill 23 God's Masterpiece Wilma Faye Mathis 29 My Spiritual Journey of Maturing (or Growing) in God's Love and Faithfulness Leslie McKinney Attema 35 Navigating between Contexts and Texts for Ministry as Theological- Missional Calling while Appreciating the Wisdom of Retrievals for Renewal and Lessons Learned from My Early Seminary Days David A. Escobar Arcay 39 Review of Why Church? A Basic Introduction Jinsook Kim 41 Review of 1 Timothy and 2 Timothy and Titus Jennifer Creamer 44 Review of The Story of Creeds and Confessions: Tracing the Development of the Christian Faith William David Spencer 48 Review of Serve the People Jeanne DeFazio 1 50 Review of Three Pieces of Glass: Why We Feel Lonely in a World Mediated by Screens Dean Borgman 54 Review of Healing the Wounds of Sexual Abuse: Reading the Bible with Survivors Jean A. Dimock 57 Review of A Defense for the Chronological Order of Luke's Gospel Hojoon J. Ahn 2 Goals of the Africanus Journal The Africanus Journal is an award-winning interdisciplinary biblical, theological, and practical journal of the Center for Urban Ministerial Education (CUME). -

A Christology for Frontier Mission: a Missiological Study of Colossians by Brad Gill

Households in Focus A Christology for Frontier Mission: A Missiological Study of Colossians by Brad Gill Editor’s Note: This article was presented to the Asia Society for Frontier Mission, Bangkok, Thailand, October 2017. would like to reaffirm our strategic cooperation in frontier mission by examining a rather uncommon portion of scripture for missiological reflec- tion. Cooperation emerges from the objects we love, those purposes and goals we share, and I believe that in the epistle to the Colossians the Apostle Paul I 1 offers us a christological vision that grounds our mission in a common love. Colossians as a Missiological Statement Recently I was plowing through a new book by John Flett entitled Apostolicity: The Ecumenical Question in World Christian Perspective.2 The author explained how the growing pluriformity of world Christianity should reorient our understanding of the apostolic continuity of the church. I don’t usually read books on ecumenical unity, but this one had come in the mail (since I’m an editor) and something in the review had caught my eye: that the rationale for ecumenical unity over the past century had placed limits on cross-cultural engagement and the appropriation of the gospel. Those words have missio- logical implication. At one point towards the end of his book, in his chapter on Jesus Christ as the ground of our apostolic mission, he refers the reader to Colossians. If then you have been raised up with Christ, keep seeking the things above, where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God. Set your mind on the things above, not on the things that are on earth. -

Vol 57 No.3 DEC 2009 FILE.Indd

New Horizons in Education, Vol.57, No.3 (Special Issue), December 2009 Where we are now: a review of service-learning among SLAN Colleges and universities in Asia Florence E. McCarthy International Christian University Abstract Background: Service-learning in the Service-Learning Asian Network (SLAN), is organized as part of the academic structure of member institutions, and includes both international and community (domestic) service-learning. SLAN began with the exchange of students between SLAN institutions and has progressed to multicultural service-learning exchange programs and collaborative research. Aim: The intent of this article is to illustrate the development of Asian service-learning by reviewing the progress that has been made in six SLAN service-learning programs, illustrating differences and shared characteristics. These include: consistency in programs, multicultural exchange, and collaborative research. Lessons learned and main outcomes of the research are presented. Argument: Among lessons learned are the importance of multicultural programs to promote greater acceptance and understanding of socio-cultural differences by students; the importance of student preparation before service, and community agency orientation to enhance the reciprocities of exchange between students, agency staff, and local people. Student outcomes include personal growth, enhanced social skills, intercultural learning, and increased academic abilities. Conclusions: Progress has been made in institutionalizing service-learning among SLAN institutions. -

Cleansing the Cosmos

CLEANSING THE COSMOS: A BIBLICAL MODEL FOR CONCEPTUALIZING AND COUNTERACTING EVIL By E. Janet Warren A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham November 14, 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSRACT Understanding evil spiritual forces is essential for Christian theology. Evil has typically been studied either from a philosophical perspective or through the lens of ‘spiritual warfare’. The first seldom considers demonology; the second is flawed by poor methodology. Furthermore, warfare language is problematic, being very dualistic, associated with violence and poorly applicable to ministry. This study addresses these issues by developing a new model for conceptualizing and counteracting evil using ‘non-warfare’ biblical metaphors, and relying on contemporary metaphor theory, which claims that metaphors are cognitive and can depict reality. In developing this model, I examine four biblical themes with respect to alternate metaphors for evil: Creation, Cult, Christ and Church. Insights from anthropology (binary oppositions), theology (dualism, nothingness) and science (chaos-complexity theory) contribute to the construction of the model, and the concepts of profane space, sacred space and sacred actions (divine initiative and human responsibility) guide the investigation. -

Jews and Christians: Perspectives on Mission the Lambeth-Jewish Forum

Jews and Christians: Perspectives on Mission The Lambeth-Jewish Forum Reuven Silverman, Patrick Morrow and Daniel Langton Jews and Christians: Perspectives on Mission The Lambeth-Jewish Forum Both Christianity and Judaism have a vocation to mission. In the Book of the Prophet Isaiah, God’s people are spoken of as a light to the nations. Yet mission is one of the most sensitive and divisive areas in Jewish-Christian relations. For Christians, mission lies at the heart of their faith because they understand themselves as participating in the mission of God to the world. As the recent Anglican Communion document, Generous Love, puts it: “The boundless life and perfect love which abide forever in the heart of the Trinity are sent out into the world in a mission of renewal and restoration in which we are called to share. As members of the Church of the Triune God, we are to abide among our neighbours of different faiths as signs of God’s presence with them, and we are sent to engage with our neighbours as agents of God’s mission to them.”1 As part of the lifeblood of Christian discipleship, mission has been understood and worked out in a wide range of ways, including teaching, healing, evangelism, political involvement and social renewal. Within this broad and rich understanding of mission, one key aspect is the relation between mission and evangelism. In particular, given the focus of the Lambeth-Jewish Forum, how does the Christian understanding of mission affects relations between Christianity and Judaism? Christian mission and Judaism has been controversial both between Christians and Jews, and among Christians themselves. -

The “Gospel” of Cultural Sustainability: Missiological Insights

The “Gospel” of Cultural Sustainability: Missiological Insights Anna Ralph Master’s Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at Goucher College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Cultural Sustainability Goucher College—Towson, Maryland May 2013 Advisory Committee Amy Skillman, M.A. (Advisor) Rory Turner, PhD Richard Showalter, DMin Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... iii Chapter One—The Conceptual Groundwork ................................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 Definition—“Missiology” .................................................................................................... 4 Definition—“Cultural Sustainability” .................................................................................. 5 Rationale ............................................................................................................................. 7 Methodology ..................................................................................................................... 11 Review of Literature—Cultural Sustainability................................................................... 12 Review of Literature—Missiology .................................................................................... -

Hermeneutics, Culture, and the Father of the Faithful

Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 13/1 (Spring 2002): 91Ð114. Article copyright © 2002 by Lael Caesar. Hermeneutics, Culture, and the Father of the Faithful Lael Caesar Andrews University Biblical hermeneutics and human socialization are a significantly uncom- fortable pair. Indeed, it is only natural for culture and hermeneutics to be in con- stant contention, and yet they are forever in each otherÕs company. They seem to claim the same level of authority for determining human behavior, so that while the believer may hold that God and His Word are everything, that very believer, as anthropologist or sociologist, knows that culture is everything. This is be- cause, despite our faith in the Holy Scriptures as authoritative, infallible, and prescriptive of conduct, no one has ever experienced Scripture outside of a hu- man social context. Nor do we here propose how that might be accomplished. Neither do we explore that ample specialty known as cultural hermeneutics.1 Rather, this paper examines the relationship between sound biblical hermeneu- tics and societal norms of conduct in the hope of demonstrating how salvific outcomes are possible from the interaction of the two. It attempts to show how a valid interpretation of GodÕs Word may be accessed and effectively transmitted across cultures. Defining Culture When we speak of biblical hermeneutics, we refer to the science, such as it is, of interpretation of Scripture. But what do we mean when we speak of Òcul- tureÓ? What does the idea of culture embrace? One may retort with a somewhat different question: What does the idea not embrace? For culture 1 ÒThe study of peopleÕs beliefs about the meaning of life and about what it means to be hu- man.Ó Kevin J. -

MISSIONS Don L. Meredith Harding School of Theology 2016/17 R.R

1 MISSIONS Don L. Meredith Harding School of Theology 2016/17 R.R.016.266/P484. Petersen, Paul D., ed. Missions and Evangelism: A Bibliography Selected from the ATLA Religion Database. Rev. ed. Chicago, IL: ATLA, 1985. Subject index, with abstracts, of articles from ATLA Religion Database (1949-1984) and D.Min. theses from Research in Ministry (1981-84). Contains author & book review indexes. R.R.016.266/B582. Bibliographia Missionaria. Isola del Liri: Soc. Tip. A. Maloce & Pisani, 1933- . An annual classified bibliography of books and articles (primarily Catholic) on missions. Contains author/person and subject indexes. Vol. 1-49 (1933-85) published as Bibliografia Missionaria. R.R.016.266/I61. Thomas, Norman E., ed. International Mission Bibliography: 1960-2000. ATLA Bibliographies, 48. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2003. Contains 15,850 annotated entries for the most important missiological books published in English and a selection of those in each major European language from 1960 to 2000. Arranged under 20 sub-headings with a personal name index. To supplement this bibliography a "Selected Annotated Bibliography on Missiology" was published in installments (each including about 30 new titles) in each issue of Missiology (2000-July 2004) corresponding to the sub-headings in the published volume. *R.R.016.27/I61. International Christian Literature Documentation Project. 2v. Evanston, IL: ATLA, 1993. Indexes "printed materials (wherever published) that document Christian life and mission in the non- Western world." Indexes 18,635 monographs and pamphlets and 6,774 essays in 1,843 multi-author works. Vol. 1 is subject index and vol. 2 is author-editor and corporate name index. -

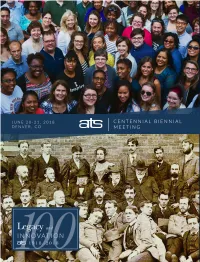

Biennial Program Book

Our mission To promote the improvement and enhancement of theological schools to the benefit of communities of faith and the broader public. Top cover photo—Copyright: Wesley Theological Seminary, 2017. Used with permission. Contents Hotel Floorplan iv Meeting Agenda 1 Workshops 4 Innovation Expo 7 Participants in the Program 12 Officers and Directors 14 Message from the Executive Director 16 ATS Distinguished Service Awards 17 Past ATS Presidents 18 Past Commission on Accrediting Chairs 19 Past Biennial Meeting Sites 20 ATS Milestones 21 Rules for the Conduct of Business 22 COMMISSION ON ACCREDITING BUSINESS Report of the Board of Commissioners 24 Motion and Process for Redevelopment of the Standards 32 Proposed Revisions to the Commission Bylaws 41 Report of the Commission Treasurer 44 Report of the Commission Nominating Committee 47 ASSOCIATION BUSINESS Report of the Association Board of Directors 50 Membership Report 55 Associate Membership Applicants 56 Affiliate Status Applicants 78 Plan for the Work of ATS: 2018–2024 80 Proposed Revisions to the Association Bylaws 85 Report of the Association Treasurer 88 Report of the Association Nominating Committee 92 REPORTS Committee on Race and Ethnicity 94 Economic Challenges Facing Future Ministers Project 96 Educational Models and Practices in Theological Education Project 98 Faculty Development Advisory Committee 102 Global Awareness and Engagement Initiative 104 Governance in Theological Schools Initiative 105 Leadership Education Program 106 Henry Luce III Fellows in Theology 108 Research and Data Advisory Committee 110 Science for Seminaries Projects 112 Student Data and Resources Advisory Committee 114 Theological Education Editorial Board 116 Women in Leadership Advisory Committee 117 Forum for Theological Exploration, Inc 119 iii Hotel Floorplan iv AGENDA Meeting Agenda TUESDAY, JUNE 19 9:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. -

Theories of Culture: a New Agenda for Theology, Ministry, and Faith Formation by Nate Frambach, Wartburg Seminary, Dubuque, IA

Theories of Culture: A New Agenda for Theology, Ministry, and Faith Formation By Nate Frambach, Wartburg Seminary, Dubuque, IA Workshop Description: Theories of Culture: A New Agenda for Theology, Ministry, and Faith Formation Culture: a familiar word that rolls off the tongue rather easily, perhaps casually, as though it needs no explication. How do we move beyond popular definitions to a deeper understanding of the notion of culture for today? Three assertions: • The Christian gospel and culture(s) cannot be separated; • We live within a pluriverse of cultures; • Congregations are one of those cultures. This workshop will help participants better understand the reality of culture(s) today for the sake of faithful, truthful, and effective ministry in a missional age. Beginning: Preface/Notes for the Leader: You know this, but creating a trustworthy and hospitable space to learn together is important so use your best practices to establish the learning environment. Throughout the script that follows I will provide you with occasional prompts (e.g., “Say…”). Although this might be a bit pedantic, the point is not to insult you, but rather to indicate what is teaching or presenting material for the audience as opposed to commentary for you as the leader. By all means, feel free to modify, edit, or otherwise make it your own. Getting Started: Obviously, you will want to introduce yourself, welcome the participants to the workshop setting, and remind people about the focus for the session (workshop topic/description). If you’re funny, tell a joke; if not, tell someone else’s joke. Depending on the size of the gathering/workshop, you may want to have participants introduce themselves to one another. -

Library Strategies for Meeting The

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Proceedings of the IATUL Conferences 2012 IATUL Proceedings Jun 5th, 12:00 AM Library Strategies for Meeting the Learning Needs of Fine Arts Students in the 21st Century: The Experience of New Asia College Ch'ien Mu Library of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Leo F.H. Ma Chinese University of Hong Kong, [email protected] Leo F.H. Ma, "Library Strategies for Meeting the Learning Needs of Fine Arts Students in the 21st Century: The Experience of New Asia College Ch'ien Mu Library of the Chinese University of Hong Kong." Proceedings of the IATUL Conferences. Paper 35. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/iatul/2012/papers/35 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. LIBRARY STRATEGIES FOR MEETING THE LEARNING NEEDS OF FINE ARTS STUDENTS IN THE 21ST CENTURY: THE EXPERIENCE OF NEW ASIA COLLEGE CH’IEN MU LIBRARY OF THE CHINESE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG LEO F.H. MA The Chinese University of Hong Kong; Hong Kong; [email protected] Abstract Being the only university to adopt a college system in Hong Kong, The Chinese University of Hong Kong has at present nine constituent colleges, one of which is New Asia College. Compared to the other colleges, New Asia College has strong emphasis on the arts and humanities in general and on the traditional Chinese culture in particular. The Ch’ien Mu Library of New Asia College houses an extensive collection of fine arts to support the academic curriculum of the Department of Fine Arts located in the same campus of the College. -

KP Aleaz, "Gospel and Culture: Some Indian Reflections,"

Gospel and Culture: Some Indian Reflections KP. ALEAZ* In this paper we present some of the findings of a commissioned study of the World Council of Churches on Gospel and Culture which we had the privilege to undertake. The Study is an elucidation of a double gospel emerging out of the Indian culture: on the one hand we have the. gospel of inter-religious interaction and the consequent composite culture of India and on the other, there is the gospel of God in Jesus arising out of the Indian hermeneutical context, which only mutually ratify one another. Culture denotes all the capabilities and habits acquired by human person as a member of a particular society, such as knowledge, belief, art, law, customs ek It is the whole way of life, material, intellectual and spiritual. It describes the way human beings think, feel, believe ·and behave. Culture is a comprehensive term and includes the following: (i) patterns and modes of external behaviour; (ii) the productive level of agriculture, industry, services and information, (iii) the social level of political economy or power ,. relations among human beings; and (iv) basic postures, values, beliefs, world views, which form the foundations of a culture and which find expression in art, music, literature, philosophy and religion. 1. The Research Problem . Historically, India has been one of the greatest confluences of different cultural strands. The composite culture of India is a product of borrowing, sharing and fusing through processes of interaction between two or more streams and such cultural symbiosis has given birth to greater vitality and larger acceptability.