CULTURAL ELEMENTS of the MANDRA SYSTEM of LEMNOS: a NARRATIVE APPROACH Terra Lemnia Project / Strategy 1.3 / Activity 1.3.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timetables from 01/11/15 to 31/12/15 Departures

SHIPPING AGENCY MILIADIS TEL. +30 2510 226147 – 223421 FAX. +30 2510 230231 TERMINAL STATION PORT KAVALA E-MAIL. [email protected] WEBSITE. www.miliadou.gr TIMETABLES FROM 01/11/15 TO 31/12/15 F/B NISSOS MYKONOS F/B – EXPRESS PEGASUS DEPARTURES AR. 12:30 TUESDAY LIMNOS - AG.EYSTRATIOS - LAVRIO «EXPRESS PEGASUS» DE. 16:00 AR.19:00 LIMNOS – MYTILENE-CHIOS-BATHI- WEDNESDAY KARLOVASI-FOYRNOI-AG.KIRIKOS- «NISSOS MYKONOS» DE. 21:30 MYKONOS-SYROS-PIRAEUS ΤHURSDAY AR.12:30 LIMNOS - AG.EYSTRATIOS - LAVRIO «EXPRESS PEGASUS» DE. 16:00 AR. 19:00 LIMNOS – MYTILENE-CHIOS-BATHI- SATURDAY KARLOVASI-FOYRNOI-EVDILOS- « NISSOS MYKONOS » DE. 21:30 MYKONOS-SYROS-PIRAEUS AR.SAT 05:15 SUNDAY LIMNOS - AG.EYSTRATIOS - LAVRIO «EXPRESS PEGASUS» DE. 16:00 TA ∆ΡΟΜΟΛΟΓΙΑ ΥΠΟΚΕΙΝΤΑΙ ΣΕ ΤΡΟΠΟΠΟΙΗΣΕΙΣ SHIPPING AGENCY MILIADIS TEL. +30 2510 226147 – 223421 FAX. +30 2510 230231 TERMINAL STATION PORT KAVALA E-MAIL. [email protected] WEBSITE. www.miliadou.gr RETURNS TUESDAY 08:00 «EXPRESS PEGASUS» WEDNESDAY 15:30 «NISSOS MYKONOS» FROM LIMNOS: THURSDAY 08:00 «EXPRESS PEGASUS» SATURDAY 00:45 «EXPRESS PEGASUS» SATURDAY 15:30 « NISSOS MYKONOS » TUESDAY 04:40 «EXPRESS PEGASUS» FROM AG.EYSTRATIOS: THURSDAY 04:40 «EXPRESS PEGASUS» FRIDAY 22:10 «EXPRESS PEGASUS» WEDNESDAY 10:45 « NISSOS MYKONOS » FROM MYTILENE: SATURDAY 10:45 « NISSOS MYKONOS » WEDNESDAY 07:00 « NISSOS MYKONOS » FROM CHIOS: SATURDAY 07:00 « NISSOS MYKONOS » WEDNESDAY 04:00 « NISSOS MYKONOS » FROM BATHI: SATURDAY 04:00 « NISSOS MYKONOS » WEDNESDAY 02:30 FROM KARLOVASI: « NISSOS MYKONOS » SATURDAY 02:30 WEDNESDAY 01:05 FROM FOYRNOI: « NISSOS MYKONOS » SATURDAY 01:05 FROM AG.KIRIKO: WEDNESDAY 00:20 « NISSOS MYKONOS » FROM EVDILO: FRIDAY 24:00 TUESDAY 21:30 FROM MYKONOS: « NISSOS MYKONOS » FRIDAY 21:20 TUESDAY 20:15 FROM SYROS: « NISSOS MYKONOS » FRIDAY 20:15 MONDAY 21:00 «EXPRESS PEGASUS» FROM LAYRIO: WEDNESDAY 21:00 «EXPRESS PEGASUS» FRIDAY 14:30 «EXPRESS PEGASUS» TA ∆ΡΟΜΟΛΟΓΙΑ ΥΠΟΚΕΙΝΤΑΙ ΣΕ ΤΡΟΠΟΠΟΙΗΣΕΙΣ SHIPPING AGENCY MILIADIS TEL. -

Winelist Fall 19.Pdf

u WINES BY THE GLASS u ποτήρι κρασί Retsina glass bottle 17 Kechris, ‘Tear of the Pine’ Retsina, Thessaloniki 14 56 18 Kechris, ‘Kechribari’ Retsina, Thessaloniki, 500ml 12 Sparkling 12 Glinavos ‘Zitsa Brut,’ Zitsa, Epirus 16 64 17 Kir-Yianni Rosé ‘Akakies,’ Amyndaio 13 52 Wh i t e 17 Moschofilero, Troupis ‘Fteri,’ Arkadia 11 44 18 Assyrtiko, Gai’a ‘Thalassitis,’ Santorini 16 64 17 Malvasia, Douloufakis ‘Femina,’ Crete 13 52 17 Assyrtiko / Malagouzia, Domaine Nerantzi 16 64 ‘Pentapolis,’ Serres, Macedonia Orange 18 Sauvignon Blanc, Oenogenisis ‘Mataroa,’ Drama 14 56 Rosé 17 Sideritis, Ktima Parparoussis ‘Petit Fleur,’ Achaia, Peloponnese 13 52 Red 17 Xinomavro, Thymiopoulos ‘Young Vines,’ Naoussa 13 52 17 Mavrodaphne, Sklavos ‘Orgion,’ Kefalonia 16 64 16 Agiorgitiko, Tselepos, Nemea, Peloponnese 13 52 16 Limniona, Domaine Zafeirakis, Tyrnavos, Thessaly 16 64 16 Tsapournakos, Voyatzi, Velvento, Macedonia 16 64 Carafe white/red καράφα Please ask your server! 32 u u u u u u WINES BY THE BOTtLE SPARKLING αφρώδες κρασί orange πορτοκαλί κρασί 17 Domaine Spiropoulos ‘Ode Panos’ Brut, Mantinia, Peloponnese 58 17 Roditis / Moschatela / Vostylidi / Muscat, Sclavos ‘Alchymiste,’ Kefalonia 38 Stone fruits and fl owers. Nectar of the gods. Dip your toes in the orange wine pool with this staff fave. Aromatic and affable. 13 Tselepos ‘Amalia’ Brut, Nemea, Peloponnese 90 18 Savatiano, Georgas Family, Spata 48 Rustic and earthy, from the hottest, driest region in Greece. Sort of miracle wine. Better than Veuve. (For real, though.) NV Tselepos ‘Amalia’ Brut Roze, Nemea, Peloponnese 60 NV Aspro Potamisi / Rosaki, Kathalas ‘Un Été Grec’, Tinos 120 The new cult classic. -

European Commission

EUROPEAN COMMISSION PRESS RELEASE Brussels, 23 April 2013 Mergers: Commission opens in-depth investigation into proposed acquisition of Olympic Air by Aegean Airlines The European Commission has opened an in-depth investigation under the EU Merger Regulation into the proposed acquisition of Olympic Air by Aegean Airlines. The companies are the two main Greek airlines offering passenger air transport services on Greek domestic and international routes. Each of the companies operates a base at Athens International Airport. The Commission has concerns that the transaction may lead to price increases and poorer service on several domestic Greek routes out of Athens, where the merged entity would have a monopoly or an otherwise strong market position. The opening of an in-depth inquiry does not prejudge the outcome of the investigation. The Commission now has 90 working days, until 3 September 2013, to take a decision on whether the proposed transaction would significantly impede effective competition in the European Economic Area (EEA). Commission Vice President in charge of competition policy Joaquín Almunia said: "We have the duty to ensure that Greek passengers and people visiting Greece can travel at competitive air fares, even more so during challenging economic times." The Commission’s initial market investigation indicated that the proposed transaction raises serious competition concerns on a number of Greek domestic routes where Aegean and Olympic currently compete or are well placed to compete. These routes are used not only by Greek passengers, but also by a large number of foreign travellers, given the popularity of Greece as a tourist destination. The Commission's assessment takes account of relevant factors, such as the state of the Greek economy and the financial situation of the parties. -

LIMNOS Letecké Zájezdy Na 7, 10, 11 Nocí

LIMNOS Letecké zájezdy na 7, 10, 11 nocí Odletové místo Praha Let na Limnos je s mezipřistáním v Kavale, let zpět je přímý. LIMNOS DOMOV ŘECKÉHO BOHA OHNĚ HÉFAISTA OSTROV TISÍCE POCITŮ Limnos je jedinečný, malebný a turismem V restauraci ochutnejte místní domácí těstoviny ještě neobjevený ostrov v severovýchodní (valanes, aftoudia, fiongakia, flomaria), DOPORUČUJEME části Egejského moře. Osmý největší ostrov kaspakno (jehněčí), afkos (luštěnina) a čerstvé nebojte se pronajmout si auto Řecka. V řecké mytologii je právě tento rybí speciality. nebo motorku a vyražte za poznáním ostrov domovem řeckého boha ohně panenské přírody na ostrově, Héfaista a nalézá se zde jeho pověstná dílna. Ostrov Limnos je ideálním cílem pro klidnou narazíte na úžasné přírodní skvosty, dovolenou – najdete tu „sváteční“ tempo života, místa s dech beroucími Ostrov čítá asi 35 vesnic a měst. Nejbližším relaxaci, odpočinek, krásnou přírodu, nádherné a nezapomenutelnými výhledy bodem k řecké pevnině je tzv. „třetí prst“ pláže, vynikající kuchyni, přátelské místní jako milou pozornost, dáreček poloostrova Chalkidiki a to výběžek Athos. obyvatele a velmi zajímavá místa k poznávání. nebo suvenýr můžete pořídit Za jasného slunného počasí je z Limnosu na ostrově zdejší vínko, tsipouro, na Athos velice dobrá viditelnost. Na 259 km Pokud máte v plánu pronajmout si auto nebo med a sýry z kozího i ovčího mléka se rozkládá členité pobřeží plné nádherných motorku na více dnů a poznat ostrov důkladně, dle prastarých receptur zálivů a mysů, na druhé straně i dvou rozlehlých označte si na mapě tato zajímavá místa: Atsiki, navštivte během pobytu tradiční propastí – Bourni na severu a Moudros na jihu. Agios Demetrios, Agia Sofia, Agios Efstratios, tavernu či restauraci a dopřejte Agaryones, Dafni, Fysini, Kaspakas, Kontias, si typické řecké meze, nejlepší tavernu Na ostrově se nachází několik znamenitých Kontopouli, Kaminia, Kalliopi, Kotsinas, Kornos, poznáte vždy podle toho, kde je nejvíce zlatých pláží, celé pobřeží ostrova jich lemuje Kallithea, Karpasi, Katalakko, Livadochori, místních lidí. -

PROBABILISTIC SEISMIC HAZARD ASSESSMENT (PSHA) for LESVOS Correspondence To: ISLAND USING the LOGIC TREE APPROACH N

Volume 55 BGSG Research Paper PROBABILISTIC SEISMIC HAZARD ASSESSMENT (PSHA) FOR LESVOS Correspondence to: ISLAND USING THE LOGIC TREE APPROACH N. Vavlas [email protected] Nikolaos Vavlas¹, Anastasia Kiratzi¹, Basil Margaris², George Karakaisis¹ DOI number: http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/ ¹ Department of Geophysics, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, bgsg.20705 Greece, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: ² Institute of Earthquake Engineering and Engineering Seismology, EPPO, 55102 PSHA, Lesvos, Thessaloniki, Greece, [email protected] earthquake, logic tree, seismic hazard Citation: Vavlas, Ν, A. Kiratzi, B. Abstract Margaris, G. Karakaisis (2019), Probabilistic seismic hazard assessment We carry out a probabilistic seismic hazard assessment (PSHA) for Lesvos Island, in (PSHA) for Lesvos island the northeastern Aegean Sea. Being the most populated island in the northern Aegean using the logic tree approach, Bulletin Sea and hosting the capital of the prefecture, its seismic potential has significant social- Geological Society of economic meaning. For the seismic hazard estimation, the newest version of the R- Greece, v.55, 109-136. CRISIS module, which has high efficiency and flexibility in model selection, is used. We Publication History: incorporate into the calculations eight (8) ground motion prediction equations Received: 29/06/2019 Accepted: 16/10/2019 (GMPEs). The measures used are peak ground acceleration, (PGA), peak ground Accepted article online: velocity, (PGV), and spectral acceleration, (SA), at T=0.2 sec representative of the 18/10/2019 building stock. We calculate hazard curves for selected sites on the island, sampling the The Editor wishes to thank southern and northern parts: Mytilene, the capital, the village of Vrisa, Mithymna and two anonymous reviewers for their work with the Sigri. -

1 the Turks and Europe by Gaston Gaillard London: Thomas Murby & Co

THE TURKS AND EUROPE BY GASTON GAILLARD LONDON: THOMAS MURBY & CO. 1 FLEET LANE, E.C. 1921 1 vi CONTENTS PAGES VI. THE TREATY WITH TURKEY: Mustafa Kemal’s Protest—Protests of Ahmed Riza and Galib Kemaly— Protest of the Indian Caliphate Delegation—Survey of the Treaty—The Turkish Press and the Treaty—Jafar Tayar at Adrianople—Operations of the Government Forces against the Nationalists—French Armistice in Cilicia—Mustafa Kemal’s Operations—Greek Operations in Asia Minor— The Ottoman Delegation’s Observations at the Peace Conference—The Allies’ Answer—Greek Operations in Thrace—The Ottoman Government decides to sign the Treaty—Italo-Greek Incident, and Protests of Armenia, Yugo-Slavia, and King Hussein—Signature of the Treaty – 169—271 VII. THE DISMEMBERMENT OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE: 1. The Turco-Armenian Question - 274—304 2. The Pan-Turanian and Pan-Arabian Movements: Origin of Pan-Turanism—The Turks and the Arabs—The Hejaz—The Emir Feisal—The Question of Syria—French Operations in Syria— Restoration of Greater Lebanon—The Arabian World and the Caliphate—The Part played by Islam - 304—356 VIII. THE MOSLEMS OF THE FORMER RUSSIAN EMPIRE AND TURKEY: The Republic of Northern Caucasus—Georgia and Azerbaïjan—The Bolshevists in the Republics of Caucasus and of the Transcaspian Isthmus—Armenians and Moslems - 357—369 IX. TURKEY AND THE SLAVS: Slavs versus Turks—Constantinople and Russia - 370—408 2 THE TURKS AND EUROPE I THE TURKS The peoples who speak the various Turkish dialects and who bear the generic name of Turcomans, or Turco-Tatars, are distributed over huge territories occupying nearly half of Asia and an important part of Eastern Europe. -

REPORT on CROP LANDRACES, CROP WILD RELATIVES and WILD HERBS (Including Medicinal and Aromatic Plants) Terra Lemnia Project / Strategy 1.1 / Activity 1.1.2

REPORT ON CROP LANDRACES, CROP WILD RELATIVES AND WILD HERBS (including medicinal and aromatic plants) terra lemnia project / STRATEGY 1.1 / ACTIVITY 1.1.2 Editors: Prof. Dr. PENELOPE BEBELI Agricultural University of Athens DIMITRA GRIGOROPOULOU Agronomist, MedINA Terra Lemnia collaborator SOFIA KYRIAKOULEA Ph.D. student, Agricultural University of Athens Updated Version DANAE SFAKIANOU Agronomist, MedINA Terra Lemnia collaborator December 2020 Dr. RICOS THANOPOULOS Agricultural University of Athens REPORT ON CROP LANDRACES, CROP WILD RELATIVES AND WILD HERBS (including medicinal and aromatic plants) terra lemnia project / STRATEGY 1.1 / ACTIVITY 1.1.2 Updated Version December 2020 EDITORS: Prof. Dr. PENELOPE BEBELI Agricultural University of Athens DIMITRA GRIGOROPOULOU Agronomist, MedINA Terra Lemnia collaborator SOFIA KYRIAKOULEA Ph.D. student, Agricultural University of Athens DANAE SFAKIANOU Agronomist, MedINA Terra Lemnia collaborator Dr. RICOS THANOPOULOS Agricultural University of Athens Coordinated by: Funded by: terra lemnia project | www.terra-lemnia.net MAVA 2017-2022 Mediterranean Strategy Outcome M6 Loss of biodiversity by abandonment of cultural practices Acknowledgements Professor Penelope Bebeli would like to acknowledge the support of Tilemachos Chatzigeorgiou, Aggeliki Petraki, Konstantina Argyropoulou and George Dimitropoulos in editing the text of this report. We acknowledge the contribution of Assistant Professor Maria Panitsa, Professor Erwin Bergmeier and Dr. Stefan Meyer in the identification of wild species as well as for providing the catalogue of the recorded Lemnian species. The authors would like to thank Ivy Nanopoulou and Dimitrios Papageorgiou for their participation in the expedition of 2018. The authors would also like to thank Anemoessa (Association for the Protection of the Environment and Architectural Heritage of Lemnos Island) and MedINA for their overall support in this endeavour. -

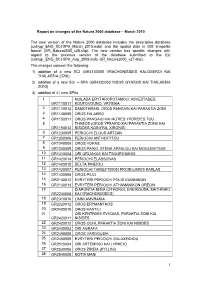

Report on Changes of the Natura 2000 Database – March 2010 the New

Report on changes of the Natura 2000 database – March 2010 The new version of the Natura 2000 database includes the descriptive database (cntrygr_ENG_SCI-SPA_March_2010.mdb) and the spatial data in GIS shapefile format (GR_Natura2000_v28.shp). The new version has specific changes with regard to the previous version of the database submitted to the EU (cntrygr_ENG_SCI-SPA_Aug_2009.mdb, GR_Natura2000_v27.shp). The changes concern the following: 1) addition of a new SCI (GR4130005 VRACHONISIDES KALOGEROI KAI THALASSIA ZONI) 2) addition of a new SCI – SPA (GR4220033 NISOS GYAROS KAI THALASSIA ZONI) 3) addition of 41 new SPAs 1 KOILADA ERYTHROPOTAMOU: ASVESTADES, GR1110011 KOUFOVOUNO, VRYSIKA 2 GR1110012 SAMOTHRAKI: OROS FENGARI KAI PARAKTIA ZONI 3 GR1140009 OROS FALAKRO 4 GR1150011 OROS PANGAIO KAI NOTIES YPOREIES TOU 5 THASOS (OROS YPSARIO KAI PARAKTIA ZONI) KAI GR1150012 NISIDES KOINYRA, XIRONISI 6 GR1230005 PERIOCHI ELOUS ARTZAN 7 GR1230006 PERIOCHI ANTHOFYTOU 8 GR1240008 OROS VORAS 9 GR1240009 OROS PAIKO, STENA APSALOU KAI MOGLENITSAS 10 GR1310004 ORI ORLIAKAS KAI TSOURGIAKAS 11 GR1420014 PERIOCHI ELASSONAS 12 GR1420015 DELTA PINEIOU 13 GR1430007 PERIOCHI TAMIEFTIRON PROIN LIMNIS KARLAS 14 GR1430008 OROS PILIO 15 GR2130012 EVRYTERI PERIOCHI POLIS IOANNINON 16 GR2130013 EVRYTERI PERIOCHI ATHAMANIKON OREON 17 DIAPONTIA NISIA (OTHONOI, EREIKOUSA, MATHRAKI GR2230008 KAI VRACHONISIDES) 18 GR2310016 LIMNI AMVRAKIA 19 GR2320012 OROS ERYMANTHOS 20 GR2420010 OROS KANTILI 21 ORI KENTRIKIS EVVOIAS, PARAKTIA ZONI KAI GR2420011 NISIDES 22 GR2420012 -

Greek-Australian Alliance 1899

GREEK-AUSTRALIAN ALLIANCE 1899 - 2016 100th Anniversary Macedonian Front 75th Anniversary Battles of Greece and Crete COURAGE SACRIFICE MATESHIP PHILOTIMO 1899 -1902 – Greek Australians Frank Manusu (above), Constantine Alexander, Thomas Haraknoss, Elias Lukas and George Challis served with the colonial forces in the South African Boer War. 1912 - 1913 – Australian volunteers served in the Royal Hellenic Forces in the Balkans Wars. At the outbreak of the Second Balkan War in 1913, John Thomas Woods of the St John Ambulance volunteered for service with the Red Cross, assisting the Greek Medical Corps at Thessaloniki, a service for which he was recognised with a Greek medal by King Constantine of Greece. 1914 - 1918 – Approximately 90 Greek Australians served on Gallipoli and the Western Front. Some were born in Athens, Crete, Castellorizo, Kythera, Ithaca, Peloponnesus, Samos, and Cephalonia, Lefkada and Cyprus and others in Australia. They were joined by Greek Australian nurses, including Cleopatra Johnson (Ioanou), daughter of Antoni Ioanou, gold miner of Moonan Brook, NSW. One of 13 Greek Australian Gallipoli veterans, George Cretan (Bikouvarakis) was born in Kefalas, Crete in 1888 and migrated to Sydney in 1912. On the left in Crete, 1910 and middle in Sydney 1918 wearing his Gallipoli Campaign medals. Right, Greek Australian Western Front veteran Joseph Morris (Sifis Voyiatzis) of Cretan heritage. PAGE 2 1915, 4th March – The first Anzacs landed on Lemnos Island, in Moudros Harbour and were part of the largest armada ever assembled at that time. The island served as the main base of operations for the Gallipoli Campaign, including hospitals. In the waters around Lemnos and the island’s soil now rest over 220 Anzacs. -

THE IMPERIAL QUARTER to a Major Extent, the Latin Emperors Modelled

CHAPTER THREE THE IMPERIAL QUARTER To a major extent, the Latin emperors modelled their emperorship ideologically on the Byzantine example, while at the same time signifi- cant Western influences were also present. But how did they actually develop the concrete administrative organization of their empire? The constitutional pact of March 1204 established the contours within which this imperial administration was to be constructed. The starting point of the convention meant a drastic change with regard to Byzantine administrative principles. A fundamental aspect was the feudalization and the theoretical division of the Byzantine Empire into three large regions. One-quarter of the territory was allotted directly to the Latin Emperor. Three-eights were allotted to the non-Venetian and three- eights to the Venetian component of the crusading army. Both regions were to be feudally dependent upon the emperor. In this chapter we examine administrative practice in the imperial quarter. The Location of the Imperial Quarter The imperial domain encompassed five-eighths of the capital Cons- tantinople: the imperial quarter plus the non-Venetian crusaders’ sec- tion. It is true that the March 1204 agreement allotted only the Great Palace—designated as the Boukoleon palace—and the Blacherna pal- ace to the emperor, which implied that the rest of the city should have been divided up according to the established distribution formula, but in practice there is not a single indication to be found that part of the city (three-eighths) was to be allotted to the non-Venetian crusaders in the form of a separate enclave with administrative autonomy from the imperial quarter.1 Apparently, the definitive distribution agree- ment stipulated that five-eighths of Constantinople was to fall to the emperor or, de facto, this was the situation there.2 1 Prevenier, De oorkonden, II, no 267. -

Euboea and Athens

Euboea and Athens Proceedings of a Colloquium in Memory of Malcolm B. Wallace Athens 26-27 June 2009 2011 Publications of the Canadian Institute in Greece Publications de l’Institut canadien en Grèce No. 6 © The Canadian Institute in Greece / L’Institut canadien en Grèce 2011 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Euboea and Athens Colloquium in Memory of Malcolm B. Wallace (2009 : Athens, Greece) Euboea and Athens : proceedings of a colloquium in memory of Malcolm B. Wallace : Athens 26-27 June 2009 / David W. Rupp and Jonathan E. Tomlinson, editors. (Publications of the Canadian Institute in Greece = Publications de l'Institut canadien en Grèce ; no. 6) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-9737979-1-6 1. Euboea Island (Greece)--Antiquities. 2. Euboea Island (Greece)--Civilization. 3. Euboea Island (Greece)--History. 4. Athens (Greece)--Antiquities. 5. Athens (Greece)--Civilization. 6. Athens (Greece)--History. I. Wallace, Malcolm B. (Malcolm Barton), 1942-2008 II. Rupp, David W. (David William), 1944- III. Tomlinson, Jonathan E. (Jonathan Edward), 1967- IV. Canadian Institute in Greece V. Title. VI. Series: Publications of the Canadian Institute in Greece ; no. 6. DF261.E9E93 2011 938 C2011-903495-6 The Canadian Institute in Greece Dionysiou Aiginitou 7 GR-115 28 Athens, Greece www.cig-icg.gr THOMAS G. PALAIMA Euboea, Athens, Thebes and Kadmos: The Implications of the Linear B References 1 The Linear B documents contain a good number of references to Thebes, and theories about the status of Thebes among Mycenaean centers have been prominent in Mycenological scholarship over the last twenty years.2 Assumptions about the hegemony of Thebes in the Mycenaean palatial period, whether just in central Greece or over a still wider area, are used as the starting point for interpreting references to: a) Athens: There is only one reference to Athens on a possibly early tablet (Knossos V 52) as a toponym a-ta-na = Ἀθήνη in the singular, as in Hom. -

New Species of Dolichopoda Bolívar, 1880 (Orthoptera, Rhaphidophoridae) from the Aegean Islands of Andros, Paros and Kinaros (Greece)

DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION : Bruno David Président du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle RÉDACTRICE EN CHEF / EDITOR-IN-CHIEF : Laure Desutter-Grandcolas ASSISTANTS DE RÉDACTION / ASSISTANT EDITORS : Anne Mabille ([email protected]), Emmanuel Côtez MISE EN PAGE / PAGE LAYOUT : Anne Mabille COMITÉ SCIENTIFIQUE / SCIENTIFIC BOARD : James Carpenter (AMNH, New York, États-Unis) Maria Marta Cigliano (Museo de La Plata, La Plata, Argentine) Henrik Enghoff (NHMD, Copenhague, Danemark) Rafael Marquez (CSIC, Madrid, Espagne) Peter Ng (University of Singapore) Norman I. Platnick (AMNH, New York, États-Unis) Jean-Yves Rasplus (INRA, Montferrier-sur-Lez, France) Jean-François Silvain (IRD, Gif-sur-Yvette, France) Wanda M. Weiner (Polish Academy of Sciences, Cracovie, Pologne) John Wenzel (The Ohio State University, Columbus, États-Unis) COUVERTURE / COVER : Female habitus of Dolichopoda kikladica Di Russo & Rampini, n. sp. Photo by G. Anousakis. Zoosystema est indexé dans / Zoosystema is indexed in: – Science Citation Index Expanded (SciSearch®) – ISI Alerting Services® – Current Contents® / Agriculture, Biology, and Environmental Sciences® – Scopus® Zoosystema est distribué en version électronique par / Zoosystema is distributed electronically by: – BioOne® (http://www.bioone.org) Les articles ainsi que les nouveautés nomenclaturales publiés dans Zoosystema sont référencés par / Articles and nomenclatural novelties published in Zoosystema are referenced by: – ZooBank® (http://zoobank.org) Zoosystema est une revue en flux continu publiée par les Publications scientifiques du Muséum, Paris / Zoosystema is a fast track journal published by the Museum Science Press, Paris Les Publications scientifiques du Muséum publient aussi / The Museum Science Press also publish: Adansonia, Anthropozoologica, European Journal of Taxonomy, Geodiversitas, Naturae. Diffusion – Publications scientifiques Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle CP 41 – 57 rue Cuvier F-75231 Paris cedex 05 (France) Tél.