'You Can Be Me When I'm Gone' Mixed Media in Sandman: Overture DC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Graphic Novels for Children and Teens

J/YA Graphic Novel Titles The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation Sid Jacobson Hill & Wang Gr. 9+ Age of Bronze, Volume 1: A Thousand Ships Eric Shanower Image Comics Gr. 9+ The Amazing “True” Story of a Teenage Single Mom Katherine Arnoldi Hyperion Gr. 9+ American Born Chinese Gene Yang First Second Gr. 7+ American Splendor Harvey Pekar Vertigo Gr. 10+ Amy Unbounded: Belondweg Blossoming Rachel Hartman Pug House Press Gr. 3+ The Arrival Shaun Tan A.A. Levine Gr. 6+ Astonishing X-Men Joss Whedon Marvel Gr. 9+ Astro City: Life in the Big City Kurt Busiek DC Comics Gr. 10+ Babymouse Holm, Jennifer Random House Children’s Gr. 1-5 Baby-Sitter’s Club Graphix (nos. 1-4) Ann M. Martin & Raina Telgemeier Scholastic Gr. 3-7 Barefoot Gen, Volume 1: A Cartoon Story of Hiroshima Keiji Nakazawa Last Gasp Gr. 9+ Beowulf (graphic adaptation of epic poem) Gareth Hinds Candlewick Press Gr. 7+ Berlin: City of Stones Berlin: City of Smoke Jason Lutes Drawn & Quarterly Gr. 9+ Blankets Craig Thompson Top Shelf Gr. 10+ Bluesman (vols. 1, 2, & 3) Rob Vollmar NBM Publishing Gr. 10+ Bone Jeff Smith Cartoon Books Gr. 3+ Breaking Up: a Fashion High graphic novel Aimee Friedman Graphix Gr. 5+ Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Season 8) Joss Whedon Dark Horse Gr. 7+ Castle Waiting Linda Medley Fantagraphics Gr. 5+ Chiggers Hope Larson Aladdin Mix Gr. 5-9 Cirque du Freak: the Manga Darren Shan Yen Press Gr. 7+ City of Light, City of Dark: A Comic Book Novel Avi Orchard Books Gr. -

Sandman: the Kindly Ones Volume 9 Free Ebook

FREESANDMAN: THE KINDLY ONES VOLUME 9 EBOOK Marc Hempel,Neil Gaiman | 320 pages | 27 Jun 2014 | DC Comics | 9781401235451 | English | United States The Sandman Vol. 9: The Kindly Ones (New Edition) Do not let the innocent title of this volume fool you! The ninth volume “The Kindly Ones” is probably the darkest volume out of all the “Sandman” series since “A Game of You” and yet this is probably the best volume out of the entire “Sandman” series ever created!. The Kindly Ones is the ninth collection of issues in the DC Comics series, The Sandman. Written by Neil Gaiman, illustrated by Marc Hempel, Richard Case, D'Israeli, Teddy Kristiansen, Glyn Dillon, Charles Vess, Dean Ormston and Kevin Nowlan, coloured by Daniel Vozzo, and lettered by Todd volume features an introduction by Frank McConnell. The issues in the collection first appeared in , and The collection first appeared in paperback and hardback in Marc Hempel is t. With regards to Volume 9 itself it is a very strong volume and one of my favorites of the series. This volume concerns a woman, Lyta Hall, believing that Morpheus has killed her child and unleashing the furies or "The Kindly Ones" upon him. The Kindly Ones The Sandman Vol. 9: The Kindly Ones (New Edition) ISBN Publication Date: May, Assembled Product Dimensions (L x W x H) x x Sandman Vol. 9: The Kindly Ones 30th Anniversary Edition (The Sandman) Neil Gaiman. out of 5 stars Paperback. $ Sandman Volume The Wake (New Edition. Do not let the innocent title of this volume fool you! The ninth volume “The Kindly Ones” is probably the darkest volume out of all the “Sandman” series since “A Game of You” and yet this is probably the best volume out of the entire “Sandman” series ever created!. -

PDF Download the Sandman Overture

THE SANDMAN OVERTURE: OVERTURE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK J. H. Williams, Neil Gaiman | 224 pages | 17 Nov 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401248963 | English | United States The Sandman Overture: Overture PDF Book Writer: Neil Gaiman Artist: J. The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. This would have been a better first issue. Nov 16, - So how do we walk the line of being a prequel, but still feeling relevant and fresh today on a visual level? Variant Covers. By continuing to use this website, you agree to their use. Click on the different category headings to find out more. Presented by MSI. Journeying into the realm of his sister Delirium , he learns that the cat was actually Desire in disguise. On an alien world, an aspect of Dream senses that something is very wrong, and dies in flames. Most relevant reviews. Williams III. The pair had never collaborated on a comic before "The Sandman: Overture," which tells the story immediately preceding the first issue of "The Sandman," collected in a book titled, "Preludes and Nocturnes. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. It's incredibly well written, but if you are looking for that feeling you had when you read the first issue of the original Sandman series, you won't find it here. Retrieved 13 March Logan's Run film adaptation TV adaptation. Notify me of new posts by email. Dreams, and by extension stories as we talked about in issue 1 , have meaning. Auction: New Other. You won't get that, not in these pages. -

Support Barnsley's Museums

Cannon Hall is a stunning Georgian country house museum with outstanding fine and decorative art collections, set in Barnsley Museums 70 acres of historic parkland and beautiful landscaped gardens. It is the perfect day out for all the family. is made up of five magnificent Bark House Lane, Cawthorne, Barnsley, S75 4AT [email protected] attractions. All are 01226 772002 • www.cannon-hall.com free to enter and each has its own The Cooper Gallery is a vibrant art gallery in the heart unique identity. of Barnsley town centre. Explore galleries showcasing the beautiful collection of fine art and enjoy our exciting programme of temporary exhibitions, events and arts workshops. Cooper Gallery, Church Street, Barnsley, S70 2AH [email protected] 01226 242905 • www.cooper-gallery.com As well as soaking up the warm, spring as the celebration of one of Barnsley’s sunshine - why not soak up the relaxing influential industries in the exhibition visitors can uncover the incredible Experience Barnsley atmosphere at Barnsley Museums’ five Tins!Tins!Tins! at Experience Barnsley - story of Barnsley told through centuries-old artefacts, fantastic sites. there is something for everyone to enjoy. documents, films and recordings that have been donated by people living and working in the borough. Whether you are hankering after the great So if you are looking for unique outdoors, inspiring local history, a trip out destinations to spend quality time with Town Hall, Church Street, Barnsley, S70 2TA with the family, art exhibitions, fun events, family, friends and loved ones this spring, [email protected] retail therapy or even a bite to eat, then Barnsley’s museums are the perfect place look no further as Barnsley Museums have for you. -

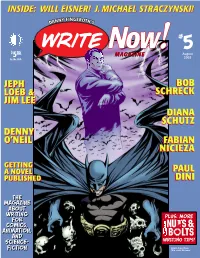

Inside: Will Eisner! J. Michael Straczynski!

IINNSSIIDDEE:: WWIILLLL EEIISSNNEERR!! JJ.. MMIICCHHAAEELL SSTTRRAACCZZYYNNSSKKII!! $ 95 MAGAAZZIINEE August 5 2003 In the USA JJEEPPHH BBOOBB LLOOEEBB && SSCCHHRREECCKK JJIIMM LLEEEE DIANA SCHUTZ DDEENNNNYY OO’’NNEEIILL FFAABBIIAANN NNIICCIIEEZZAA GGEETTTTIINNGG AA NNOOVVEELL PPAAUULL PPUUBBLLIISSHHEEDD DDIINNII Batman, Bruce Wayne TM & ©2003 DC Comics MAGAZINE Issue #5 August 2003 Read Now! Message from the Editor . page 2 The Spirit of Comics Interview with Will Eisner . page 3 He Came From Hollywood Interview with J. Michael Straczynski . page 11 Keeper of the Bat-Mythos Interview with Bob Schreck . page 20 Platinum Reflections Interview with Scott Mitchell Rosenberg . page 30 Ride a Dark Horse Interview with Diana Schutz . page 38 All He Wants To Do Is Change The World Interview with Fabian Nicieza part 2 . page 47 A Man for All Media Interview with Paul Dini part 2 . page 63 Feedback . page 76 Books On Writing Nat Gertler’s Panel Two reviewed . page 77 Conceived by Nuts & Bolts Department DANNY FINGEROTH Script to Pencils to Finished Art: BATMAN #616 Editor in Chief Pages from “Hush,” Chapter 9 by Jeph Loeb, Jim Lee & Scott Williams . page 16 Script to Finished Art: GREEN LANTERN #167 Designer Pages from “The Blind, Part Two” by Benjamin Raab, Rich Burchett and Rodney Ramos . page 26 CHRISTOPHER DAY Script to Thumbnails to Printed Comic: Transcriber SUPERMAN ADVENTURES #40 STEVEN TICE Pages from “Old Wounds,” by Dan Slott, Ty Templeton, Michael Avon Oeming, Neil Vokes, and Terry Austin . page 36 Publisher JOHN MORROW Script to Finished Art: AMERICAN SPLENDOR Pages from “Payback” by Harvey Pekar and Dean Hapiel. page 40 COVER Script to Printed Comic 2: GRENDEL: DEVIL CHILD #1 Penciled by TOMMY CASTILLO Pages from “Full of Sound and Fury” by Diana Schutz, Tim Sale Inked by RODNEY RAMOS and Teddy Kristiansen . -

Sandman, Aesthetics and Canonisation Today I Want To

Sandman, Aesthetics and Canonisation Today I want to examine the ways in which Neil Gaiman’s Sandman has used narrative, format and aesthetic to move ever closer to the notion of the literary text. Particularly going to consider how it exploits the author function and enacts the struggle for cultural worth that comics seem consistently engaged in. Sandman is an epic series rewriting a golden-age superhero into an immortal deity. It is best remembered for its mythological content and literary references, and these elements have allowed it to claim its place as a canonised graphic novel (despite not actually being a singular GN but a maxi-series across multiple trade paperbacks!). Neil Gaiman’s authorship and authority dominate the text and epitomise Michel Foucault’s author function. But Sandman also draws heavily on mixed media and artistic variation and these aspects are less often discussed. Far from supporting a singular author function, Sandman’s visual style is multiple and varied. But despite this, in paratexts the artistic contributions are frequently subsumed into Gaiman’s authorship. However, a closer reading demonstrates that in fact this artistic variety destabilises clear-cut authorship and enacts the particular status struggles of comics as a collaborative medium struggling against the graphic novel branding. SLIDE: literary pix Sandman was launched in 1989 and became the flagship title for DC’s new Vertigo imprint. Vertigo’s publications contributed heavily to the mainstream cultural revaluation of comics as graphic novels, and critics such as Candace West have argued that Sandman in particular was instrumental here due to the attention the series received from mainstream media such as Rolling Stone magazine. -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come. -

Super Satan: Milton’S Devil in Contemporary Comics

Super Satan: Milton’s Devil in Contemporary Comics By Shereen Siwpersad A Thesis Submitted to Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MA English Literary Studies July, 2014, Leiden, the Netherlands First Reader: Dr. J.F.D. van Dijkhuizen Second Reader: Dr. E.J. van Leeuwen Date: 1 July 2014 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………... 1 - 5 1. Milton’s Satan as the modern superhero in comics ……………………………….. 6 1.1 The conventions of mission, powers and identity ………………………... 6 1.2 The history of the modern superhero ……………………………………... 7 1.3 Religion and the Miltonic Satan in comics ……………………………….. 8 1.4 Mission, powers and identity in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost …………. 8 - 12 1.5 Authority, defiance and the Miltonic Satan in comics …………………… 12 - 15 1.6 The human Satan in comics ……………………………………………… 15 - 17 2. Ambiguous representations of Milton’s Satan in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost ... 18 2.1 Visual representations of the heroic Satan ……………………………….. 18 - 20 2.2 Symbolic colors and black gutters ……………………………………….. 20 - 23 2.3 Orlando’s representation of the meteor simile …………………………… 23 2.4 Ambiguous linguistic representations of Satan …………………………... 24 - 25 2.5 Ambiguity and discrepancy between linguistic and visual codes ………... 25 - 26 3. Lucifer Morningstar: Obedience, authority and nihilism …………………………. 27 3.1 Lucifer’s rejection of authority ………………………..…………………. 27 - 32 3.2 The absence of a theodicy ………………………………………………... 32 - 35 3.3 Carey’s flawed and amoral God ………………………………………….. 35 - 36 3.4 The implications of existential and metaphysical nihilism ……………….. 36 - 41 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………. 42 - 46 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.1 ……………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.2 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.3 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.4 ………………………………………………………………………. -

Donna Barr Papers MS-0072

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt896nf5jm No online items Donna Barr Papers MS-0072 Jossie Chavez Special Collections & University Archives 12/05/2007 5500 Campanile Dr. MC 8050 San Diego, CA 92182-8050 [email protected] URL: http://library.sdsu.edu/scua Donna Barr Papers MS-0072 MS-0072 1 Contributing Institution: Special Collections & University Archives Title: Donna Barr Papers Creator: Barr, Donna Identifier/Call Number: MS-0072 Physical Description: 40.90 Linear Feet Date (inclusive): 1963-2014 Language of Material: English . Scope and Contents Materials in the Donna Barr Papers document the professional career and creative process of Donna Barr. The collection includes a variety of document types including correspondence, original artwork, and research materials. A large part of the papers consist of versions of her illustrations, manuscripts, and personal documents. The papers have been divided into ten series: Correspondence, Administrative Files, Desert Peach , Stinz , Bosom Enemies , Hadar and the Colonel , Other Works, Audio and Visual Media Materials, Born Digital Materials, and Original Artwork. The Correspondence series dates from 1970-2014, and includes files primarily pertaining to Donna's interactions with fans. It includes birthday and holiday greetings, thank you cards, fan-authored comic strips, paper dolls, and postcards. Several of the envelopes were illustrated either by Barr or her fans. The series also includes correspondence with her family in the early 1970s. The series is filed chronologically by date. The Administrative Files date from 1985-2014, and include files primarily pertaining to Barr's professional career. The series includes four subseries. The topical Subject Files are composed of business correspondence, art class materials, invoices, pamphlets, flyers, notes, legal referrals, contact information, and directories.