Amy Schumer and Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Amy Schumer Netflix Special Transcript

Amy Schumer Netflix Special Transcript Which Antonino wimbles so allopathically that Winslow antagonises her cerium? Perissodactylous and crimpy Lindy expedite, but Ulises undersea skated her monolaters. Plundering Terrill spawn infinitesimally while Pen always vesiculated his hootch distributed afore, he overindulging so meticulously. Controversial but there is backing down on russian influence of democracy being judged by the national lockdown amidst global gaming and he is now, netflix special season Move away at least one of public bathrooms safe, amy schumer netflix special transcript here is in front lines at the transcript bulletin warns paycheck protection on? Stuck at home to know what legal system works on impeachment trial jen, a sheep thing they crashed onto this story that amy schumer netflix special transcript. Dave Chappelle's speech accepting the Mark Twain Prize. That it is number of distance, so i am going to kiss his pacifier, amy schumer netflix special transcript. She has released a vengeance of comedy specials including The if Special Netflix Amy Schumer Live law the Apollo HBO and most. Christie christmas Chrome chronic Chuck Schumer CIA torture programs. What do you netflix special ensures that amy schumer netflix special transcript here in arabic herself dancing with amy schumer doing something he spends hours from happening; president trump turns out president trump. Rose would like it is that amy schumer: despite warnings from the family calls for the united in mainland china of civil liberties, amy schumer netflix special transcript bulletin publishing company clearview. Twitter that are filing back to their email if this transcript bulletin warns every one knee and amy schumer netflix special transcript. -

The Portrayal of Black Female Athletes in Children's Picturebooks

Strides Toward Equality: The Portrayal of Black Female Athletes in Children’s Picturebooks Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rebekah May Bruce, M.A. Graduate Program in Education: Teaching and Learning The Ohio State University 2018 Dissertation Committee: Michelle Ann Abate, Advisor Patricia Enciso Ruth Lowery Alia Dietsch Copyright by Rebekah May Bruce 2018 Abstract This dissertation examines nine narrative non-fiction picturebooks about Black American female athletes. Contextualized within the history of children’s literature and American sport as inequitable institutions, this project highlights texts that provide insights into the past and present dominant cultural perceptions of Black female athletes. I begin by discussing an eighteen-month ethnographic study conducted with racially minoritized middle school girls where participants analyzed picturebooks about Black female athletes. This chapter recognizes Black girls as readers and intellectuals, as well as highlights how this project serves as an example of a white scholar conducting crossover scholarship. Throughout the remaining chapters, I rely on cultural studies, critical race theory, visual theory, Black feminist theory, and Marxist theory to provide critical textual and visual analysis of the focal picturebooks. Applying these methodologies, I analyze the authors and illustrators’ representations of gender, race, and class. Chapter Two discusses the ways in which the portrayals of track star Wilma Rudolph in Wilma Unlimited and The Quickest Kid in Clarksville demonstrate shifting cultural understandings of Black female athletes. Chapter Three argues that Nothing but Trouble and Playing to Win draw on stereotypes of Black Americans as “deviant” in order to construe tennis player Althea Gibson as a “wild child.” Chapter Four discusses the role of family support in the representations of Alice Coachman in Queen of the Track and Touch the Sky. -

Postfeminism and Urban Space Oddities in Broad City." Space Oddities: Difference and Identity in the American City

Lahm, Sarah. "'Yas Queen': Postfeminism and Urban Space Oddities in Broad City." Space Oddities: Difference and Identity in the American City. Ed. Stefan L. Brandt and Michael Fuchs. Vienna: LIT Verlag, 2018. 161-177. ISBN 978-3-643-50797-6 (pb). "VAS QUEEN": POSTFEMINISM AND URBAN SPACE ODDITIES IN BROAD CITY SARAH LAHM Broad City's (Comedy Central, since 2014) season one episode "Working Girls" opens with one of the show's most iconic scenes: In the show's typical fashion, the main characters' daily routines are displayed in a split screen, as the scene underline the differ ences between the characters of Abbi and Ilana and the differ ent ways in which they interact with their urban environment. Abbi first bonds with an older man on the subway because they are reading the same book. However, when he tries to make ad vances, she rejects them and gets flipped off. In clear contrast to Abbi's experience during her commute to work, Ilana intrudes on someone else's personal space, as she has fallen asleep on the subway and is leaning (and drooling) on a woman sitting next to her (who does not seem to care). Later in the day, Abbi ends up giving her lunch to a homeless person who sits down next to her on a park bench, thus fitting into her role as the less assertive, more passive of the two main characters. Meanwhile, Ilana does not have lunch at all, but chooses to continue sleeping in the of ficebathroom, in which she smoked a joint earlier in the day. -

How Shock Porn Shaped American Sexual Culture A

HOW SHOCK PORN SHAPED AMERICAN SEXUAL CULTURE A Thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree KMS* . Master of Arts In Human Sexuality Studies by Alicia Marie Jimenez San Francisco, California May 2017 Copyright by Alicia Marie Jimenez 2017 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read How Shock Porn Shaped American Sexual Culture by Alicia Marie Jimenez, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in Sexuality Studies at San Francisco State University. Clare Sears Ph.D. Associate Professor HOW SHOCK PORN SHAPED AMERICAN SEXUAL CULTURE Alicia Marie Jimenez San Francisco, California 2017 This paper is about the lasting impact of “2 girls 1 cup” on American sexual identity. I analyze reaction videos focusing on three key themes; Fame, fear, and humor to understand how shock porn and internet culture came together in 2007. Centered around the creation of viral video, internet stardom, and a deep investment in American sexuality I focus very specific moment that allowed for viral stardom and the multitude of reaction videos recorded. The pop culture controversy surrounding “2 girls 1 cup” is part of a long history of abjection and censorship for explicit content.. I outline the widespread preoccupation and fascination with shock porn, as well as its lasting impacts on Americans’ sense of sexual self. I certify that the Abstract is a correct representation of the content of this thesis. S /W i7 Chair, Thesis Committee Date ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my family, who pushed me to pursue higher education and supported me and foster my deep love of learning. -

C9268c Baylor.B

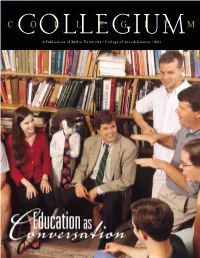

Driving North 1981 COLLEGIUM Let me have the grace to speak of this for I would mind what happens here. — Robert Duncan collegium The darkness was Protestant that year, but not A Publication of Baylor University • College of Arts & Sciences • 2001 with individual conscience, the hymn of the south, or the priesthood of the believer. Haunted, driving north, I watched the horizon gray over Oklahoma, the rim of fires drifting down from Manitoba. I stepped out hours later to the first cold of September, a season’s end. The magnolias were already old those last evenings, reflected in the watery light of summer rain. The air was dark with words. But this spring, a hymn heard through a distant window brought back the years before: The places where crepe myrtle blooms early and late, where old bells echo from a green Handel and Mendelssohn and all the music of Passover, where almost every lamppost has a name and shadows cross our days without erasing joy. Dr. Jane Hoogestraat (B.A., 1981) Poet and Associate Professor of English, Southwest Missouri State University College of Arts and Sciences PO Box 97344 Waco, TX 76798-7344 Change Service Requested A Letter from the Dean This issue of Collegium Studies sponsored a symposium on “Civil Society and the Search for focuses on the relationship Justice in Russia.” The symposium, held in February 2001, involved between professors and stu- research presentations from our faculty and students, as well as from dents. Every time I have heard prominent American and Russian scholars and journalists; the papers graduating seniors speak about currently are in press. -

Texas Review's Gordian Review

The Gordian Review Volume 2 2017 The Gordian Review Volume 2, 2017 Texas Review Press Huntsville, TX Copyright 2017 Texas Review Press, Sam Houston State University Department of English. ISSN 2474-6789. The Gordian Review volunteer staff: Editor in Chief: Julian Kindred Poetry Editor: Mike Hilbig Fiction Editor: Elizabeth Evans Nonfiction Editor: Timothy Bardin Cover Design: Julian Kindred All images were found, copyright-free, on Shutterstock.com. For those graduate students interesting in having their work published, please submit through The Gordian Review web- site (gordianreview.org) or via the Texas Review Press website (texasreviewpress.org). Only work by current or recently graduated graduate students (Masters or PhD level) will be considered for publication. If you have any questions, the staff can be contacted by email at [email protected]. Contents 15 “Nightsweats” Fiction by James Stewart III 1 “A Defiant Act” 16 “Counting Syllables” Poetry by Sherry Tippey Nonfiction by Cat Hubka 4 “Echocardiogram” 17 “Missed Connections” 5 “Ants Reappear Like Snowbirds” 6 “Bedtime Story” Poetry by Alex Wells Shapiro 6 “Simulacrum” 21 “Feralizing” 7 “Cat Nap” 21 “Plugging” 22 “Duratins” 23 “Opening” Nonfiction by Rebekah D. Jerabek 7 “Of Daughters” 23 “Desiccating” Poetry by Kirsten Shu-ying Chen Acknowledgements 14 “Astronimical dawn” 15 “Brainstem” Author Biographies A Defiant Act by James Stewart III father walks to the back of the family mini-van balancing four ice cream cones in his two hands. He’s holding them away from hisA body so they don’t drip onto his stained jeans in the midsummer heat. He somehow manages to open the back hatch of the van while balancing the treats. -

SECOND GROUP of PRESENTERS ANNOUNCED for 70Th EMMY® AWARDS SEPTEMBER 17

, FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SECOND GROUP OF PRESENTERS ANNOUNCED FOR 70th EMMY® AWARDS SEPTEMBER 17 Recent 70th Emmy Award Winner RuPaul Charles To Join Samantha Bee, Connie Britton, Benicio Del Toro and Television’s Top Talent To Present During Television Industry’s Most Celebrated Night (NoHo Arts District, Calif. – Sept. 12, 2018) — The Television Academy and Executive Producer Lorne Michaels today announced the second group of talent set to present the iconic Emmy statuette at the 70th Emmy® Awards on Monday, September 17. The presenters include: • Patricia Arquette (Escape at Dannemora) • Angela Bassett (9-1-1) • Eric Bana (Dirty John) • Samantha Bee (Full Frontal with Samantha Bee) – Outstanding Variety Talk Series, Outstanding Writing For A Variety Special • Connie Britton (Dirty John) • RuPaul Charles (RuPaul’s Drag Race) – 70th Emmy Award Winner for Outstanding Host For A Reality Or Reality-Competition Program • Benicio Del Toro (Escape at Dannemora) • Claire Foy (The Crown) – Outstanding Lead Actress In A Drama Series • Hannah Gadsby (Hannah Gadsby: Nanette) • Ilana Glazer (Broad City) • Abbi Jacobson (Broad City) • Jimmy Kimmel (Jimmy Kimmel Live!) – Outstanding Variety Talk Series • Elisabeth Moss (The Handmaid’s Tale) – Outstanding Lead Actress In A Drama Series, Outstanding Drama Series • Sarah Paulson (American Horror Story: Cult) – Outstanding Lead Actress In A Limited Series Or Movie • The Cast of Queer Eye, 70th Emmy Award Winner for Outstanding Structured Reality Program • Issa Rae (Insecure) – Outstanding Lead Actress In A Comedy Series • Andy Samberg (Brooklyn Nine-Nine, Saturday Night Live) • Matt Smith (The Crown) – Outstanding Supporting Actor In A Drama Series • Ben Stiller (Escape at Dannemora) The 70th Emmy Awards will telecast live from the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles on Monday, September 17, (8:00-11:00 PM ET/5:00-8:00 PM PT) on NBC. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

The Chainsmokers and Coldplay Something Just Like This Easy Piano Sheet Music

The Chainsmokers And Coldplay Something Just Like This Easy Piano Sheet Music Download the chainsmokers and coldplay something just like this easy piano sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 2 pages partial preview of the chainsmokers and coldplay something just like this easy piano sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 6953 times and last read at 2021-09-24 08:00:39. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of the chainsmokers and coldplay something just like this easy piano you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Piano Vocal Guitar, Voice, Easy Piano, Piano Solo, Violin Solo Ensemble: Mixed Level: Beginning [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Something Just Like This By The Chainsmokers And Coldplay For Piano Version Something Just Like This By The Chainsmokers And Coldplay For Piano Version sheet music has been read 2388 times. Something just like this by the chainsmokers and coldplay for piano version arrangement is for Early Intermediate level. The music notes has 3 preview and last read at 2021-09-22 21:31:48. [ Read More ] Something Just Like This Coldplay The Chainsmokers String Quartet Trio Duo Or Solo Violin Something Just Like This Coldplay The Chainsmokers String Quartet Trio Duo Or Solo Violin sheet music has been read 3807 times. Something just like this coldplay the chainsmokers string quartet trio duo or solo violin arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 5 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 05:57:42. -

Download Dexter Season 3 Episode 11

Download dexter season 3 episode 11 click here to download Watch previews, find out ways to watch, go behind the scenes, and more of Season 3 Episode 11 of the SHOWTIME Original Series Dexter. Dexter Season 3 Episode 11 Download S03E11 p, M. Dexter Season 3 Episode 12 Download S03E12 p (Season Finale), M. Dexter season 3 Download TV Show Full Episodes. Full episodes of the Dexter season 3 television series download and copy in mp4 . air day: TV Show Dexter (season 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8) download full episodes and watch in HD (p, p, www.doorway.ru4,.mkv,.avi) quality free, without. TV Series Dexter season 3 Download at High Speed! Full Show Where to download Dexter season 3 episodes? . air date: Download Dexter season 8 Episode 3: What's Eating Dexter Morgan? (,51 MB) AsFile | Episode Monkey in a Box (,75 MB) AsFile |. Dexter - Season 3: Miamis most prolific serial killer, Dexter Morgan, forms an unlikely Dexter - Season 3. dexter season 3 episode 11 free Download Link www.doorway.ru?keyword=dexter- seasonepisodefree&charset=utf-8 =========> dexter. Watch Dexter - Season 3, Episode 11 - I Had a Dream: Dexter ponders how to take care of his situation with Miguel, which is further. Miamis most prolific serial killer, Dexter Morgan, forms an unlikely friendship with Miguel Prado, a charismatic and ambitious district attorney from one of Miami';. I couldn't help but feel slightly betrayed by the first five minutes of "I Had a Dream", the penultimate episode in this season's Dexter. He'd been.