Get Free PDF Version with 75 Illustrations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Wstory of Forbvsic Detect1ow Coun Wilson

WRITTEN IN BLOOD A WSTORY OF FORBVSIC DETECT1OW COUN WILSON & DÄMON WILSON ROBINSON London Analytical Table of Contents Acknowledgements xiii Introduction 1 A Japanese Sherlock Holmes. Suicide or murder? 'Hesitation injuries.' Problems of writing a history of scientific crime detection. 1 The Science of Detection 7 The Nancy Titterton case: solved by a horse's hair. The case of Mary Rogers, the New York 'cigar girl'. Poe's theory of the killer. The true solution. Dupin as the founder of scientific detecfion. The murder of Helen Jewett. Conan Doyle creates Sherlock Holmes. The 'needle-in- the-hayStack' method - Canler tracks down Lacenaire. Bow Street Runner Henry Goddard tracks a swindler across America. The use of torture. Judge Cambo sentences an innocent man. Miscarriages of justice: the case of the Marquis d'Anglade; the case of Lady Mazel. Henry Goddard and the murder of Elizabeth Longfoot. The murder of the Steward Richardson. Goddard solves a crime by examining the bullet. Crime in eariy centuries: the diary of Master Hans Schmidt, the Nuremberg executioner. London in the eighteenth Century. Moll Cutpurse and Jonathan Wild. Gin and the rising crime rate. The Mohocks. The first efficient magistrate: Sir Thomas De Veil. The murder of Mr Penny. Henry Fielding takes over Bow Street. The Problem of highwaymen. The first recorded example of scientific detection: the case of Richardson. The Mannings murder Patrick O'Connor. The minder of Mrs Millson. Inspector Field and the clue of the dirty gloves. Inspector Whicher and the murder of Francis Kent. The case of Father Hubert Dahme. The public prosecutor disproves his owncase. -

Alton H. Blackington Photograph Collection Finding

Special Collections and University Archives : University Libraries Alton H. Blackington Photograph Collection 1898-1943 15 boxes (4 linear ft.) Call no.: PH 061 Collection overview A native of Rockland, Maine, Alton H. "Blackie" Blackington (1893-1963) was a writer, photojournalist, and radio personality associated with New England "lore and legend." After returning from naval service in the First World War, Blackington joined the staff of the Boston Herald, covering a range of current events, but becoming well known for his human interest features on New England people and customs. He was successful enough by the mid-1920s to establish his own photo service, and although his work remained centered on New England and was based in Boston, he photographed and handled images from across the country. Capitalizing on the trove of New England stories he accumulated as a photojournalist, Blackington became a popular lecturer and from 1933-1953, a radio and later television host on the NBC network, Yankee Yarns, which yielded the books Yankee Yarns (1954) and More Yankee Yarns (1956). This collection of glass plate negatives was purchased by Robb Sagendorf of Yankee Publishing around the time of Blackington's death. Reflecting Blackington's photojournalistic interests, the collection covers a terrain stretching from news of public officials and civic events to local personalities, but the heart of the collection is the dozens of images of typically eccentric New England characters and human interest stories. Most of the images were taken by Blackington on 4x5" dry plate negatives, however many of the later images are made on flexible acetate stock and the collection includes several images by other (unidentified) photographers distributed by the Blackington News Service. -

Access Magazine, April 2016

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Access Magazine College of Applied Sciences and Arts 4-1-2016 Access Magazine, April 2016 San Jose State University, School of Journalism and Mass Communications Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/accessmagazine Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation San Jose State University, School of Journalism and Mass Communications, "Access Magazine, April 2016" (2016). Access Magazine. 16. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/accessmagazine/16 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Applied Sciences and Arts at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Access Magazine by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ccess MAGAZINE ISSUE 2 April 2016 Uncovering the essence of San Jose Contents From orchards to Apple: From orchards to Apple: More than 200 years of San Jose history 3-5 San Jose sports trifecta timeline 6-7 More than 200 years of The Greek system 8-9 San Jose history Japanese Americans 10 ACCESS STAFF A classical man / Playing with words 11 Article by Kimberly Johnson In order to achieve our goals for Background photo: Courtesy of the SJPL the future, we must examine what took Spring 2016 What a tease! 12 California Room from the Historic Map and On a mission Atlas Collection place to get San Jose here. We must look Trail blazers almost two and a half centuries into an Jose, a city of 1 million people, the past. Editor-in-Chief: Raechel Price The El Camino Real is the 600- is a place where diversity is Historic Route or Auto Tour mile trail taken by the first commonplace and technology is Settlement Route currently demarcates Managing Editor: Rain Stites S Spaniard expedition through hardwired into the community. -

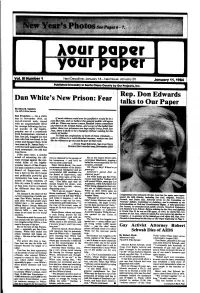

Dan White's New Prison: Fear Rep. Don Edwards Talks to Our Paper

Rep. Don Edwards Dan White’s New Prison: Fear talks to Our Paper By Dion B. Sanders Kfa GPA Wire Service San Francisco — On a chilly day in November 1933, an I f mob violence could ever be justified it would be in a out-of-control mob, siezed case like this, and we believe the general public wiU agree with an unquenchable thirst with us. There was never a more fiendish crime committed for revenge following the bru anywhere in the United States, and we are o f the belief that tal murder of the highly- unless these two prisoners are kept safely away from San popular son of a prominent Jose, there is Ukely to be a hanging without waiting fo r the local businessman, stormed a courts o f Justice. San Jose jail, dragged out two To read the confessions o f both o f these criminals — men who had confessed to the told to officers in a cold-blooded manner, makes one feel crime and hanged them from lik e h e w anted to g o o u t a n d b e p a r t o f th a t m o b . two trees in St. James Park — - , —Front Page Editorial, San Jose News with the tacit approval of the •- Brooke Hart murder'ease, November L933 local newspaper, the old San Jose News. Fifty years later, a similar mood of extracting the ulti forever damned by the people of But at the Castro Street rally, mate revenge against the con his hometown — and he’d be entertainer Blackberri, singing a victed killer of the highly- wise to never come back. -

©2013 Casey Shevlin All Rights Reserved

©2013 CASEY SHEVLIN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A SYSTEM WITH PARTS AND PLAYERS: THE AMERICAN LYNCH MOB IN JOHN STEINBECK’S LABOR TRILOGY A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Casey Shevlin May, 2013 A SYSTEM WITH PARTS AND PLAYERS: THE AMERICAN LYNCH MOB IN JOHN STEINBECK’S LABOR TRILOGY Casey Shevlin Thesis Approved: Accepted: ______________________________ ______________________________ Advisor Dean of College Dr. Patrick Chura Dr. Chand Midha ______________________________ ______________________________ Committee Member Dean of Graduate School Dr. Hillary Nunn Dr. George R. Newkome ______________________________ ______________________________ Committee Member Date Dr. Julie Drew ______________________________ Department Chair Dr. William Thelin ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………………………………iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………1 II. “THEY’RE THE SAME ONES THAT LYNCH NEGROES”: VIGILANTES AND LYNCH MOBS IN STEINBECK’S IN DUBIOUS BATTLE……...…………………....7 III. STEINBECK’S OF MICE AND MEN: A LYNCHING NOVEL……………….….27 IV. STEINBECK’S THE GRAPES OF WRATH: LYNCHING AND RACIAL INSTABILITY IN THE 1930s WEST…………………………………………………..47 V. CONCLUDING THOUGHTS…………………………………..................................67 LITERATURE CITED.………………………………………………………………….71 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 3.1 Life Magazine Photo………………………..........……………………..………..29 iv CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION This thesis will explore the subject of lynching in John Steinbeck’s work, specifically his 1930s labor trilogy: In Dubious Battle (1936), Of Mice and Men (1937), and The Grapes of Wrath (1939). My interest in John Steinbeck’s work and its connection to lynching was sparked by a particular reading of his 1937 novel, Of Mice and Men. I say particular because I have encountered the novel many times. -

Judge Lynch S Cause Cel Bre Fr Ank — Or ( B ) the Mob Was Or Der Ly New Leans Mafia

JUDGELYNCH HIS FIRS T HU N D RED Y EARS BY FRANK SHAY NEWY ORK WASHBU RN IN C. IVES , By th e Same Auth or IRON MEN AN D WOODEN SHIPS MY PIOUS FRIENDS AN D DRUNKEN COMPANIONS ’ HERE S AUDACITY# INCREDIB LE PI#ARRO PIRATE WENCH etc . etc. , JUDGELYNCH HIS FIRS T HU N D RED Y EARS BY FRAN K SHAY N EWY ORK WASHBU RN IN C. IVES , CO IG H 1 8 B Y K H PYR T, 93 , FRAN S AY All rights r eserved P R I N T E D I N T H E U N I T E D S T A T E S O F A M E R I C A - B Y T H E VA I L B A L L O U P RE S S , I N C . , B I N G H A MT O N , N . Y . Carrter m Preface “ TO HELL WITH THE LAW Chapter One THERE WAS A JUDGE NAMED LYNCH Chapter Two THE EARLY LIFE AN D TIMES OF JUDG E LYNCH Chapter Three ’ JUDG E LYNCH S CODE Chapter Four ’ JU DG E LY NCH S JURORS Chapter Five THE JURISDICTION OF JUDG E LYN CH Chapter Six ’ SOME OF JUDG E LYNCH S CASES ’ ’ e — Leo (A) Judge Lynch s Cause Cel bre Fr ank — Or ( B ) The Mob Was Or der ly New leans Mafia w . ( C ) The Bur ning of Henry Lo ry CO N TE N T S (D) The Law Never Had a Chance Claude Neal ( E ) Th e Five Thousandth— Raymond G unn ( F ) Twice Lynche d in Texas— Ge or ge Hughes (G) Thr ee Governors Go Into Action 1 9 3 3 Who D efie d (H) Those the Bo sses ( 1 ) I 9 3 7 Chapter Seven THE REVERSALS OF JUDG E LYNCH L nch -Executions in U ni d S s 1 882— 1 y the te tate , 93 7 Bibliography P r efa ce TO HELL WITH THE LAW LYN CHING has many legal definitions : It means one thing in Kentucky and North Carolina and another in Virginia or Minnesota . -

Memo to the Planning Commission PREVIOUS HEARING DATE: MAY 12, 2016

Memo to the Planning Commission PREVIOUS HEARING DATE: MAY 12, 2016 Date: July 7, 2016 Case No.: 2016-000068IMP Project Address: 800 CHESTNUT STREET Zoning: RH-3 (Residential House, Three-Family) 40-X Height and Bulk District Block/Lot: 0049/001 Project Sponsor: Heather Hickman Holland San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) 800 Chestnut Street San Francisco, CA 94133 Staff Contact: Andrew Perry – (415) 575-9017 [email protected] Recommendation: No Action Necessary – Informational Item BACKGROUND On May 12, 2016, the Planning Commission held a public hearing for receipt of public testimony on the Institutional Master Plan (IMP) for the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI). During the hearing, the Commission requested additional information be included in the IMP document, before it would be considered “accepted”. Specifically, the Commission requested that additional maps and information be provided to give greater context to SFAI’s facilities, with more specific details regarding the student housing provided at 630 Geary St. and 717 Sutter St. and the distances between these buildings and the main campus and graduate studios. Stylistically, the Commission also requested that the IMP document contain a cover page with the institution’s name and/or logo. CURRENT PROPOSAL SFAI has updated their IMP document to respond to the Commission’s comments. A cover page has been added to the document, along with additional photos of the institution throughout the IMP. Greater details regarding the student housing facilities has been provided on page 11, including the number of rooms and beds provided in each building for SFAI’s use, and the locational relationship to other campus facilities. -

Viewing This Catalog On-Line, the Easiest Way for You to Complete a Purchase Is to Click on the Item # Or First Image Associated with a Listing

(To place an online order or see enlarged or additional images, click on the inventory number or first image in any listing.) Kurt A. Sanftleben, ABAA, NSDA Read’Em Again Books Catalog 19-2a – June, 2019 41. [MARITIME] [NATIVE-AMERICANA] [WHALING] A long-lost whaling journal kept by a famous Native American whaleman that was the genesis of an important reference work on whaling music. Samuel (Sammy) G. Mingo. Whaling Bark Andrew Hicks [and the Ship California]: 1879-1883. (To place an online order or see enlarged or additional images, click on the inventory number or first image in any listing.) Our focus is on providing unusual ephemera and original personal narratives including Diaries, Journals, Correspondence, Photograph Albums, & Scrapbooks. We specialize in unique items that provide insight into American history, society, and culture while telling stories within themselves. Although we love large archives, usually our offerings are much smaller in scope; one of our regular institutional customers calls them “microhistories.” These original source materials enliven collections and provide students, faculty, and other researchers with details to invigorate otherwise dry theses, dissertations, and publications. Terms of Sale Prices are in U.S dollars. When applicable, we must charge sales tax. Unless otherwise stated, standard domestic shipping is at no charge. International shipping charges vary. All shipments are insured. If you are viewing this catalog on-line, the easiest way for you to complete a purchase is to click on the Item # or first image associated with a listing. This will open a link where you can complete your purchase using PayPal. -

Pulitzer Prize Winners and Finalists

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Networks, Stations, and Services Represented

NETWORKS, STATIONS, AND SERVICES REPRESENTED Senate Gallery 224–6421 House Gallery 225–5214 ABC NEWS—(202) 222–7700; 1717 DeSales Street, NW., Washington, DC 20036: John W. Allard, Scott Anderson, Sarah Baker, Mark Banks, Gene Barrett, Sonya Crawford Bearson, Adam Belmar, Bob Bender, Phillip M. Black, Tahman Bradley, Robert E. Bramson, Charles Breiterman, Sam Brooks, Henry M. Brown, David John G. Bull, Quiana Burns, Christopher Carlson, David Chalian, Martin J. Clancy, John Cochran, Theresa E. Cook, Richard L. Coolidge, Pam Coulter, Jan Crawford Greenburg, Max Culhane, Thomas J. d’Annibale, Jack Date, Edward Teddy Davis, Yunji Elisabeth de Nies, Clifford E. DeGray, Steven Densmore, Dominic DeSantis, Elizabeth C. Dirner, Henry Disselkamp, John F. Dittman, Peter M. Doherty, Brian Donovan, Lawrence L. Drumm, Jennifer Duck, Richard Ehrenberg, Margaret Ellerson, Daniel Glenn Elvington, Kendall A. Evans, Charles Finamore, Jon D. Garcia, Robert G. Garcia, Arthur R. Gauthier, Charles DeWolf Gibson, Thomas M. Giusto, Bernard Gmiter, Jennifer Goldberg, Stuart Gordon, Robin Gradison, Jonathan Greenberger, Stephen Hahn, Brian Robert Hartman, William T. Hatch, John Edward Hendren, Esequiel Herrera, Kylie A. Hogan, Julia Kartalia Hoppock, Matthew Alan Hosford, Amon Hotep, Bret Hovell, Matthew Jaffe, Fletcher Johnson, Kenneth Johnson, Derek Leon Johnston, Akilah N. Joseph, Steve E. Joya, James F. Kane, Jonathan Karl, David P. Kerley, John Knott, Donald Eugene Kroll, Maya C. Kulycky, Hilary Lefebvre, Melissa Anne Lopardo, Ellsworth M. Lutz, Lachlan Murdoch MacNeil, Liz Marlantes, James Martin, Jr., Luis Martinez, Darraine Maxwell, Michele Marie McDermott, Erik T. McNair, Ari Meltzer, Portia Migas, Avery Miller, Sunlen Mari Miller, Keith B. Morgan, Gary Nadler, Emily Anne Nelson, Dean E. -

Mob of 6,000 Lynches Two Hart Kh)Napers

THE WEATHER AVERAGE DAILY dROULATIOM Fereceet of 0. S. Weetht H ariford lo r the Mcmtb o f O ctober, 19SS Felr aa4 eoMer taught; iTTfWiiiig doadtaeae with 5,335 temperatnre followed b j laiB ■i—wtiiw of ttio AuAb aaow Toesdey of Clx«iiletl<»a. PRICE THREE CENTS MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, NOVEMBER 27, 1933. (FOURTEEN PAGES) VOL. Lffl., NO. 49. (Cauetfled AdvertUtny oa Page 13.) EARLE WYNEKOOP Men Lynched and Kidnap Victim MOB OF 6,000 LYNCHES INDICTMENT URGED TWO HART KH)NAPERS Chicago Officials Believe Son NINE MEET DEATH; X y Break Way Into County Ja] Had Advance Knowledge FIVE BY AUTOS Deputy Sheriff Tells Despite Barrage of Tear of His Mother’s Deed; She >4^ Details of Lynching Gas Bombs and Hang Kid Tells Abont hsorance. Week-End Toll of V iolet t V * napers in Park N earby- San Jose, Calif., Nov. 27.—(AP)<»neck and dragged him head first Deaths in Stale— Young down the steps. Caiicafo, Nov. 27.— (A P)—^Inves —Here is the story of Deputy Sher Then they went up on the third Lynching FoDows Fmfing tigators of the eerie death of Mrs. Student Killed. iff John Moore on the lynching of Hoor and found Thurmond hanging Rheta W-mekocp pressed their in John M. Holmes and ’Thomas H. by his hands to the iron grating of of Hart’ s Body San quiry for a complete solution of the " > / Thurmond, confessed kidnap-killers a high window inside the lavatory, where he thought they wouldn’t see baffling mystery today bent on an of Brooke Hart: (By Associated Press) him. -

Abstract Expressionism

Rehistoricizing the Time Around Abstract Expressionism i n t h e San Francisco Bay Area 1950s–1970s The electronic edition of this brochure is available for download as an Adobe PDF document: http://mariabonn.com/pub/electronicbrochure.pdf Acknowledgements go to Cultural Equity Grants for financial support and to the Luggage Store Gallery for aid in grant construction. Third Electronic Edition, 2006 Project Director Carlos Villa Editing & Design Maria Bonn Rehistoricizing the Time Around Abstract Expressionism in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1950s–1970s looks at this period in art history from the perspective of those who experienced it, through a series of interviews and a roundtable discussion conducted by Carlos Villa in 2005. We are documenting and archiving these conversations and making them, and the important issues that emerge, accessible for all. The material in this brochure serves as an introduction to a forthcoming printed publication. Electronic editions will be available for download through the Worlds in Collision web site http://www.usfca.edu/classes/worldsincollision/ and printed editions will be accessible from the Anne Bremer Memorial Library o f t h e San Francisco Art Institute . Our purpose is to ask what artists, issues, and historic exhibitions and publications surface when reviewing this period from a feminist and multicultural perspective. INtrodUctioN anonized art history identifies a set of “blue ribbon” artists C that have been the most studied, collected, and appreciated; these artists are, almost without exception, white and male. However, in recent decades, feminist and multicultural scholarship has identified thousands of women and persons of color that have contributed in equal measure as artists.