Putting Sodus Shaker Village on the Map

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

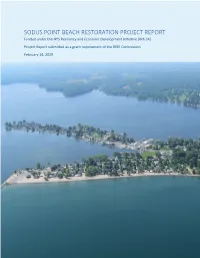

Sodus Point Beach Restoration Project Report

i | Sodus Point Beach Restoration SODUS POINT BEACH RESTORATION PROJECT REPORT Funded under the NYS Resiliency and Economic Development Initiative (WA.24) Project Report submitted as a grant requirement of the REDI Commission February 14, 2020 ii | Sodus Point Beach Restoration Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................. 1 2. PROJECT BACKGROUND AND HISTORY ..................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Location ............................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Geological Conditions ..................................................................................................................... 3 2.3 Environmental Conditions............................................................................................................... 4 2.4 Land Ownership .............................................................................................................................. 6 2.5 Present Conditions ........................................................................................................................ 10 2.6 Definition of the Problem ............................................................................................................. 16 3. PERMIT AND REGULATORY COMPLIANCE ......................................................................................... -

Federal Depository Library Directory

Federal Depositoiy Library Directory MARCH 2001 Library Programs Service Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office Wasliington, DC 20401 U.S. Government Printing Office Michael F. DIMarlo, Public Printer Superintendent of Documents Francis ]. Buclcley, Jr. Library Programs Service ^ Gil Baldwin, Director Depository Services Robin Haun-Mohamed, Chief Federal depository Library Directory Library Programs Service Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office Wasliington, DC 20401 2001 \ CONTENTS Preface iv Federal Depository Libraries by State and City 1 Maps: Federal Depository Library System 74 Regional Federal Depository Libraries 74 Regional Depositories by State and City 75 U.S. Government Printing Office Booi<stores 80 iii Keeping America Informed Federal Depository Library Program A Program of the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO) *******^******* • Federal Depository Library Program (FDLP) makes information produced by Federal Government agencies available for public access at no fee. • Access is through nearly 1,320 depository libraries located throughout the U.S. and its possessions, or, for online electronic Federal information, through GPO Access on the Litemet. * ************** Government Information at a Library Near You: The Federal Depository Library Program ^ ^ The Federal Depository Library Program (FDLP) was established by Congress to ensure that the American public has access to its Government's information (44 U.S.C. §§1901-1916). For more than 140 years, depository libraries have supported the public's right to know by collecting, organizing, preserving, and assisting users with information from the Federal Government. The Government Printing Office provides Government information products at no cost to designated depository libraries throughout the country. These depository libraries, in turn, provide local, no-fee access in an impartial environment with professional assistance. -

New York State's Public Library Systems

Facts About NEW YORK STATE’S PUBLIC LIBRARY SYSTEMS PUBLIC LIBRARY SYSTEMS • Serve over 19 million people statewide • Serve 755 public libraries with over 1,100 • Brooklyn Public Library (718) 230-2403 outlets, including over 300 neighborhood • Buffalo & Erie County Public Library (716) 858-8900 branches, 11 bookmobiles and over 100 other community outlets extending services • Chautauqua-Cattaraugus Library System (716) 484-7135 to people in correctional facilities, nursing • Clinton-Essex-Franklin Library System (5 18) 563-5190 homes, urban and rural areas • Facilitate over 15 million interlibrary loan • Finger Lakes Library System (607) 273-4074 requests annually • Four County Library System (607) 723-8236 • Provide access to e-books, NOVELNY and other electronic resources • Provide professional development and training opportunities for library staff and trustees • Operate multi-county computer networks and automated catalogs of resources • Connect with the New York State Library, school library systems, reference and research library resources councils, and school, academic and special libraries for access to specialized resources • Serve as a liaison to the New York State Library and the New York State Education Department • Mid-Hudson Library System (845) 471-6060 • Mid York Library System (315) 735-8328 THREE TYPES OF • Mohawk Valley Library System (518) 355-2010 PUBLIC LIBRARY SYSTEMS • Monroe County Library System (585) 428-8045 CONSOLIDATED: (3) Chartered as a single • Nassau Library System (516) 292-8920 entity under a board -

Research Bibliography on the Industrial History of the Hudson-Mohawk Region

Research Bibliography on the Industrial History of the Hudson-Mohawk Region by Sloane D. Bullough and John D. Bullough 1. CURRENT INDUSTRY AND TECHNOLOGY Anonymous. Watervliet Arsenal Sesquicentennial, 1813-1963: Arms for the Nation's Fighting Men. Watervliet: U.S. Army, 1963. • Describes the history and the operations of the U.S. Army's Watervliet Arsenal. Anonymous. "Energy recovery." Civil Engineering (American Society of Civil Engineers) 54 (July 1984): 60- 61. • Describes efforts of the City of Albany to recycle and burn refuse for energy use. Anonymous. "Tap Industrial Technology to Control Commercial Air Conditioning." Power 132 (May 1988): 91–92. • The heating, ventilation and air–conditioning (HVAC) system at the Empire State Plaza in Albany is described. Anonymous. "Albany Scientist Receives Patent on Oscillatory Anemometer." Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 70 (March 1989): 309. • Describes a device developed in Albany to measure wind speed. Anonymous. "Wireless Operation Launches in New York Tri- Cities." Broadcasting 116 10 (6 March 1989): 63. • Describes an effort by Capital Wireless Corporation to provide wireless premium television service in the Albany–Troy region. Anonymous. "FAA Reviews New Plan to Privatize Albany County Airport Operations." Aviation Week & Space Technology 132 (8 January 1990): 55. • Describes privatization efforts for the Albany's airport. Anonymous. "Albany International: A Century of Service." PIMA Magazine 74 (December 1992): 48. • The manufacture and preparation of paper and felt at Albany International is described. Anonymous. "Life Kills." Discover 17 (November 1996): 24- 25. • Research at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy on the human circulation system is described. Anonymous. "Monitoring and Data Collection Improved by Videographic Recorder." Water/Engineering & Management 142 (November 1995): 12. -

Great Lakes Research Consortium 2015-2017 Report 32 Years of Collaboration & Excellence in Great Lakes Science

Great Lakes Research Consortium 2015-2017 Report 32 Years of Collaboration & Excellence in Great Lakes Science www.esf.edu/glrc Great Lakes Research Consortium 2015-2017 Report 32 Years of Excellence in Working Together to Advance Great Lakes Research, Outreach & Education TABLE of CONTENTS GLRC Staff . Below Message from GLRC Director Dr. Gregory L. Boyer . 1 GLRC Member Institutions and Affiliates . 2 2015-2017 GLRC Small Grant Awards . 3 Building a Nearshore Super Model for Lake Ontario . 4 Emerging Contaminants: Unprecedented Study Defining MicroplasticsThreat to Great Lakes, Freshwaters . 5 Evaluating Vitamin B1 Deficiency in Lake Ontario Salmon . 6 GLRC Research Responds to Harmful Algal Bloom Proliferation . 7 Testing the Aquatic Research Potential of Emerging Technologies . 8 St. Lawrence River Research: Anticipating Mercury Release Impact. 9 Educating the Public about Great Lakes Science . 10 Mentoring the Next Generation of Aquatic Scientists . 11 2015-2017 GLRC Student Research Grants, Selected Publications . 12 2015-2017 GLRC Budgets . 13 Great Lakes Research Consortium (GLRC) Staff GLRC DIRECTOR GLRC ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR Dr. Gregory L. Boyer David G. White Great Lakes Research Consortium Great Lakes Research Consortium 253 Baker Lab 253 Baker Lab SUNY ESF SUNY ESF Syracuse, NY 13210 Syracuse, NY 13210 315-470-6825 • [email protected] 315-312-3042 • [email protected] ASSISTANT to the DIRECTOR RESEARCH SUPPORT SPECIALIST Theresa Baker Michael Satchwell Great Lakes Research Consortium Great Lakes Research Consortium 253 Baker Lab 253 Baker Lab SUNY ESF SUNY ESF Syracuse, NY 13210 Syracuse, NY 13210 315-470-6720 • [email protected] 315-470-4864 • [email protected] Advancing Great Lakes Science A message from Great Lakes Research Consortium Director Dr. -

Port Bay Wayne County, New York Joseph C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The College at Brockport, State University of New York: Digital Commons @Brockport The College at Brockport: State University of New York Digital Commons @Brockport Studies on Water Resources of New York State and Technical Reports the Great Lakes 1-2010 Port Bay Wayne County, New York Joseph C. Makarewicz The College at Brockport, [email protected] Matthew .J Nowak The College at Brockport Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/tech_rep Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Repository Citation Makarewicz, Joseph C. and Nowak, Matthew J., "Port Bay Wayne County, New York" (2010). Technical Reports. 43. http://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/tech_rep/43 This Technical Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Studies on Water Resources of New York State and the Great Lakes at Digital Commons @Brockport. It has been accepted for inclusion in Technical Reports by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @Brockport. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Port Bay Wayne County, New York Joseph C. Makarewicz and Matthew J. Nowak The College at Brockport, State University of New York January 2010 Located midway between Rochester and Oswego, New York, Port Bay is one of southern Lake Ontario’s larger but relatively shallow (<25 feet) embayments. The perimeter of the bay is primarily residential, but portions of the shoreline and watershed are part of the Lake Shores Marshes Wildlife Area. Wolcott Creek is the major tributary of Port Bay and drains ~27 mi2 of land that is mostly in agriculture. -

Holly Henley, Library Develo

New York State Library Early Literacy Training—State Library Research and Best Practices Arizona: Holly Henley, Library Development Director, Arizona State Library, Archives and Public Records, A Division of the Secretary of State, Carnegie Center, 1101 West Washington, Phoenix, AZ 85007, Phone: 602-926-3366, Fax: 602-256-7995, E-mail: [email protected] Insights: Library staff members who plan to offer early literacy workshops for parents and caregivers find it very helpful to see a demonstration of Every Child Ready to Read and Brain Time before doing them on their own. They also find it helpful to have someone who can act as a mentor while they are getting started. On an ongoing basis, a vehicle for communication and sharing experiences between those who are doing early literacy outreach is very helpful. It is essential to provide ongoing training opportunities for library staff in order to train new staff members in libraries and to keep continuing staff members informed of the latest best practices. Project Description Partnerships and Funding Training and Technology Evaluation Building a New Generation of Readers: A statewide early literacy Trainings and resources for early Face-to-face trainings with Saroj Rhian Evans Allvin and the Brecon project designed by the State Library that provides public and school literacy are supported with LSTA Ghoting, Betsy Diamant-Cohen, Group prepared an evaluation of librarians with the training and materials to teach parents and childcare funding from IMLS, administered Elaine Meyers and staff from New early literacy work by the State providers strategies for preparing children to enter school ready to learn by the Arizona State Library. -

Survey the Library Resources in the Eight Mid-Hudson Counties of Columbia

DOCIMENT RESLME ED 032 889 LI 001 311 By -Reichmann, Felix; And Others Library Resources in the Mid-Hudson Valley: Columbia, Dutchess, Greene, Orange, Putnam. Rockland. Sullivan, Ulster. Spons Agency-Mid-Hudson Libraries. Poughkeepsie. N.Y.; Ramapo Catskill Library System. Middletown. N.Y. Pub Date 65 Note -519p. EDRS Price MF -$2.00 HC -$26.05 Descriptors -Centralization. College Libraries. *Library Cooperation. sr-ibrary Networks. *Library Planning. Library Services, *Library Surveys, Public Libraries. School Libraries. Special Libraries Identifiers-New York The purpose of this study was to "survey the library resources in the eight Mid-Hudson Counties of Columbia. Dutchess. Greene. Orange, Putnam. Rockland. Sullivan. and Ulster in order to develop a plan of service in which assets would be shared. resources developed, and services extended." Survey data were collected by six questionnaires; visits and evaluations of college, public and special libraries; and a review of the literature of the field. Study findings are presented in sections on the history of the region, the present situation. and libraries of all types. A summary and projections are also included. Thirty-five specific recommendations are made which cover overall planning. public libraries. college libraries. school libraries. central services, and future development. The basic recommendation of the study is that the eight counties of the Hudson Valley be considered as a unified library area, with the Southeastern New York Library Resources Council designated as theagency to work toward integration of alllibraries at alllevels in the eight counties. Appendixes include tables of survey data. the survey questionnaires. and checklists used in the library evaluations. -

Village of Sodus Point Local Waterfront Revitalization Program

Village of Sodus Point Local Waterfront Revitalization Program Adopted: Village Board, June 5, 2006 Approved: Acting NYS Secretary of State Frank P. Milano, December 28, 2006 Concurred: U.S. Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, April 17, 2008 This Local Waterfront Revitalization Program (LWRP) has been adopted and approved in accordance with provisions of the Waterfront Revitalization of Coastal Areas and Inland Waterways Act (Executive Law, Article 42) and its implementing regulations (6 NYCRR 601). Federal concurrence on the incorporation of this Local Waterfront Revitalization Program into the New York State Coastal Management Program as a routine program change has been obtained in accordance with provisions of the U.S. Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972 (P.L. 92-583), as amended, and its implementing regulations (15 CFR 923). The preparation of this program was financially aided by a federal grant from the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended. Federal Grant No. NA-82-AA-D-CZ068. The New York State Coastal Management Program and the preparation of Local Waterfront Revitalization Programs are administered by the New York State Department of State, Division of Coastal Resources, One Commerce Plaza, 99Washington Avenue, Albany, New York 12231. STATE OF NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF STATE 41 STATE STREET ALBANY, NY 12231-0001 George E. Pataki Christopher L. Jacobs Governor Secretary of State December 28, 2006 Honorable Michael Sullivan Mayor Village of Sodus Point 8356 Bay Street PO box 159 Sodus Point, NY 14555 Deay Mayor Sullivan: I am pleased to inform you that I have approved the Village of Sodus Point Local Waterfront Revitalization Program (LWRP), pursuant to the Waterfront Revitalization of Coastal Areas and Inland Waterways Act. -

Handbook for Library Trustees of New York State; 2018 Edition

2018 HANDBOOK FOR Edition LIBRARY TRUSTEES OF NEW YORK STATE Jerry Nichols, Palmer School of Library and Information Science, LIU Post, Brookville, NY Rebekkah Smith Aldrich, Mid -Hudson Library System, Poughkeepsie, NY With the assistance of the Library Trustees Association of New York State New York Library Association New York State Library Public Library Systems Directors Organization of New York State © 2018 Portions of this publication may be reproduced for noncommercial purposes provided attribution of source is included Printed by the Suffolk Cooperative Library System Bellport, New York Handbook for Library Trustees 2018 Edition HANDBOOK FOR LIBRARY TRUSTEES OF NEW YORK STATE 2018 Edition Jerry Nichols, Palmer School of Library and Information Science; LIU Post, Brookville, NY Rebekkah Smith Aldrich, Mid-Hudson Library System, Poughkeepsie, NY With the assistance of the Library Trustees Association of New York State New York Library Association New York State Library Public Library System Directors Organization of New York State © 2018 Portions of this publication may be reproduced for noncommercial purposes provided attribution of source is included Handbook for Library Trustees 2018 Edition ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This latest revision of the Handbook for Library Trustees of New York State is a testament to the integrity, professionalism and commitment of the New York Library Community. A network of library professionals, directors, trustees and association leaders, along with our colleagues at the New York State Library, continuously strive to provide the best possible library service to the people of New York and inspire us to ensure there is clear, accurate and concise support for the 6,000 New Yorkers who serve their communities as library trustees each year. -

Handbook for Library Trustees of New York State

Handbook for Library Trustees of New York State 2010 Edition Jerry Nichols Palmer School of Library and Information Science Long Island University, Brookville, New York With the assistance of the Public Library System Directors Organization of New York State Library Trustees Association of New York State Division of Library Development, New York State Library © 2010 Portions of this publication may be reproduced for noncommercial purposes provided attribution of source is included. Handbook for Library Trustees_______________________________________2010 Edition ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This latest revision of the Handbook for Library Trustees of New York State is a continuation of a decades long effort to provide library trustees with a readable and concise reference to assist them in the performance of their duties. In this edition we have strengthened those areas of the Handbook that generated the most interest since the 2005 edition. The assistance of the following groups and individuals in the development of this Handbook is gratefully acknowledged: the Public Library System Directors of New York State, especially Jennifer Morris of the Pioneer Library System, Valerie Lewis and Kevin Verbesey of the Suffolk Cooperative System; the Board of Directors of the Library Trustees Association of New York State, in particular Mary Ellen O’Connor; Bernard Margolis, State Librarian and Carol Desch, Director of the Division of Library Development, with a particular note of appreciation to Maria Hazapis, Joseph J. Mattie and Lisa Seivert of their staff. Special thanks to Kevin Seaman, Esq. and Albert Coster, CPA for their advice in legal and accounting matters. Their support, encouragement, helpful suggestions, critical and inquiring minds have all helped to shape, mold, and improve this Handbook. -

Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletins the Roosevelt Wild Life Station

SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Digital Commons @ ESF Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletins The Roosevelt Wild Life Station 1939 Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin Ralph T. King SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/rwlsbulletin Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation King, Ralph T., "Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin" (1939). Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletins. 10. https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/rwlsbulletin/10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The Roosevelt Wild Life Station at Digital Commons @ ESF. It has been accepted for inclusion in Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletins by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ESF. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Bulletin of the New York State Vol. XII. No. 2 College of Forestry at Syracuse University October, 1939 THE ECOLOGY AND ECONOMICS OF THE BIRDS ALONG THE NORTHERN BOUNDARY OF NEW YORK STATE By A. Sidney Hyde Roosevelt Wildlife Bulletin VOLUME 7 NUMBER 2 Published by the Roosevelt Wildlife Forest Experiment Station at the New York State College of Forestry, Syracuse, N. Y. SAMUEL N. SPRING. Dean . CONTENTS OF RECENT ROOSEVELT WIUDLIFE BULLETINS AND ANNALS BULLETINS Roosevelt Wildlife Bulletin, Vol. 4, No. i. October, 1926. 1. The Relation of Birds to Woodlots in New York State Waldo L. McAtee 2. Current Station Notes Charles C. Adams (Out of print) Roosevelt Wildlife Bulletin, Vol. 4, No. 2. June, 1927. 1. The Predatory and Fur-bearing Animals of the Yellowstone National Park Milton P.