Sand Whiting (2016)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparisons Between the Biology of Two Species of Whiting (Sillaginidiae) in Shark Bay, Western Australia

Comparisons between the biology of two species of whiting (Sillaginidiae) in Shark Bay, Western Australia By Peter Coulson Submitted for the Honours Degree of Murdoch University August 2003 1 Abstract Golden-lined whiting Sillago analis and yellow-fin whiting Sillago schomburgkii were collected from waters within Shark Bay, which is located at ca 26ºS on the west coast of Australia. The number of circuli on the scales of S. analis was often less than the number of opaque zones in sectioned otoliths of the same fish. Furthermore, the number of annuli visible in whole otoliths of S. analis was often less than were detectable in those otoliths after sectioning. The magnitude of the discrepancies increased as the number of opaque zones increased. Consequently, the otoliths of S. analis were sectioned in order to obtain reliable estimates of age. The mean monthly marginal increments on sectioned otoliths of S. analis and S. schomburgkii underwent a pronounced decline in late spring/early summer and then rose progressively during summer and autumn. Since these trends demonstrated that opaque zones are laid down annually in the otoliths of S. analis and S. schomburgkii from Shark Bay, their numbers could be used to help age this species in this marine embayment. The von Bertalanffy growth parameters, L∞, k and to derived from the total lengths at age for individuals of S. analis , were 277 mm, 0.73 year -1 and 0.02 years, respectively, for females and 253 mm, 0.76 year -1 and 0.10 years, respectively. Females were estimated to attain lengths of 141, 211, 245 and 269 mm after 1, 2, 3 and 5 years, compared with 124, 192, 224 and 247 mm for males at the corresponding ages. -

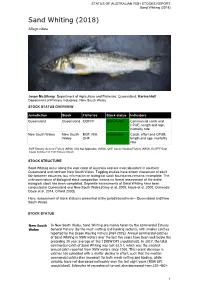

SAFS Report 2018

STATUS OF AUSTRALIAN FISH STOCKS REPORT Sand Whiting (2018) Sand Whiting (2018) Sillago ciliata Jason McGilvray: Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Queensland, Karina Hall: Department of Primary Industries, New South Wales STOCK STATUS OVERVIEW Jurisdiction Stock Fisheries Stock status Indicators Queensland Queensland ECIFFF Sustainable Commercial catch and CPUE, length and age, mortality rate New South Wales New South EGF, N/A, Sustainable Catch, effort and CPUE, Wales OHF length and age, mortality rate EGF Estuary General Fishery (NSW), N/A Not Applicable (NSW), OHF Ocean Hauling Fishery (NSW), ECIFFF East Coast Inshore Fin Fish Fishery (QLD) STOCK STRUCTURE Sand Whiting occur along the east coast of Australia and are most abundant in southern Queensland and northern New South Wales. Tagging studies have shown movement of adult fish between estuaries, but information on biological stock boundaries remains incomplete. The unknown nature of biological stock composition means no formal assessment of the entire biological stock has been completed. Separate assessments of Sand Whiting have been conducted in Queensland and New South Wales [Gray et al. 2000, Hoyle et al. 2000, Ochwada- Doyle et al. 2014, O’Neill 2000]. Here, assessment of stock status is presented at the jurisdictional level—Queensland and New South Wales. STOCK STATUS New South In New South Wales, Sand Whiting are mainly taken by the commercial Estuary Wales General Fishery (by the mesh netting and hauling sectors), with smaller catches reported by the Ocean Hauling Fishery [Hall 2015]. Annual commercial catches of Sand Whiting in NSW waters over the last five years have been well below the preceding 20 year average of 162 t [NSW DPI unpublished]. -

Catalogue of Protozoan Parasites Recorded in Australia Peter J. O

1 CATALOGUE OF PROTOZOAN PARASITES RECORDED IN AUSTRALIA PETER J. O’DONOGHUE & ROBERT D. ADLARD O’Donoghue, P.J. & Adlard, R.D. 2000 02 29: Catalogue of protozoan parasites recorded in Australia. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 45(1):1-164. Brisbane. ISSN 0079-8835. Published reports of protozoan species from Australian animals have been compiled into a host- parasite checklist, a parasite-host checklist and a cross-referenced bibliography. Protozoa listed include parasites, commensals and symbionts but free-living species have been excluded. Over 590 protozoan species are listed including amoebae, flagellates, ciliates and ‘sporozoa’ (the latter comprising apicomplexans, microsporans, myxozoans, haplosporidians and paramyxeans). Organisms are recorded in association with some 520 hosts including mammals, marsupials, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish and invertebrates. Information has been abstracted from over 1,270 scientific publications predating 1999 and all records include taxonomic authorities, synonyms, common names, sites of infection within hosts and geographic locations. Protozoa, parasite checklist, host checklist, bibliography, Australia. Peter J. O’Donoghue, Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, The University of Queensland, St Lucia 4072, Australia; Robert D. Adlard, Protozoa Section, Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia; 31 January 2000. CONTENTS the literature for reports relevant to contemporary studies. Such problems could be avoided if all previous HOST-PARASITE CHECKLIST 5 records were consolidated into a single database. Most Mammals 5 researchers currently avail themselves of various Reptiles 21 electronic database and abstracting services but none Amphibians 26 include literature published earlier than 1985 and not all Birds 34 journal titles are covered in their databases. Fish 44 Invertebrates 54 Several catalogues of parasites in Australian PARASITE-HOST CHECKLIST 63 hosts have previously been published. -

New Distributional Record of the Endemic Estuarine Sand Whiting, Sillago Vincenti Mckay, 1980 from the Pichavaram Mangrove Ecosystem, Southeast Coast of India

Indian Journal of Geo Marine Sciences Vol. 47 (03), March 2018, pp. 660-664 New distributional record of the endemic estuarine sand whiting, Sillago vincenti McKay, 1980 from the Pichavaram mangrove ecosystem, southeast coast of India Mahesh. R1δ, Murugan. A2, Saravanakumar. A1*, Feroz Khan. K1 & Shanker. S1 1CAS in Marine Biology, Faculty of Marine Sciences, Annamalai University, Porto Novo, Tamil Nadu, India - 608 502. 2Department of Value Added Aquaculture (B.Voc.), Vivekananda College, Agasteeswaram, India - 629 701. δ Present Address: National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management, MoEF & CC, Chennai, India - 600 025. *[E-mail: [email protected]] Received 27 December 2013 ; revised 17 November 2016 The Sillaginids, commonly known as sand whiting are one among the common fishes caught by the traditional fishers in estuarine ecosystems all along the Tamil Nadu coast. The present study records the new distributional range extension for Sillago vincenti from the waters of Pichavaram mangrove, whereas earlier reports were restricted to only the Palk Bay and Gulf of Mannar regions of the Tamil Nadu coast, whereas it enjoys a wide range of distribution both in the east and west coast of India. This study marks the additional extension of the distributional record for S. vincenti in the east coast of India. Biological information on these fishes will have ecological applications particularly on account on their extreme abundance in the mangrove waters. The present study is based on the collection of specimens from handline fishing practices undertaken in the shallow waters of Pichavaram mangroves, on the southeast coast of India. [Keywords: Sillagnids, Sillago vincenti, Pichavaram, India] Introduction Sillaginopodys and Sillaginops)8. -

Stock Assessments of Bream, Whiting and Flathead (Acanthopagrus Australis, Sillago Ciliata and Platycephalus Fuscus) in South East Queensland

Department of Agriculture and Fisheries Stock assessments of bream, whiting and flathead (Acanthopagrus australis, Sillago ciliata and Platycephalus fuscus) in South East Queensland April 2019 This publication has been compiled by George M. Leigh1, Wen-Hsi Yang2, Michael F. O’Neill3, Jason G. McGilvray4 and Joanne Wortmann3 for the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries. It provides assessments of the status of south east Queensland’s populations of yellowfin bream, sand whiting and dusky flathead, three of Australia’s most commonly fished species. 1Agri-Science Queensland, Floor 5, 41 George Street, Brisbane, Queensland 4000, Australia 2Centre for Applications in Natural Resource Mathematics (CARM), School of Mathematics and Physics, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, Queensland 4072, Australia 3Agri-Science Queensland, Maroochy Research Facility, 47 Mayers Road, Nambour, Queensland 4560, Australia 4Fisheries Queensland, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Level 1A East, Ecosciences Precinct, 41 Boggo Rd, Dutton Park, Queensland 4102, Australia © The State of Queensland, 2019 Cover photos: Yellowfin bream Acanthopagrus australis, sand whiting Sillago ciliata and dusky flathead Platycephalus fuscus (source: John Turnbull, Creative Commons by Attribution, Non-commercial, Share-alike licence). The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons by Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. -

Description of Key Species Groups in the East Marine Region

Australian Museum Description of Key Species Groups in the East Marine Region Final Report – September 2007 1 Table of Contents Acronyms........................................................................................................................................ 3 List of Images ................................................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................... 5 1 Introduction............................................................................................................................ 6 2 Corals (Scleractinia)............................................................................................................ 12 3 Crustacea ............................................................................................................................. 24 4 Demersal Teleost Fish ........................................................................................................ 54 5 Echinodermata..................................................................................................................... 66 6 Marine Snakes ..................................................................................................................... 80 7 Marine Turtles...................................................................................................................... 95 8 Molluscs ............................................................................................................................ -

Population Parameters of Indian Sand Whiting Sillago Sihama (Forsskal) from Estuaries of Southern Karnataka

J. mar. biol. Ass. India, 2003, 45 (1) : 54 - 60 Population parameters of Indian sand whiting Sillago sihama (Forsskal) from estuaries of southern Karnataka. K.S. Udupa, C.H. Raghavendra, Vinayak Bevinahalli, G. R. Aswatha Reddy and M. Averel College of Fisheries, Kankanady, Mangalore - 575 002, India Abstract The Indian sand whiting, Sillago sihama, occurring in the estuaries of Karnataka along the southwest coast of India was found to attain a mean length of 17.1,25.2,29.2 and 31.1 cm at the end of 1-4 years respectively. From the length-converted catch curve, the total fishing mor- tality Z was estimated as 3.79 year-' whereas from Jones and van Zalinge method Z was esti- mated to be 3.28. The natural mortality M was estimated to be 1.41 which gave F = 2.38. The exploitation rate E = 0.63 gave an indication that S. sihama fishery is facing moderately higher fishing pressure in these estuaries. lc was estimated as 14.45 cm, Im=16.5cm and lopt=20.7cm. The length-weight'relationship was found to be W = 0.02471 L 2.56. Wmwas estimated as 197g. The life span of the species is around 4.22 years. A note on the spawning season and recruit- ment pattern is also included in this paper. Introduction some of them are commercially important. Even though many studies have been An attempt is made in this paper to esti- conducted on the stock assessment of mate the population parameters and to marine fishes from India, very few attempts study the spawning season of Indian sand have been made on the stock assessment whiting S. -

Recreational Fishing Identification Guide

Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Recreational fishing identification guide June 2020 Contents About this guide.................................................................................................. 1 Offshore demersal .............................................................................................. 3 Inshore demersal ................................................................................................ 4 Nearshore .........................................................................................................12 Estuarine ..........................................................................................................19 Pelagic ..............................................................................................................20 Sharks ..............................................................................................................23 Crustaceans .....................................................................................................25 Molluscs............................................................................................................27 Freshwater........................................................................................................28 Cover: West Australian dhufish Glaucosoma hebraicum. Photo: Mervi Kangas. Published by Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Perth, Western Australia. Fisheries Occasional Publication No. 103, sixth edition, June 2020. ISSN: 1447 – 2058 (Print) -

A Contribution to the Biology of Indian Sand V7hiting-Sillag0 Sihama (Forskal)

A CONTRIBUTION TO THE BIOLOGY OF INDIAN SAND V7HITING-SILLAG0 SIHAMA (FORSKAL) BY N. RADHAKRISHNAN* [Central Marine Fisheries Research Station, Mandapam Camp (S. Rly.)] CONTENTS PAGE I. INTRODUCTION .. .. .. .. 254 II. MATERIAL AND METHODS .. .. 255 in. DISTRIBUTION .. .. .. .. 255 IV. RELATIONSHIP OF BODY MEASUREMENTS TO TOTAL LENGTH .. .. .. 256 V. WEIGHT-LENGTH RELATIONSHIP .. .. 258 VI. PONDERAL INDEX OR CONDITION FACTOR .. 261 VII. FOOD AND FEEDING HABITS .. .. 262 VIII. MATURATION AND SPAWNING .. .. 266 TX. SEX RATIO AND FECUNDITY .. .. 270 X. AGE AND RATE OF GROWTH .. .. 272 XI. FISHERY AND FISHING METHODS .. .. 279 XII. SUMMARY .. .. .. .. 280 XIII. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .. .. .. 281 XIV. REFERENCES .. .. .. ..281 INTRODUCTION THE Indian Sand Whiting, belonging to the family Uaginidae (Order Percomorphoidea), is of some importance to the coastal and estuarine fisheries of India. Very little detailed study of this fish seems to have been made, except for a short account of its food and feeding habits by Chacko (1949), notes on the larval and post-larval stages by Gopinath (1942, 1946), general notes by Devanesan and Chidambaram (1948), and observations on the eggs and larvae by Chacko (1950). Cleland (1947) has given an account of the * Present address: Central Marine Fisheries Researcli Unit, Karwar. 254 Contribution to Biology of Indian Sand Whiting 255 economic biology of the Sand Whiting, Sillago ciliata, the best known species in Australian waters. The post-larval stages of this species were described by Munro (1945) and eggs and early larvae by Tosh (1903). Although there are three Indian species, Sillago sihama, Sillago panijus and Sillago maculata, the first constitutes by far the largest element in the commercial catches around Mandapam and Rameswaram Island in the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay. -

Fao Species Catalogue

FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 125, Volume 14 ISSN 0014-5602 FIR/S 125 Vol. 14 FAO SPECIES CATALOGUE VOL. 14 SILLAGINID FISHES OF THE WORLD (Family Sillaginidae) An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of the Sillago, Smelt or Indo-Pacific Whiting Species Known to Date FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 125, Volume 14 FIR/S125 Vol. 14 FAO SPECIES CATALOGUE VOL. 14. SILLAGINID FISHES OF THE WORLD (Family Sillaginidae) An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of the Sillago, Smelt or Indo-Pacific Whiting Species Known to Date by Roland J. McKay Queensland Museum P.O. Box 3300, South Brisbane Australia, 4101 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 1992 The designations employed and the presenta- tion of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-40 ISBN 92-5-103123-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior per- mission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Publications Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Via delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. © FAO Rome 1992 ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ iii PREPARATION OF THIS DOCUMENT This document was prepared under the FAO Fisheries Department Regular Programme in the Marine Resources Service of the Fishery Resources and Enivornment Division. -

Sillago Sihama) in the South Coastal of Iran (Persian Gulf and Oman Sea)

Available online a t www.scholarsresearchlibrary.com Scholars Research Library Annals of Biological Research, 2013, 4 (5):269-278 (http://scholarsresearchlibrary.com/archive.html) ISSN 0976-1233 CODEN (USA): ABRNBW Reproduction characteristics and length- weight relationships of the sand whiting (Sillago sihama) in the south coastal of Iran (Persian Gulf and Oman Sea) Mohammad Reza Mirzaei 1, Tooraj Valinasab 2, Zulfigar Yasin 1 and Aileen Tan Shau Hwai 1 1School of Biological Sciences, University Sains Malaysia, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia 2Iranian Fisheries Research Organization (IFRO), Tehran, Iran _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Sillago sihama is one of the most common recreational and commercial species in the local fishery in the Persian Gulf and Oman Sea. Various aspects of the reproductive biology of the S. sihama are studied to describe gonad development, spawning season, sex ratio, ovarian histology and fecundity. A total of 676 fish with a total length of 10.44-25.4 cm (Males), 11.17-24.8 cm (Females) and the total body weight ranged between 11.86-124.53 g (males) and 13.96-114.05 g (females) were used for this study. Sex ratio defined as the proportion of females to males was 1.2:1; microscopic and macroscopic gonad analysis and monthly variation of GSI in female component of the S. sihama shows a reproductive season from April and May and continued until June. The ova diameter frequency distributions in mature component indicated that the species exhibits a synchronous-group and monocyclic ovary characterized by deposition in a single batch of eggs per year (total spawner). The size at which 50% of the population attain sexual maturity (Lm50) is 138 mm for females and 132 mm for males. -

LOCAL FISHING GUIDE: Townsite TANKER JETTY FISHING Species: Herring, Skippy, Squid

LOCAL FISHING GUIDE: Townsite TANKER JETTY FISHING Species: herring, skippy, squid. Fishing rig: Use a light line (max 12lb breaking strain). Small hook (5/8) and light sinker, just sufficient to ensure that the wind does not blow the line out of the water. Skippy feed deeper than herring so a heavier sinker can be used for them. Bait: squid, mince or river prawns. Use berley/pollard. East of Esperance WHYLIE BAY, ROSSITER TO STOCKYARD CREEK 4WD ONLY. Species: Salmon, skippy, herring, sand whiting, salmon trout, flathead, gummy shark. CAPE LE GRAND, HELLFIRE BAY, THISTLE COVE, LUCKY BAY & ROSSITER Access to all areas by car. All places within the national park. Species: Salmon, skippy, herring, sand whiting, salmon trout, flathead, gummy shark, snook, gardie, groper. DUNNS ROCK & VICTORIA HARBOUR Species: Salmon, skippy, herring, sand whiting, salmon trout, flathead, gummy shark, shark, rock varieties around headlands. WHARTON BEACH Accessible by car. 4WD beach areas. Species: salmon, skippy, herring, salmon trout, flathead, gummy shark. Rock varieties around headlands and yellow eyed mullet in small bays. DUKE OF ORLEANS BAY Accessible by car. Picnic area provided. Narrow strip of land leads to an island where most fishing is done. Species: herring, skippy, snook, gardie, flathead, sand whiting, groper and rock varieties. MEMBINUP Accessible by car at most times. 4WD beach area. Species: salmon, skippy, herring, salmon trout, flathead, gummy shark. Rock varieties are found around headland. ALEXANDER BAY Predominantly 4WD. Species: salmon, skippy, herring, salmon trout, sand whiting, king George whiting, gummy shark & rock varieties. BLACKBOY CREEK & TAGON HARBOUR Access to Thomas River by car.