Introduction: Notes on Almost Nothing 1 H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

Seagram Building, First Floor Interior

I.andmarks Preservation Commission october 3, 1989; Designation List 221 IP-1665 SEAGRAM BUIIDING, FIRST FLOOR INTERIOR consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; 375 Park Avenue, Manhattan. Designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with Philip Johnson; Kahn & Jacobs, associate architects. Built 1956-58. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1307, Lot 1. On May 17, 1988, the landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Seagram Building, first floor interior, consisting of the lobby and passenger elevator cabs and the fixtures and interior components of these spaces including but not limited to, interior piers, wall surfaces, ceiling surfaces, floor surfaces, doors, railings, elevator doors, elevator indicators, and signs; and the proposed designation of the related I.and.mark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Twenty witnesses, including a representative of the building's owner, spoke in favor of designation. No witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters in favor of designation. DFSCRIPI'ION AND ANALYSIS Summary The Seagram Building, erected in 1956-58, is the only building in New York City designed by architectural master Iudwig Mies van der Rohe. Constructed on Park Avenue at a time when it was changing from an exclusive residential thoroughfare to a prestigious business address, the Seagram Building embodies the quest of a successful corporation to establish further its public image through architectural patronage. -

EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture / Mies Van Der Rohe Award: a Tribute to Bauhaus

AT A GLANCE EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture / Mies van der Rohe Award: A tribute to Bauhaus The EU Prize for Contemporary Architecture (also known as the EU Mies Award) was launched in recognition of the importance and quality of European architecture. Named after German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, a figure emblematic of the Bauhaus movement, it aims to promote functionality, simplicity, sustainability and social vision in urban construction. Background Mies van der Rohe was the last director of the Bauhaus school. The official lifespan of the Bauhaus movement in Germany was only fourteen years. It was founded in 1919 as an educational project devoted to all art forms. By 1933, when the Nazi authorities closed the school, it had changed location and director three times. Artists who left continued the work begun in Germany wherever they settled. Recognition by Unesco The Bauhaus movement has influenced architecture all over the world. Unesco has recognised the value of its ideas of sober design, functionalism and social reform as embodied in the original buildings, putting some of the movement's achievements on the World Heritage List. The original buildings located in Weimar (the Former Art School, the Applied Art School and the Haus Am Horn) and Dessau (the Bauhaus Building and the group of seven Masters' Houses) have featured on the list since 1996. Other buildings were added in 2017. The list also comprises the White City of Tel-Aviv. German-Jewish architects fleeing Nazism designed many of its buildings, applying the principles of modernist urban design initiated by Bauhaus. -

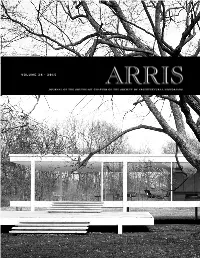

Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M

VOLUME 26 · 2015 JOURNAL OF THE SOUTHEAST CHAPTER OF THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS Volume 26 · 2015 1 Editors’ Note Articles 6 Madness and Method in the Junkerhaus: The Creation and Reception of a Singular Residence in Modern Germany MIKESCH MUECKE AND NATHANIEL ROBERT WALKER 22 Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M. DRELLER 40 The “Monster Problem”: Texas Architects Try to Keep it Cool Before Air Conditioning BETSY FREDERICK-ROTHWELL 54 Electrifying Entertainment: Social and Urban Modernization through Electricity in Savannah, Georgia JESSICA ARCHER Book Reviews 66 Cathleen Cummings, Decoding a Hindu Temple: Royalty and Religion in the Iconographic Program of the Virupaksha Temple, Pattadakal REVIEWED BY DAVID EFURD 68 Reiko Hillyer, Designing Dixie: Tourism, Memory, and Urban Space in the New South REVIEWED BY BARRY L. STIEFEL 70 Luis E, Carranza and Fernando L. Lara, Modern Architecture in Latin America: Art, Technology, and Utopia REVIEWED BY RAFAEL LONGORIA Field Notes 72 Preserving and Researching Modern Architecture Outside of the Canon: A View from the Field LYDIA MATTICE BRANDT 76 About SESAH ABSTRACTS Sarah M. Dreller Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency Abstract This paper studies the creation, circulation, and reception of two groups of photographs of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s iconic Farnsworth House, both taken by Hedrich Blessing. The first set, produced for a 1951 Architectural Forum magazine cover story, features curtains carefully arranged according to the architect’s preferences; the Museum of Modern Art commis- sioned the second set in 1985 for a major Mies retrospective exhibition specifically because the show’s influential curator, Arthur Drexler, believed the curtains obscured Mies’ so-called “glass box” design. -

Modernism's Influence on Architect-Client Relationship

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Architectural and Environmental Engineering Vol:12, No:10, 2018 Modernism’s Influence on Architect-Client Relationship: Comparative Case Studies of Schroder and Farnsworth Houses Omneya Messallam, Sara S. Fouad beliefs in accordance with modern ideas, in the late 19th and Abstract—The Modernist Movement initially flourished in early 20th centuries. Additionally, [2] explained it as France, Holland, Germany and the Soviet Union. Many architects and specialized ideas and methods of modern art, especially in the designers were inspired and followed its principles. Two of its most simple design of buildings of the 1940s, 50s and 60s which important architects (Gerrit Rietveld and Ludwig Mies van de Rohe) were made of modern materials. On the other hand, [3] stated were introduced in this paper. Each did not follow the other’s principles and had their own particular rules; however, they shared that, it has meant so much that it has often meant nothing. the same features of the Modernist International Style, such as Anti- Perhaps, the belief of [3] stemmed from a misunderstanding of historicism, Abstraction, Technology, Function and Internationalism/ the definitions of Modernism, or what might be true is that it Universality. Key Modernist principles translated into high does not have a clear meaning to be understood. Although this expectations, which sometimes did not meet the inhabitants’ movement was first established in Europe and America, it has aspirations of living comfortably; consequently, leading to a conflict become global. Applying Modernist principles on residential and misunderstanding between the designer and their clients’ needs. -

Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe: Technology and Architecture

1950 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: Technology and architecture In 1932 Mies moved to Berlin with the teachers and students ofthe Bauhaus and there continued it as a private institute. In July 1933 it was closed by the Gestapo. In summer 1937 Mieswent tathe USA; in 1938 he received an invitation to the Illinois Institute ofTechnology (liT) in Chicago and a little later was commissioned to redesign the university campus. The first buildings went up in the years 1942-3. They introduced the second great phase ofhis architecture. In 1950 Mies delivered to the liT the speech reproduced here. Technology is rooted in the past. It dominates the present and tends into the future. It is a real historical movement - one of the great movements which shape and represent their epoch. It can be compared only with the Classic discovery of man as a person, the Roman will to power, and the religious movement ofthe Middle Ages. Technology is far more than a method, it is a world in itself. As a method it is superior in almost every respect. But only where it is left to itself, as in gigantic structures of engineering, there tech nology reveals its true nature. There it is evident that it is not only a useful means, but that it is something, something in itself, something that has a meaning and a powerful form - so powerful in fact, that it is not easy to name it. Is that still technology or is it architecture? And that may be the reason why some people are convinced that architecture will be outmoded and replaced by technology. -

Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe. American, Born Germany

LESSON FOUR: Exploring the Design Process 17 L E S S O IMAGE TWELVE: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. IMAGE THIRTEEN: Ludwig Mies van der N American, born Germany. 1886–1969. Rohe. American, born Germany. 1886–1969. S Seagram Building, New York. 1954–58. Seagram Building, New York. 1954–58. Site View of north side. Photo: Hedrich Blessing. and floor plans. Ink on illustration board, 1 The Museum of Modern Art, New York 27 ⁄2 x 20" (69.9 x 50.8 cm). The Mies van der Rohe Archive IMAGE FOURTEEN: Ludwig Mies van der IMAGE FIFTEEN: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Rohe. American, born Germany. 1886–1969. American, born Germany. 1886–1969. Seagram Building, New York. 1954–58. Seagram Building, New York. 1954–58. North and west elevations. Pencil on ozalid, Model, aerial view of plaza and lower floors. 1 37 ⁄4" x 52" (94.6 x 132.1 cm). Revised Photo: Louis Checkman. The Museum of February 18, 1957. The Mies van der Rohe Modern Art, New York Archive IMAGE SIXTEEN: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. IMAGE SEVENTEEN: Ludwig Mies van der American, born Germany. 1886–1969. Rohe. American, born Germany. 1886–1969. Seagram Building, New York. 1954–58. Seagram Building, New York. 1954–58. Construction photograph showing steel View, office interior. Photo: Ezra Stoller. frame. Photo: House of Patria. The Mies van Esto Photographics der Rohe Archive. Gift of the architect IMAGE EIGHTEEN: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. American, born Germany. 1886–1969. Brno Chair. 1929–30. Chrome-plated steel and 1 leather, 31 ⁄2 x 23 x 24" (80 x 58.4 x 61 cm). -

Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe's Richard King Mellon Hall of Science and Michael Graves's Erickson Alumni Center

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 Classicism as Foundation in Architecture: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Richard King Mellon Hall of Science and Michael Graves's Erickson Alumni Center Elizabeth Stoloff Vehse West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Vehse, Elizabeth Stoloff, "Classicism as Foundation in Architecture: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Richard King Mellon Hall of Science and Michael Graves's Erickson Alumni Center" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 848. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/848 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Classicism as Foundation in Architecture: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Richard King Mellon Hall of Science and Michael Graves’s Erickson Alumni Center Elizabeth Stoloff Vehse Thesis submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Kristina Olson, M.A., Chair Janet Snyder, Ph.D. -

BIOGRAPHY LUDWIG MIES VAN DER ROHE 1886 Born in Aachen

BIOGRAPHY LUDWIG MIES VAN DER ROHE 1886 Born in Aachen on March 27 1899–1902 Training in various fields associated with construction (Gewerbeschule Aachen, masonry apprenticeship, work in his father’s masonry business, designer of stucco ornaments) 1905 Move to Berlin, where he worked with Bruno Paul 1908–1911 Position at Peter Behrens’ Berlin architectural firm 1912 Founds his own architectural firm in Berlin 1914 Drafted into the army, worked in various building companies 1921 Participation in a competition for an office building on Berlin’s Friedrichstraße (“Glashochhaus” [Glass Skyscraper], so-called “skin and bones architecture”) 1923 Membership, BDA (Bund Deutscher Architekten, German Association of Architects) 1924 Co-founder, “Der Ring” (The Ring), a group of avant-garde architects 1924 Membership, DWB (Deutscher Werkbund) 1927 Artistic director, model residential development Am Weißenhof in Stuttgart, as part of the Stuttgart Werkbundausstellung “Die Wohnung” 1926 Leaves the BDA (conflict between traditionalists and modernists) 1928/29 German Pavilion, World Exposition, Barcelona 1929/30 Construction of Villa Tugendhat, Brünn (Brno) 1930–1933 Director of the Bauhaus in Dessau and Berlin (1932–33) 1938 Emigration to Chicago, director, Department of Architecture, Armour Institute of Technology (later Illinois Institute of Technology) 1938–1969 Architecture office, Chicago, key works in the International Style As of 1950 Development of interiors free of supports with hall structures involving broad roofs (e.g., Farnsworth House, near Plano in Illinois, 1950/51) 1954–1958 Construction of the Seagram Building, New York 1965–1968 Construction of the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin 1969 Died in Chicago on August 17 Page 1 of 2 CONSTRUCTION HISTORY OF THE NEUE NATIONALGALERIE „The building itself is the first artwork to greet the visitor“ Werner Haftmann, director of the Nationalgalerie, 1968–1974 1961 For political reasons, West Berlin seeks to gain Mies van der Rohe for a Berlin building project of cultural and educational relevance. -

Social Housing in Mies Van Der Rohe9s Lafayette Towers

1999 ACSA INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCEmROME 161 Luxury and Fate: Social Housing in Mies Van Der Rohe9sLafayette Towers JANINE DEBANNE iversity of Detroit Mercy INTRODUCTION Lafayette Park sits immediately to the east of Detroit's Central Business District, severed from it by an expressway that runs northward toward the distant suburbs. Icon of the urban renewal movement, it is the fruit of a collaboration between urban planner Ludwig Hilberseimer and architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Mies' largest realized residential project. The reasons that motivated its inception were not unusual. Like many American cities, Detroit faced the problem of exodus to the suburbs and the deterioration of inner city residential neighborhoods. Because of its origins in urban renewal, it has perennially echoed the economic and social transfor- mations taking placein thecity at large.' Specifically,LafayettePark has been involved in a complex relationship with the city's poor, both causing them to lose their homes in the 1950's and beckoning them back in the early nineteen nineties after the worst years of Detroit's urban crisis.' In sharp contrast to his residential towers for Chicago, Mies can der Rohe's architecture was confronted in Detroit Fig. I. Lafayette Park viewed from downtown Detroit, figuring the now with a set ofcircurnstances under which it \vould be forced todisplay demolished Hudson Building in foreground. its own contradictions. DESCRIPTION AND HISTORY The twenty-one low-rise townhouse buildings designed by Mies vander Rohestill shimmeragainstthe backdropofAlfredCaldwell's flowing landscapes of footpaths. His three high-rise towers, with their precise clear aluminum curtain walled faAades, stand in sharp contrast to the ruination of the surrounding areas.' If from adistance this place appears to be unmarked by time, it is nonetheless woven into the very coniplex social and human fabric of Detroit's post- industrial history. -

Detroit Modern Lafayette/Elmwood Park Tour

Detroit Modern Lafayette/Elmwood Park Tour DETROIT MODERN Lafayette Park/Elmwood Park Biking Tour Tour begins at the Gratiot Avenue entrance to the Dequindre Cut and ends with a ride heading north on the Dequindre Cut from East Lafayette Street. Conceived in 1946 as the Gratiot Redevelopment Project, Lafayette Park was Detroit’s first residential urban renewal project. The nation’s pioneering effort under the Housing Act of 1949; it was the first phase of a larger housing redevelopment plan for Detroit. Construction began at the 129-acre site in 1956. The site plan for Lafayette Park was developed through a collabora- tive effort among Herbert Greenwald, developer; Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, architect; Ludwig Hilberseimer, city planner; and Alfred Caldwell, landscape architect. Greenwald had a vision of creating a modern urban neighborhood with the amenities of a suburb. Bounded by East Lafayette, Rivard, Antietam and Orleans Streets, Lafayette Park is based on the ‘super- block’ plan that Mies van der Rohe and Hilberseimer devised in the mid-1950s. The 13-acre, city-owned park is surrounded by eight separate housing components, a school and a shopping center. Mies van de Rohe designed the high-rise Pavilion Apartment buildings, the twin Lafayette Towers, and the low-rise townhouses and court houses in the International style for which he is famous. They are his only works in Michigan and the largest collection of Mies van de Rohe-designed residential buildings in the world. Caldwell’s Prairie style landscape uses native trees, curving pathways, and spacious meadows to create natural looking landscapes that contrast with the simplicity of the buildings and the density of the city. -

Mies Van Der Rohe's Compromise with the Nazis

WORKSHOP3 Mies van der Rohe's Compromise with the Nazis Celina R. Welch I gratefuffy acknowledge the help of Charles Jencks, without who's guidance and support this paper would never have happened. Leaders of the Modem Movement in architecture typically have been portrayed as standing above politics and in opposition to reactionary social movements such as Fascism . But over the last thirty years it has become apparent that this picture of moral probity is far from clear. The Modemists, perhaps because of a pragmatic outlook, and a philosophical view that stresses success, functionalism and power, have more often than is thought, collaborated with repressive regimes. Their record is not as pure as their defenders would like. As the complicated case of the Quantum physicist Werner Heisenberg has recently revealed, collaboration of a top professional with the Nazi hierarchy has many benign motives as weil as negative consequences. This paper will explore the moral ambiguities of one Modemist leader, Mies van der Rohe, to become a, perhaps the , architect of Germany (Fig. 1). My intention is not to censure, but to elucidate the moral ambiguities of his position; it is more typical of architects' relations to the power structure than most apologists of the Modern Movement would like to admit. Mies van der Rohe was one ot the most central figures of the Modem Movement. In 1924, he became chairman and director of the architectural exhibitions for the Novembergruppe, the main outlet of the avant-garde in Berlin. This was in addition to being one of the founding members of the Ring, the elite cell of Berlin architects that helped to establish the postwar Modem Movement.