Interview with Kirk Brown # ISG-A-L-2009-044 Interview # 1: December 22, 2009 Interviewer: Mike Czaplicki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tunnelvision a Publication for Alumni of Student Media at Vanderbilt University ALUMNI UPDATES GALORE! H Student Media Alumni Updates Begin on Page 3…

Issue 10 H Fall 2008 HAVE A BLOG? We would like to include your blog in the BLOG ROLL of future issues. Learn more at the end of the Alumni Updates … page 8. tunnelvision A publication for alumni of student media at Vanderbilt University ALUMNI UPDATES GALORE! H Student Media Alumni updates begin on page 3… TUNNEL NEWS INTRODUCING… The Vanderbilt Political Review Nonpartisan political discus- sion is the focus of The Vanderbilt Political Review, a new VSC publi- cation that launched in the fall. Jadzia Butler, a junior in Arts and Science, started the politi- cal journal to feature academic Butler during an appearance on MSNBC. essays written by students, fac- ulty and alumni. Alumni con- tributors have included Sen. Lamar Alexander (B.A., 1962) and Willie Geist (B.A., 1997), co-host of “Morning Joe” on MSNBC. Butler invites alumni to send questions, comments and submissions to vanderbiltpoliti- [email protected]. Olney speaks with a few members of The Vanderbilt Hustler sports staff in the Student Media Newsroom during a recent visit to campus. Vanderbilt Fashion Quarterly Students with a passion for fashion have a new outlet for expressing their interest in style Olney visits different campus and design. Vanderbilt Fashion Quarterly is a new publication by Tim Ghianni, Journalist-in-Residence for Vanderbilt Student Communications started by Lauren Elizabeth Junge, a sophomore in Arts and Vanderbilt’s increasing student diversity, “I knew when I was 15 that I wanted to ham sandwiches in the basement of Sarratt. Science who plans to create a its tolerance and outreach have made Buster be a sportswriter,” says Olney. -

Interview with Gene Reineke # ISG-A-L-2009-038 Interview # 1: December 7, 2009 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with Gene Reineke # ISG-A-L-2009-038 Interview # 1: December 7, 2009 Interviewer: Mark DePue COPYRIGHT The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 DePue: Today is Monday, December 7, 2009. My name is Mark DePue; I’m the director of oral history at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. I’m here this afternoon with Eugene Reineke, but you mentioned usually you’re known as Gene. Reineke: That’s correct, Mark. DePue: Why don’t you tell us where we are. Reineke: We’re here at my current employer, which is Hill & Knowlton, Inc. It’s a public relations firm, and we’re located at the Merchandise Mart in downtown Chicago. DePue: Which has a fascinating history itself. Someday I’ll have to delve into that one. We’re obviously here to talk about your experiences in the Edgar administration, but you had a lot of years working with Jim Thompson as well, so we’re going to take quite a bit of time. In today’s session, I don’t know that we’ll get to much of the Edgar experience because you’ve got enough information to talk about before that time, which is valuable history for us. -

Interview with Jim Edgar # ISG-A-L-2009-019.26 Interview # 26: December 14, 2010 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with Jim Edgar # ISG-A-L-2009-019.26 Interview # 26: December 14, 2010 Interviewer: Mark DePue DePue: The next person I wanted to ask you about is President Barack Obama. We had talked about him before, but it was always in the context of these other decisions that you were making or with the Blagojevich situation. What do you think about his emergence as a politician? Edgar: Oh, it’s phenomenal. I mean, here’s a guy that’s a state senator, and all of a sudden he’s president (laughs) of the United States within a matter of, what, a little more than two years. That’s a phenomenal accomplishment. DePue: Did he have a prominent role, as you recall, in the Illinois Senate? Edgar: No, no. When I was there, he was a freshman member, and he was in the minority party, so that’s about as insignificant as you could be. I think he was elected in ’96, so the last two years I was governor, he was in the state Senate. But I remember early in that session after the election, my staff person who was working the Senate came to me and said, “Boy, there’s really a bright new African American in the Senate. He is really impressive.” I was rather dubious. I had heard that before. As I often said, when I was a young person, we thought Jesse Jackson was really special; then I think most of us decided that wasn’t true. So I was a little… They make good speeches; sometimes they don’t follow up. -

The 2014 Illinois Governor Race: Quinn Vs Rauner John S

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC The imonS Review (Occasional Papers of the Paul Paul Simon Public Policy Institute Simon Public Policy Institute) 1-2015 The 2014 Illinois Governor Race: Quinn vs Rauner John S. Jackson Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/ppi_papers Paper #40 of the Simon Review Recommended Citation Jackson, John S., "The 2014 Illinois Governor Race: Quinn vs Rauner" (2015). The Simon Review (Occasional Papers of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute). Paper 40. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/ppi_papers/40 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Simon Review (Occasional Papers of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute) by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Simon Review The 2014 Illinois Governor Race: Quinn vs. Rauner By: John S. Jackson Paper #40 January 2015 A Publication of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute Southern Illinois University Carbondale Author’s Note: I want to thank Cary Day, Jacob Trammel and Roy E. Miller for their valuable assistance on this project. THE SIMON REVIEW The Simon Review papers are occasional nonacademic papers of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at Southern Illinois University Carbondale that examine and explore public policy issues within the scope of the Institute’s mission and in the tradition of the University. The Paul Simon Public Policy Institute acts on significant and controversial issues impacting the region, the state, the nation, and the world. -

How and Why Illinois Abolished the Death Penalty

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 30 Issue 2 Article 2 December 2012 How and Why Illinois Abolished the Death Penalty Rob Warden Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Rob Warden, How and Why Illinois Abolished the Death Penalty, 30(2) LAW & INEQ. 245 (2012). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol30/iss2/2 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. 245 How and Why Illinois Abolished the Death Penalty Rob Wardent Introduction The late J. Paul Getty had a formula for becoming wealthy: rise early, work late-and strike oil.' That is also the formula for abolishing the death penalty, or at least it is a formula-the one that worked in Illinois. When Governor Pat Quinn signed legislation ending capital punishment in Illinois on March 9, 2011, he tacitly acknowledged the early rising and late working that preceded the occasion. "Since our experience has shown that there is no way to design a perfect death penalty system, free from the numerous flaws that can lead to wrongful convictions or discriminatory treatment, I have concluded that the proper course of action is to abolish it." 2 The experience to which the governor referred was not something that dropped like a gentle rain from heaven upon the place beneath and seeped into his consciousness by osmosis. Rather, a cadre of public defenders, pro bono lawyers, journalists, academics, and assorted activists, devoted tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of hours, over more than three decades, to the abolition movement. -

Sex Is Not Without Its Advantages

Sex is not without its advantages Now that the baseball season in town is effectively over, cook up a good local sex scandal or two to divert attention away from these far more serious issues. July 25, 2013 By Allen R. Sanderson As Chicago's homicide rate and Illinois' pension crisis continue to garner national media attention and spiral out of control, our city and state politicians are Nero-like in their responses. We need some bold action, or at least diversion, and soon, or we risk sinking even lower on the political radar screen — we are only fifth in state population and thanks to Toronto, we are now the fifth-largest city in North America. The "flyover" section of our country has a lot to learn from the coasts — and even abroad. Thus I offer this humble suggestion: Now that the baseball season in town is effectively over, cook up a good local sex scandal or two to divert attention away from these far more serious issues. I'm not asking for an Anthony Weiner on any given day. And not even a John Edwards. But can't we at least produce in this city and state someone on the order of Eliot Spitzer or Silvio Berlusconi? I'd even settle for Mark Sanford or David Vitter. Sure, we have had more than our fair share of high-profile felons — former Govs. Rod Blagojevich, George Ryan, Dan Walker, Otto Kerner. But for what? Corruption, racketeering, bribery, fraud. Boring stuff. Where were the sexting emails, prostitutes, strippers, mistresses, photos of a blue dress or the Appalachian Trail? Our about-one-scandal-per-year Chicago aldermen have gotten their three squares a day at the public trough for the mundane: corruption, bribery, tax evasion. -

Radio Stations

Date Contacted Comments RA_Call EMail FirstName Bluegrass(from Missy) James H. Bluegrass(from Missy) Joe Bluegrass(from Missy) James H. Sent dpk thru Airplay Direct [email protected] 2/9/2014 Bluegrass(from Missy) m Tom Sent dpk thru Airplay Direct cindy@kneedeepi 2/9/2014 Bluegrass(from Missy) nbluegrass.com Cindy Sent dpk thru Airplay Direct drdobro@mindspri 2/9/2014 Bluegrass(from Missy) ng.com Lawrence E. Sent dpk thru Airplay Direct georgemcknight@ 2/9/2014 Bluegrass(from Missy) telus.net George Sent dpk thru Airplay Direct greatstuffradio@y 2/9/2014 Bluegrass(from Missy) ahoo.com Gene Sent dpk thru Airplay Direct jadonchris@netco 2/9/2014 Bluegrass(from Missy) mmander.com Jadon Sent dpk thru Airplay Direct roy@mainstreetbl 2/9/2014 Bluegrass(from Missy) uegrass.com Roy From Americana Music Association reporting stations list ACOUSTIC CAFE Rob From Americana Music Association reporting stations list ALTVILLE Vicki From Americana Music Association reporting stations list Country Bear Stan From Americana Music Association reporting stations list Current 89.3 David From Americana Music Association reporting stations list Farm Fresh Radio Chip From Americana Music Association reporting stations list Folk Alley - WKSU Linda From Americana Music Association reporting stations list FolkScene Roz Sending physical copy 2/2014 per his arthu2go@yahoo. facebook request. Bluegrass(from Missy) 105.9 Bishop FM co.uk Terry Sent dpk thru Airplay Direct lindsay@ozemail. 2/9/2014 Bluegrass(from Missy) 2RRR com.au Lindsay Sent dpk thru Airplay Direct tony.lake@amtac. 2/9/2014 Bluegrass(from Missy) 400R net Tony Sent dpk thru Airplay Direct bluemoon@bluegr 2/9/2014 Bluegrass(from Missy) ACTV-4 asstracks.net Jon C. -

2009 Annual Report-2.Pdf

Contents Page Letter from Co-Chairs .................................................. 1 2009 Federal Legislative Goals ...................................... 2 2009 State Legislative Goals ......................................... 2 2009 Accomplishments ................................................ 3 2009 Highlights ............................................................ 8 TFIC Officers & Committee Chairs .......................... 14 IDOT Districts and Regional Offices ......................... 15 IDOT Map of Districts and Regional Offices ............. 15 Illinois Congressional District Maps ........................... 16 Illinois Congressional Directory ................................. 18 Illinois General Assembly Directory ........................... 21 2009 TFIC Member Organizations ...... inside back cover Mission Statement .......................................... back cover How to Become a Member Membership in TFIC is open to organizations, associations, unions, local governments, regional groups and chambers of commerce from throughout Illinois. Any organization with members who realize the importance of transportation to Illi- nois jobs and the economy is encouraged to join. Contact Eric Fields, TFIC Membership Chair, at the Associ- ated General Contractors of Illinois, 217/789-2650; [email protected] or any member of the TFIC steering com- mittee. 312 S. Fourth Street, Suite 200 Springfield, Illinois 62701 217/572-1270 www.tficillinois.org For the past several years, TFIC has been working to support passage of a comprehensive -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 150 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 18, 2004 No. 133 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was PRAYER THE JOURNAL called to order by the Speaker pro tem- The Chaplain, the Reverend Daniel P. The SPEAKER pro tempore. The pore (Mr. SIMPSON). Coughlin, offered the following prayer: Chair has examined the Journal of the Blessed be the God and Father of us f all, for he has chosen you to be rep- last day’s proceedings and announces resentatives of his people. to the House his approval thereof. Lord God, what a blessing it is to re- DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- alize one has a calling at a particular PRO TEMPORE nal stands approved. time for a specific service to accom- plish Your holy will. It is then we truly The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- f fore the House the following commu- have purpose. nication from the Speaker: Both in great and small things, we WASHINGTON, DC, become neither overwhelmed nor dis- PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE November 18, 2004. dainful. Every task can be embraced. Every duty fulfilled. Every burden can The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the I hereby appoint the Honorable MICHAEL K. be lightened by the knowledge that gentleman from Wisconsin (Mr. GREEN) SIMPSON to act as Speaker pro tempore on come forward and lead the House in the this day. -

Bloch Rubin ! ! a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of The

! ! ! ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! by! Ruth Frances !Bloch Rubin ! ! A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley ! Committee in charge: Professor Eric Schickler, Chair Professor Paul Pierson Professor Robert Van Houweling Professor Sean Farhang ! ! Fall 2014 ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! Copyright 2014 by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abstract ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Eric Schickler, Chair The purpose of this dissertation is to supply a simple and synthetic theory to help us to understand the development and value of organized intraparty blocs. I will argue that lawmakers rely on these intraparty organizations to resolve several serious collective action and coordination problems that otherwise make it difficult for rank-and-file party members to successfully challenge their congressional leaders for control of policy outcomes. In the empirical chapters of this dissertation, I will show that intraparty organizations empower dissident lawmakers to resolve their collective action and coordination challenges by providing selective incentives to cooperative members, transforming public good policies into excludable accomplishments, and instituting rules and procedures to promote group decision-making. And, in tracing the development of intraparty organization through several well-known examples of party infighting, I will demonstrate that intraparty organizations have played pivotal — yet largely unrecognized — roles in critical legislative battles, including turn-of-the-century economic struggles, midcentury battles over civil rights legislation, and contemporary debates over national health care policy. -

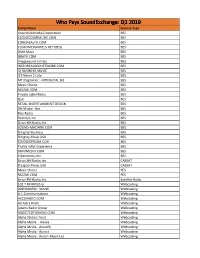

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media -

Tunnelvision Their Lives … a Publication for Alumni of Student Media at Vanderbilt University Page 3 Lillian Gu and Jerry Yen (Page 6)

Issue 12 H Fall 2009 DIRECTOR HONOR…Director of Student Media, Chris Carroll, named to College Media Advisers' national adviser Hall of Fame…see page 7 ALUMNI ALUMNI UPDATES GALORE! Several of your former staff members and classmates give a glimpse into tunnelvision their lives … A publication for alumni of student media at Vanderbilt University page 3 Lillian Gu and Jerry Yen (page 6) TUNNEL NEWS TORCH WINS NATIONAL AWARD The Vanderbilt Torch, Vanderbilt Student Communications' con- servative and libertarian publica- tion, won the award for best new media at the Collegiate Network’s annual Editors Conference this November. This year’s conference was held in San Antonio, Texas, and Torch contributors Katherine Miller and Patrick McBride attended on behalf of the publication. The Torch’s current editor-in-chief is senior Frannie Boyle. To see the Torch online, visit www.vutorch. com, or www.vandyright.com for its corresponding blog. HUSTLER NAMED PACEMAKER FINALIST The Vanderbilt Hustler was named a finalist for the Associated Collegiate Press Pacemaker award for the 2008-09 academic year. This award is considered to be the highest honor for collegiate The inaugural class of the Vanderbilt Student Media Hall of Fame (l-r): Sen. Lamar Alexander (’62), Roy Blount Jr. (’63), Mary Elson (’74), Skip Bayless (’74) and Sam Feist (’91) after the induction ceremony held in Sarratt Cinema. newspapers. Michael Warren served as editor-in-chief in the fall of 2009, and Sydney Wilmer was editor-in-chief in the spring of 2009. VSC inducts inaugural class of the Vanderbilt Student Media H H H WHY HALLby Justin TardiffOF, Student Media NewsF EditorAME TUNNEL Vanderbilt Student Communications to The Hustler offices and launched her on a inducted the first five members into its career in journalism.