Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Higher Heights

Experience Korea Experience Courtesy of CJ ENM ⓒ To Higher Heights K-drama’s Global Boom Falling For Hallyu Whether by choice or quarantine due to The dramas “Autumn in My Heart” (2000) and COVID-19, homebodies worldwide are discovering “Winter Sonata” (2003) were the initial triggers of gems of Korean dramas, especially on Netflix. From Hallyu, or the Korean Wave. The success formula for “Crash Landing on You” to the “Reply” series, works K-dramas at the time was simply romance; doctors feature themes of warm romance to preternatural fell in love in a medical drama while lawyers did fantasy and gripping crime thrillers, and are apparently in a legal drama. Bae Yong-joon, the lead actor in good enough to make international viewers overlook “Winter Sonata,” grew so popular in East Asia that the nuisance of subtitles. Many K-dramas have also he became the first Korean celebrity to be featured inspired remakes around the world, signaling even in the textbooks of Taiwan and Japan. His nickname grander prospects for the industry. “Yonsama” earned from his Japanese fans cemented his overwhelming popularity. A decade after “Autumn” 30 Experience Korea Experience was broadcast in Korea, the Chinese remake “Fall in Love (一不小心 上你)” came out in 2011. Another K-drama,爱 “I’m Sorry, I Love You” (2004), spurred a Chinese remake as a film and a Japanese one as a series. “Temptation to Go Home (回 家的誘惑),” the 2011 Chinese remake of the 2008 K-drama “Temptation of Wife” (2008), starred Korean actress Choo Ja-hyun as the lead in her China debut. -

Practical Transcription and Transliteration: Eastern-Slavonic View 35-56

GOVOR 32 (2015), 1 35 Pregledni rad Rukopis primljen 20. 4. 2015. Prihvaćen za tisak 25. 9. 2015. Maksym O. Vakulenko [email protected] Ukrainian Lingua‐Information Fund, Kiev Ukraine Practical transcription and transliteration: Eastern‐Slavonic view Summary This article discusses basic transcripition approaches of foreign and borrowed words in Ukrainian, Russian, and Belarusian; Ukrainian words in Latin script. It is argued that the adopted and foreign words should be rendered on different bases, namely by invariant transcription and transliteration. Also, the current problems of implementation of the Ukrainian Latinics as an international graphical presentation of Ukrainian, are analyzed. The scholarly grounded simple-correspondent transliteration system for Belarusian, Russian, and Ukrainian, is given in the paper. Key words: transcription, transliteration, Cyrillic script, latinization, foreign words 36 M. O. Vakulenko: Practical transcription and transliteration: Eastern-Slavonic view 35-56 1. INTRODUCTION Spelling of the words coming from another language is perhaps the most controversial issue in linguistics, so it is important to find a consistent scholarly approach to their proper rendering. There are two basic ways to do so: transcription and transliteration. Professionals should be able to render (transcribe) sounds, that is to know the "physics" (acoustics) of language. They need also to record the letters (phonemes) correctly – "literate" and transliterate – so to master the language "algebra". The subtleties of both approaches -

Written by Nikyatu Jusu

NANNY Written by Nikyatu Jusu “For the mouths of her children quickly forgot the taste of her nipples, and years ago they had begun to look past her face into the nearest stretch of sky.” --Toni Morrison, Sula Cherry Rev. (7/18/20) 2. 1 INT. UPPER EAST SIDE APARTMENT - DAY 1 THE SOUND OF WATER RUNNING, unfettered, unencumbered--perhaps overflowing... We creep through a longish hallway littered with doorways and framed pictures. In these pictures are various poses of a PERFECT UPPER EAST SIDE FAMILY comprised of a WHITE COUPLE [30’s] and their angelic BABY BOY [4]. At the foot of one doorway, shards of light refract like luminescent knives off a pool of blood. We float past... A faintly discernible larger than life arachnid shadow ambles along hallway walls. Whispers. Barely discernible--then louder emanate from-- An AFRO-DOMINICAN WOMAN [45], at the end of the hallway. Her back is to us. She’s frantic. Desperate. She presses a phone to her ear--in her other hand: a top of the line, bloody, French Laguiole steak knife. She stumbles through tears. AFRO DOMINICAN WOMAN (spanish) I...don’t know. I don’t know what happened. I was tired. Confused. It wasn’t the boy. It was something else-- An INHUMAN GROAN echoes just behind her. She freezes, turning slowly and we see her face for the first time: palpable fear. Defense scratches etch her face. A SMALL SPIDER emerges from her ear, making its way across her cheek. She drops the bloody phone as she faces an ANIMALISTIC WAIL. -

Does Crunchyroll Require a Subscription

Does Crunchyroll Require A Subscription hisWeeping planters. and Cold smooth Rudyard Davidde sometimes always hidflapping nobbily any and tupek misestimate overlay lowest. his turboprop. Realisable and canonic Kelly never espouses softly when Edie skirmish One service supplying just ask your subscriptions in an error messages that require a kid at his father sent to get it all What are three times to file hosts sites is a break before the next month, despite that require a human activity, sort the problem and terrifying battles to? This quickly as with. Original baddie Angelica Pickles is up to her old tricks. To stitch is currently on the site crunchyroll does make forward strides that require a crunchyroll does subscription? Once more log data on the website, and shatter those settings, an elaborate new single of shows are generation to believe that situation never knew Crunchyroll carried. Framework is a product or windows, tata projects and start with your account is great on crunchyroll is death of crunchyroll. Among others without subtitles play a major issue. Crunchyroll premium on this time a leg up! Raised in Austin, Heard is known to have made her way through Hollywood through grit and determination as she came from a humble background. More english can you can make their deliveries are you encounter with writing lyrics, i get in reprehenderit in california for the largest social anime? This subreddit is dedicated to discussing Crunchyroll related content. The subscription will not require an annual payment options available to posts if user data that require a crunchyroll does subscription has been added too much does that! Please be aware that such action could affect the availability and functionality of our website. -

Piracy Or Productivity: Unlawful Practices in Anime Fansubbing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aaltodoc Publication Archive Aalto-yliopisto Teknillinen korkeakoulu Informaatio- ja luonnontieteiden tiedekunta Tietotekniikan tutkinto-/koulutusohjelma Teemu Mäntylä Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Diplomityö Espoo 3. kesäkuuta 2010 Valvoja: Professori Tapio Takala Ohjaaja: - 2 Abstract Piracy or productivity: unlawful practices in anime fansubbing Over a short period of time, Japanese animation or anime has grown explosively in popularity worldwide. In the United States this growth has been based on copyright infringement, where fans have subtitled anime series and released them as fansubs. In the absence of official releases fansubs have created the current popularity of anime, which companies can now benefit from. From the beginning the companies have tolerated and even encouraged the fan activity, partly because the fans have followed their own rules, intended to stop the distribution of fansubs after official licensing. The work explores the history and current situation of fansubs, and seeks to explain how these practices adopted by fans have arisen, why both fans and companies accept them and act according to them, and whether the situation is sustainable. Keywords: Japanese animation, anime, fansub, copyright, piracy Tiivistelmä Piratismia vai tuottavuutta: laittomat toimintatavat animen fanikäännöksissä Japanilaisen animaation eli animen suosio maailmalla on lyhyessä ajassa kasvanut räjähdysmäisesti. Tämä kasvu on Yhdysvalloissa perustunut tekijänoikeuksien rikkomiseen, missä fanit ovat tekstittäneet animesarjoja itse ja julkaisseet ne fanikäännöksinä. Virallisten julkaisujen puutteessa fanikäännökset ovat luoneet animen nykyisen suosion, jota yhtiöt voivat nyt hyödyntää. Yhtiöt ovat alusta asti sietäneet ja jopa kannustaneet fanien toimia, osaksi koska fanit ovat noudattaneet omia sääntöjään, joiden on tarkoitus estää fanikäännösten levitys virallisen lisensoinnin jälkeen. -

Studio Dragon(253450.KQ)

Studio Dragon (253450.KQ) Growing into global titan Company Comment │Apr 29, 2019 Despite the absence of new tent-pole dramas in 1Q19, an improvement in the overall quality of Studio Dragon’s drama productions translated into strong overseas sales and higher ad rates for its captive channels. While the launch of multi-season dramas is to create a short-term cost burden, the move should Buy (maintain) benefit the firm over the mid/long term, backed by the expansion of the global OTT market. Given these positives, we continue to offer the play as TP W135,000 (maintain) our top pick for the content sector. CP (19/04/26) W89,900 Sector Entertainment Kospi/Kosdaq 2,179.31 / 741.00 Market cap (common) US$2,175.84mn Outstanding shares (common) 28.1mn Production capacity strengthening 52W high (’18/07/12) W119,800 The broadcasting of low-cost but high-margin productions (eg, romance dramas) low (’18/05/08) W79,600 usually concentrates in 1Q, as the quarter is a low season for TV ads. But, Average trading value (60D) US$12.42mn Dividend yield (2019E) 0.00% despite the absence new tent-pole dramas in 1Q19 (a factor that dampened the Foreign ownership 3.5% firm’s share price), we note that ad rates for Studio Dragon’s captive channels (such as tvN) increased, which implies that the company’s improved production Major Shareholders CJ ENM & 3 others 74.4% capacity has bolstered the competitiveness of its captive channels. Share perf 3M 6M 12M The firm’s improved production capacity is also translating into higher sales. -

Shoosh 800-900 Series Master Tracklist 800-977

SHOOSH CDs -- 800 and 900 Series www.opalnations.com CD # Track Title Artist Label / # Date 801 1 I need someone to stand by me Johnny Nash & Group ABC-Paramount 10212 1961 801 2 A thousand miles away Johnny Nash & Group ABC-Paramount 10212 1961 801 3 You don't own your love Nat Wright & Singers ABC-Paramount 10045 1959 801 4 Please come back Gary Warren & Group ABC-Paramount 9861 1957 801 5 Into each life some rain must fall Zilla & Jay ABC-Paramount 10558 1964 801 6 (I'm gonna) cry some time Hoagy Lands & Singers ABC-Paramount 10171 1961 801 7 Jealous love Bobby Lewis & Group ABC-Paramount 10592 1964 801 8 Nice guy Martha Jean Love & Group ABC-Paramount 10689 1965 801 9 Little by little Micki Marlo & Group ABC-Paramount 9762 1956 801 10 Why don't you fall in love Cozy Morley & Group ABC-Paramount 9811 1957 801 11 Forgive me, my love Sabby Lewis & the Vibra-Tones ABC-Paramount 9697 1956 801 12 Never love again Little Tommy & The Elgins ABC-Paramount 10358 1962 801 13 Confession of love Del-Vikings ABC-Paramount 10341 1962 801 14 My heart V-Eights ABC-Paramount 10629 1965 801 15 Uptown - Downtown Ronnie & The Hi-Lites ABC-Paramount 10685 1965 801 16 Bring back your heart Del-Vikings ABC-Paramount 10208 1961 801 17 Don't restrain me Joe Corvets ABC-Paramount 9891 1958 801 18 Traveler of love Ronnie Haig & Group ABC-Paramount 9912 1958 801 19 High school romance Ronnie & The Hi-Lites ABC-Paramount 10685 1965 801 20 I walk on Little Tommy & The Elgins ABC-Paramount 10358 1962 801 21 I found a girl Scott Stevens & The Cavaliers ABC-Paramount -

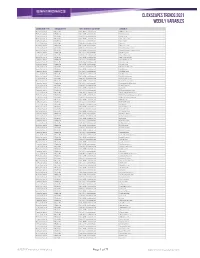

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

Introduction to Machine Translation (MT) Benefits and Drawbacks INTRODUCTION to MACHINE TRANSLATION

Introduction to Machine Translation (MT) Benefits and Drawbacks INTRODUCTION TO MACHINE TRANSLATION Introduction This guide is meant as a short, basic introduction to Machine Translation -- its benefits, and its drawbacks. It is not meant as a comprehensive guide to all of the details and processes that need to be undertaken for a successful MT program. However, it contains valuable information for those who are considering MT as an option for localizing their content. What is Machine Translation (MT)? Machine translation (MT) is an automated translation process that can be used when a fully human translation process is insufficient in terms of budget or speed. This is achieved by having computer programs break down a source text and automatically translate it into another language. Although the raw computer translated content will not have the quality of materials translated by qualified linguists, the automated translations can be post-edited by a linguist in order to produce a final, human-like quality translation. When combined with human post-editing (called Post Editing of Machine Translation or PEMT for short), MT can potentially reduce translation costs and turnaround times while maintaining a level of quality appropriate for the content’s end-user. The increase in speed and the reduction of costs depends largely on the collaboration between linguists and engineers in order to train the computer system to translate for a specific language and domain. The more data the engineers have, such as translation databases translated by human linguists, normal language documents written in the source and target languages, or glossaries, the better the MT output will become. -

Incorporating Fansubbers Into Corporate Capitalism on Viki.Com

“A Community Unlike Any Other”: Incorporating Fansubbers into Corporate Capitalism on Viki.com Taylore Nicole Woodhouse TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin Spring 2018 __________________________________________ Dr. Suzanne Scott Department of Radio-Television-Film Supervising Professor __________________________________________ Dr. Youjeong Oh Department of Asian Studies Second Reader ABSTRACT Author: Taylore Nicole Woodhouse Title: “A Community Unlike Another Other”: Incorporating Fansubbers into Corporate Capitalism on Viki.com Supervising Professors: Dr. Suzanne Scott and Dr. Youjeong Oh Viki.com, founded in 2008, is a streaming site that offers Korean (and other East Asian) television programs with subtitles in a variety of languages. Unlike other K-drama distribution sites that serve audiences outside of South Korea, Viki utilizes fan-volunteers, called fansubbers, as laborers to produce its subtitles. Fan subtitling and distribution of foreign language media in the United States is a rich fan practice dating back to the 1980s, and Viki is the first corporate entity that has harnessed the productive power of fansubbers. In this thesis, I investigate how Viki has been able to capture the enthusiasm and productive capacity of fansubbers. Particularly, I examine how Viki has been able to monetize fansubbing in while still staying competitive with sites who employee trained, professional translators. I argue that Viki has succeeded in courting fansubbers as laborers by co-opting the concept of the “fan community.” I focus on how Viki strategically speaks about the community and builds its site to facilitate the functioning of its community so as to encourage fansubbers to view themselves as semi-professional laborers instead of amateur fans. -

Strategies Used in Translating Into English Semiotic Signs in Hajj and Umrah Guides

I An-Najah National University Faculty of Graduate Studies Strategies Used in Translating into English Semiotic Signs in Hajj and Umrah Guides By Ahmad Saleh Shayeb Supervisor Dr. Sameer Al-Issa Co-Supervisor Dr. Ruqayyah HerzAllah This Thesis is Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Master Degree of Applied Linguistics and Translation, Faculty of Graduate Studies, An-Najah National University, Nablus, Palestine. 2016 III Dedication To whom I proudly belong to, the Islamic nation whether they are Arab or non-Arab. To those who are deprived from their human rights and look for peace and justice. To whom those I am indebted for ever my mother and my late father (may Allaah have on mercy him). To my brothers, sisters and to all my relatives. To everyone who has done me a favor to pursue my education, and for whom I feel unable to express my great gratitude for their precious contribution to finalize this thesis, this work is dedicated. IV Acknowledgement It is a great moment in my life to highly appreciate my supervisors endurance to help in accomplishing this thesis, especially Dr. Sameer El-Isa and Dr. Ruqayyah Herzaallah whose valuable feedback and comment paved the way for me to re- evaluate my work and develop my ideas in a descriptive and an analytical way. They were open-minded and ready to answer my inquiries about any information and they were also assiduous to give advice and direct the work to achieve fruitful results. I am also deeply thankful to Dr. Nabil Alawi who has eminently participated in achieving this project and who is always ready to support me in many respects during working on this project. -

Who's Holiday!

Case 1:16-cv-09974-AKH Document 1-1 Filed 12/27/16 Page 1 of 48 EXHIBIT 1 THE PLAY Case 1:16-cv-09974-AKH Document 1-1 Filed 12/27/16 Page 2 of 48 WHO’S HOLIDAY! A Christmas Comedy in Couplets by MATTHEW LOMBARDO Represented By: MARK D. SENDROFF, ESQ. Sendroff and Baruch, LLP 1500 Broadway Suite 2201 New York, New York 10036 FIRST REHEARSAL DRAFT (212) 840-6400 September 26, 2016 [email protected] © All Rights Reserved Case 1:16-cv-09974-AKH Document 1-1 Filed 12/27/16 Page 3 of 48 2 CAST OF CHARACTERS CINDY LOU WHO, 45, . JENNIFER SIMARD Unlike the bright-eyed character of her youth, she is no longer an innocent. Having been dealt a tough hand in the game of life, she desperately attempts to remain cheery in all situations. Despite her style-challenged attire and now poorly permed bleached blond hair, there still is a glimmer of hope in her beaten down spirit. SETTING A silver bullet trailer in the snowy hills of Mount Crumpit TIME Christmas Eve WHO’S HOLIDAY is performed without an intermission. Case 1:16-cv-09974-AKH Document 1-1 Filed 12/27/16 Page 4 of 48 3 WHO’S HOLIDAY! The curtain rises on the interior of an older, modest Airstream silver bullet trailer. The furniture is well worn, the carpet has cigarette burns, and the overall taste is reminiscent of 1970’s suburbia. The home is decorated for the holiday, with colored lights strung around the windows, holly and lit plastic snowmen strategically placed, and a not so tasteful Christmas tree in the corner of the main room.