(In Some Fictions) Everything Is True

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classifying Material Implications Over Minimal Logic

Classifying Material Implications over Minimal Logic Hannes Diener and Maarten McKubre-Jordens March 28, 2018 Abstract The so-called paradoxes of material implication have motivated the development of many non- classical logics over the years [2–5, 11]. In this note, we investigate some of these paradoxes and classify them, over minimal logic. We provide proofs of equivalence and semantic models separating the paradoxes where appropriate. A number of equivalent groups arise, all of which collapse with unrestricted use of double negation elimination. Interestingly, the principle ex falso quodlibet, and several weaker principles, turn out to be distinguishable, giving perhaps supporting motivation for adopting minimal logic as the ambient logic for reasoning in the possible presence of inconsistency. Keywords: reverse mathematics; minimal logic; ex falso quodlibet; implication; paraconsistent logic; Peirce’s principle. 1 Introduction The project of constructive reverse mathematics [6] has given rise to a wide literature where various the- orems of mathematics and principles of logic have been classified over intuitionistic logic. What is less well-known is that the subtle difference that arises when the principle of explosion, ex falso quodlibet, is dropped from intuitionistic logic (thus giving (Johansson’s) minimal logic) enables the distinction of many more principles. The focus of the present paper are a range of principles known collectively (but not exhaustively) as the paradoxes of material implication; paradoxes because they illustrate that the usual interpretation of formal statements of the form “. → . .” as informal statements of the form “if. then. ” produces counter-intuitive results. Some of these principles were hinted at in [9]. Here we present a carefully worked-out chart, classifying a number of such principles over minimal logic. -

Demystifying the Saint

DEMYSTIFYING THE SAINT: JAY L. GARFIELDʼS RATIONAL RECONSTRUCTION OF NĀGĀRJUNAʼS MĀDHYAMAKA AS THE EPITOME OF CONTEMPORARY CROSS-CULTURAL PHILOSOPHY TIINA ROSENQVIST Tampereen yliopisto Yhteiskunta- ja kulttuuritieteiden yksikkö Filosofian pro gradu -tutkielma Tammikuu 2011 ABSTRACT Cross-cultural philosophy approaches philosophical problems by setting into dialogue systems and perspectives from across cultures. I use the term more specifically to refer to the current stage in the history of comparative philosophy marked by the ethos of scholarly self-reflection and the production of rational reconstructions of foreign philosophies. These reconstructions lend a new kind of relevance to cross-cultural perspectives in mainstream philosophical discourses. I view Jay L. Garfieldʼs work as an example of this. I examine Garfieldʼs approach in the context of Nāgārjuna scholarship and cross-cultural hermeneutics. By situating it historically and discussing its background and implications, I wish to highlight its distinctive features. Even though Garfield has worked with Buddhist philosophy, I believe he has a lot to offer to the meta-level discussion of cross-cultural philosophy in general. I argue that the clarity of Garfieldʼs vision of the nature and function of cross-cultural philosophy can help alleviate the identity crisis that has plagued the enterprise: Garfield brings it closer to (mainstream) philosophy and helps it stand apart from Indology, Buddhology, area studies philosophy (etc). I side with Garfield in arguing that cross- cultural philosophy not only brings us better understanding of other philosophical traditions, but may enhance our self-understanding as well. I furthermore hold that his employment of Western conceptual frameworks (post-Wittgensteinian language philosophy, skepticism) and theoretical tools (paraconsistent logic, Wittgensteinian epistemology) together with the influence of Buddhist interpretative lineages creates a coherent, cogent, holistic and analytically precise reading of Nāgārjunaʼs Mādhyamaka philosophy. -

On Basic Probability Logic Inequalities †

mathematics Article On Basic Probability Logic Inequalities † Marija Boriˇci´cJoksimovi´c Faculty of Organizational Sciences, University of Belgrade, Jove Ili´ca154, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] † The conclusions given in this paper were partially presented at the European Summer Meetings of the Association for Symbolic Logic, Logic Colloquium 2012, held in Manchester on 12–18 July 2012. Abstract: We give some simple examples of applying some of the well-known elementary probability theory inequalities and properties in the field of logical argumentation. A probabilistic version of the hypothetical syllogism inference rule is as follows: if propositions A, B, C, A ! B, and B ! C have probabilities a, b, c, r, and s, respectively, then for probability p of A ! C, we have f (a, b, c, r, s) ≤ p ≤ g(a, b, c, r, s), for some functions f and g of given parameters. In this paper, after a short overview of known rules related to conjunction and disjunction, we proposed some probabilized forms of the hypothetical syllogism inference rule, with the best possible bounds for the probability of conclusion, covering simultaneously the probabilistic versions of both modus ponens and modus tollens rules, as already considered by Suppes, Hailperin, and Wagner. Keywords: inequality; probability logic; inference rule MSC: 03B48; 03B05; 60E15; 26D20; 60A05 1. Introduction The main part of probabilization of logical inference rules is defining the correspond- Citation: Boriˇci´cJoksimovi´c,M. On ing best possible bounds for probabilities of propositions. Some of them, connected with Basic Probability Logic Inequalities. conjunction and disjunction, can be obtained immediately from the well-known Boole’s Mathematics 2021, 9, 1409. -

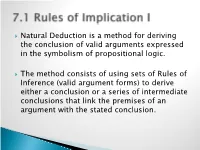

7.1 Rules of Implication I

Natural Deduction is a method for deriving the conclusion of valid arguments expressed in the symbolism of propositional logic. The method consists of using sets of Rules of Inference (valid argument forms) to derive either a conclusion or a series of intermediate conclusions that link the premises of an argument with the stated conclusion. The First Four Rules of Inference: ◦ Modus Ponens (MP): p q p q ◦ Modus Tollens (MT): p q ~q ~p ◦ Pure Hypothetical Syllogism (HS): p q q r p r ◦ Disjunctive Syllogism (DS): p v q ~p q Common strategies for constructing a proof involving the first four rules: ◦ Always begin by attempting to find the conclusion in the premises. If the conclusion is not present in its entirely in the premises, look at the main operator of the conclusion. This will provide a clue as to how the conclusion should be derived. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in the consequent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via modus ponens. ◦ If the conclusion contains a negated letter and that letter appears in the antecedent of a conditional statement in the premises, consider obtaining the negated letter via modus tollens. ◦ If the conclusion is a conditional statement, consider obtaining it via pure hypothetical syllogism. ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a disjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via disjunctive syllogism. Four Additional Rules of Inference: ◦ Constructive Dilemma (CD): (p q) • (r s) p v r q v s ◦ Simplification (Simp): p • q p ◦ Conjunction (Conj): p q p • q ◦ Addition (Add): p p v q Common Misapplications Common strategies involving the additional rules of inference: ◦ If the conclusion contains a letter that appears in a conjunctive statement in the premises, consider obtaining that letter via simplification. -

Dialectic, Rhetoric and Contrast the Infinite Middle of Meaning

Dialectic, Rhetoric and Contrast The Infinite Middle of Meaning Richard Boulton St George’s, University of London; Kingston University Series in Philosophy Copyright © 2021 Richard Boulton. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200 C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware, 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in Philosophy Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931318 ISBN: 978-1-64889-149-6 Cover designed by Aurelien Thomas. Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Table of contents Introduction v Chapter I Method 1 Dialectic and Rhetoric 1 Validating a Concept Spectrum 12 Chapter II Sense 17 Emotion 17 Rationality 23 The Absolute 29 Truth 34 Value 39 Chapter III Essence 47 Meaning 47 Narrative 51 Patterns and Problems 57 Existence 61 Contrast 66 Chapter IV Consequence 73 Life 73 Mind and Body 77 Human 84 The Individual 91 Rules and Exceptions 97 Conclusion 107 References 117 Index 129 Introduction This book is the result of a thought experiment inspired by the methods of dialectic and rhetoric. -

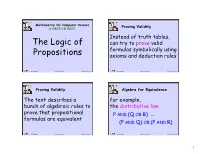

Propositional Logic (PDF)

Mathematics for Computer Science Proving Validity 6.042J/18.062J Instead of truth tables, The Logic of can try to prove valid formulas symbolically using Propositions axioms and deduction rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.1 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.2 Proving Validity Algebra for Equivalence The text describes a for example, bunch of algebraic rules to the distributive law prove that propositional P AND (Q OR R) ≡ formulas are equivalent (P AND Q) OR (P AND R) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.3 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.4 1 Algebra for Equivalence Algebra for Equivalence for example, The set of rules for ≡ in DeMorgan’s law the text are complete: ≡ NOT(P AND Q) ≡ if two formulas are , these rules can prove it. NOT(P) OR NOT(Q) Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.5 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.6 A Proof System A Proof System Another approach is to Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a start with some valid particularly elegant example of this idea. formulas (axioms) and deduce more valid formulas using proof rules Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.7 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.8 2 A Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ proof system is a Axioms: particularly elegant example of 1) (¬P → P) → P this idea. It covers formulas 2) P → (¬P → Q) whose only logical operators are 3) (P → Q) → ((Q → R) → (P → R)) IMPLIES (→) and NOT. The only rule: modus ponens Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.9 Albert R Meyer February 14, 2014 propositional logic.10 Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Lukasiewicz’ Proof System Prove formulas by starting with Prove formulas by starting with axioms and repeatedly applying axioms and repeatedly applying the inference rule. -

Chapter 9: Answers and Comments Step 1 Exercises 1. Simplification. 2. Absorption. 3. See Textbook. 4. Modus Tollens. 5. Modus P

Chapter 9: Answers and Comments Step 1 Exercises 1. Simplification. 2. Absorption. 3. See textbook. 4. Modus Tollens. 5. Modus Ponens. 6. Simplification. 7. X -- A very common student mistake; can't use Simplification unless the major con- nective of the premise is a conjunction. 8. Disjunctive Syllogism. 9. X -- Fallacy of Denying the Antecedent. 10. X 11. Constructive Dilemma. 12. See textbook. 13. Hypothetical Syllogism. 14. Hypothetical Syllogism. 15. Conjunction. 16. See textbook. 17. Addition. 18. Modus Ponens. 19. X -- Fallacy of Affirming the Consequent. 20. Disjunctive Syllogism. 21. X -- not HS, the (D v G) does not match (D v C). This is deliberate to make sure you don't just focus on generalities, and make sure the entire form fits. 22. Constructive Dilemma. 23. See textbook. 24. Simplification. 25. Modus Ponens. 26. Modus Tollens. 27. See textbook. 28. Disjunctive Syllogism. 29. Modus Ponens. 30. Disjunctive Syllogism. Step 2 Exercises #1 1 Z A 2. (Z v B) C / Z C 3. Z (1)Simp. 4. Z v B (3) Add. 5. C (2)(4)MP 6. Z C (3)(5) Conj. For line 4 it is easy to get locked into line 2 and strategy 1. But they do not work. #2 1. K (B v I) 2. K 3. ~B 4. I (~T N) 5. N T / ~N 6. B v I (1)(2) MP 7. I (6)(3) DS 8. ~T N (4)(7) MP 9. ~T (8) Simp. 10. ~N (5)(9) MT #3 See textbook. #4 1. H I 2. I J 3. -

Argument Forms and Fallacies

6.6 Common Argument Forms and Fallacies 1. Common Valid Argument Forms: In the previous section (6.4), we learned how to determine whether or not an argument is valid using truth tables. There are certain forms of valid and invalid argument that are extremely common. If we memorize some of these common argument forms, it will save us time because we will be able to immediately recognize whether or not certain arguments are valid or invalid without having to draw out a truth table. Let’s begin: 1. Disjunctive Syllogism: The following argument is valid: “The coin is either in my right hand or my left hand. It’s not in my right hand. So, it must be in my left hand.” Let “R”=”The coin is in my right hand” and let “L”=”The coin is in my left hand”. The argument in symbolic form is this: R ˅ L ~R __________________________________________________ L Any argument with the form just stated is valid. This form of argument is called a disjunctive syllogism. Basically, the argument gives you two options and says that, since one option is FALSE, the other option must be TRUE. 2. Pure Hypothetical Syllogism: The following argument is valid: “If you hit the ball in on this turn, you’ll get a hole in one; and if you get a hole in one you’ll win the game. So, if you hit the ball in on this turn, you’ll win the game.” Let “B”=”You hit the ball in on this turn”, “H”=”You get a hole in one”, and “W”=”you win the game”. -

A Unifying Field in Logics: Neutrosophic Logic. Neutrosophy, Neutrosophic Set, Neutrosophic Probability and Statistics

FLORENTIN SMARANDACHE A UNIFYING FIELD IN LOGICS: NEUTROSOPHIC LOGIC. NEUTROSOPHY, NEUTROSOPHIC SET, NEUTROSOPHIC PROBABILITY AND STATISTICS (fourth edition) NL(A1 A2) = ( T1 ({1}T2) T2 ({1}T1) T1T2 ({1}T1) ({1}T2), I1 ({1}I2) I2 ({1}I1) I1 I2 ({1}I1) ({1} I2), F1 ({1}F2) F2 ({1} F1) F1 F2 ({1}F1) ({1}F2) ). NL(A1 A2) = ( {1}T1T1T2, {1}I1I1I2, {1}F1F1F2 ). NL(A1 A2) = ( ({1}T1T1T2) ({1}T2T1T2), ({1} I1 I1 I2) ({1}I2 I1 I2), ({1}F1F1 F2) ({1}F2F1 F2) ). ISBN 978-1-59973-080-6 American Research Press Rehoboth 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005 FLORENTIN SMARANDACHE A UNIFYING FIELD IN LOGICS: NEUTROSOPHIC LOGIC. NEUTROSOPHY, NEUTROSOPHIC SET, NEUTROSOPHIC PROBABILITY AND STATISTICS (fourth edition) NL(A1 A2) = ( T1 ({1}T2) T2 ({1}T1) T1T2 ({1}T1) ({1}T2), I1 ({1}I2) I2 ({1}I1) I1 I2 ({1}I1) ({1} I2), F1 ({1}F2) F2 ({1} F1) F1 F2 ({1}F1) ({1}F2) ). NL(A1 A2) = ( {1}T1T1T2, {1}I1I1I2, {1}F1F1F2 ). NL(A1 A2) = ( ({1}T1T1T2) ({1}T2T1T2), ({1} I1 I1 I2) ({1}I2 I1 I2), ({1}F1F1 F2) ({1}F2F1 F2) ). ISBN 978-1-59973-080-6 American Research Press Rehoboth 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005 1 Contents: Preface by C. Le: 3 0. Introduction: 9 1. Neutrosophy - a new branch of philosophy: 15 2. Neutrosophic Logic - a unifying field in logics: 90 3. Neutrosophic Set - a unifying field in sets: 125 4. Neutrosophic Probability - a generalization of classical and imprecise probabilities - and Neutrosophic Statistics: 129 5. Addenda: Definitions derived from Neutrosophics: 133 2 Preface to Neutrosophy and Neutrosophic Logic by C. -

The Philosophy of Mathematics: a Study of Indispensability and Inconsistency

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2016 The hiP losophy of Mathematics: A Study of Indispensability and Inconsistency Hannah C. Thornhill Scripps College Recommended Citation Thornhill, Hannah C., "The hiP losophy of Mathematics: A Study of Indispensability and Inconsistency" (2016). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 894. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/894 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Philosophy of Mathematics: A Study of Indispensability and Inconsistency Hannah C.Thornhill March 10, 2016 Submitted to Scripps College in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Mathematics and Philosophy Professor Avnur Professor Karaali Abstract This thesis examines possible philosophies to account for the prac- tice of mathematics, exploring the metaphysical, ontological, and epis- temological outcomes of each possible theory. Through a study of the two most probable ideas, mathematical platonism and fictionalism, I focus on the compelling argument for platonism given by an ap- peal to the sciences. The Indispensability Argument establishes the power of explanation seen in the relationship between mathematics and empirical science. Cases of this explanatory power illustrate how we might have reason to believe in the existence of mathematical en- tities present within our best scientific theories. The second half of this discussion surveys Newtonian Cosmology and other inconsistent theories as they pose issues that have received insignificant attention within the philosophy of mathematics. -

CHAPTER 8 Hilbert Proof Systems, Formal Proofs, Deduction Theorem

CHAPTER 8 Hilbert Proof Systems, Formal Proofs, Deduction Theorem The Hilbert proof systems are systems based on a language with implication and contain a Modus Ponens rule as a rule of inference. They are usually called Hilbert style formalizations. We will call them here Hilbert style proof systems, or Hilbert systems, for short. Modus Ponens is probably the oldest of all known rules of inference as it was already known to the Stoics (3rd century B.C.). It is also considered as the most "natural" to our intuitive thinking and the proof systems containing it as the inference rule play a special role in logic. The Hilbert proof systems put major emphasis on logical axioms, keeping the rules of inference to minimum, often in propositional case, admitting only Modus Ponens, as the sole inference rule. 1 Hilbert System H1 Hilbert proof system H1 is a simple proof system based on a language with implication as the only connective, with two axioms (axiom schemas) which characterize the implication, and with Modus Ponens as a sole rule of inference. We de¯ne H1 as follows. H1 = ( Lf)g; F fA1;A2g MP ) (1) where A1;A2 are axioms of the system, MP is its rule of inference, called Modus Ponens, de¯ned as follows: A1 (A ) (B ) A)); A2 ((A ) (B ) C)) ) ((A ) B) ) (A ) C))); MP A ;(A ) B) (MP ) ; B 1 and A; B; C are any formulas of the propositional language Lf)g. Finding formal proofs in this system requires some ingenuity. Let's construct, as an example, the formal proof of such a simple formula as A ) A. -

Proposi'onal Logic Proofs Proof Method #1: Truth Table Example

9/9/14 Proposi'onal Logic Proofs • An argument is a sequence of proposi'ons: Inference Rules ² Premises (Axioms) are the first n proposi'ons (Rosen, Section 1.5) ² Conclusion is the final proposi'on. p p ... p q TOPICS • An argument is valid if is a ( 1 ∧ 2 ∧ ∧ n ) → tautology, given that pi are the premises • Logic Proofs (axioms) and q is the conclusion. ² via Truth Tables € ² via Inference Rules 2 Proof Method #1: Truth Table Example Proof By Truth Table s = ((p v q) ∧ (¬p v r)) → (q v r) n If the conclusion is true in the truth table whenever the premises are true, it is p q r ¬p p v q ¬p v r q v r (p v q)∧ (¬p v r) s proved 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 n Warning: when the premises are false, the 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 conclusion my be true or false 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 n Problem: given n propositions, the truth 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 n table has 2 rows 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 n Proof by truth table quickly becomes 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 infeasible 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 3 4 1 9/9/14 Proof Method #2: Rules of Inference Inference proper'es n A rule of inference is a pre-proved relaon: n Inference rules are truth preserving any 'me the leJ hand side (LHS) is true, the n If the LHS is true, so is the RHS right hand side (RHS) is also true.