Case 1:12-Md-02409-WGY Document 95 Filed 01/22/13 Page 1 of 64

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case 1:06-Cv-01134-RCL Document 27 Filed 07/12/06 Page 1 of 10

Case 1:06-cv-01134-RCL Document 27 Filed 07/12/06 Page 1 of 10 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ____________________________________ SANDOZ, INC. , ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 06-1134 (RCL) ) FOOD AND DRUG ) ADMINISTRATION, et. al.,) ) Defendants. ) ____________________________________) MEMORANDUM OPINION This matter comes before the Court on the plaintiff’s motion [4] for a preliminary injunction. Upon consideration of plaintiff’s motion, the opposition thereto, plaintiff’s reply, the arguments of counsel, the applicable law, and the record in this case, the Court finds that plaintiff’s motion for preliminary injunction should be DENIED. BACKGROUND Congress established the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 to lower the regulatory barriers facing generic drug companies and to encourage those companies to challenge the patents blocking generic entry to the market. See, e.g., Andrx Pharms., Inc. v. Biovail Corp., 276 F.3d 1368, 1371 (Fed. Cir. 2002). In order to encourage generic drug companies to undertake the substantial cost of identifying patents to challenge and bearing the accompanying risks of potential patent litigation, Congress created a critical incentive to reward the first generic manufacturer to file a certification pursuant to 21 U.S.C. § 355(j)(2)(A)(vii)(IV) (a “Paragraph 1 Case 1:06-cv-01134-RCL Document 27 Filed 07/12/06 Page 2 of 10 IV certification”)1 challenging a pharmaceutical patent—namely, a 180 day period of exclusivity during which no other generic version of the drug can be approved. See 21 U.S.C. § 355(j)(5)(B)(iv) (2002); 21 C.F.R. -

Transfer of Technology for Successful Integration Into the Global Economy

UNCTAD/ITE/IPC/Misc.22 Transfer of Technology for Successful Integration into the Global Economy A Case Study of the Pharmaceutical Industry in India Biswajit Dhar and C. Niranjan Rao, with inputs by Veena Gupta United Nations New York and Geneva 2002 Transfer of Technology Note This paper is part of the series of case studies on Transfer of Technology for Successful Integration into the Global Economy carried out by the Investment Policy and Capacity Building Branch, DITE, under the UNCTAD/UNDP Global Programme on Globalization, Liberalization and Sustainable Human Development: Best Practices in Transfer of Technology. The work has been carried out under the direction of Assad Omer, assisted by Maria Susana Arano. Overall guidance was provided by Khalil Hamdani. The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily represent those of UNCTAD or UNDP. UNCTAD/ITE/IPC/MISC. 22 ii Transfer of Technology TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ………………………………………………………………………. vii Introduction.........................................................................................………. ix Chapter I: Historical overview of the Indian pharmaceutical industry 1 1. The policy regime since the 1970s…………………………………… 2 2. The new drug policy of 1978 2 A. Expansion of capabilities and the role of foreign firms……… 2 B. Emphasis on technology and R&D…………………………… 3 C. Price control regime…………………………………………. 4 3. Modifications to the drug policy……………………………………... 5 4. The Indian patent system..……………………………………………. 6 Chapter II: Impact of the policy regime on the development of the pharmaceutical industry.…………………………………………. 9 1. The effects of active policy intervention……………………………… 9 2. Performance of the pharmaceutical industry during the 1990s.........…. 14 A. Production…………………………………………………….. 15 B. Exports………………………………………………………… 16 C. Imports………………………………………………………… 19 D. Research and development……………………………………. -

Focused on Today... Poised for Tomorrow... V

Plot No.90,Sector32,Gurgaon– 122001,Haryana(India) Tel.: +91-124-4135000.Fax:+91-124-4135001 www.ranbaxy.com Edited & Published by Global Corporate Communications at Ranbaxy; Concept & Design by United Advertising; Photography by Aditya Arya; Printed by Thomson Press . w o r r o m o t r o f d e s i o P . y a d o t n o d e s u c o F 7 0 0 2 t r o p e R l a u n n A F ocused ontoda y ... P oised f or tomor r ow ... Annual R e por t 2007 Emerging markets, niche and specialty segments, First-to-File (FTF) products in the US, the NDDR de-merger...indeed, there's a lot new on Ranbaxy's horizon this year. And while change is already underway, this is just the beginning, with several new initiatives lined up for the immediate future. As your Company pushes the frontiers of possibility, both horizontally and vertically, growth through scientific breakthroughs and strategic initiatives is just around the corner. The clear aspiration is to achieve global sales of US $ 5 Bn by 2012 and position Ranbaxy among the top 5 global generic companies. Focused on Today... Poised for Tomorrow... It is indeed a pleasant surprise when you discover something valuable and priceless in something as ordinary as an Oyster. But at Ranbaxy, we have always sensed it was there. The 'Pearl of Success' veiled beyond sight in markets yet untapped and in those wonderfully elusive niche areas, untouched. It took dogged pursuit, and an uncanny sense for business to unravel the marvel and prize it open, discovering along the way, the joys of first mover advantage. -

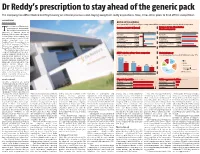

Dr Reddy's Prescription to Stay Ahead of the Generic Pack

Dr Reddy’s prescription to stay ahead of the generic pack The company has differentiated itself by focusing on internal processes and staying away from costly acquisitions. Now, it has other plans to fend off the competition B DASARATH REDDY Hyderabad, 8 August BATTLE OF THE GENERICS As the patent cliff in the US levels off, generic drug makers will face increasing pressure to develop other kinds of products he revenues of Hyderabad- Revenues in 2011-12 (Actual) Revenue for top-three Indian based generic drug maker, Pharma companies T Dr Reddy's Laboratories, is expected to surpass those of ~ crore Revenue Net profit ~ crore 2012-13 2013-14* Ranbaxy Laboratories, the largest Ranbaxy 9,977 Ranbaxy 11,309 Indian generic drug company, and Laboratories* -2,900 Laboratories 12,615 now a subsidiary of Japan’s Daiichi Dr Reddy's 9,674 Dr Reddy's 11,286 Sankyo, sometime next year. Laboratories** 1,426 Laboratories 12,663 Barclays Equity Research projects 8,006 9,694 Dr Reddy’s revenues for FY14 at Sun Pharmaceutical Sun Pharmaceutical 2,587 11,472 ~12,663 crore, slightly higher than Industries** Industries Ranbaxy’s (at ~12,615 crore). *Calendar year 2011, **FY ended March 2012 *Estimates This would be big news for any company battling it out in a chal- ANDA* pipeline of top-three companies Global pharmacy lenging industry. However, the Approved Pending Share of consolidated revenues for Dr Reddy's in the year ‘11-12 generic-drug business is more than just that. It’s a fiercely com- 241 petitive business, driven by vol- umes and characterised by con- 148 148 stantly falling prices and, 101 therefore, steep margins. -

Atorvastatin Calcium ANDA 76477

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Food and Drug Administration Rockville, MD 20857 ANDA 076477 Ranbaxy Inc. U.S. Agent for: Ranbaxy Laboratories Limited Attention: Scott D. Tomsky Senior Manager, Regulatory Affairs 600 College Road East Princeton, NJ 08540 Dear Sir: This is in reference to your abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) dated August 19, 2002, submitted pursuant to section 505(j) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (the Act), for Atorvastatin Calcium Tablets, 10 mg (base), 20 mg (base), 40 mg (base), and 80 mg (base). Reference is also made to your amendments dated December 4, and December 9, 2009; November 12, and November 16, 2010; and June 2, June 3, June 7, July 18, July 25, July 27, August 26, September 1, September 19, and October 5, 2011. We have completed the review of this ANDA and have concluded that adequate information has been presented to demonstrate that the drug is safe and effective for use as recommended in the submitted labeling. Accordingly the ANDA is approved, effective on the date of this letter. The Division of Bioequivalence has determined your Atorvastatin Calcium Tablets, 10 mg (base), 20 mg (base), 40 mg (base), and 80 mg (base), to be bioequivalent and, therefore, therapeutically equivalent to the reference listed drug (RLD), Lipitor Tablets, 10 mg (base), 20 mg (base), 40 mg (base), and 80 mg (base), respectively, of Pfizer, Inc. (Pfizer). Your dissolution testing should be incorporated into the stability and quality control program using the same method proposed in your ANDA. The RLD upon which you have based your ANDA, Pfizer’s Lipitor Tablets, is subject to periods of patent protection. -

Global Strategy for Growth: a Case of Ranbaxy Laboratories

Journal of Case Research Volume II Issue 01 Global Strategy for Growth: A Case of Ranbaxy Laboratories Padmanabha Ramachandra Bhatt1 “Personally, I feel that companies who constantly innovate to provide better products and services and who can offer superior value propositions to the consumer are the ones likely to command more respect globally than others”2 Malvinder Mohan Singh, CEO and MD, Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd Indian pharmaceutical industry was worth of $ 8 billion in 2006 and had been growing at an average rate of 8–9 %. The industry was highly fragmented with more than 20,000 registered units and 30% of market was controlled by top ten companies and the rest of 70% by small companies. The Global pharmaceutical industry was estimated at $ 600 billion in 2006. Indian pharmaceutical industry has become more innovative and enterprising with more investment in R&D especially since the WTO agreement was signed. Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd. was India’s largest pharmaceutical company with revenue of US $ 260 million in the domestic market and $ 1.3 billion in the global market in 2006. In the domestic market Ranbaxy enjoyed a share of 5.1% with nine brands in the Top 100 list in 2006. It is one of the largest ANDA (Abbreviated New Drug Application) filers with US FDA ( United States Food and Drug Administration). The company’s offices have spread over 49 countries with employment of 12,000. It is one of the ten generics players in the world. Three-forth of Ranbaxy’s revenue comes from international sales, with the US alone accounting for almost one third. -

Ranbaxy Reconstitutes Board of Directors Following Strategic Alliance with Japan’S Daiichi Sankyo

19 December 2008, Tokyo and Gurgaon Ranbaxy Reconstitutes Board of Directors following Strategic Alliance with Japan’s Daiichi Sankyo Ranbaxy CEO and Managing Director Malvinder Mohan Singh Takes Additional Role as Chairman of the Board December 19, 2008, Tokyo and Gurgaon – Daiichi Sankyo Company Limited (TSE: 4568.JP) (“Daiichi Sankyo”) and Ranbaxy Laboratories Limited (NSE/BSE: Ranbaxy/500359) (“Ranbaxy”) today announced the reconstitution of Ranbaxy’s Board of Directors. The reconstitution was approved by Ranbaxy’s Board of Directors at a meeting held today at the Company’s headquarters in Gurgaon, India. The composition of the new Board reflects the new ownership structure at Ranbaxy, India’s largest pharmaceuticals company, following Daiichi Sankyo’s strategic investment completed in November 2008. Daiichi Sankyo now holds 63.92% of the equity share capital of Ranbaxy. The reconstituted Board is dedicated to realizing the benefits of the global partnership between Daiichi Sankyo and Ranbaxy in the creation and provision of innovative pharmaceutical products that enrich the quality of human life. Mr. Malvinder Mohan Singh, CEO & MD, additionally assumes the role of Chairman of the Board of Directors. Ranbaxy will maintain its status as a publicly listed company and will continue to operate as an independent and autonomous entity. Underlining Daiichi Sankyo’s strong commitment to the partnership, Ranbaxy’s Board now includes Mr. Takashi Shoda, President & CEO of Daiichi Sankyo. Mr. Shoda, commented: "These appointments signify both companies’ absolute commitment to driving success for this strategic alliance. I am confident that with the leadership team we now have in place, Ranbaxy will swiftly make a significant contribution to the Daiichi Sankyo Group. -

Compulsory Licensing in Pharmaceuticals India

Twenty Years of TRIPS Agreement: What Difference Did Product Patent Protection Make to the Pharmaceutical Industry in India? Sudip Chaudhuri Indian Institute of Management Calcutta International Workshop on the Impact of the TRIPS Agreement on Key Sectors and its Continuing Relevance in the Context of Regional and Bilateral Trading Agreements Centre for WTO Studies, IIFT, New Delhi, 26 and 27 October, 2015 Outline of Presentation • Present some evidence on what has happened after TRIPS in India in pharmaceuticals • Analyse how these statistics may change if product patent protection is again abolished in India • Raise the question of desirability of limiting product patent protection in developing countries Price of MNC monopoly drugs in India, 2013: Examples Price per MOLECULE BRAND MNC GROUP unit in Rs Jevtana 60 Mg Injection Cabazitaxel Sanofi-Aventis Anti-neoplastics 330000 Herceptin Injection 50 Ml Trastuzumab Roche Anti-neoplastics 110700 Erbitux 500 Mg Injection 50 Ml Cetuximab Merck Ltd Anti-neoplastics 92316 Mabthera 500 Mg Injection 50 Ml Rituximab Roche Anti-neoplastics 80000 Novoseven (Eptaccog Alfa) 2.4 Mg Injection 1 Factors Ii, Vii, Ix And X Novo Nordisk India Blood Related 79000 Torisel 25 Mg Injection 1 Ml Temsirolimus Pfizer Ltd Anti-neoplastics 74520 Alimta 500 Mg Eli Lilly and Company Injection 1 Pemetrexed (India) Anti-neoplastics 73660 Sandostatin 0.1 Mg Injection 1 Octreotide Novartis India Blood Related 72081 Ixempra 45 Mg Injection 1 Ixabepilone BMS India Anti-neoplastics 71175 Sandostatin Lar 20 Mg Injection -

2018 Alameda County, California Med-Project Annual Report

2018 ALAMEDA COUNTY, CALIFORNIA MED-PROJECT ANNUAL REPORT Prepared By: MED-Project LLC Submitted To: Alameda County, Department of Environmental Health Date: February 25, 2019; Revised March 22, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................. 3 2. REPORTING ON 2018 GOALS ................................................... 4 2.1. Collection Goals .......................................................................................................... 4 2.2. Education and Public Outreach Goals .................................................................... 8 2.3. Take-Back Events ...................................................................................................... 10 2.4. The Collection System ............................................................................................. 11 3. 2019 GOALS ...........................................................................16 3.1. Take-Back Events ...................................................................................................... 16 3.2. Kiosk Drop-Off Sites ................................................................................................ 16 3.3. Education and Public Outreach.............................................................................. 16 4. COLLECTION PRACTICES ........................................................18 5. EDUCATIONAL EFFORTS AND PUBLIC OUTREACH ...................19 6. SAFETY AND SECURITY REPORT .............................................24 -

For Immediate Release Company Name: DAIICHI SANKYO

For Immediate Release Company name: DAIICHI SANKYO COMPANY, LIMITED Representative: Joji Nakayama, President and CEO (Code no.: 4568, First Section of Tokyo, Osaka and Nagoya Stock Exchanges) Please address inquiries to Toshiaki Sai, Corporate Officer, Vice President, Corporate Communications Department Telephone: +81-3-6225-1126 http://www.daiichisankyo.com/ RANBAXY ANNOUNCES LAUNCH OF ATORVASTATIN, GENERIC LIPITOR®, IN THE U.S. Attached is the press release by Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd., a subsidiary of Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., which was issued on December 1, 2011. RANBAXY ANNOUNCES LAUNCH OF ATORVASTATIN, GENERIC LIPITOR®, IN THE U.S. Princeton, New Jersey, USA and Gurgaon, India, December 1, 2011 – Ranbaxy Pharmaceuticals Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd. (RLL, NSE: RANBAXY, BSE: 500359) (“Ranbaxy”), today announced that it has received final approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to manufacture and market Atorvastatin and has launched the product in the U.S. market. Atorvastatin is a cholesterol‐reducing medicine, the generic equivalent of the brand Lipitor®, which generated total annual sales of $7.89 billion in the United States through September 2011.1 Mr. Arun Sawhney, CEO & Managing Director, Ranbaxy, stated, “Atorvastatin helps millions of Americans manage healthy cholesterol levels, and we are pleased to have received FDA approval to manufacture and market a safe, effective, affordable and accessible alternative to branded Lipitor. We are committed to continuing to expand our portfolio of products offered in the U.S. market for the benefit of patients, prescribers and the U.S. healthcare system.” Pursuant to an agreement between Ranbaxy and Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. -

FDA AIP Letter to Ranbaxy Laboratories

Public Health Service DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Food and Drug Administration Memorandum February 25, 2009 Mr. Malvinder Mohan Singh CEO & Managing Director Ranbaxy Laboratories Limited Corporate Office Plot 90; Sector 32 Gurgaon - 122001 (Haryana) India Dear Mr. Singh: The Center for Drug Evaluation and Research has determined that Ranbaxy Laboratories Limited (Ranbaxy) submitted untrue statements of material fact in abbreviated and new drug applications filed with the Agency. These findings concern the submission of information, such as from stability test results in support of pending and approved drug applications, from the Ranbaxy Laboratories Limited site located at Paonta Sahib, Sirmour District, Himachal Pradesh, India, (herein referred to as the “Paonta Sahib site”). The following are examples of the observations that support our conclusion that Ranbaxy submitted untrue statements of material fact in drug applications filed with the Agency: 1. Ranbaxy submitted stability information in numerous approved and pending applications that contain untrue statements of material fact, because Ranbaxy failed to include critical information about the storage and testing of the product. During a February 2006 inspection of the Paonta Sahib manufacturing facility, FDA found that hundreds of stability samples, many of which were being used for room temperature or accelerated stability studies, were being stored in refrigerators at (b) (b) (4) approximately (4) between the time they were removed from their stability ( chamber and the time they were tested. Among other things, FDA investigators found that the sample logbooks did not identify the samples that were being held in the refrigerators, their storage duration in the refrigerators, and the justification for this storage. -

Ranbaxy Laboratories Raided by US Officials

www.asiabiotech.com Industry Watch India Ranbaxy Laboratories by US Officials ndian pharmaceutical company, Ranbaxy Laboratories said that the US officials had raided its American corporate offices in Princeton, New Jersey. Raghu Kochar, head Iof corporate communications for the company in India, confirmed that US officials had searched Ranbaxy’s American facilities and promised that the company would cooperate fully. But Kochar declined to say whether Ranbaxy was aware of the reason for the search or any investigation that may have prompted it, referring to a company statement that the search had come “as a surprise” and that Ranbaxy was not aware of any wrongdoing. Charles Caprariello, a spokesman for the Ranbaxy US affiliate, said officials of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had conducted a broad search of the premises “and took a variety of documents.” “It’s been a wide dragnet — a sweep of questions — and we’ve tried to work with them in answering everything they’ve asked,” Caprariello said. A spokeswoman for the Food and Drug Administration, Catherine McDermott, said the agency could not “confirm or deny FDA involvement” in the Ranbaxy case, referring calls to the Department of Justice. A spokeswoman for the federal prosecutor’s office in Maryland — where the agency has its headquarters — said the office could not comment on pending investigations. Ranbaxy, the top Indian drug maker by sales, reported net profit of US$42 million for the October-December quarter. Its sales in the United States, where the company introduced 10 new products last year, rose 16 percent during the quarter.