Final Report of the Blue Ribbon Commission on Jury System Improvement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Professor Mark Compton Recognised with the Order of St John’S Highest Honour, Bailiff Grand Cross, at Kensington Palace

spotlite National news from the Australian Office of St John Ambulance Australia BEST PRACTICE | SHARED SERVICES #1 2018 PROFESSOR MARK COMPTON RECOGNISED WITH THE ORDER OF ST JOHN’S HIGHEST HONOUR, BAILIFF GRAND CROSS, AT KENSINGTON PALACE St John Ambulance Australia is delighted to announce that Chancellor of the Order of St John in Australia and Chairman of the National Board of Directors of St John Ambulance Australia, Professor Mark Compton AM GCStJ, has been recognised by being promoted to Bailiff Grand Cross, the highest grade in the Order of St John. Professor Compton is the 5th Australian Priory member to hold this grade, joining Major General (Professor) John Pearn AM RFD (Ret’d) GCStJ, Dr Neil Conn AO GCStJ, John Spencer AM GCStJ and Professor Villis Marshall AC GCStJ. There are only 21 persons in the world who hold this honour. Professor Compton was invested by the Grand Prior of the Order, His Royal Highness, Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester at Kensington Palace, London on Thursday the 1st of February 2018. “I am honoured and humbled by my appointment to Bailiff Grand Cross. It came as a great surprise. I’ve been so proud to be a member of St John for almost 45 years. Voluntary service is so important to the strong fabric of the Australian community and it is something that is in my blood, with 4 generations of family being St John members. I firmly believe that first aid is one of the most valuable life skills that can be taught,” said Professor Compton. “I cannot think of anyone more deserving of this promotion,” said Len Fiori, CEO of St John Ambulance Australia. -

December 2014

The Bulletin Order of St. John of Jerusalem, Knights Hospitaller Under the Constitution of the Late King Peter II of Yugoslavia Russian Grand Priory of Malta ‘The Malta Priory’ R. Nos.52875-528576 No. 120-2014 Special Edition - 50th Anniversary Order of St. John of Jerusalem, Knights Hospitaller Russian Grand Priory of Malta ‘Palazzino Sapienti’, 223 St. Paul Street, Valletta VLT 1217 Malta. Telephone: +356 2123 0712 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.maltaknights.org TheLieutenant Grand Master of the Order H.E. Bailiff Michel Bohé OSJ, CMSJ Noteworthy memories of the past have, on the 8th of March 2014, made my visit to Malta a pleasurable and yet sentimental visit purposely made to celebrate, with the members of the Malta Priory, the 50th anniversary of the inauguration of ‘The Malta Priory’. Throughout these past fifty years, the Malta Priory has under- gone great changes - some good but others painful to the extent that schisms started to take place right after the death of King Peter. The main and most important change was when The Malta Priory was elevated, in February 22, 1970, to a Grand Priory to be known as the Russian Grand Priory of Malta. and to become the mother and the base of the Order as it stands today. From the many schisms that had occurred, a fortunate and positive move took place in April 2006 when, by the signing of a Concordat, a number of Priories joined the Russian Grand Priory of Malta to return back within their home base and International Headquarters in Malta. -

RUSSIAN TRADITION of the KNIGHTS of MALTA OSJ The

RUSSIAN TRADITION OF THE KNIGHTS OF MALTA OSJ The Russian tradition of the Knights Hospitaller is a collection of charitable organisations claiming continuity with the Russian Orthodox grand priory of the Order of Saint John. Their distinction emerged when the Mediterranean stronghold of Malta was captured by Napoleon in 1798 when he made his expedition to Egypt. As a ruse, Napoleon asked for safe harbor to resupply his ships, and then turned against his hosts once safely inside Valletta. Grand Master Ferdinand von Hompesch failed to anticipate or prepare for this threat, provided no effective leadership, and readily capitulated to Napoleon. This was a terrible affront to most of the Knights desiring to defend their stronghold and sovereignty. The Order continued to exist in a diminished form and negotiated with European governments for a return to power. The Emperor of Russia gave the largest number of Knights shelter in St Petersburg and this gave rise to the Russian tradition of the Knights Hospitaller and recognition within the Russian Imperial Orders. In gratitude the Knights declared Ferdinand von Hompesch deposed and Emperor Paul I was elected as the new Grand Master. Origin Blessed Gerard created the Order of St John of Jerusalem as a distinctive Order from the previous Benedictine establishment of Hospitallers (Госпитальеры). It provided medical care and protection for pilgrims visiting Jerusalem. After the success of the First Crusade, it became an independent monastic order, and then as circumstances demanded grafted on a military identity, to become an Order of knighthood. The Grand Priory of the Order moved to Rhodes in 1312, where it ruled as a sovereign power, then to Malta in 1530 as a sovereign/vassal power. -

The Rules of the Sovereign Order 2012

SOVEREIGN ORDER OF ST. JOHN OF JERUSALEM, KNIGHTS HOSPITALLER THE RULES OF THE SOVEREIGN ORDER 2012 Under The Constitution of H.M. King Peter II of 1964 And including references RULES TABLE OF CONTENTS I NAME, TRADITION [Const. Art. 1] 4 II PURPOSE [Const. Art 2] 6 III` LEGAL STATUS [Const. Art. 3] 7 IV FINANCE [Const. Art. 4] 10 V HEREDITARY PROTECTOR & HEREDITARY KNIGHTS [Const. Art.5] 11 VI GOVERNMENT 12 A. GRAND MASTER [Const. Art 10] B. SOVEREIGN COUNCIL [Const. Art. 7] C. PETIT CONSEIL [Const. Art. 8] D. COURTS OF THE ORDER [Const. Art. 9] VII THE PROVINCES OF THE ORDER [Const. Art. 11] 33 A. GRAND PRIORIES [Const. Art. 11.5] B. PRIORIES [Const. Art. 11.2] C. COMMANDERIES VIII MEMBERSHIIP [Const. Art. 12 as amended] 41 A. INVESTITURE B. KNIGHTS & DAMES [Const. Art. 12 & 14] C. CLERGY OF THE ORDER [Const. Art. 13] ECCLESIASTICAL COUNCIL D. SQUIRES, DEMOISELLES, DONATS, SERVING BROTHERS & SISTERS OF THE ORDER [Cont. Art. 15] IX RANKS, TITLES & AWARDS [Const. Art. 12] 50 A. RANKS B. TITLES C. AWARDS X REGALIA & INSIGNIA [Const. Art. 3] 57 A. REGALIA B. INSIGNIA RULE LOCATION PAGE RULE LOCATION PAGE ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURES APPENDIX 12 106 AGE LIMITS RANKS, TITLES & AWARDS 54 AIMS NAME, TRADITION 4 AMENDMENT GOVERNMENT 13 AMENDMENTS OF KKPII CONSTITUTION APPENDIX 15 115 ANNUAL REPORT FINANCE 10 ARMS OF THE ORDER REGALIA & INSIGNIA 58 ASPIRANT MEMBERSHIP 43 AUDITORS FINANCE 10 AUDIT COMMITTEE OF SOVEREIGN COUNCIL GOVERNMENT 24 AUXILIARY JUDGE GOVERNMENT 30 BADGE REGALIA & INSIGNIA 58 BAILIFF RANKS, TITLES, AWARDS 51 BAILIFF EMERITUS RANKS, TITLES, AWARDS 53 BALLOT GOVERNMENT 14 1 Page RULE LOCATION PAGE BEATITUDES MEMBERSHIP—INVESTITURE 46 BY-LAWS FOR TAX-FREE CORPORATE STATUS LEGAL STATUS 7 CAPE REGALIA & INSIGNIA 57 CERTIFICATE OF MERIT RANKS, TITLES, AWARDS 55 CHAINS OF OFFICE REGALIA, TITLES, AWARDS 58 CHAPLAIN PROVINCES OF THE ORDER 34 CHAPTER GENERAL PROVINCES OF THE ORDER 33 CHARITABLE STATUS LEGAL STATUS 7 CHARITABLE WORK PURPOSE 6 CHARTER APPENDIX 60 CHARTER OF ALLIANCE LEGAL STATUS 9 CHIVALRY NAME, TRADITION 4 CHIVALRIC ORDER VS. -

The Hospitaller

THE HOSPITALLER A Publication of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem—Knights Hospitaller HM King Peter II Constitution—Grand Master HRH Prince Karl Vladimir Karadjordjevic of Yugoslavia GCSJ Volume 1 Issue 1 July 2014 Editor: H.E. Conventual Bailiff Grand Master’s Serbian Flood Appeal Fred Maestrelli GCSJ OMSJ Grand Hospitaller P.O. Box 192 Penshurst NSW 2222 AUSTRALIA “We would like to thank all those wonderful people who have donated to this appeal up to now and we very much hope with all our WIFE & HUSBAND OF hearts that we are able to reach our target THE GRAND PRIORY before too long. OF AUSTRALASIA AWARDED MEDALS The situation in Serbia and Bosnia- Herzegovina has stabilised in relation to the The Grand Master has rain but the current receding of the waters been pleased to bestow has only gone to bring new problems as the Cross of Merit on well as make the damage all that more the Grand Chancellor, clear! HE Conventual Bailiff We will continue to serve the most urgent Shane Hough GCSJ cases as best we can and look forward to OMSJ. The Grand Mas- HRH Prince Karl Vladimir doing more as new donations come in. Karadjordjevic of Yugoslavia GCSJ ter has also been Once again, thank you so very much! pleased to bestow the Cross of Merit with Crown on Dame Vladimir and Brigitta Karadjordjevic” Sallyanne Hough DCSJ Donations are still urgently needed and can be made by visiting this web page. CMSJ. The medals and diplomas will be pre- sented in London in July http://www.gofundme.com/993b3c Editor 2014. -

September, 2015

Sovereign Order of St. John of Jerusalem Knights Hospitaller Special Edition Welcome to this Special Edition of the International Newsletter covering the 2014 Sovereign Council meetings, Investiture and other events in Malta and the subsequent tour of Sicily and mainland Italy. MALTA MEETINGS AND EVENTS More than 220 members and guests of the Sovereign Order participated in Sovereign Council meetings, a memorable Investiture and other events in sunny, hot and welcoming Malta. Malta has a known history of over 7,000 years and all visitors enjoyed exploring this ancient and modern Island. The capital city, Valetta was founded by Grand Master La Valette of the Order of St. John ”the gallant hero of the Great Siege of 1565.” Valetta is the smallest of European capital cities and is a world heritage site. We welcomed members and guests of the Order from Austria, Canada, Denmark, England, Finland, France, Germany, Monaco, Nicaragua, Norway, Scotland and the United States of America. SOVEREIGN COUNCIL AND OTHER MEETINGS The Sovereign Council held its biennial meeting on September 22 and 23. In addition to discussing the business of the Order, the meeting also discussed other matters relating to the Order and its future. Due to age the limit of 80 for being a Bailiff, the following members of the Sovereign Council retired at the meeting: HE Conventual Bailiff Grand Conservator René Tonna-Barthet, GCSJ, CMSJ and two Bars, MMSJ, (England). René has been a member of the Order since 1964. In recognition of his very significant contributions to the Order René was awarded the Gold Cross of Merit. -

E-Newsletter

Contents International Numismatic 01 The President’s Note 02 Reports from institutions e-Newsletter 04 Congresses and Meetings 08 Research programs 08 Exhibitions 09 Websites 10 New publications INeN 18 - January 2015 17 Personalia 18 Obituaries 20 INC Annual Travel Grant 21 INeN contribute and suscribe The President’s Note - Il saluto del Presidente Dear INC members, dear colleagues and friends, On behalf of the INC I wish you that in these times of polarization on a multitude of issues all a happy and prosperous about cultural property, we can find common ground and New Year! It is an important collaborate to the benefit of numismatics. year for our Council and for the numismatic community The INC Committee will meet in Taormina in March to at large since it is the year make sure that everything will be ready to welcome you in of our XVth International September and make your participation as productive and Congress, which will take pleasant as possible. I also want to thank the Scientific place in Taormina, September and Organizing Committee for all their work: we are in 21-25, 2015. It is, as you a period of recession and economic instability and the know, the most important financing of this Congress is one of the most challenging event for the INC, and its the INC ever had to face. Governments can no longer organization, as well as the afford to be as generous as Spain was in 2003 and offer Dr. Carmen Arnold-Biucchi publication of the Survey of a spectacular Palace of Congresses for free. -

Epistula Canadian Association of the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St

December 2016 Epistula Canadian Association of the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta IN THIS ISSUE Message from the Past President 2 Message from the New President 3 Message from the Principal Chaplain 4 In Memoriam : Fra’ John Alexander MacPherson 5 Academic Internships in Africa 7 In the Next Issue 9 Pilgrimage at the Canadian Martyr’s Shrine, in Midland On Saturday, 14th October, the Toronto Region organized a mini - pilgrimage to the Canadian Martyr's Shrine in Midland, Ontario, a little more than an hour north of Toronto. This national shrine commemorates the martyrdom of the Jesuit Jean de Brébeuf and his companions in 1649. Despite being closed for the winter, the Director, Father Michael Knox, sj, opened the site for us and guided us through a discussion, mass, a communal meal, and a visit to all parts of the shrine, explaining the meaning and the need for a true commitment to Christ, as well as the history of the original Jesuits at Midland. Very few National Pilgrimage to Lourdes churches can concentrate the mind like the simple clearing in the from May 4 to May 8, 2018 forest at St - Ignace, where the martyrs were tortured and died for their faith and their parishioners. Tuitio Fidei et Obsequium Pauperum Many of us felt this five hour pilgrimage to be as intense and more personal than even Lourdes......and yet many Canadians do not know of it. Definitely a repeat for all concerned ! Vigil and Investiture in Ottawa on September 7 and 8, 2018 1 Message from the Past President THANK YOU ! I am very happy to report that the last Lourdes pilgrimage I leave in the knowledge that the Association is in good was a resounding success. -

Numismatics Fine Art Objects of Vertu Le Méridien Beach Plaza Monaco 17 November 2019

NUMISMATICS FINE ART OBJECTS OF VERTU LE MÉRIDIEN BEACH PLAZA MONACO 17 NOVEMBER 2019 SPECIALISTS AND AUCTION ENQUIRIES Special Partnership HAMPEL Fine Art Auctions Munich Germany Alessandro Conelli Elena Efremova Maria Lorena President Director Franchi Deputy Director Ivan Terny Anna Chouamier Victoria Matyunina Yolanda Lopez Julia Karpova Auctioneer Client Manager PR & Event Manager Administrator Art Director In-house experts Special partnership Hermitage Fine Art expresses its gratitude to expert Rene Millet for help with attribution of the lots 250, 251 and 253. Catalogue Design: Camille Maréchaux Translator and editor : Evgenia Lapshina Sergey Podstanitsky Federico Pastrone Alexandra Gamaliy Arthur Gamaliy Sergey Cherkachin Expert Specially Invited Expert Head of business Specially Invited Text Editor : Manuscripts & Expert and Advisor Numismatics Development and Expert Natasha Cheung rare Bookes Paintings Client Management Russian Art Photography: (Moscow) François Fernandez Luigi Gattinara Maxim Melnikov Contact : Tel: +377 97773980 Fax: +377 97971205 [email protected] PAR LE MINISTERE DE MAITRE CLAIRE NOTARI HUISSIER DE JUSTICE A MONACO NUMISMATICS FINE ART OBJECTS OF VERTU NUMISMATICS SUNDAY NOVEMBER 17, 2019 - 12:00 FINE ART SUNDAY NOVEMBER 17, 2019 - 15:30 OBJECTS OF VERTU SUNDAY NOVEMBER 17, 2019 - 17:30 ROSSICA 2 SUNDAY NOVEMBER 17, 2019 - 18:30 RUSSIAN ART & HISTORY THURSDAY NOVEMBER 21, 2019 - 11:00 ANTIQUARIUM ROADSHOW THURSDAY NOVEMBER 21, 2019 - 17:30 Le Méridien Beach Plaza - 22 Av. Princesse Grace - 98000 MONACO Exhibition Opening : SUNDAY NOVEMBER 17, 2019 - 10:00 PREVIEW DETAILS: information on website www.hermitagefneart.com Inquiries - tel: +377 97773980 - Email: [email protected] 25, Avenue de la Costa - 98000 Monaco Tel: +377 97773980 www.hermitagefneart.com NUMISMATICS Numismatic Books 6 1 • войск и войск связи, С.- BUNIN Narcise Nikolaévitch (1856-1912) Петербург), а также мирные Le grand-duc Georges Mikhaïlovitch de Russie avec son setter будни армии ("Вручение Feldmann. -

Constitution and Code

CONSTITUTIONAL CHARTER AND CODE OF THE SOVEREIGN MILITARY HOSPITALLER ORDER OF ST. JOHN OF JERUSALEM OF RHODES AND OF MALTA Promulgated 27 June 1961 revised by the Extraordinary Chapter General 28-30 April 1997 CONSTITUTIONAL CHARTER AND CODE OF THE SOVEREIGN MILITARY HOSPITALLER ORDER OF ST. JOHN OF JERUSALEM OF RHODES AND OF MALTA Promulgated 27 June 1961 revised by the Extraordinary Chapter General 28-30 April 1997 This free translation is not be intended as a modification of the Italian text approved by the E x t r a o r d i n a ry Chapter General 28-30 April 1997 and pubblished in the Bollettino Uff i c i a l e , 12 January 1 9 9 8 . In cases of diff e r ent interpretations, the off i c i a l Italian text prevails (Art. 36, par. 3 Constitutional C h a r t e r ) . 4 CO N S T I T U T I O N A L C H A RT E R OF THE SOVEREIGN MILITA RY H O S P I TALLER ORDER OF ST. JOHN OF JERUSALEM OF RHODES AND OF MALTA 5 I N D E X Ti t l e I - TH E O R D E R A N D I T S N AT U R E . 19 A rticle 1 Origin and nature of the Order . 19 A rticle 2 P u r p o s e . 10 A rticle 3 S o v e r eignty . 11 A rticle 4 Relations with the Apostolic See . -

Membership Roll

FOR PERSONAL USE ONLY - NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω MEMBERSHIP ROLL Illustrious Royal Order of Saint Januarius Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George Royal Order of Francis I DELEGATION OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND March 2015 The Grand Master HRH Prince Charles of Bourbon Two Sicilies, Duke of Castro, and HRH Princess Camilla of Bourbon Two Sicilies, Duchess of Castro, His Eminence Renato Raffaele, Cardinal Martino, Grand Prior of the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George The Prayer of the Constantinian Order 1 The History of the Order in Great Britain 2 The History of the Order in Ireland 4 Council of the Delegation of Great Britain and Ireland 6 Members of the Delegation of Great Britain and Ireland 8 Illustrious Royal Order of Saint Januarius 8 » In the Category of Knight 8 Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George 9 » In the Category of Justice 9 » In the Special Category 10 » In the Category of Grace 10 » In the Category of Merit 12 » » In the Category of Office 15 RoyalRecepients Order of of BenemerentiFrancis I Medals 1715 Post Nominals of Decorations 20 Obituaries 21 The Prayer of the Constantinian Order Almighty and Merciful Father, King of kings and Lord of lords, in Your immeasurable goodness You have called me into the ranks of the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George, Your Knight and Martyr. May I never cease to emulate our heavenly patron and with alacrity fol- low in the footsteps of Your Only-begotten Son, Who is our Alpha and Omega, our Beginning and End. -

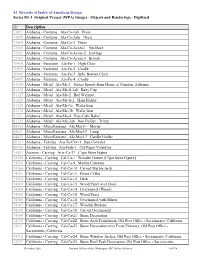

Images - Objects and Renderings - Digitized

44 Records of Index of American Design Series D1-3 Original Project (WPA) Images - Objects and Renderings - Digitized ID Description 73097 Alabama - Costume Ala-Co-1ab Dress 73098 Alabama - Costume Ala-Co-2abc Dress 73099 Alabama - Costume Ala-Co-3 Dress 73100 Alabama - Costume Ala-Co-Acces-1 Necklace 73101 Alabama - Costume Ala-Co-Acces-2 Earrings 73102 Alabama - Costume Ala-Co-Acces-3 Brooch 76904 Alabama - Furniture Ala-Fu-1 High Chair 76905 Alabama - Furniture Ala-Fu-2 Cradle 76906 Alabama - Furniture Ala-Fu-3 Split Bottom Chair 76907 Alabama - Furniture Ala-Fu-4 Cradle 81325 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-1 Gutter Spouts from House at Camden, Alabama 81326 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-S-1ab Baby Cup 81327 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-2 Bed Warmer 81328 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-S-2 Ham Holder 81329 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-3a Wafer Iron 81330 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-3b Wafer Iron 81331 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-4 Hoe-Cake Baker 81332 Alabama - Metal Ala-Me-5ab Iron Holder - Trivet 84450 Alabama - Miscellaneous Ala-Mscl-1 Mortar 84451 Alabama - Miscellaneous Ala-Mscl-2 Lamp 84452 Alabama - Miscellaneous Ala-Mscl-3 Candle Holder 88707 Alabama - Textiles Ala-Te-Cov-1 Bed Coverlet 88708 Alabama - Textiles Ala-Emb-1 Cut Paper Valentine 74357 Arizona - Carving Ariz-Ca-37 Cigar Store Figure 74358 California - Carving Cal-Ca-1 Wooden Hunter [Cigar Store Figure] 74359 California - Carving Cal-Ca-9 Marble Columns 74360 California - Carving Cal-Ca-10 Carved Marble Arch 74361 California - Carving Cal-Ca-11 Horse Collar 74362 California - Carving Cal-Ca-12 Desk 74363 California