The Cea Forum 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iris (Standard)

IRIS (STANDARD) As recorded by Goo Goo Dolls (From the 1998 Album DIZZY UP THE GIRL) Transcribed by zekeyheathy and edited by Words and Music by John Rzeznik Jarryd Conrad V Bm 4 fr. Bmadd9 4 fr. Bm/G D/F Aadd11 4 fr. Bm 5 fr. Bm/A G Dsus2/C 7 fr. Dsus2/B 5 fr. xx xx x x x xb x xx x xx x x x x x xxb x xx A Intro Slow Ballad = 80 Bm P G 1 g I g J }V }V }V }V }V }V }V }V }V }V }V }V VV VV VV VV VV VV VV V} V} V} V} V} VV VV VV VV VV VV VV VV VV VV VV VV V V V V V V V V V V V V Gtr I V} V} V} V} V} V} V} V V V V V T x x x x x x x x x x 0 0 0 0 0 x x x x x 7 7 7 7 7 6 6 6 6 6 4 4 4 4 4 (4) 2 2 2 2 2 A 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 B 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 x x x x x 0 0 0 0 0 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 3 3 3 3 3 (3) 2 2 2 2 2 sl. sl. V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V gg J V V V V V V V V V V V I Gtr II 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 T 10 10 10 8 8 7 7 7 A 7 7 7 9 9 9 7 7 B B 1st Verse D E G Bm Asus4 3 gg 6 V V V I 8 V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V V T V V 7 7 6 4 2 2 A 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 B 5 5 7 7 7 7 0 0 0 0 0 7 5 5 3 2 2 sl. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k1860wx Author Ellis, Sarah Taylor Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies by Sarah Taylor Ellis 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater by Sarah Taylor Ellis Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Sue-Ellen Case, Co-chair Professor Raymond Knapp, Co-chair This dissertation explores queer processes of identification with the genre of musical theater. I examine how song and dance – sites of aesthetic difference within the musical – can warp time and enable marginalized and semi-marginalized fans to imagine different ways of being in the world. Musical numbers can complicate a linear, developmental plot by accelerating and decelerating time, foregrounding repetition and circularity, bringing the past to life and projecting into the future, and physicalizing dreams in a narratively open present. These excesses have the potential to contest naturalized constructions of historical, progressive time, as well as concordant constructions of gender, sexual, and racial identities. While the musical has historically been a rich source of identification for the stereotypical white gay male show queen, this project validates a broad and flexible range of non-normative readings. -

KEVIN COLE “America's Pianist” Kevin Cole Has Delighted

KEVIN COLE “America’s Pianist” Kevin Cole has delighted audiences with a repertoire that includes the best of American Music. Cole’s performances have prompted accolades from some of the foremost critics in America. "A piano genius...he reveals an understanding of harmony, rhythmic complexity and pure show-biz virtuosity that would have had Vladimir Horowitz smiling with envy," wrote critic Andrew Patner. On Cole’s affinity for Gershwin: “When Cole sits down at the piano, you would swear Gershwin himself was at work… Cole stands as the best Gershwin pianist in America today,” Howard Reich, arts critic for the Chicago Tribune. Engagements for Cole include: sold-out performances with the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl; BBC Concert Orchestra at Royal Albert Hall; National Symphony at the Kennedy Center; Hong Kong Philharmonic; San Francisco Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra (London); Boston Philharmonic, Adelaide Symphony Orchestra (Australia) Minnesota Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony, Dallas Symphony, Seattle Symphony,Vietnam National Symphony Orchestra; New Zealand Symphony, Edmonton Symphony (Canada), Ravinia Festival, Wolf Trap, Savannah Music Festival, Castleton Festival, Chautauqua Institute and many others. He made his Carnegie Hall debut with the Albany Symphony in May 2013. He has shared the concert stage with, William Warfield, Sylvia McNair, Lorin Maazel, Brian d’Arcy James, Barbara Cook, Robert Klein, Lucie Arnaz, Maria Friedman, Idina Menzel and friend and mentor Marvin Hamlisch. Kevin was featured soloist for the PBS special, Gershwin at One Symphony Place with the Nashville Symphony. He has written, directed, co- produced and performed multimedia concerts for: The Gershwin’s HERE TO STAY -The Gershwin Experience, PLAY IT AGAIN, MARVIN!-A Celebration of the music of Marvin Hamlisch with Pittsburgh Symphony and Chicago Symphony and YOU’RE THE TOP!-Cole Porter’s 125th Birthday Celebration and I LOVE TO RHYME – An Ira Gershwin Tribute for the Ravinia Festival with Chicago Symphony. -

1 THOMPSON SQUARE Are You Gonna Kiss Me Or Not Stoney

TOP100 OF 2011 1 THOMPSON SQUARE Are You Gonna Kiss Me Or Not Stoney Creek 51 BRAD PAISLEY Anything Like Me Arista 2 JASON ALDEAN & KELLY CLARKSON Don't You Wanna Stay Broken Bow 52 RONNIE DUNN Bleed Red Arista 3 TIM MCGRAW Felt Good On My Lips Curb 53 THOMPSON SQUARE I Got You Stoney Creek 4 BILLY CURRINGTON Let Me Down Easy Mercury 54 CARRIE UNDERWOOD Mama's Song 19/Arista 5 KENNY CHESNEY Somewhere With You BNA 55 SUNNY SWEENEY From A Table Away Republic Nashville 6 SARA EVANS A Little Bit Stronger RCA 56 ERIC CHURCH Homeboy EMI Nashville 7 BLAKE SHELTON Honey Bee Warner Bros./WMN 57 TAYLOR SWIFT Sparks Fly Big Machine 8 THE BAND PERRY You Lie Republic Nashville 58 BILLY CURRINGTON Love Done Gone Mercury 9 MIRANDA LAMBERT Heart Like Mine Columbia 59 DAVID NAIL Let It Rain MCA 10 CHRIS YOUNG Voices RCA 60 MIRANDA LAMBERT Baggage Claim RCA 11 DARIUS RUCKER This Capitol 61 STEVE HOLY Love Don't Run Curb 12 LUKE BRYAN Someone Else Calling... Capitol 62 GEORGE STRAIT The Breath You Take MCA 13 CHRIS YOUNG Tomorrow RCA 63 EASTON CORBIN I Can't Love You Back Mercury 14 JASON ALDEAN Dirt Road Anthem Broken Bow 64 JERROD NIEMANN One More Drinkin' Song Sea Gayle/Arista 15 JAKE OWEN Barefoot Blue Jean Night RCA 65 SUGARLAND Little Miss Mercury 16 JERROD NIEMANN What Do You Want Sea Gayle/Arista 66 JOSH TURNER I Wouldn't Be A Man MCA 17 BLAKE SHELTON Who Are You When I'm.. -

View Song List

Song Artist What's Up 4 Non Blondes You Shook Me All Night Long AC-DC Song of the South Alabama Mountain Music Alabama Piano Man Billy Joel Austin Blake Shelton Like a Rolling Stone Bob Dylan Boots of Spanish Leather Bob Dylan Summer of '69 Bryan Adams Tennessee Whiskey Chris Stapleton Mr. Jones Counting Crows Ants Marching Dave Matthews Dust on the Bottle David Lee Murphy The General Dispatch Drift Away Dobie Gray American Pie Don McClain Castle on the Hill Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Rocket Man Elton John Tiny Dancer Elton John Your Song Elton John Drink In My Hand Eric Church Give Me Back My Hometown Eric Church Springsteen Eric Church Like a Wrecking Ball Eric Church Record Year Eric Church Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton Rock & Roll Eric Hutchinson OK It's Alright With Me Eric Hutchinson Cruise Florida Georgia Line Friends in Low Places Garth Brooks Thunder Rolls Garth Brooks The Dance Garth Brooks Every Storm Runs Out Gary Allan Hey Jealousy Gin Blossoms Slide Goo Goo Dolls Friend of the Devil Grateful Dead Let Her Cry Hootie and the Blowfish Bubble Toes Jack Johnson Flake Jack Johnson Barefoot Bluejean Night Jake Owen Carolina On My Mind James Taylor Fire and Rain James Taylor I Won't Give Up Jason Mraz Margaritaville Jimmy Buffett Leaving on a Jet Plane John Denver All of Me John Legend Jack & Diane John Mellancamp Folsom Prison Blues Johnny Cash Don't Stop Believing Journey Faithfully Journey Walking in Memphis Marc Cohn Sex and Candy Marcy's Playground 3am Matchbox 20 Unwell Matchbox 20 Bright Lights Matchbox 20 You Took The Words Right Out Of Meatloaf All About That Bass Megan Trainor Man In the Mirror Michael Jackson To Be With You Mr. -

Feature Guitar Songbook Series

feature guitar songbook series 1465 Alfred Easy Guitar Play-Along 1484 Beginning Solo Guitar 1504 The Book Series 1480 Boss E-Band Guitar Play-Along 1494 The Decade Series 1464 Easy Guitar Play-Along® Series 1483 Easy Rhythm Guitar Series 1480 Fender G-Dec 3 Play-Along 1497 Giant Guitar Tab Collections 1510 Gig Guides 1495 Guitar Bible Series 1493 Guitar Cheat Sheets 1485 Guitar Chord Songbooks 1494 Guitar Decade Series 1478 Guitar Play-Along DVDs 1511 Guitar Songbooks By Notation 1498 Guitar Tab White Pages 1499 Legendary Guitar Series 1501 Little Black Books 1466 Hal Leonard Guitar Play-Along® 1502 Multiformat Collection 1481 Play Guitar with… 1484 Popular Guitar Hits 1497 Sheet Music 1503 Solo Guitar Library 1500 Tab+: Tab. Tone. Technique 1506 Transcribed Scores 1482 Ultimate Guitar Play-Along Please see the Mixed Folios section of this catalog for more2015 guitar collections. 1464 EASY GUITAR PLAY-ALONG® SERIES The Easy Guitar Play-Along® Series features 9. ROCK streamlined transcriptions of your favorite SONGS FOR songs. Just follow the tab, listen to the CD or BEGINNERS Beautiful Day • Buddy Holly online audio to hear how the guitar should • Everybody Hurts • In sound, and then play along using the back- Bloom • Otherside • The ing tracks. The CD is playable on any CD Rock Show • Use Somebody. player, and is also enhanced to include the Amazing Slowdowner technology so MAC and PC users can adjust the recording to ______00103255 Book/CD Pack .................$14.99 any tempo without changing the pitch! 10. GREEN DAY Basket Case • Boulevard of Broken Dreams • Good 1. -

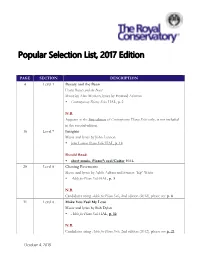

Popular Selection List, 2017 Edition

Popular Selection List, 2017 Edition PAGE SECTION DESCRIPTION 4 Level 1 Beauty and the Beast From Beauty and the Beast Music by Alan Menken; lyrics by Howard Ashman Contemporary Disney Solos HAL, p. 2 N.B. Appears in the first edition of Contemporary Disney Solos only, is not included in the second edition. 18 Level 7 Imagine Music and lyrics by John Lennon John Lennon Piano Solos HAL, p. 18 Should Read: sheet music, Piano/Vocal/Guitar HAL 20 Level 8 Chasing Pavements Music and lyrics by Adele Adkins and Francis “Eg” White Adele for Piano Solo HAL, p. 3 N.B. Candidates using Adele for Piano Solo, 2nd edition (2012), please see p. 8 21 Level 8 Make You Feel My Love Music and lyrics by Bob Dylan Adele for Piano Solo HAL, p. 12 N.B. Candidates using Adele for Piano Solo, 2nd edition (2012), please see p. 21 October 4, 2018 21 Level 8 Someone Like You Music and lyrics by Adele Adkins and Dan Wilson Adele for Piano Solo HAL, p. 30 N.B. Candidates using Adele for Piano Solo, 2nd edition (2012), please see p. 34 21 Level 8 Somewhere From West Side Story Music by Leonard Bernstein; lyrics by Stephen Sondheim West Side Story, Vocal Selections B&H, p. 64 Should Read: West Side Story, Vocal Selections B&H, p. 6 24 Level 9 One and Only Music and lyrics by Adele Adkins, Dan Wilson, and Greg Wells Adele for Solo Piano HAL, p. 15 N.B. Candidates using Adele for Piano Solo, 2nd edition (2012), please see p. -

The Stephen Sondheim Encyclopedia

THE STEPHEN SONDHEIM ENCYCLOPEDIA BY RICK PENDER “A wonderful encyclopedia on all things Sondheim that you will love reading.”— Bernadette Peters, Tony Award- winning actor and star of the original productions of Sunday in the Park with George as Dot and Into the Woods as the Witch “The Stephen Sondheim Encyclopedia is impressive in its depth and detail and a fitting testament to Steve’s extraordinary work. It’s also a lot of fun for any musical theater fan to endlessly peruse.” — James Lapine, playwright and director; bookwriter and director for Sondheim’s Sunday in the Park with George, Into the Woods, and Passion “Anyone who's been touched by Stephen Sondheim's extraordinary body of work will be grateful for this bottomless well of facts, figures, anecdotes and insights. A remarkable and entertaining resource.”— John Weidman, bookwriter for Pacific Overtures, Assassins, and Road Show The Stephen Sondheim Encyclopedia is the first reference volume devoted to the works of this prolific composer and lyricist. The encyclopedia’s entries provide readers with detailed information about Sondheim’s work and key figures in his career, including his apprenticeship with Oscar Hammerstein II, his early work with Leonard Bernstein, and his work on television. Entries include all of his major works and key songs from such musicals as Assassins, Company, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Gypsy, Into the Woods, A Little Night Music, Sunday in the Park with George, Sweeney Todd, and West Side Story. Additional entries focus on his key collaborators, from lyricists to directors. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Rick Pender has been an award-winning theater critic since 1986. -

Lowdermilk Scholarship Winners

Sex With Ron and Sandy Pg. 2 Illegal Immigrants Pg. 5 Sports Briefs Pg. 13 April 6, 2006 Fayetteville, North Carolina Volume 45, Issue 13 Methodist College vs. Barton Left isCollege Methodist College’s Davis Memorial Library. Photo by Melanie Gibson. Above is Barton College’s Willis N. Hackney Library. Photo courtesy of www.barton.edu. Alcohol Policy General Stats Norma Bradshaw Methodist Barton Methodist Barton The possession or Alcohol is not Staff Writer Enrollment: 2100 Enrollment: 1150 consumption of any permitted in the residence Student/Faculty Ratio: 1:15 Student/Faculty Ratio: 1:12 alcoholic beverage is halls at Barton College. Some of the most Cost: $24,620 Cost: $22,550 prohibited on the Empty cans and/or bottles, common complaints from Visitation Policy continued on page 3 see BARTON Methodist College students Barton are the alcohol policy the Methodist The Board of Trustees visitation policy. Let’s see has endorsed residence hall how other schools measure The residence halls visitation in principle and Lowdermilk up. primarily as a social Barton College is are open for visitation from 11:00am to 1:00 am activity. The Board of Scholarship Winners now up, located in Wilson, Trustees authorizes North Carolina. Sunday through Thursday nights and 11:00am to visitation hours in all halls 2:00am Friday and from 9:00 a.m. until Saturday nights. midnight each day and smallTALK No person may have until 2:00 a.m. on Fridays It’s Your Paper more than two guests of and Saturdays, and Opinions ....................... 5 the opposite sex at any delegates, to the Student Life Committee, the Entertainment ........... -

Determining Stephen Sondheim's

“I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS BY ©2011 PETER CHARLES LANDIS PURIN Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy ___________________________ Dr. Deron McGee ___________________________ Dr. Paul Laird ___________________________ Dr. John Staniunas ___________________________ Dr. William Everett Date Defended: August 29, 2011 ii The Dissertation Committee for PETER PURIN Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy Date approved: August 29, 2011 iii Abstract This dissertation offers a music-theoretic analysis of the musical style of Stephen Sondheim, as surveyed through his fourteen musicals that have appeared on Broadway. The analysis begins with dramatic concerns, where musico-dramatic intensity analysis graphs show the relationship between music and drama, and how one may affect the interpretation of events in the other. These graphs also show hierarchical recursion in both music and drama. The focus of the analysis then switches to how Sondheim uses traditional accompaniment schemata, but also stretches the schemata into patterns that are distinctly of his voice; particularly in the use of the waltz in four, developing accompaniment, and emerging meter. Sondheim shows his harmonic voice in how he juxtaposes treble and bass lines, creating diagonal dissonances. -

1999 Prince (I've Had) the Time of My Life Dirty Dancing 3 A.M

Title 1999 Prince (I've Had) the Time of My Life Dirty Dancing 3 a.m. Matchbox 20 A Lot of Lovin' to Do Charles Strouss Bye, Bye Birdie A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton A Whole New World Aladdin Aladdin A Wonderul Guy Rodgers & Hammerstein South Pacific All I Ask of You Andrew Lloyd Webber Phantom of the Opera Duet Another Suitcase in Another Hall Andrew Lloyd Webber Evita Anthem Chess Chess Anything You Can Do Irving Berlin Annie Get Your Gun Duet Apologize One Republic Bad Michael Jackson Bali Hai Rodgers & Hammerstein South Pacific Barnum (Complete Score) Cy Coleman Barnum Beautiful Christina Aguilera Beauty and the Beast Beauty and the Beast Beauty and the Beast Beauty School Dropout Grease Grease Beethoven Day You're a Good Man Charlie Brown You're a Good Man Charlie Brown Before I Gaze at You Again Lerner & Loewe Camelot Believe Cher Bennie & the Jets Elton John Best of Beyonce (Anthology) Beyonce Better Edward Kleban A Class Act Bewtiched Ella Fitzgerald Pal Joey Beyond the Sea Bobby Darin Black Coffee Ella Fitzgerald Blackbird The Beatles Blue Christmas Elvis Presley Blue Moon Elvis Presley Bohemian Rhapsody Queen Bombshell (music from SMASH) Marc Shaiman Bombshell Born this Way Lady Gaga Bosom Buddies Jerry Herman Mame Duet Both Sides Now Joni Mitchell Brand New You Jason Robert Brown 13, the Musical Breeze Off the River The Full Monty The Full Monty Bring Him Home Boublil & Schoenberg Les Miserables Bring On the Men Leslie Bricusse Jekyll & Hyde Broadway Baby Stephen Sondheim Follies Broadway, Here I Come Smash Smash Brown-Eyed -

George Furth

AND Norma and Sol Kugler PRESENT MUSIC & LYRICS BY Stephen Sondheim BOOK BY George Furth STARRING Aaron Tveit AND Jeannette Bayardelle Mara Davi Josh Franklin Ellen Harvey Rebecca Kuznick Kate Loprest James Ludwig Lauren Marcus Jane Pfitsch Zachary Prince Peter Reardon Nora Schell Lawrence E. Street SCENIC DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER SOUND DESIGNER Kristen Robinson Sara Jean Tosetti Brian Tovar Ed Chapman HAIR & WIG DESIGNER PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER CASTING Liz Printz Renee Lutz Pat McCorkle, Katja Zarolinski, CSA BERKSHIRE PRESS REPRESENTATIVE NATIONAL PRESS REPRESENTATIVE Charlie Siedenburg Matt Ross Public Relations MUSIC SUPERVISION BY MUSICAL DIRECTION BY Darren R. Cohen Dan Pardo CHOREOGRAPHED BY Jeffrey Page DIRECTED BY Julianne Boyd Sponsored in part by Carrie and David Schulman COMPANY is presented through a special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). ORIGINALLY PRODUCED AND DIRECTED ON BROADWAY BY Harold Prince ORCHESTRATIONS BY Jonathan Tunick BOYD-QUINSON MAINSTAGE AUGUST 10—SEPTEMBER 10, 2017 TIME & PLACE 1970's New York City, Robert’s 35th birthday. CAST IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE Robert .....................................................................................................Aaron Tveit* Susan ...................................................................................................Kate Loprest* Peter ....................................................................................................Josh Franklin* Sarah ........................................................................................Jeannette