Interview with Aston “Family Man” Barrett Jas Obrecht

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dub Issue 15 August2017

AIRWAVES DUB GREEN FUTURES FESTIVAL RADIO + TuneIn Radio Thurs - 9-late - Cornerstone feat.Baps www.greenfuturesfestivals.org.uk/www.kingstongreenradi o.org.uk DESTINY RADIO 105.1FM www.destinyradio.uk FIRST WEDNESDAY of each month – 8-10pm – RIDDIM SHOW feat. Leo B. Strictly roots. Sat – 10-1am – Cornerstone feat.Baps Sun – 4-6pm – Sir Sambo Sound feat. King Lloyd, DJ Elvis and Jeni Dami Sun – 10-1am – DestaNation feat. Ras Hugo and Jah Sticks. Strictly roots. Wed – 10-midnight – Sir Sambo Sound NATURAL VIBEZ RADIO.COM Daddy Mark sessions Mon – 10-midnight Sun – 9-midday. Strictly roots. LOVERS ROCK RADIO.COM Mon - 10-midnight – Angela Grant aka Empress Vibez. Roots Reggae as well as lo Editorial Dub Dear Reader First comments, especially of gratitude, must go to Danny B of Soundworks and Nick Lokko of DAT Sound. First salute must go to them. When you read inside, you'll see why. May their days overflow with blessings. This will be the first issue available only online. But for those that want hard copies, contact Parchment Printers: £1 a copy! We've done well to have issued fourteen in hard copy, when you think that Fire! (of the Harlem Renaissance), Legitime Defense and Pan African were one issue publications - and Revue du Monde Noir was issued six times. We're lucky to have what they didn't have – the online link. So I salute again the support we have from Sista Mariana at Rastaites and Marco Fregnan of Reggaediscography. Another salute also to Ali Zion, for taking The Dub to Aylesbury (five venues) - and here, there and everywhere she goes. -

What the Lens Sees Exhibit Captures Lansing in Photos, P

FREE a newspaper for the rest of us www.lansingcitypulse.com September 9-15, 2015 What the lens sees Exhibit captures Lansing in photos, p. 9 A green surprise Tea partiers push environmental incentives, p. 5 Nashville to Old Town Singer/songwriter Rachael Davis returns to Lansing, p. 12 2 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • September 9, 2015 Change a life VOLUNTEER to tutor adults in reading, English as a second language or GED preparation. — no experience necessary — Basic Training Series September 22 and 23 - 6-9 p.m. Michigan State University Confucius Institute Fuller Travel Service Inc. Wayne State University Confucius Institute Healthy & Fit Magazine call the Mrs. B’s Daycare (Tameka & Chris Billingslea) MEAT Southern BBQ & Carnivore Cuisine Miller, Caneld, Paddock & Stone, PLC Meijer – East Lansing Capital Area Literacy Coali on Cozy Koi Bed & Breakfast Kroger – East Lansing College Hunks Hauling Junk Subway of Downtown Lansing (517) 485-4949 www.thereadingpeople.org Lansing State Journal Gra Chevrolet Lansing Made LEPFA – Lansing Entertainment & Public WKAR Facilities Authority Greater Lansing Sports Authority Very Special Thanks to: Laurel Winkel of LEPFA for her dedication to dragon boating American Dragon Boat Association PRESENTS ALL of our hard working volunteers! CELEBRATING TOMATOES! 2015 Dragon Boat Teams: FEATURING THE BEST TOMATO KNIFE EVER Fire Phoenix Division Green Dragon Division Black Turtle Division MADE IN FRANCE BY LAGUIOLE Swaggin' Dragons BWL Aqua Avengers Dirty Oars Aft Kickers Flying Broncos Won Fun Bureau STAINLESS STEEL WITH ACRYLIC HANDLES IN 16 COLORS. TechSmith PaddleOars Miller Caneld Draggin' Bottom Confucius Warriors Making Waves Everett Rowing Vikings SURVIVOR TEAMS: Survivor Squirrels and WCGL SurvivOARS 211 M.A.C. -

Lyrics and the Law : the Constitution of Law in Music

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2006 Lyrics and the law : the constitution of law in music. Aaron R. S., Lorenz University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Lorenz, Aaron R. S.,, "Lyrics and the law : the constitution of law in music." (2006). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2399. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2399 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LYRICS AND THE LAW: THE CONSTITUTION OF LAW IN MUSIC A Dissertation Presented by AARON R.S. LORENZ Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2006 Department of Political Science © Copyright by Aaron R.S. Lorenz 2006 All Rights Reserved LYRICS AND THE LAW: THE CONSTITUTION OF LAW IN MUSIC A Dissertation Presented by AARON R.S. LORENZ Approved as to style and content by: Sheldon Goldman, Member DEDICATION To Martin and Malcolm, Bob and Peter. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project has been a culmination of many years of guidance and assistance by friends, family, and colleagues. I owe great thanks to many academics in both the Political Science and Legal Studies fields. Graduate students in Political Science have helped me develop a deeper understanding of public law and made valuable comments on various parts of this work. -

Sly & Robbie – Primary Wave Music

SLY & ROBBIE facebook.com/slyandrobbieofficial Imageyoutube.com/channel/UC81I2_8IDUqgCfvizIVLsUA not found or type unknown en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sly_and_Robbie open.spotify.com/artist/6jJG408jz8VayohX86nuTt Sly Dunbar (Lowell Charles Dunbar, 10 May 1952, Kingston, Jamaica, West Indies; drums) and Robbie Shakespeare (b. 27 September 1953, Kingston, Jamaica, West Indies; bass) have probably played on more reggae records than the rest of Jamaica’s many session musicians put together. The pair began working together as a team in 1975 and they quickly became Jamaica’s leading, and most distinctive, rhythm section. They have played on numerous releases, including recordings by U- Roy, Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer, Culture and Black Uhuru, while Dunbar also made several solo albums, all of which featured Shakespeare. They have constantly sought to push back the boundaries surrounding the music with their consistently inventive work. Dunbar, nicknamed ‘Sly’ in honour of his fondness for Sly And The Family Stone, was an established figure in Skin Flesh And Bones when he met Shakespeare. Dunbar drummed his first session for Lee Perry as one of the Upsetters; the resulting ‘Night Doctor’ was a big hit both in Jamaica and the UK. He next moved to Skin Flesh And Bones, whose variations on the reggae-meets-disco/soul sound brought them a great deal of session work and a residency at Kingston’s Tit For Tat club. Sly was still searching for more, however, and he moved on to another session group in the mid-70s, the Revolutionaries. This move changed the course of reggae music through the group’s work at Joseph ‘Joe Joe’ Hookim’s Channel One Studio and their pioneering rockers sound. -

Redalyc.BOB MARLEY: MEMÓRIAS, NARRATIVAS E PARADOXOS DE

Revista Brasileira do Caribe ISSN: 1518-6784 [email protected] Universidade Federal do Maranhão Brasil Rabelo, Danilo BOB MARLEY: MEMÓRIAS, NARRATIVAS E PARADOXOS DE UM MITO POLISSÊMICO Revista Brasileira do Caribe, vol. 18, núm. 35, julio-diciembre, 2017, pp. 135-164 Universidade Federal do Maranhão Sao Luís, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=159154124010 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto BOB MARLEY: MEMÓRIAS, NARRATIVAS E PARADOXOS DE UM MITO POLISSÊMICO1 BOB MARLEY: MEMORIES, NARRATIVES AND PARADOXES OF A POLYSEMOUS MYTH Danilo Rabelo Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brasil.2 Resumo Por meio da narrativa biográfica de Bob Marley (1945-1981), o artigo analisa como diferentes imagens e memórias sobre o cantor foram sendo elaboradas durante sua vida e após a sua morte, tentando estabelecer os significados, apropriações, estratégias políticas e interesses em jogo. Como mais famoso porta-voz do reggae e do rastafarismo, as memórias sobre Marley revelam as contradições e paradoxos da sociedade envolvente jamaicana quanto ao uso das imagens elaboradas sobre o cantor. Palavras-Chave: Bob Marley; Reggae; Rastafari; Jamaica; Memória. Abstract Through the biographical narrative of Bob Marley (1945-1981), the article analyzes how different images and memories about the singer were elaborated during his life and after his death, trying to establish the meanings, appropriations, political strategies and interests at stake. As the most celebrated spokesman for reggae and Rastafarianism, Marley’s memoirs reveal the contradictions and paradoxes of Jamaican society surrounding the use of elaborated images of the singer. -

To See the 2018 Pier Concert Preview Guide

2 TWILIGHTSANTAMONICA.ORG REASON 1 #1 in Transfers for 27 Years APPLY AT SMC.EDU SANTA MONICA COMMUNITY COLLEGE DISTRICT BOARD OF TRUSTEES Barry A. Snell, Chair; Dr. Margaret Quiñones-Perez, Vice Chair; Dr. Susan Aminoff; Dr. Nancy Greenstein; Dr. Louise Jaffe; Rob Rader; Dr. Andrew Walzer; Alexandria Boyd, Student Trustee; Dr. Kathryn E. Jeffery, Superintendent/President Santa Monica College | 1900 Pico Boulevard | Santa Monica, CA 90405 | smc.edu TWILIGHTSANTAMONICA.ORG 3 2018 TWILIGHT ON THE PIER SCHEDULE SEPT 05 LATIN WAVE ORQUESTA AKOKÁN Jarina De Marco Quitapenas Sister Mantos SEPT 12 AUSTRALIA ROCKS THE PIER BETTY WHO Touch Sensitive CXLOE TWILIGHT ON THE PIER Death Bells SEPT 19 WELCOMES THE WORLD ISLAND VIBES f you close your eyes, inhale the ocean Instagram feeds, and serves as a backdrop Because the event is limited to the land- JUDY MOWATT Ibreeze and listen, you’ll hear music in in Hollywood blockbusters. mark, police can better control crowds and Bokanté every moment on the Santa Monica Pier. By the end of last year, the concerts had for the first time check bags. Fans will still be There’s the percussion of rubber tires reached a turning point. City leaders grappled allowed to bring their own picnics and Twilight Steel Drums rolling over knotted wood slats, the plinking with an event that had become too popular for water bottles for the event. DJ Danny Holloway of plastic balls bouncing in the arcade and its own good. Police worried they couldn’t The themes include Latin Wave, Australia the song of seagulls signaling supper. -

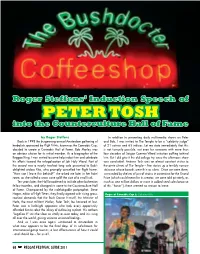

Peter Tosh Into the Counterculture Hall of Fame

Roger Steffens’ Induction Speech of PETER TOSH into the Counterculture Hall of Fame by Roger Steffens In addition to presenting daily multi-media shows on Peter Back in 1998 the burgeoning annual Amsterdam gathering of and Bob, I was invited to The Temple to be a “celebrity judge” herbalists sponsored by High Times, known as the Cannabis Cup, of 21 sativas and 63 indicas. Let me state immediately that this decided to create a Cannabis Hall of Fame. Bob Marley was is not humanly possible, not even for someone with more than an obvious choice for its initial member. As a biographer of the four decades of Saigon-Commie-Weed initiation puffing behind Reggae King, I was invited to come help induct him and celebrate him. But I did give it the old college try, once the afternoon show his efforts toward the re-legalization of Jah Holy Weed. Part of was concluded. Andrew Tosh was an almost constant visitor to the award was a nearly two-foot long cola presented to Bob’s the aerie climes of The Temple – five stories up a terribly narrow delighted widow Rita, who promptly cancelled her flight home. staircase whose boards were thin as rulers. Once we were there, “How can I leave this behind?” she asked me later in her hotel surrounded by shelves of jars of strains in contention for the Grand room, as she rolled a snow cone spliff the size of a small tusk. Prize (which could mean for its creator, we were told privately, as Ten years later, the Hall broadened to include other bohemian much as one million dollars or more in added seed sales because fellow travelers, and changed its name to the Counterculture Hall of this “honor”), there seemed no reason to leave. -

Biography Kwame “Akompreko” Bediako

Biography Kwame “Akompreko” Bediako Musician and poet Kwame “Akompreko” Bediako credits his musical upbringing to his elders and his general environment of his home back in Ghana (West Africa), where his roots first blossomed. “Back at home there was always drumming, singing, and dancing. Traditionally almost everyone can sing and dance so embracing the professional idea was a slower process, but most things happen empirically anyway,” says Kwame. In addition to his heritage/culture and elders, Kwame also attributes his musical talents and stage presence to Bob Marley and Tom Waits, two of his biggest musical influences. Kwame and his band, Wan Afrika, exudes positive energy in their live performances, while simultaneously addressing the joys and sorrows of humanity within the music. From this Kwame has earned another moniker as Africa’s High Priest of Roots Reggae. “To educate and entertain is the goal. We are proponents of the knowledge of the self, and we advocate a One Africa. We are taking learning beyond the traditional classroom. The Akans say ‘Yeenom nsa na yee fa adwen.’” The band has performed throughout the United States, Canada, the Caribbean, his homeland Ghana, and with the 2012 United Nations sponsored "International Year of People of Afrikan Descent" (IYPAD) tour. Kwame has shared the bill with notables like the Wailers, Third World, Mutabaruka, Pato Banton, Sonny Ade, Wailing Souls, Sonny Okusun and many others. Kwame has been the recipient of many industry awards and honorable mentions including: Martin International's Chicago Reggae Music Awards "Best Artist" and "Most Culture-Oriented Band." “The Lord gave the word and great is the company that publishes it, and the word here is One Africa, meaning a united Africa. -

El Rototom Celebra El Concierto Inédito De La Banda Original De Bob

jueves 17 de agosto de 2017 | Periódico Todo Benicàssim El Rototom celebra el concierto inédito de la banda original de Bob Marley, The Wailers La sexta jornada del festival vivirá un hecho histórico: el reencuentro de The Wailers, con un concierto que está previsto a las 0.30 horas, en el Main Stage Eva Bellido // Benicàssim El Rototom ha rebasado ya el ecuador del festival registrando más de 100.000 asistentes de 98 nacionalidades en esta 24 edición Celebrating Africa. El macroevento reggae enfila desde este jueves en Benicàssim sus últimas, pero intensas, 72 horas de actividad. La sexta jornada del festival vivirá un hecho histórico: el reencuentro de The Wailers, la banda original del Rey del Reggae, Bob Marley, con un concierto que está previsto a las 0.30 horas, en el Main Stage. Cuatro décadas después de que Bob Marley cantaraAfrica Unite y recibiera la Medalla de la Paz de la ONU en 1978 de parte del Youth Ambassador senegalés, su grupo originario está de vuelta para la edición más africana de la historia del Sunsplash. Miembros originales de The Wailers como AstonFamilyman Barrett (bajo), Tyrone Downie (teclados), Junior Marvin y Donald Kinsey (guitarras) se reúnen sobre el Main Stage para interpretar aquella música que cambió el mundo inspirando la independencia africana. El cantante principal es Josh David Barrett, en este especial tour de la banda liderada por Bob Marley, que falleció en 1981 a consecuencia de un cáncer. A ellos se unirá Aston Barrett Junior en la batería, hijo de Familyman y, representando a la nueva generación; Shema McGregor (coros), hija de la componente de The I Threes, Judy Mowatt y de Freddie McGregor. -

The Best Bob Marley and the Wailers

National Library of Jamaica "ONE LOVE", a St•ng that recently shot lnck to the top of the Brit1sh pop charts. "I SHO T THE '•HERIFF", agam featur .ng the origmal Waders from the Album Bur nm'. The song provided fnc Clapton w1th an Amencan hit. "WAIT! G IN VAIN", from the LP Exodus. "REDEM PTI ON SONG", from Upnsing. A \ ery nch song of ex hortauon done with the smooth sounds of the acousnc gu1tar. "S ATI SFY MY SOUL". "EXO DUS", from the album of the same name. One of the f�w Reggae songs that scored big on both s1des of the AtlantiC. "J AMMING", an other hit single from the album Exodus. Several exciting pic tures recording the Mar ley phenomenon help to decorate the album's outer jacket, while the mner section has pic· tures of Marley mem orabilia, from concert posters and album Jack et� to newspaper clip pmgs and record labels. Marley's legendary sales Wming in the June 1ssue of Music Week resenrative of rhe bc�r next eight records in the t-.1ay, 1981, Magazine, commenta � Marie� or Wa ilers album chart.'' bert N esta Marie Jor Alan Jones dest:ribed �ounds, and as soon as T. Riley k · ,\farle) Legend as rep J.IVI., R• eggae mg o \ ("' '• one starts to enjoy the thl' world, died of resentatiYe of a maJor \Ong�. they seem to end. bounce-back in the Bm cancer. This year, Is- I think a double LP tsh recording mdust!]. ha e land Records v would have served the Sale,, he wrote, were paid tribute to a rn.1n 1nrended purposes more �taggering. -

Rototom Reggae University 2008

ROTOTOM REGGAE UNIVERSITY 2008 ! ! July 4 FROM RUDE BOYS TO SHOTTAS Violence and Alienation in Jamaican Cultural Expression Lecture, film-shoots and selected music by !Marlene Calvin JA/DE July 5 RASTAFARI - Unity and Diversity of a Global Philosophy with prof Werner Zips from the University of Wien, Bob Andy, Sydney Salmon, Jamaican artist who lives in Shashamane, and Leila Worku, director of the Ethiopia’s Bright Millennium Campaign. Film shoots from “Rastafari: Death to Black and White !Downpressors” by Werner Zip July 6 REGGAE IN ITALY with Bunna of Africa Unite, Treble, former SudSoundSystem and nowadays producer, Jaka, entertainer, singer and radio dee-jay, Paolo Baldini, members of Train To Roots, Suoni Mudù, Villa Ada Posse, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Anzikitanza, the singers of Big Island Records, Filippo Giunta (Rototom), Steve Giant (Rasta Snob), Vito War (Reggae Radio Station on Popolare Network), Macromarco (Gramigna Sound), Lampadread (OneLoveHi Powa). July 10 ROOTS MUSIC IN THE DANCEHALL !with Michael Rose and Alborosie ! ! July 10 DEEP ROOTS MUSIC A meeting with Howard Johnson, film-maker !and director of “DeepRootsMusic” ! July 7 FEMALE REGGAE A Change of Position from Margin to Centre? with Jamaican artist Ce’Cile, Yaz Alexander, from UK, The Reggae Girls from Italy, and The Serengeti from Sweden. !Dub-poetry performance by Jazzmine TuTum ! July 7 NEW TRENDS IN THE DANCEHALL with Wayne Marshall, Bugle, Teflon, !and Daseca producers ! July 8 EVERLASTING FOUNDATION The Crucial Role of Musicians In Jamaica with Dean Frazer, -

Samson and Moses As Moral Exemplars in Rastafari

WARRIORS AND PROPHETS OF LIVITY: SAMSON AND MOSES AS MORAL EXEMPLARS IN RASTAFARI __________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board __________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY __________________________________________________________________ by Ariella Y. Werden-Greenfield July, 2016 __________________________________________________________________ Examining Committee Members: Terry Rey, Advisory Chair, Temple University, Department of Religion Rebecca Alpert, Temple University, Department of Religion Jeremy Schipper, Temple University, Department of Religion Adam Joseph Shellhorse, Temple University, Department of Spanish and Portuguese © Copyright 2016 by Ariella Y. Werden-Greenfield All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT Since the early 1970’s, Rastafari has enjoyed public notoriety disproportionate to the movement’s size and humble origins in the slums of Kingston, Jamaica roughly forty years earlier. Yet, though numerous academics study Rastafari, a certain lacuna exists in contemporary scholarship in regards to the movement’s scriptural basis. By interrogating Rastafari’s recovery of the Hebrew Bible from colonial powers and Rastas’ adoption of an Israelite identity, this dissertation illuminates the biblical foundation of Rastafari ethics and symbolic registry. An analysis of the body of scholarship on Rastafari, as well as of the reggae canon, reveals