20170104-Approved Thesis-Butler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Armed Forces (Offences and Jurisdiction) (Jersey) Law 201

STATES OF JERSEY r DRAFT ARMED FORCES (OFFENCES AND JURISDICTION) (JERSEY) LAW 201- Lodged au Greffe on 6th June 2017 by the Minister for Home Affairs STATES GREFFE 2017 P.51 DRAFT ARMED FORCES (OFFENCES AND JURISDICTION) (JERSEY) LAW 201- European Convention on Human Rights In accordance with the provisions of Article 16 of the Human Rights (Jersey) Law 2000, the Minister for Home Affairs has made the following statement – In the view of the Minister for Home Affairs, the provisions of the Draft Armed Forces (Offences and Jurisdiction) (Jersey) Law 201- are compatible with the Convention Rights. Signed: Deputy K.L. Moore of St. Peter Minister for Home Affairs Dated: 2nd June 2017 Page - 3 ◊ P.51/2017 REPORT The proposed Armed Forces (Offences and Jurisdiction) (Jersey) Law 201- (“the proposed Law”) makes provision for the treatment of British armed forces and those visiting from other countries when they are in Jersey, particularly in relation to discipline and justice. The proposed Law also establishes appropriate powers for the Jersey police and courts in relation to deserters and others, creates civilian offences in relation to the armed forces, protects the pay and equipment of the armed forces from action in Jersey courts, and enables the States Assembly by Regulations to amend legislation to provide for the use of vehicles and roads by the armed forces. Background The United Kingdom Visiting Forces Act 1952 was introduced in order to make provision with respect to naval, military and air forces of other countries visiting the United Kingdom, and to provide for the apprehension and disposal of deserters or absentees without leave in the United Kingdom from the forces of such countries. -

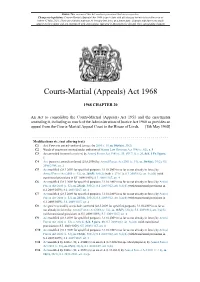

Courts-Martial (Appeals) Act 1968 Is up to Date with All Changes Known to Be in Force on Or Before 05 May 2021

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: Courts-Martial (Appeals) Act 1968 is up to date with all changes known to be in force on or before 05 May 2021. There are changes that may be brought into force at a future date. Changes that have been made appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) View outstanding changes Courts-Martial (Appeals) Act 1968 1968 CHAPTER 20 An Act to consolidate the Courts-Martial (Appeals) Act 1951 and the enactments amending it, including so much of the Administration of Justice Act 1960 as provides an appeal from the Courts-Martial Appeal Court to the House of Lords. [8th May 1968] Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 Act: Power to amend conferred (prosp.) by 2001 c. 19, ss. 30(4)(e), 39(2) C2 Words of enactment omitted under authority of Statute Law Revision Act 1948 (c. 62), s. 3 C3 Act amended (women's services) by Armed Forces Act 1981 (c. 55, SIF 7:1), s. 20, Sch. 3 Pt. I para. 1 C4 Act: power to amend conferred (25.8.2006) by Armed Forces Act 2001 (c. 19), ss. 30(4)(e), 39(2); S.I. 2006/2309, art. 2 C5 Act modified (28.3.2009 for specified purposes, 31.10.2009 in so far as not already in force) by Armed Forces Act 2006 (c. 52), ss. 268(5), 383(2) (with s. 271(1)); S.I. 2009/812, art. 3(a)(b) (with transitional provisions in S.I. -

1. Craig Prescott

Title Page ENHANCING THE METHODOLOGY OF FORMAL CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE IN THE UK A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2014 CRAIG PRESCOTT SCHOOL OF LAW Contents Title Page 1 Contents 2 Table of Abbreviations 5 Abstract 6 Declaration 7 Copyright Statement 8 Acknowledgements 9 Introduction 10 1. ‘Constitutional Unsettlement’ 11 2. Focus on Procedures 18 3. Outline of the Thesis 24 Chapter 1 - Definitions 26 1. ‘Constitutional’ 26 2. ‘Change’ 34 3. ‘Constitutional Change’ 36 4. Summary 43 Chapter 2 - The Limits of Formal Constitutional Change: Pulling Iraq Up By Its Bootstraps 44 1. What Are Constitutional Conventions? 45 Page "2 2. Commons Approval of Military Action 48 3. Conclusion 59 Chapter 3 - The Whitehall Machinery 61 1. Introduction 61 2. Before 1997 and New Labour 66 3. Department for Constitutional Affairs 73 4. The Coalition and the Cabinet Office 77 5. Where Next? 82 6. Conclusion 92 Chapter 4 - The Politics of Constitutional Change 93 1. Cross-Party Co-operation 93 2. Coalition Negotiations 95 3. Presentation of Policy by the Coalition 104 4. Lack of Consistent Process 109 Chapter 5 - Parliament 114 1. Legislative and Regulatory Reform Act 2006 119 2. Constitutional Reform Act 2005 133 3. Combining Expertise With Scrutiny 143 4. Conclusion 156 Chapter 6 - The Use of Referendums in the Page "3 UK 161 1. The Benefits of Referendums 163 2. Referendums and Constitutional Change 167 3. Referendums In Practice 174 4. Mandatory Referendums? 197 5. Conclusion 205 Chapter 7 - The Referendum Process 208 1. -

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

SUBMISSION TO THE UNITED NATIONS’ COMMITTEE ON ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RIGHTS Parallel Report on the Sixth Periodic Report of the United Kingdom under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights September 2015 Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission Temple Court, 39 North Street Belfast BT1 1NA Tel: +44 (0) 28 9024 3987 Fax: +44 (0) 28 9024 7844 Textphone: +44 (0) 28 9024 9066 SMS Text: +44 (0) 7786 202075 Email: [email protected] Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 11 Ratification of Optional Protocol ........................................................................................................... 11 Involvement of NI Executive in treaty reporting .................................................................................... 12 Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission ........................................................................................ 12 Constitutional and legal framework .......................................................................................................... 13 Incorporation of economic, social and cultural rights ............................................................................ 13 Human Rights Act and proposed repeal ....................................................................................... 13 Relationship of Human Rights Act to NI peace agreements ......................................................... -

Armed Forces Bill: Lords Amendments

Armed Forces Bill: Lords Amendments Standard Note: SN06083 Last updated: 3 November 2011 Author: Claire Taylor Section International Affairs and Defence Section The Armed Forces Bill passed to the House of Lords in June 2011 (HL Bill 76 2010-12). Second reading took place on 6 July, while the Committee stage took place over 6 and 8 September 2011. Report Stage in the Lords took place on 4 October 2011. No amendments to the Bill were passed during those initial Lords stages. However, six amendments to the Bill were agreed at Third Reading which took place on 10 October, including several tabled or supported by the Government. Those amendments largely related to the Armed Forces Covenant, although one also examined the issue of Commonwealth medals. The Bill was returned to the Commons for consideration (Bill 232) on 19 October. Five of those amendments were agreed to, although the amendment relating to medals was not agreed following a division of the House. The Bill subsequently returned to the Lords and was considered on 26 October. The Lords agreed not to push for the amendment and the Bill was passed. The Armed Forces Act 2011 received Royal Assent on 3 November 2011. This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. It should not be relied upon as being up to date; the law or policies may have changed since it was last updated; and it should not be relied upon as legal or professional advice or as a substitute for it. -

Armed Forces Act 2011

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Armed Forces Act 2011. (See end of Document for details) Armed Forces Act 2011 2011 CHAPTER 18 An Act to continue the Armed Forces Act 2006; to amend that Act and other enactments relating to the armed forces and the Ministry of Defence Police; to amend the Visiting Forces Act 1952; to enable judge advocates to sit in civilian courts; to repeal the Naval Medical Compassionate Fund Act 1915; to make provision about the call out of reserve forces; and for connected purposes. [3rd November 2011] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— Duration of Armed Forces Act 2006 F11 Duration of Armed Forces Act 2006 . Textual Amendments F1 S. 1 omitted (12.5.2016) by virtue of Armed Forces Act 2016 (c. 21), ss. 1(2), 19(2)(a) Armed forces covenant report 2 Armed forces covenant report After section 343 of AFA 2006 insert— 2 Armed Forces Act 2011 (c. 18) Part 16A – Armed forces covenant report Document Generated: 2021-03-26 Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Armed Forces Act 2011. (See end of Document for details) “PART 16A ARMED FORCES COVENANT REPORT 343A Armed forces covenant report (1) The Secretary of State must in each calendar year— (a) prepare an armed forces covenant report; and (b) lay a copy of the report before Parliament. -

Wales and the Jurisdiction Question

This is a repository copy of How to do things with jurisdictions: Wales and the jurisdiction question. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/127304/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Percival, R. (2017) How to do things with jurisdictions: Wales and the jurisdiction question. Public Law, 2017 (2). pp. 249-269. ISSN 0033-3565 This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Public Law following peer review. The definitive published version Percival, R., How to do things with jurisdictions: Wales and the jurisdiction question, Public Law, 2017 (2), 249-269 is available online on Westlaw UK or from Thomson Reuters DocDel service . Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ How to Do Things with Jurisdictions: Wales and the Jurisdiction Question Richard Percival* Senior Research Fellow, Cardiff University Introduction There is a recurring debate amongst lawyers and policy makers about the desirability of Wales becoming a separate, fourth, UK jurisdiction. -

Memorandum to the Joint Committee on Human Rights

MEMORANDUM TO THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RIGHTS THE ARMED FORCES BILL 2015 1. The Armed Forces Bill makes provision with respect to a range of matters relating to defence and the armed forces. It also renews, subject to amendments made by the Bill, the Armed Forces Act 2006, which would otherwise expire at the end of 2016. Renewal of the Armed Forces Act 2006 (clause 1) 2. Since the Bill of Rights 1688, the legislation making the provision necessary for the army to exist as a disciplined force (and, more recently, the legislation for the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force) has been subject to regular renewal by Act of Parliament. Since the 1950s, renewal has been by five-yearly Armed Forces Act, each Act renewing the legislation for one year and permitting further annual renewal thereafter by Order in Council. Accordingly, clause 1 of the Bill provides for the continuation, for a further period up to the end of 2021, of the Armed Forces Act 2006 (“the 2006 Act”), which would otherwise expire at the end of 2016. A further Act will then be required. 3. The 2006 Act governs all the armed forces of the United Kingdom. The Act introduced a single system of service law that applies to all service personnel wherever in the world they are operating. The Act provides nearly all the provisions for the existence of a system for the armed forces of command, discipline and justice. It covers matters such as offences, the powers of the service police, and the jurisdiction and powers of commanding officers and of the service courts, in particular the Court Martial. -

The Queen's Regulations for the Army 1975

QR(Army) Amdt 37 – May 19 AC 13206 THE QUEEN'S REGULATIONS FOR THE ARMY 1975 UK Ministry of Defence © Crown Copyright 2019. This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications AEL 112 i AC 13206 QR(Army) Amdt 37 – May 19 Intentionally blank AEL 112 ii AC 13206 QR(Army) Amdt 37 – May 19 HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN has been graciously pleased to approve the following revised ‘The Queen's Regulations for the Army' and to command that they be strictly observed on all occasions. They are to be interpreted reasonably and intelligently, with due regard to the interests of the Service, bearing in mind that no attempt has been made to provide for necessary and self-evident exceptions. Commanders at all levels are to ensure that any local orders or instructions that may be issued are guided and directed by the spirit and intention of these Regulations. By Command of the Defence Council Ministry of Defence January 2019 AEL 112 iii AC 13206 QR(Army) Amdt 37 – May 19 Intentionally blank AEL 112 iv AC 13206 QR(Army) Amdt 37 – May 19 THE QUEEN'S REGULATIONS FOR THE ARMY 1975 (Amendment No 36) PREFACE 1. -

Armed Forces Bill Explanatory Notes

ARMED FORCES BILL EXPLANATORY NOTES What these notes do These Explanatory Notes relate to the Armed Forces Bill as introduced in the House of Commons on 16 September 2015 (Bill 70). • These Explanatory Notes have been prepared by the Ministry of Defence in order to assist the reader of the Bill and to help inform debate on it. They do not form part of the Bill and have not been endorsed by Parliament. • These Explanatory Notes explain what each part of the Bill will mean in practice; provide background information on the development of policy; and provide additional information on how the Bill will affect existing legislation in this area. • These Explanatory Notes might best be read alongside the Bill. They are not, and are not intended to be, a comprehensive description of the Bill. So where a provision of the Bill does not seem to require any explanation or comment, the Notes simply say in relation to it that the provision is self‐explanatory. Bill 70–EN 56/1 Table of Contents Subject Page of these Notes Overview of the Bill 2 Policy background 2 Legal background 2 Territorial extent and application 3 Territorial application of the Bill in the UK 3 Territorial application of the Bill outside the UK 4 Commentary on provisions of Bill 5 Clause 1: Duration of AFA 2006 5 Clause 2: Commanding officer’s power to require preliminary alcohol and drugs tests 5 Clause 3: Duty of service policeman following investigation 6 Clause 4: Power of commanding officer to charge etc 7 Clause 5: Power of Director of Service Prosecutions to charge etc 7 -

Armed Forces Covenant Annual Report 2014

THE ARMED FORCES COVENANT ANNUAL REPORT 2014 Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 2 of the Armed Forces Act 2011 THE ARMED FORCES COVENANT ANNUAL REPORT 2014 Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 2 of the Armed Forces Act 2011 The Armed Forces Covenant An Enduring Covenant Between The People of the United Kingdom Her Majesty’s Government – and – All those who serve or have served in the Armed Forces of the Crown And their Families The first duty of Government is the defence of the realm. Our Armed Forces fulfil that responsibility on behalf of the Government, sacrificing some civilian freedoms, facing danger and, sometimes, suffering serious injury or death as a result of their duty. Families also play a vital role in supporting the operational effectiveness of our Armed Forces. In return, the whole nation has a moral obligation to the members of the Naval Service, the Army and the Royal Air Force, together with their families. They deserve our respect and support, and fair treatment. Those who serve in the Armed Forces, whether Regular or Reserve, those who have served in the past, and their families, should face no disadvantage compared to other citizens in the provision of public and commercial services. Special consideration is appropriate in some cases, especially for those who have given most such as the injured and the bereaved. This obligation involves the whole of society: it includes voluntary and charitable bodies, private organisations, and the actions of individuals in supporting the Armed Forces. Recognising those who have performed military duty unites the country and demonstrates the value of their contribution. -

Army Headquarters Secretariat IDL 24 Marlborough Lines Monxton Road ANDOVER SP11 8HJ E-Mail: [email protected] Website

Army Headquarters Secretariat IDL 24 Marlborough Lines Monxton Road ANDOVER SP11 8HJ E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.army.mod.uk Ms L Mowday Our Reference: Army/Sec/03/12 what dot heyknow.co m Via Date: 28 September 2012 Dear Ms Mowday FOI REQUESTS – VARIOUS On 9 and 10 September 2012 you raised 20 separate requests for information under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. You then raised an additional 10 questions on 26 September. Under the Appropriate Limit and Fees Regulations, public authorities are able to aggregate two or more requests if they are received within 60 working days and "relate, to any extent, to the same or similar information". In this case, the requests on the enclosed table (a total of 22) relate to the Armed Forces Act, and related conduct of the Service Justice System and military discipline, and they were all received within a period of sixty working days. These requests have therefore been aggregated. In line with the regulations, the estimated cost of complying with any of the requests is taken to be the total costs of complying with all of them. I can confirm that we may hold some information on the subjects you have requested. However, it has been assessed that the costs for which we are permitted to charge in providing this information will exceed the appropriate limit. This appropriate limit is specified in regulations and for central government is set at £600. This represents the estimated cost of one person spending three and a half working days in determining whether the Department holds the information, and locating, retrieving and extracting the information.