Losing the Vote

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unemployment Benefits and Reservation Wages: Key Elasticities from a Stripped-Down Job Search Approach

Estudos e Documentos de Trabalho Working Papers 3 | 2008 UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFITS AND RESERVATION WAGES: KEY ELASTICITIES FROM A STRIPPED-DOWN JOB SEARCH APPROACH John T. Addison Mário Centeno Pedro Portugal February 2008 The analyses, opinions and findings of these papers represent the views of the authors, they are not necessarily those of the Banco de Portugal. Please address correspondence to Pedro Portugal Economics and Research Department Banco de Portugal, Av. Almirante Reis no. 71, 1150-012 Lisboa, Portugal; Tel.: 351 213 138 410, Email: [email protected] BANCO DE PORTUGAL Economics and Research Department Av. Almirante Reis, 71-6th floor 1150-012 Lisboa www.bportugal.pt Printed and distributed by Administrative Services Department Av. Almirante Reis, 71-2nd floor 1150-012 Lisboa Number of copies printed 170 issues Legal Deposit no. 3664/83 ISSN 0870-0117 ISBN Unemployment Benefits and Reservation Wages: Key Elasticities from a Stripped-Down Job Search Approach By John T. Addison†,M´ario Centeno‡ and Pedro Portugal§ †Queen’s University Belfast and University of South Carolina ‡Banco de Portugal and Universidade T´ecnica de Lisboa §Banco de Portugal and Universidade NOVA de Lisboa This Version: February 2008 Abstract This paper exploits survey information on reservation wages and data on actual wages from the European Community Household Panel to deduce in the manner of Lancaster and Chesher (1983) additional parameters of a stylized structural search model; specifically, reservation wage and transition/duration elasticities. The informational requirements of this approach are minimal, thereby facilitating comparisons between countries. Further, its policy content is immediate insofar as the impact of unemployment benefit rules and measures increasing the arrival rate of job offers are concerned. -

Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: the President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected]

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 2-2012 Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The President and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment Beth Behn University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Behn, Beth, "Woodrow Wilson's Conversion Experience: The rP esident and the Federal Woman Suffrage Amendment" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 511. https://doi.org/10.7275/e43w-h021 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/511 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2012 Department of History © Copyright by Beth A. Behn 2012 All Rights Reserved WOODROW WILSON’S CONVERSION EXPERIENCE: THE PRESIDENT AND THE FEDERAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE AMENDMENT A Dissertation Presented by BETH A. BEHN Approved as to style and content by: _________________________________ Joyce Avrech Berkman, Chair _________________________________ Gerald Friedman, Member _________________________________ David Glassberg, Member _________________________________ Gerald McFarland, Member ________________________________________ Joye Bowman, Department Head Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would never have completed this dissertation without the generous support of a number of people. It is a privilege to finally be able to express my gratitude to many of them. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Map .................................................................................................................................. i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions of Apartheid and Persecution ................................................................................. -

Parades, Pickets, and Prison: Alice Paul and the Virtues of Unruly Constitutional Citizenship

PARADES, PICKETS, AND PRISON: ALICE PAUL AND THE VIRTUES OF UNRULY CONSTITUTIONAL CITIZENSHIP Lynda G. Dodd* INTRODUCTION: MODELS OF CONSTITUTIONAL CITIZENSHIP For all the recent interest in “popular constitutionalism,” constitutional theorists have devoted surprisingly little attention to the habits and virtues of citizenship that constitutional democracies must cultivate, if they are to flourish.1 In my previous work, I have urged scholars of constitutional politics to look beyond judicial review and other more traditional checks and balances intended to prevent governmental misconduct, in order to examine the role of “citizen plaintiffs”2 – individuals who, typically at great personal cost in a legal culture where the odds are stacked against them, attempt to enforce their rights in * 1 For some exceptions, see Walter F. Murphy, CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY: CREATING AND MAINTAINING A JUST POLITICAL ORDER (2007); JAMES E. FLEMING, SECURING CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY: THE CASE FOR AUTONOMY (2006); Wayne D. Moore, Constitutional Citizenship in CONSTITUTIONAL POLITICS: ESSAYS ON CONSTITUTIONAL MAKING, MAINTENANCE, AND CHANGE (Sotirios A. Barber and Robert P. George, eds. 2001); Paul Brest, Constitutional Citizenship, 34 CLEV. ST. L. REV. 175 (1986). 2 Under this model of citizenship, the citizen plaintiff is participating in the process of constitutional checks and balances. That participation can be described in terms of “enforcing” constitutional norms or “protesting” the government’s departure from them. The phrase “private attorneys general” is the traditional term used to describe citizen plaintiffs. See, e.g., David Luban, Taking Out the Adversary: The Assault on Progressive Public Interest Lawyers, 91 CAL. L. REV. 209 (2003); Pamela Karlan, Disarming the Private Attorney General, 2003 U. -

Helping Women to Recover: Creating Gender-Specific Treatment for Substance-Abusing Women and Girls in Community Correctional Settings

Helping Women to Recover: Creating Gender-Specific Treatment for Substance-Abusing Women and Girls in Community Correctional Settings Stephanie S. Covington, Ph.D., LCSW Co-Director, Center for Gender and Justice La Jolla, California Presented at: International Community Corrections Association Arlington, Virginia 1998 Published in: In M. McMahon, ed., Assessment to Assistance: Programs for Women in Community Corrections. Latham, Md.: American Correctional Association, 2000, 171-233. Some of the most neglected and misunderstood women and girls in North America are those in the criminal justice system. Largely because of the “War on Drugs,” the rate of incarceration for women in the United States has tripled since 1980 (Bloom , Chesney- Lind, & Owen., 1994; Collins & Collins, 1996). Between 1986 and 1991, the number of women in state prisons for drug-related offenses increased by 432 percent (Phillips & Harm, 1998). Like their juvenile counterparts, most of these women are non-violent offenders who could be treated much more effectively and economically in community- based gender-specific programs. When females are not a security risk, community-based sanctions offer benefits to society, to female offenders1 themselves, and to their children. One survey compares an $869 average annual cost for probation to $14,363 for jail and $17,794 for prison (Phillips & Harm, 1998). Community corrections disrupt females’ lives less than does incarceration and subject them to less isolation. Further, community corrections potentially disrupt the lives of children far less. Unfortunately, few drug treatment programs exist that address the needs of females, especially those with minor children. This is unfortunate because, when allied with probation, electronic monitoring, community service, and/or work release, community-based substance abuse treatment could be an effective alternative to the spiraling rates of recidivism and re-incarceration. -

Institutionalizing the Pennsylvania System: Organizational Exceptionalism, Administrative Support, and Eastern State Penitentiary, 1829–1875

Institutionalizing the Pennsylvania System: Organizational Exceptionalism, Administrative Support, and Eastern State Penitentiary, 1829–1875 By Ashley Theresa Rubin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Malcolm Feeley, Chair Professor Cybelle Fox Professor Calvin Morrill Professor Jonathan Simon Spring 2013 Copyright c 2013 Ashley Theresa Rubin All rights reserved Abstract Institutionalizing the Pennsylvania System: Organizational Exceptionalism, Administrative Support, and Eastern State Penitentiary, 1829–1875 by Ashley Theresa Rubin Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy University of California, Berkeley Professor Malcolm Feeley, Chair I examine the puzzling case of Eastern State Penitentiary and its long-term retention of a unique mode of confinement between 1829 and 1875. Most prisons built in the nineteenth cen- tury followed the “Auburn System” of congregate confinement in which inmates worked daily in factory-like settings and retreated at night to solitary confinement. By contrast, Eastern State Penitentiary (f. 1829, Philadelphia) followed the “Pennsylvania System” of separate confinement in which each inmate was confined to his own cell for the duration of his sentence, engaging in workshop-style labor and receiving religious ministries, education, and visits from selected person- nel. Between 1829 and the 1860s, Eastern faced strong pressures to conform to field-wide norms and adopt the Auburn System. As the progenitor of the Pennsylvania System, Eastern became the target of a debate raging over the appropriate model of “prison discipline.” Supporters of the Auburn System (penal reformers and other prisons’ administrators) propagated calumnious myths, arguing that the Pennsylvania System was cruel and inhumane, dangerous to inmates’ physical and mental health, too expensive, and simply impractical and ineffective. -

First Name Last Name Title Company Country Anouk Florencia Aaron Warner Bros

First Name Last Name Title Company Country Anouk Florencia Aaron Warner Bros. International Television United States Carlos Abascal Director, Ole Communications Ole Communications United States Kelly Abcarian SVP, Product Leadership Nielsen United States Mike Abend Director, Business Development New Form Digital United States Friday Abernethy SVP, Content Distribution Univision Communications Inc United States Jack Abernethy Twentieth Television United States Salua Abisambra Manager Salabi Colombia Rafael Aboy Account Executive Newsline Report Argentina Cori Abraham SVP of Development and International Oxygen Network United States Mo Abraham Camera Man VIP Television United States Cris Abrego Endemol Shine Group Netherlands Cris Abrego Chairman, Endemol Shine Americas and CEO, Endemol Shine North EndemolAmerica Shine North America United States Steve Abrego Endemol Shine North America United States Patrícia Abreu Dirctor Upstar Comunicações SA Portugal Manuel Abud TV Azteca SAB de CV Mexico Rafael Abudo VIP 2000 TV United States Abraham Aburman LIVE IT PRODUCTIONS Francine Acevedo NATPE United States Hulda Acevedo Programming Acquisitions Executive A+E Networks Latin America United States Kristine Acevedo All3Media International Ric Acevedo Executive Producer North Atlantic Media LLC United States Ronald Acha Univision United States David Acosta Senior Vice President City National Bank United States Jorge Acosta General Manager NTC TV Colombia Juan Acosta EVP, COO Viacom International Media Networks United States Mauricio Acosta President and CEO MAZDOC Colombia Raul Acosta CEO Global Media Federation United States Viviana Acosta-Rubio Telemundo Internacional United States Camilo Acuña Caracol Internacional Colombia Andrea Adams Director of Sales FilmTrack United States Barbara Adams Founder Broken To Reign TV United States Robin C. Adams Executive In Charge of Content and Production Endavo Media and Communications, Inc. -

Becoming a Detective: Historical Case File #5—Prisoners and Hunger

Becoming a Detective: Historical Case peacefully exercising their right to petition their File #5—Prisoners and Hunger Strikes government. Because they believed themselves to be political prisoners, the women refused to At the request of the textbook committee your cooperate with their jailors. class has been asked to investigate whether Hazel Hunkins deserves to be included in the According to an article published on the website next edition of the textbook. This case cannot American Memory, the imprisoned women were be solved without an understanding of the “sometimes beaten (most notably during the National Woman’s Party’s decision to com- November 15 “Night of Terror” at Occoquan mit civil disobedience, their demands to be Workhouse), and often brutally force-fed when treated as political prisoners, and the attention they went on hunger strikes to protest being their imprisonment brought to the cause. As a denied political prisoner status. Women of all member of the commission selected to review classes risked their health, jobs, and reputations the case, your job is to examine the following by continuing their protests. One historian documents to better understand the why these estimated that approximately 2,000 women women decided to break the law and what af- spent time on the picket lines between 1917 fect their actions had. and 1919, and that 500 women were arrested, of whom 168 were actually jailed. The NWP • Why did suffrage prisoners consider made heroes of the suffrage prisoners, held themselves to be political prisoners? Do you ceremonies in their honor, and presented them agree with their claim? with commemorative pins. -

'I Want to Go to Jail': the Woman's Party

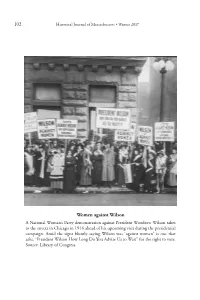

102 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 Women against Wilson A National Woman’s Party demonstration against President Woodrow Wilson takes to the streets in Chicago in 1916 ahead of his upcoming visit during the presidential campaign. Amid the signs bluntly saying Wilson was “against women” is one that asks, “President Wilson How Long Do You Advise Us to Wait” for the right to vote. Source: Library of Congress. 103 “I Want to Go to Jail”: The Woman’s Party Reception for President Wilson in Boston, 1919 JAMES J. KENNEALLY Abstract: Agitation by the National Woman’s Party (NWP) was but one of several factors leading to the successful passage of the Nineteenth Amendment and woman suffrage. By turning to direct action, concentrating on a federal amendment, and courting jail sentences (unlike the more restrained National American Woman Suffrage Association), they obtained maximum publicity for their cause even when, as in Boston, their demonstration had little direct bearing on enfranchisement. Although historians have amply documented the NWP’s vigils and arrests before the White House, the history of the Massachusetts chapter of the NWP and the story of their demonstrations in Boston in 1919 has been mostly overlooked. This article gives these pioneering suffragists their recognition. Nationally, the only women to serve jail sentences on behalf of suffrage were the 168 activists arrested in the District of Columbia and the sixteen women arrested in Boston. Dr. James J. Kenneally, a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 45 (1), Winter 2017 © Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State University 104 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 the Martin Institute at Stonehill College, has written extensively on women’s history.1 * * * * * * * Alice Paul (1885–1977) and Lucy Burns (1879–1966) met in jail in 1909 in England. -

Tbivision.Com October/November 2018

Formats TBIvision.com October/November 2018 MIPCOM Stand No: P3.C10 @all3media_int all3mediainternational.com FormatspOFC OctNov18.indd 1 01/10/2018 20:27 The original and best adventure reality format Produced in more than 40 countries 37 seasons in the US Production hubs available FormatspIFC Banijay Survivor OctNov18.indd 1 02/10/2018 10:42 CONTENTS INSIDE THIS ISSUE 6 8 14 This issue 6 Beat the Internet with Vice 14 TV’s love affair Kaltrina Bylykbashi visits the set for Vice Studios and UKTV’s Beat the ITV Studios Global Creative Network MD, Mike Beale, speaks to TBI Internet, a new play-along game show about Love Island’s international success 8 Hot picks Regulars TBI looks at some of the hottest upcoming unscripted titles. From Evil 4. People A round up of the latest movers and shakers in international TV Monkeys to finding The Greatest Dancer, there’s something for everyone 16. Last Word: Endemol Shine Group’s Lisa Perrin in our top list Editor Manori Ravindran • [email protected] • manori_r Television Business International (USPS 003-807) is published bi-monthly (Jan, Mar, Apr, Jun, Aug and Oct) by Informa Telecoms Media, Maple House, 149 Tottenham Court Road, London, W1T 7AD, United Managing editor Kaltrina Bylykbashi • [email protected] • @bylkbashi Kingdom. The 2006 US Institutional subscription price is $255. Airfreight and mailing in the USA by Sales manager Michael Callan • [email protected] Agent named Air Business, C/O Priority Airfreight NY Ltd, 147-29 182nd Street, Jamaica, NY11413. Periodical postage paid at Jamaica NY 11431. -

The Fifteenth Star: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party in Minnesota

The Fifteenth Star Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party in Minnesota J. D. Zahniser n June 3, 1915, Alice Paul hur- Oriedly wrote her Washington headquarters from the home of Jane Bliss Potter, 2849 Irving Avenue South, Minneapolis: “Have had con- ferences with nearly every Suffragist who has ever been heard of . in Minnesota. Have conferences tomor- row with two Presidents of Suffrage clubs. I do not know how it will come out.”1 Alice Paul came to Minnesota in 1915 after Potter sought her help in organizing a Minnesota chapter of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU). The CU was a new- comer on the national suffrage scene, founded by Paul in 1913. She focused on winning a woman suffrage amend- ment to the US Constitution. Paul, a compelling— even messianic— personality, riveted attention on a constitutional amendment long Alice Paul, 1915. before most observers considered it viable; she also practiced more frage Association (MWSA), had ear- she would not do. I have spent some assertive tactics than most American lier declined to approve a Minnesota hours with her.”3 suffragists thought wise.2 CU chapter; MWSA president Clara After Paul’s visit, Ueland and the Indeed, the notion of Paul coming Ueland had personally written Paul to MWSA decided to work cooperatively to town apparently raised suffrage discourage a visit. Nonetheless, once with the Minnesota CU; their collabo- hackles in the Twin Cities. Paul wrote Paul arrived in town, she reported ration would prove a marked contrast from Minneapolis that the executive that Ueland “has been very kind and to the national scene.